It is the responsibility of free men to trust and celebrate what is constant—birth, struggle, and death are constant, and so is love, though we may not always think so—and to apprehend the nature of change, to be able and willing to change. I speak of change not on the surface but in the depths—change in the sense of renewal. But renewal becomes impossible if one supposes things to be constant which are not—safety for example, or money, or power. One clings then to chimeras, by which one can only be betrayed, and the entire hope—the entire possibility—of freedom disappears.

—James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

A

After a decade living in North Carolina, I recently returned to live in London. My wife and I moved back into the same house we had left ten years beforehand when our children were, well, still children. The house and neighbourhood felt both intimately familiar and yet strange. Everything had changed. Nothing had changed. I felt caught between a world I knew and one I must learn again, as if from scratch. This experience pressed home for me the question of how to make sense of change.

Change is strange. It is always upon us, yet it is ungraspable. Periods of stasis can birth profound transformation, while revolution can reproduce the status quo. Moral and political change are particularly strange. Responses to them are the sites of some of our most polarizing and bitterly contested social fissures. Changing approaches to gender and sexuality are but one example of how change invokes strong reactions. Arguably, attitudes to change are the fault line shaping the contemporary culture wars. Is the answer to resist change and return to a previous era, thereby making America great again? Or is the only way to go forward, leaving behind the past so that society can progress?

As the quote from James Baldwin makes clear, any meaningful change, change that generates moral and political renewal, involves a movement from the world as it is to the world as it should be. Conversion is another term for this kind of change, one that has ancient roots.

In classical philosophies conversion tended to take two forms. On the one hand, there was a turning back to, a discovery or recollection of one’s true self lost or marred because of poor formation or living in a bad society. A modern literary example is the famous “Proustian moment” when the narrator tastes the madeleine and thereby recollects his true self and identity through going back in time to a more innocent and authentic version of himself. The structural analogue of personal conversion is revival, regeneration, or renaissance: the recovery or rediscovery of what was lost or corrupted through the return to an earlier, purer form of political order, institution, or practice. The temporal shift envisaged is backward (e.g., to a golden age), while the spatial shift is a return to either an older and better place (e.g., an Eden or Arcadia) or the repair of an existing place (e.g., re-wilding an industrial farm).

On the other hand, conversion could also be envisioned as a turning away from what is and was in order to begin anew. It involves a fundamental reorientation of one’s self. A classical parable of this kind of conversion is Plato’s cave: one leaves behind a realm of shadows and unreality through ascension to a new place or level so one can see what is really going on and live life more truly. To put it another way: I am awakened to enlightenment. Drawing on Marx’s ideas about waking up from false consciousness, the contemporary use of the term “woke” deploys a parallel idea of conversion. The structural analogue of personal conversion understood in these terms is revolution: the refounding of society, a radical rupture with the past, and a movement into a new, better, or more enlightened form of a political order. The temporal shift envisaged is forward (e.g., to become modern rather than medieval), while the spatial shift is to a different place (e.g., from England to New England). There is also a shift of vision, often marked by language of a transition from darkness to light (e.g., from the Dark Ages to the Age of Enlightenment).

Conversion, understood theologically, incorporates both these dynamics. The Old Testament understanding of conversion denotes not only a turn back or return to something but also a change of heart or consciousness—for example, the prophets calling the people to return to covenantal faithfulness as a way of going forward in their relationship with God. The same is true in the New Testament, which builds on this understanding. There conversion means to turn around, whether that indicates a turn back, a turn away from, a turn toward something new, or a change of course. Exemplified in the notion of repentance, this can also refer to a change of mind, consciousness, or way of being in the world. All these facets of conversion are captured in the various motifs for conversion strewn throughout the New Testament: a change from fruitlessness to fruitfulness, blindness to sight, lost to found, darkness to light, sick to healed, and being born again and becoming a new creation. These combine a sense of either recovery or rectification with a transformational sense of both newness and fullness.

Baptism is a practice that enacts the paradoxical movement of conversion described in Scripture: I discover and fulfill my true or authentic self—who I am created to be—through being born again. My old self is not abolished in the process of being born again. Rather, the true self is restored at the point of new birth. The paradox works in the other direction as well: starting anew involves recovering what was lost and is now found. Baptism points to how conversion is simultaneously retrospective and prospective. It entails a turn back, a turn away from, and a turn toward something—all at once.

When conversion is understood as not simply personal but also political, a theology of conversion contrasts sharply with both reactionary and progressive ideas of change. Reactionary and fascistic politics are often fuelled by a resistance to change and the desire to recover an imagined past that is envisioned as lost or stolen. Such movements fetishize the past and seek to reconnect with an illusory point of origin before things went bad. This kind of politics takes something good—namely, a desire to honour the traditions and customs that birthed and nurtured us—and turns it into something evil by absolutizing it and then sacrificing everyone else on its altar. A Christian theology of conversion points to how a healthy body and a healthy body politic involve a dynamic interplay between homeostasis and morphogenesis—that is, between continuity and the ability to keep things steady, on the one hand, and the ability to grow, change shape, and adapt, on the other.

When conversion is understood as not simply personal but also political, a theology of conversion contrasts sharply with both reactionary and progressive ideas of change.

The poet and theologian Samuel Taylor Coleridge puts it well. Abhorring alike the Jacobin revolutionaries and anti-Jacobin reactionaries of his day, Coleridge held that a humane culture must have an interplay between “permanence,” the tending to our inherited customs and traditions, and “progression,” innovation and development of new approaches. Coleridge was alive to how we are always caught between continuity and change. To survive let alone thrive as frail and fallen, time-bound creatures requires the careful cultivation of shared forms of life that can adapt and innovate as well as conserve and tend.

A theology of conversion also challenges all forms of progressive politics. Progressive ideologies depend on a particular conversion narrative. Conceptions of progress tell a story about throwing off our old, irrational selves, the foul accretions of religious superstition, and the dead end of tradition so we can become rational, autonomous, and enlightened selves able to enter into emancipated ways of life. Following this narrative, progressives see the past in Oedipal terms: it is a rival that must be killed or left behind in order for us to grow up and become what we should be. Change for the better necessitates a competitive, destructive process that abolishes the present in the name of future bliss. By contrast, Christian conversion looks to the transfiguration of the old, however weak, painful, or horrific, as part of the formation of the new: even crucifixion can be redeemed through resurrection.

Against both reactionary and progressive ideologies shaping the contemporary culture wars, a theology of conversion points to how meaningful change for the better always involves recovery and rupture, renewal and revolution. More often than not, those who claim to be revolutionaries are simply repeating the mistakes of the past in a different guise. Conversely, reactionary politicians, in the name of defending family, faith, and flag, enact top-down programs of social engineering that destroy rather than conserve existing forms of life. To echo Coleridge, a humane society requires the interplay of permanence and progression. To echo Baldwin, this involves a difficult struggle in which we trust ourselves to what is constant, to what really matters, to what has eternal value, while giving up attempts to secure ourselves and our way of life through relying on what does not—namely, money, status, power. Scripture points to how the only means for securing a way of life that endures for eternity is through the quality and character of our relationships with God and neighbour and the extent to which these are loving, faithful, and hopeful.

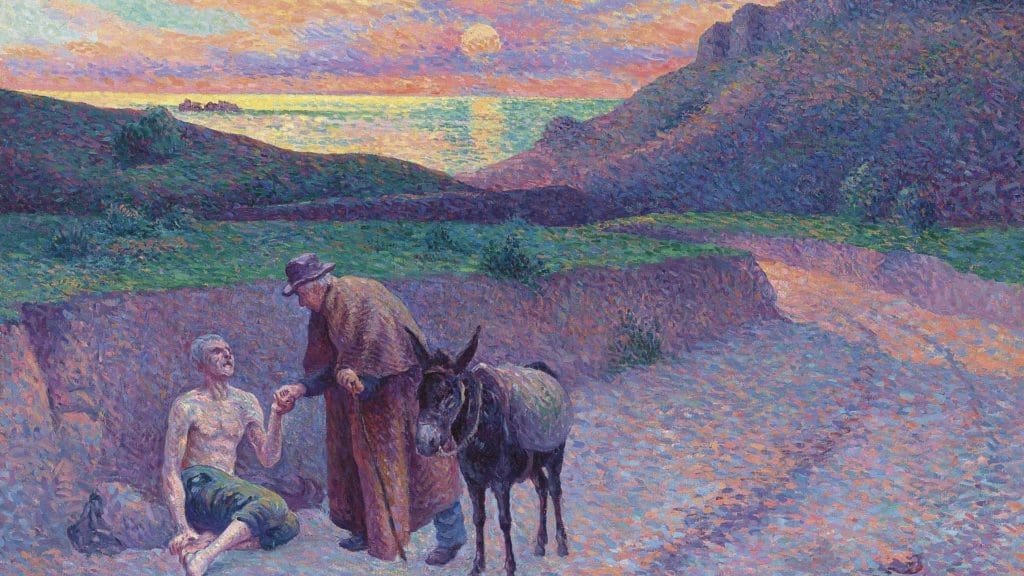

The conversion of St. Paul is emblematic of a theological vision of meaningful change, change that renews us and frees us in the depth of our being. When we meet Paul, he is Saul: someone raising himself up by persecuting others. On the road to Damascus Saul is knocked down. In Caravaggio’s famous portrayal of this conversion, Saul is thrown off a horse. There is no horse in the story as narrated in Acts. However, Caravaggio captures something important about Saul’s descent. The horse symbolizes Saul’s reliance on state power and the markers of elite status to gain standing and prestige. As New Testament scholar Brittany Wilson contends, to become Paul he must be unmanned and go through a process of being stripped of his power.

Christian conversion looks to the transfiguration of the old, however weak, painful, or horrific, as part of the formation of the new: even crucifixion can be redeemed through resurrection.

He is blinded. Such disablement is a sign of stigma. He must be led by Ananias and so lacks self-mastery, which is a source of shame. He loses command of the soldiers and fails in his mission and so lacks military honour. He must receive from and be cared for by others and so is a client rather than a patron, which is to be without political power in the Greco-Roman world. Subsequent to his conversion we learn that he cannot rely on rhetoric to win followers. And finally, he is not a father and is celibate and so lacks virility and has no human future as he has no children to carry on his name. Thus Paul’s conversion transforms not only him but also his relationship to the principalities and powers of his age. He cannot rely on worldly ways and means to achieve what needs to be done or to gain recognition and status. Quite the reverse, the means of earthly power become instruments of his own persecution.

Paul’s conversion does not, however, lead him to transcend the world. The journey he goes on after his conversion is no ladder of ascent. Rather, how he remembers, imagines, desires, and relates to the world around him is transformed so that he is enmeshed within it more fully. He ceases to be a zealot able to watch impassively while another is stoned to death and consider this a just and righteous act. Instead, he is saddled with care and becomes one who is prepared to suffer extreme hardship for the sake of others. His letters are suffused with compassion, tenderness, frustration, and anxiety for those he loves. He endures shipwreck, imprisonment, and repeated beatings for people he names and communities he has lived with. His conversion renders him vulnerable to the risks, tragedies, betrayals, and joys of finite and fallen relationships. Conversion thereby renders him more human.

This is the mark of true Christian conversion, our metric by which to measure change: Does change render us capable of bearing each other’s burdens? Does it render us more humane? Change that alienates and divides us is not change that renews and liberates. Neither is change that places all the burden on some so that others might be unburdened and so live lives of careless unconcern.

The political theology of conversion is summarized by the call of Jesus in Matthew 13 to be salt and light. As salt we identify and conserve what is good in our society that we receive from those who came before us, tending and cultivating it so that it can be handed on to the next generation. As light we expose the deeds of darkness and bring understanding. Being light means identifying what needs changing if we are to move from the world as it is to a more generous and just one.