R

Rosina, a young Canadian woman, called Health Canada in September 2020 to inquire about receiving euthanasia treatment to end her mental and physical suffering. On the call, the nurse assessing her case assured her, “I just wanted to reassure you that, with MAID, it is a very dignified death. There’s nothing embarrassing about it, you don’t lose control of your bowels; it’s a very elegant, graceful, dignified death.” Rosina had earlier cautioned her lawyer against revealing to Health Canada the true reason she wished to die—loneliness. While the official reason she qualified for euthanasia was her chronic physical pain, she admitted to her YouTube audience of thirty-six subscribers that “sometimes the pain will all go away by having another person there.” Rosina’s application for a euthanized death was ultimately successful. She died in her home on September 25, 2021, a date purposely chosen for its being the birthday of her ex-husband.

Euthanasia became legal for the first time in Canada in 2016. It was initially permitted only to those with terminal illnesses in order to help them control the “variables” of their death. In March 2021, however, Bill C-7 expanded euthanasia eligibility to those with chronic illness and various disabilities, no longer requiring an impending inevitable death. This move, presented as the simple “expansion” of eligibility for a viable, existing program, was in fact, philosophically, a seismic shift. No longer was euthanasia a quicker end to a battle that death had already won; rather, it surreptitiously merged with other forms of viable health care, becoming one option among many for the alleviation of suffering. In March 2024, eligibility for euthanasia, or medical assistance in dying (MAID), as it is officially designated in Canada, will be extended to those who experience mental illness.

Euthanasia’s rapid trajectory of all-inclusive accessibility on paper is exceeded only by its accessibility in reality. Euthanasia has gathered for itself a wide web of “patients,” many of whom have received it despite technically failing to meet its “rigid” eligibility criteria. In 2019, Alan Nichols of Chilliwack, British Columbia, successfully qualified for MAID on account of one medical condition alone: hearing loss. What this means, in effect, is that Nichols was able to find two doctors or nurses to sign off on his claim that his hearing loss proved a “grievous and irremediable medical condition.” The subjective “compassion” of those two health-care workers allowed his application to jump through the government’s already loose hoops. In British Columbia, dozens of doctors in recent years have specialized in “euthanasia care,” effectively forming a “compassionate” network of euthanasia-friendly doctors, prompting a frenzy of suicide tourism within Canada.

Canada’s ostensible commitment to preserve the life and well-being of its citizens is currently locked in an ideological battle. Section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms states that “each person has the right to equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination.” If we restrict euthanasia to some categories of persons who do not qualify on the basis of the condition of their body alone, are we not discriminating against their autonomous access to the “equal benefit” of the law? This claim is not to make a farce of the situation, nor is it hypothetical. Stefanie Green, the president of the Canadian Association of MAID Assessors and Providers (who herself has carried out over four hundred MAID procedures), recently expressed concern that preventing access to euthanasia because of a person’s “inability to have a specific diagnosis” is inherently discriminatory and unconstitutional.

Canada treads along with its modus operandi of “agreeing to disagree,” tethered together by a dubious mixture of socialized goods and individual autonomy. This fragile ideological framework is revealing itself for what it is, as it almost laughably attempts to balance, on one hand, socialized health care in service of life and health and, on the other, individual autonomy that demands a right to death. Depending on your particular mood or moral quandary, you may choose to call the 1-800 suicide hotline to have a good-willed government worker talk you out of taking your own life, or, rather, you may wish to call the other 1-800 Health Canada number to learn more about receiving a “death with dignity.” In a recent CBC article, one woman living with anorexia claimed that if the government does not allow her access to euthanasia soon, she might resort to “killing herself.” Because euthanasia successfully gets away with being considered a health-care option (an equally respectable alternative to palliative care or cancer treatment, for example), it is no surprise that Canada has become a leader in the world of “death care.”

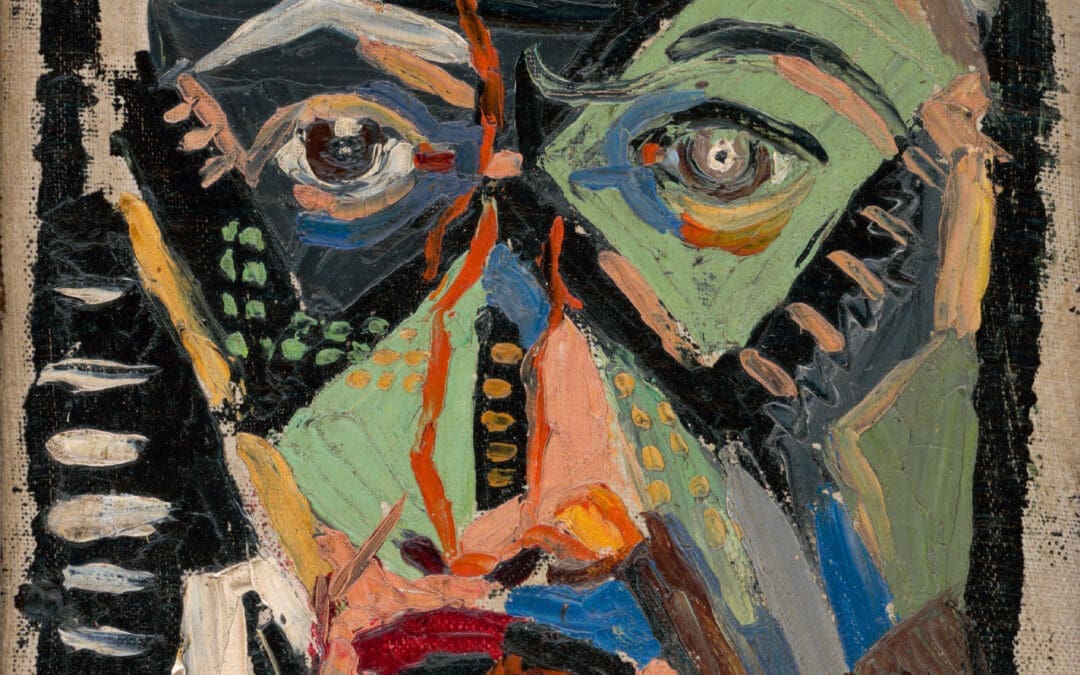

Public discourse propagandizing euthanasia often focuses on the “dignity” of the life that precedes its death. As Rosina was told on the phone, a person who chooses euthanasia is saved from the disgust of physical suffering—loose bowels, hair loss, or other forms of bodily decay. A beautiful death has become a death that is free of suffering and bodily disgust and decay. A publicly acceptable health choice is to allow one’s body its full health until it begins to decay. Rarely does one hear about what happens after euthanasia—namely, the death of the body. This takes place out of the public eye; the death itself is unseen. After the healthy body’s death, it is, at least publicly, unthought. What remains is simply a memory of a dignified healthy body prior to its ruptured end. A healthy, full, vibrant life, and then a chasmic end. A Princess Diana effect, so to speak.

Death has quietly yet abruptly receded from our field of view. What we are left with is a field of life that is abstracted from the wider truth of finitude and transience.

The Orthodox theologian Fr. John Behr speaks of how, for many decades now, we have been pushing death out of our sight with new habits of hospitalization, cremation, and so on. We don’t “see” death the way we used to. Rather, death has quietly yet abruptly receded from our field of view. What we are left with is a field of life that is abstracted from the wider truth of finitude and transience. Our public and ecclesial “liturgies” around death (the funeral, the visitation) have already declined in public practice. More common now is a simple “memorial” service, where guests, saved from having to look at the lifeless body, often instead view a slideshow of the deceased person in the glow of life. Perhaps now, with euthanasia, yet another “liturgical” step is being offered its more sanitary alternative. No longer does the dying person have to experience their decay, and no longer is the community obliged to care for, or even consider, the dying body.

In some ways an unlikely figure, Judith Butler is helpful in diagnosing the philosophical matter at hand. Butler suggests that our ways of seeing or apprehending others—our “frames” of view, so to speak—are politically saturated. This political saturation is not simply figurative. The political is forcefully active as it energetically can both expand and delimit life’s “conditions of appearance.” In lay terms, the political plays an active role in how the public sees life, and what that life looks like. Euthanasia offers a beautiful and sanitary death, a death that is saved from the horrors of bodily disgust and suffering. This raises the question, When a beautiful and socially condoned death is characterized as the eradication of disgust and suffering, what is (softly) being implied about the proper conditions for life? The political will continually attempt to make ontological claims about the proper conditions for, and limits of, a “good” life.

In the introduction to Frames of War, Butler makes a cautionary remark regarding the death grip that the political supposedly holds on the public’s perception of ontological matters: “If a life is produced according to the norms by which life is recognized, this implies neither that everything about a life is produced according to such norms nor must we reject the idea that there is a remainder of ‘life’—suspended and spectral—that limns and haunts every normative instance of life.” When we, essentially, define life as godlike by ending it swiftly as soon as signs of limit or decay approach, we forget all too quickly that there will necessarily be a “remainder” haunting our preferred normative instance of life. We cannot actually remove death from life, and if we try to do so, death will grow into a figure of its own—a haunted, suffering, and grotesque figure. For Butler, this is not just theory. If we make death a figure of its own by prying it out of our notion of life, then we will also invariably force specific persons or groups to inhabit and enliven that haunting figure of death. In other words, the underbelly of our utopic and godlike normative life is a spectral figure of death that needs to be realized by real people. Disability advocates have, for several years now, warned about the immense setback in public perception that will be suffered by those with disabilities when euthanasia is freely offered to all of them.

Death is not simply life’s end; it already exists within life itself. Further, life’s relation to death is meaningful. This insight pertaining to what it means to be human can be traced all the way back to Homer’s Odyssey. Odysseus leaves his nymph-lover Calypso, and her promise of his immortality, preferring to face battles, perils, and death in order to return to his wife Penelope. When euthanasia is offered, death is offered as an alternative to life—a fork in the road. If life is viewed as increasingly impervious to and separate from death, then an ideological justification for euthanasia will gain more traction. What is necessary is a recognition of life and death as one paradoxical union within a beautiful life itself.

Death is not simply life’s end; it already exists within life itself.

The Canadian health-care system is, for good reason, currently under attack for allowing those who want to die for “bad reasons” to slip through its greasy safeguards. For example, there have been numerous recently exposed instances of people receiving euthanasia to “cure” themselves of their financial poverty. Luckily, choosing to die because of poverty is still considered a “bad reason” to choose euthanasia. But in many cases (as evidenced by euthanasia’s 34 percent growth rate in Canada from 2020 to 2021) people are choosing to die despite, at least on paper, having their social needs met. Butler helpfully offers us complex diagnostics of our ontology-claiming political machinery, but the limit of the theory is that it assumes a postulated internal drive to live. What simply doesn’t make sense within Butler’s system is the instance of a person choosing to die when her social and political conditions for existence are met. And in more and more euthanasia cases, this is exactly what’s happening. Perhaps there is a tenuous “remainder” that is extraneous to Butler’s attempted ontological framework itself: a remainder of people who will choose to die with no “good” reason at all.

This points us toward the recognition of the true seismic shift occurring with the expansion of euthanasia. Death is not only condoned but even sometimes encouraged, despite the fact that, in many of the cases of those who choose euthanasia, their needs are being met by their political system. Canada won’t be able to navigate this ideological paradox forever. As euthanasia inevitably loosens its restraints on who can exercise the “right” to a dignified death, the margins for the public acceptability of a decaying life will be, at least implicitly, narrowed. If death itself were not constitutive of life, and a meaningful and beautiful life at that, then ultimately we’d all be better off one day taking a final whiskey-and-pentobarbital nightcap.