I

In the final chapter of Francis Spufford’s novel Light Perpetual, one of the central characters approaches the end of his life under hospice care. The spiral of his thoughts brings him to this question: “Mightn’t there be a line of sight, not ours, from which the seeming cloud of debris of our days, no more in order than (say) the shredded particles riding the wavefront of an explosion, prove to align?”

The whole novel, leading up to this moment, constitutes an answer to this question. There is indeed a “line of sight, not ours.” There is a meaning to the world beyond the “shredded particles” of our moments and our days and someone, not us, who sees. And the final paragraphs give an appropriate response to that truth: praise. The last conscious thoughts of this character are the words of Psalm 150: “Let everything that has breath, give praise.”

Light Perpetual is saturated with religious significance but has been curiously overlooked by Christian readers otherwise eager to champion novels of faith and redemption. While Marilynne Robinson was justly lauded for writing the first great novel of faith of the twenty-first century, Spufford has received little attention in religious circles. I talk to a lot of Christians about the fiction they are reading, and none has ever mentioned Spufford’s novel. Perhaps this is because Spufford is British rather than American, but it’s not because he’s an obscure writer. He has a well-earned reputation for high-quality nonfiction, and his debut novel, Golden Hill, won several literary awards. Light Perpetual itself was reviewed in venues like the New York Times Book Review and the Times Literary Supplement. It is not for lack of exposure, then, that his novel has been overlooked by his fellow Christians.

Whatever the reasons for its neglect, Light Perpetual continues a century of Christian fiction depicting redemption in subtle, unconventional ways. Spufford’s novel belongs to a lineage including Graham Greene’s whiskey priest in The Power and the Glory, Evelyn Waugh’s decadent Oxonians feeling the tug of faith in Brideshead Revisited, and Muriel Spark’s surprising representation of martyrdom in postwar London in The Girls of Slender Means. Light Perpetual is, I would argue, as beautifully written and thoroughly grounded in Christian theology as any of these books and deserves to be read as the direct successor to this literary tradition.

The novel begins with five children standing in a Woolworth’s department store in Bexford, an imagined borough of Southeast London, in 1944. (A note on the perils of writing about a novel that one hopes one’s own readers will eventually try: In what follows, I talk about many of the events in the novel, but to preserve the sense of unfolding mystery in each character’s story, I will not give their names.) Before the end of the first chapter, the children, their mothers, and all others within a few blocks of the store are obliterated by a V-2 rocket. The narrator describes the bombing in piercing, technical detail: “The moving thread of combustion, all combustion done, becomes a blast wave pushing on and out in the same directions, driven by the pressure of the livid gas behind. And what it touches, it breaks. A spasm of deformation, of dislocation, passes through every solid thing, shattering it to fragments that then accelerate outward themselves at the forefront of the wave.”

And then, in the conceit that motivates the rest of the story, the novel imagines that the children were not killed, that the rocket “flew four hundred yards further . . . and killed nothing but pigeons” or fell into the North Sea or failed to launch at all. The five children are redeemed from destruction and given the gift of life. The novel then begins again, with an invocation of grace: “Come, other future. Come, mercy not manifest in time; come knowledge not obtainable in time. Come, other chances.”

There are many chances for the five children. The novel visits these characters whom it has restored to life as schoolchildren in 1949, in their twenties in 1964, on the cusp of middle age in 1979, in their fifties in 1994, and one last time in 2009.

For a novel that grants so much mercy at the start, Light Perpetual is merciless in its depiction of these five lives. None is charmed.

One character builds a career as a typesetter in the printing industry only to see his trade collapse with the advent of personal computers and digital printing. Another participates, too briefly, in the rock music scene of Los Angeles as a musical collaborator and sometime lover to a star musician who never gives her credit for her talents or contributions. A character ends up in prison as an accessory to a hate crime. Another suffers from schizophrenia. The last of the children participates in the spectacular ups and downs of the London real estate market, all the while exploiting others for his advantage.

If the trajectory of this novel passes through much cruelty, its arc bends toward mercy.

It gets worse. Light Perpetual unflinchingly describes an act of coerced oral sex, the heartless calculations of a scammer, the clinical and bureaucratic abstractions of institutionalized mental health care, and the torment and chaos of de-institutionalized mental health care. A Pakistani man is brutally beaten and murdered in a parking garage by a group of neo-Nazi skinheads. Even the more quotidian hurts of its characters are described with unsparing realism: a father who doesn’t know how to talk to his teenage son; jealousy between sisters, one of whom can conceive a child and one of whom cannot; a couple who drift away from their shared commitment as they develop new interests in middle age; a man who helplessly watches his granddaughter waste away from an eating disorder.

And for all this, grace is never spent. If the trajectory of this novel passes through much cruelty, its arc bends toward mercy. These characters, who live in a world of so much brokenness, also live in a world suffused with unearned mercy. Just as their lives were spared at the beginning of their stories, so they are offered grace upon grace.

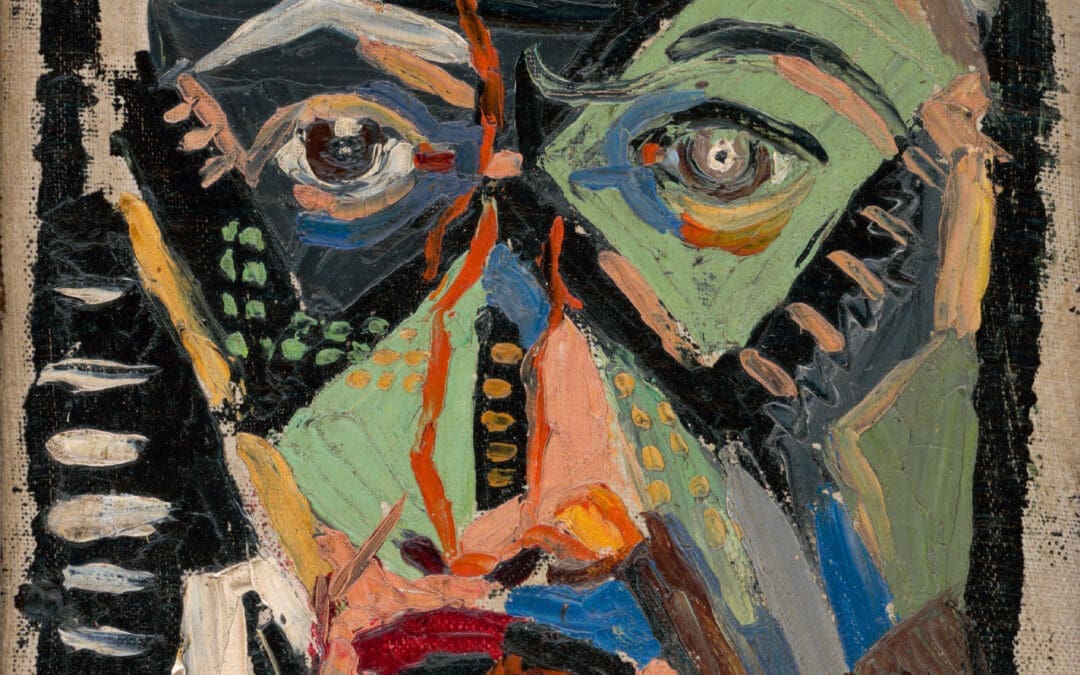

Grace comes through music. In an early scene, the children are all together in a primary-school music class, singing “The Ballad of the London River.” The character who will go on to become a professional musician experiences the music as image and colour: she can “hear the idea of the ripples coming firm and clear through the plinking of the old upright, saying: here is the river, here is the river, and making spreading rings of green and bronze in her head.” As an old woman facing the imminent death of her husband, she listens to a tape of a song she recorded years before and hears in it both gratitude and sorrow: “It is the song of missing what you still possess; what, for a little while longer, you have and hold, but must presently relinquish to the dark.”

Another character secretly loves opera. On multiple occasions, an encounter with this music almost—though never quite—tugs him away from an act of selfish cruelty. As he’s about to make a dishonest business deal, he sees across a restaurant an opera diva whom he adores, and for a moment he is so overwhelmed with her that he is forced to confront his divided will: “Out of the chrysalis of the usual him has crept this damp-winged other [man], who only wants to stare. . . . Who doesn’t want to speak the lines insisted upon by the plausible fat man in the blue suit. Who almost resents him, in fact, with his grubby little scheme.” Later in the novel, at the height of his wealth and success, he sits listening to Cherubino in The Marriage of Figaro and feels the emptiness of his life: “So what can be wrong, he thinks angrily. . . . He is rich. . . . He can afford to buy himself any pleasure. He is surrounded by delicacies, none forbidden. Death is still far away (surely). Yet something makes him ache. Something coming from the stage.” The answer comes in the words of the opera: “I see a blessing outside myself, / from whom I don’t know, or what it even is.” The grace in music offers the provocation to make a better choice, a prompting to look beyond oneself.

Grace also works through proximity. As these characters grow up in the same neighbourhood and then move out into the broader world, they are drawn back repeatedly through family and economic ties. A coincidental meeting on a rainy morning sets the stage for one character to offer another a cup of tea, and then something stronger, upon learning that the second man’s marriage has just collapsed. Two of the characters recognize each other on a bus—one a passenger, one a conductor—in a tense moment when a sympathetic intervening word can prevent an act of violence. The novel is a hymn of praise to a city packed with humanity and a neighbourhood where old school fellows serendipitously meet.

The long timeline of the novel gives space for the grace of second chances. Two of the characters face dead-ends in careers for which they seemed ideally suited in their youth. Both of these characters end up connected to secondary education: one becomes a principal who uses his negotiating skills to get better funding for his school; the other uses her musical gifts to usher her students into the beauty of making music.

In a dynamic world permeated by the providential grace of God, opportunities for beauty and redemption can arise even after failure.

These are seemingly ordinary occurrences. But in a dynamic world permeated by the providential grace of God, opportunities for beauty and redemption can arise even after failure. Grace also comes by what might seem like a more obvious route, though it has now become neglected: by people of faith acting out their commitments.

In one case, a bus driver stands up to a gangster. He is a six-foot-three heavyweight champion and a deacon in the Joyful Assemblies of the Holy Spirit who “doesn’t feel he is under the obligation to spell out his commitment to the path of heavenly peace in situations where the greater good would be served by keeping shtum.” He intervenes to protect his conductor.

In another case, a clergyman working all night at a crisis hotline ministers to the character who was an accessory to murder and invites her to go to church. He says, “I know I don’t talk about God much, but one of the things He’s very good for is confession . . . and it sounds like you’ve been carrying some hard, hard stuff for a long time. And I wondered if I could tempt you to come and join us on Sunday morning, and see if that might help?”

The character who suffers from schizophrenia finds grace in modern medicine, in a happy marriage, and through the ministry of a charismatic pastor who casts out an evil spirit and preaches the gospel. In one Sunday sermon, in his Nigerian lilt, the pastor compares London to Jerusalem. “It had nightclubs. It had bad areas. It had dealers in wickedness,” he says, and argues that God loved Jerusalem like he loves London: “Did he want to burn it? To wash it away in a mighty flood? No. No. He went another way to clean up that dirty place. He love it. He want to redeem it. And he did redeem it. He wash it with his blood. He wash it bright and clean. He make it new. The New Jerusalem, brothers and sisters, beautiful like a bride; think of that.”

Grace comes in many ways. Spufford’s willingness to depict pastors, deacons, and ordinary people of faith not as dupes or hypocrites or moral monsters but as the emissaries of grace is surprisingly compelling.

Why, then, with these themes, has this novel not been widely read by Christians?

Spufford is a Christian and, as an adult convert, wrote a refreshing defence of faith titled Unapologetic: Why, Despite Everything, Christianity Can Still Make Surprising Emotional Sense. He attempts in that book to give fresh expression to old truths, most memorably in his definition of sin as “the human propensity to f[—] things up.”

Admittedly, Spufford’s propensity to drop the f-word in his writing might make his novel an awkward choice for some church-based reading groups; Light Perpetual will not likely be included on any Christian homeschool literature curriculum anytime soon. Robinson’s Gilead, told from the perspective of an aging congregational minister, is a much easier sell for a range of audiences.

But the choice to look frankly at life in London in the late twentieth century is also a choice to write about the world as many people experience it, a world where explicit religious observance is absent from most people’s lives and sex and violence are very much present. The vicar of the church I attend when in London regularly reminds his congregation that less than 5 percent of people in London go to church. The major British Christian writers of the twentieth century—Greene, Waugh, Spark—were writing for a world in which Christianity, though rejected by many, was still part of the cultural milieu. When they write explicitly of sex, violence, and faith, it is the sex and violence that surprises. In Light Perpetual, it is faith that surprises.

When Greene and Waugh and Spark write explicitly of sex, violence, and faith, it is the sex and violence that surprises. In Light Perpetual, it is faith that surprises.

When I taught this novel recently to a group of Christian university students in a three-week study-abroad course in London, they immediately saw the relevance of the novel to the London they were experiencing as they navigated their way through parts of the city away from the major tourist attractions. Drug and gambling addictions, mental illness, drunkenness, and simmering violence are familiar sights in the crowds packing public transportation or spilling out from pubs on a weekend night.

My students understood that this is a realistic novel about contemporary London. But they also, especially in the early chapters, missed the theological thread running through the plot. They saw only the realistic depiction of brokenness—a common feature of contemporary literary fiction. What they were not prepared for was a novel woven with cross-threads of transcendent meaning. They were surprised by grace. For readers longing for transcendence in fiction—both in the sense of exceptional craft and in the sense of addressing a reality beyond this world—this novel is indeed a surprise, a gift, even a form of grace.