Several years ago, I began my work as an arts administrator in New York City, the art capital of the world. Because my prior knowledge of art history and the inner workings of the contemporary art market was as slim as my wallet, I accepted the job hoping I had the wherewithal and curiosity to “see” my way towards artistic sensibility and, more importantly, toward wisdom. With the future of a flourishing movement in mind, I focused on John Ruskin’s words: “The greatest thing a human soul ever does in this world is to see something and tell what it saw in a plain way. Hundreds of people can talk for one who can think, but thousands can think for one who can see. To see clearly is poetry, prophecy and religion, all in one.”

Living in NYC, a young gal has dozens of museums within walking distance of her apartment. I’ve formed habits—some fun, some constructive—for how I approach the near constant influx of exhibits, retrospectives, biennials, and temporary installations from the Museum Mile to Bushwick. Here’s the quick low down.

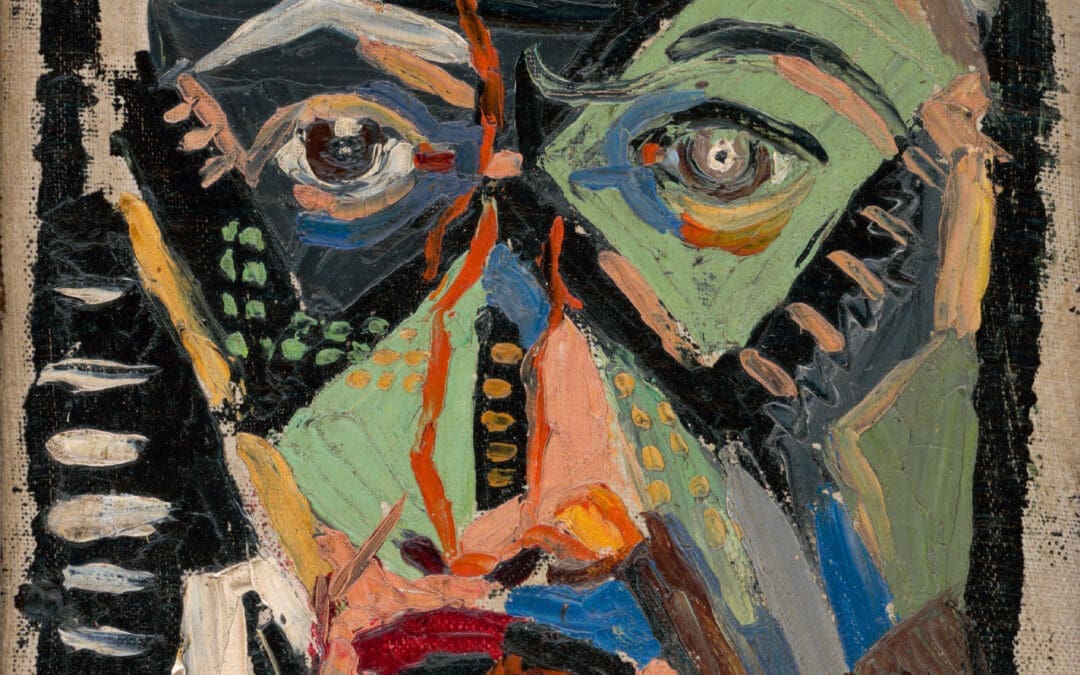

When they’re not having a Kandinsky show, I slide down the ramps of the Guggenheim Museum on Saturday evenings. It boasts some of modern art’s most important players, including Mondrian, Picasso, and Chagall. Frank Lloyd Wright’s legendary architecture educates as much as the art it houses. I occasionally take in small exhibits at the Morgan Library on my lunch break. This is where I’ve seen Degas’s drafts, Dylan’s lyric sheets, and multiple antique editions of Dickens’s Great Expectations. Walking into J.P. Morgan’s estate, I’m presented with a gift of historical art, wrapped by the one of America’s great economists, with his legacy of patronage the bow on top. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is the largest museum in the United States. I visit the Met with out-of-towners and then wander off to the archives, where my favourite work is kept. The MoMA, the United Nations of the art world, reminds me how central New York is to the international art scene. I try to visit the Whitney with at least one pal my side because their exhibits, more than any other, make me talk. The Biennial is the most conceptually diverse show I see all year; it’s like being seasoned by a whole spice cabinet of contemporary American art in one viewing. Major judgments are made as a result of the failure or success of the Biennial: gallery rosters, market prices, MFA programs weighed by the public. I wear my best outfits to the New Museum when I want to be reminded that I have the propensity to enjoy highly conceptual art, but my octogenarian sense of nostalgia hinders my comfort there. At the Neue Gallerie, which specializes in German and Austrian modern art, I hope to end my visit with a huge slice of chocolate cake from Café Sebarksy because I’m convinced Klimt would do the same. Chelsea’s galleries are always changing. You can change with them. I’ve resembled anything from a gawking bike messenger to a suede-wedge-wearing “gallerina.” Brooklyn is where our artist friends live and play and play and live and make work about living where they play and everything else under the East River sun. Phew. You gotta hustle.

Open New York Magazine, The New Yorker, or the New York Times, and you’ll find museum buzz—acquisitions, heists, galas, governing boards, and major purchases—as easily as flukes like the mayor’s ban on super-sized sodas or his Spanish lessons. In the midst of all of this coverage, what may not be so easily accessed to average readers are answers important questions in the life of these institutions: “Why display objects?” “How can we justify the collection, preservation, display, and elucidation of artifacts in the face of poverty?” “Should museums change with the times?” These questions are worth asking. And a reasoned answer doesn’t stop with merely justifying art as a common “good.”

The cave, the palace, and the temple each played their part in housing works of art for various purposes before the inception of the art museum. However, exhibiting art in service of the public good was a revolutionary ideal ushered in by the French after churches and palaces were ransacked during the French Revolution. As James Panero says, “The Louvre had new purposes, a self-conscious awareness of art as both a contemporary and a historic product, as well as the acceptance of responsibility for the public exposure of certain products as art.” If the idea of genius and high art is first properly associated in the West with the Renaissance, then the idea of the art museum was a somewhat belated product of the Enlightenment. Since then and until today, no one has seriously questioned a concept of the art museum in the definition adopted by the Association of Art Museum Directors: “A permanent, non-profit institution, essentially educational or aesthetic in purpose, with professional staff, which acquires objects, cares for them, interprets them, and exhibits them to the public on some regular schedule.”

The variety in the museums I listed above shows that in contemporary society art museums have different aims and serve different roles. Many assert that the primary function of art museums ought to be research and scholarship, staunch in their pursuit of objectivity, while others insist that it is about pluralism, the fortification of diversity in a pleased and intrigued public. There are institutions that, as the great critic and phrase-coiner Harold Rosenberg said, that “provide homes for aged masterpieces.” It’s also popular, even cliché, to think of them as the new church, a sanctuary, a place for meditation and solitude. And yet others like the City Museum in St. Louis pride themselves on their quotidian place in every day life, creating a lived, playful experience within the walls of the museum. Perhaps most simply of all, some see the museum as a place of protection, a neutral space, a safety net for art from outside forces that would seek to destroy it.

But the question that begs asking: “In pursuing any of these goals, should museums focus on exploring objects or investigating their contexts—are they about looking at things or telling stories?” For formalists one answer is held, for conceptualists another. While the relationship between the artist and society can be demonstrated to have had a determining influence on art style, studio practice remains largely personal. The painter invents forms in his own métier, giving definition to subjective experience. As Wittgenstein put it, much of the knowable universe is beyond “facts.” There are intuitions associated with “feeling” that one can say nothing about but that can be mysteriously experienced in the recognition of a brushstroke or the carve of a knife. In the same way a poet recites their rhyme to a room, a painter creating out of individual consciousness displays his work, and upon doing so animates a society by their response to it. A single painting can encompass a full range of subjective experience: concepts, emotions, senses, and moods. The catalytic conversation between maker and viewer is emboldened through the life of the museum, as are books in their libraries, and cures in their labs.

Art museum attendance in the United States is growing exponentially. In 1962, around 22 million people visited an art museum; by 2000 over 100 million did, with 850 million Americans visiting museums of all varieties each year. Paul DiMaggio, chairman of the sociology department at Princeton University and an expert on public participation in the arts has also noticed the attendance shift. “Art museums in the United States have really made it in the last 15 to 20 years. It is the only art form that has dramatically increased attendance of people of every kind, not just the intellectual elite. It is the great arts institution success story.” With this apparent surge in art appreciation, one must ask how the institutions have changed since their inception. Philiippe de Montebello, the former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, suggests this indicates that the museum founders’ original intent and mode of operation, personified by famous polymath patrons like J.P. Morgan, is being lost in the shuffle. From the same New Criterion piece linked above: “With yesterday’s art traded for today’s trend, exhibition halls taken over by ‘social space,’ and new buildings expanding around traditional facilities, museums are shedding their old skin and remaking themselves in our image. It is said that museums have gone from ‘being about something’ to being for somebody.” For those committed to the curatorial model established at the turn of the century, this shift is most obvious in the dissolution of a museum’s permanent collection. It was once thought that selling a piece from a permanent collection—whether it was purchased or entrusted to a museum—was like selling a child. Unquestionably, it was in poor taste, especially when done to acquire newer, less expensive works. Very often, permanent collections are assembled with pieces bequeathed by a patron, or they are works indicative of the region or era the museum specializes in. The National Gallery’s permanent collection, for instance, is thoroughly English, while its younger cousin down the street has taken a more nuanced international approach to gathering artwork. Among people working in the field there is a pervasive and lingering philosophical wrestling match between what was, what could be, and what ought to be.

But maybe there is room for both progression and a dignified praise of what’s passed. Can’t it simply be both? New York City’s museum mile can boast nearly a dozen museums all serving different ends. Can’t living artists install bamboo rollercoasters on the roof of the Met, while El Greco’s “View of Toledo” hangs below in all its glory? Perhaps it’s simple. Maybe, above all, the art museum can be what one Japanese museum builder called “a Pavilion of the Pure Pleasure of Art.” Museums are menageries assembled by a few for the whole. They are a family album of a heritage not our own. While being an archive of what’s in the past, they are a mirror for the present, and a glance at what is to come. They are for everyone who wants to “see” work by their kind, a chance to empathize with a maker.

A month ago when my mom came to visit me, I realized again that I am very much my mother’s daughter. My past and present came together rather unexpectedly as I stared at a Jasper Johns’ Flag I, a piece I was sure my mom would resonate with since it was reminiscent of Kirkland’s kitsch. The fascination in my mom’s eyes as we strolled the MoMA was enriching. When we settled at Alighiero Boetti’s exhibition on the sixth floor, she began grilling me and my friend Lindsay—a fine artist—with questions about process, materials, technique, and purpose. The reciprocity of that moment was thrilling to me: my mom’s genuine curiosity was met by Lindsay’s knowledge and expertise. Listening to them converse reminded me of the first time I saw the Pop Art of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein and wondered what the big deal was. My mom was experiencing an intuitive empathy she’d never had before. As it was my mom’s first time to the MoMA, we had to view the permanent collection to see archetypal pieces of modern art, beginning with the Impressionists. We journeyed up to the appropriate wing and at the centre, a crowd of onlookers were gathered around what was obviously “Starry Night.” I looked at my mom with raised eyebrows and a grin, biting my lower lip, a glance she knows well.

I said, “We’re here. There it is.”

She turned her back to me, looked around for a while and said, “Okaaaaaay, sooooo, are you going to show me Van Gogh, or what?” I was quickly reminded that her enthusiasm in the last room didn’t guarantee recognition of the artifacts in this room.

“Right there! Starry Night is right there. It’s the one kids are snapping Instagram photos of.”

She stares at it for a bit. I begin to realize that she’s missing something. We talk about what it means to be an impressionist. I encourage her to take a closer look at the application of the paint, to see how much of the palette Van Gogh utilized in just a square inch of space. She began to delight.

“Is it the only one?”

With true sincerity, Kristen (a MoMA employee) and Lindsay took a few minutes to bloviate on what made this artifact special, why it was there, and who Van Gogh was in the scheme of things. Kristen told my mom about the camaraderie between artists of similar periods, or from certain locations, and how their work is indicative of shared experience. We also began a lengthy discussion of how epochs in art history work, what sort of social changes push certain artists toward the avant-garde, eventually resulting in a paradigmatic shifts. In a few short moments, my mom for the first time ever, was able to view “Starry Night,” “Les Demoiselles de Avignon” by Picasso, and “The Red Studio” by Henri Matisse. I was surprised by the certain serendipity within those walls, and it wasn’t for reasons I thought it might be. It was a boogey feeling, and she didn’t feel exotic. She felt much like her daughter had when I first began to hone my museum-going techniques: perceptive. I’d never claim that these experiences define my “experience” of art. I’ve no liturgy for museum going, but I am ready to claim that these experiences have been tremendously catalytic in the formation of my perception. In “seeing” I am judging, feeling, intuiting.

That afternoon in the MoMA was, for my mom, the start of a new-found empathy, an understanding of particular artifacts, artists, and thankfully, what her daughter does for a living—something she felt uncomfortable with before. For me, it was a reminder of what an instrumental gift the archives at the MoMA and chocolate cake at the Neue Gallerie had become. When my mom and I exited the museum, I was mightily encouraged and sort of shocked. Her next question came and I was ready: “I want to take your dad to the museums in San Antonio. That was wonderful. But just one thing was missing. Why didn’t they have the Mona Lisa?” The journey will be long, but there are plenty of museums for us to explore together.