(To be read with Dandy Warhols’s “Bohemian Like You” playing in the background)

In our postmodern age, a lot of Christians are worried that truth is under fire. Unfortunately, I think they’re trucking water to the wrong blaze. This is because they’ve misdiagnosed the cause of the fire, construing the problem as a matter of knowledge. Following Augustine, I want to suggest that what’s at issue is a matter of love. And this isn’t just some Augustinian invention. In this respect, Augustine is faithful to the Apostle Paul.

Indeed, anyone shaped by a post-Enlightenment fixation on knowledge will find a persistent trope in Paul’s letters to be very odd, namely, his habit of linking love to knowledge—and granting priority to love. Consider, for instance, his ardent prayer for the Christians in Philippi: “that your love may abound more and more in knowledge and discernment, so that you might discern what really matters” (Philippians 1:9-10, translation by JKAS). What’s required for them to know, and to discern what really matters, is not a cerebral cortex loaded with beliefs, ideas, and knowledge. Instead, what’s required for knowledge and discernment is a properly functioning heart. Before I can know the truth, I first must learn to love.

This is the most important lesson I’ve learned from Augustine: that human persons, before they are “thinkers” or even “believers,” are first of all lovers. We are not primarily “thinking things,” nor are we fundamentally “believing animals.” Before we think or believe, we love and desire. We are what we love, and as creatures made in the image of God, humans are characterized by an essential desire that defines who we are: at the heart of our being is a kind of “love pump” that never shuts off. The brokenness of the Fall doesn’t make us stop loving; rather, it mis-directs our loves to improper ends (in Augustine’s technical lingo, we end up enjoying what we should merely be using).

According to Augustine, this is a structural feature of being human: we can’t not be lovers; we can’t not be desiring. The question is not whether we love but what we love. This is why I think Augustine’s premodern anthropology—his picture of the human person—provides a better framework for cultural critique in our postmodern age because it gives us new eyes to see the function of desire in our culture. The arena of the culture war is not centered on the heady realm of the Areopagus. It’s situated in the Pleasuredome.

Augustine’s understanding of human persons as erotic animals can help us to both recognize and understand the ubiquitous presence of sex in cultural phenomena from music to marketing. I want to suggest that this is not all bad. As an aside, “not all bad” should be a common judgment in accounts of culture like mine, influenced by Reformed Christianity. Given both the goodness of creation and its corruption by the Fall—that Christ’s Lordship extends to “all things,” as Paul teaches in the letter to the Colossians—our accounts of cultural phenomena will always have a “Yes, but” and “No, but” quality about them. There will (almost?) never be unqualified Yesses or Noes. That doesn’t mean there won’t be strident critique or robust affirmations, but such will always be qualified.

Victoria’s Augustinian Secret

I’m guessing I don’t have to convince you that sex sells, and that sex sells pretty much everything. It is so pervasive that we can become a bit blind to its ubiquity. We expect the association when someone is trying to convince us to buy cars or beer or body spray. But every once in a while the ubiquity of sex becomes just downright strange and jolts us into seeing again what is right in front of us. I remember, for instance, an advertising campaign for Uncle Ben’s microwaveable rice which basically promised that the time saved boiling water would translate into time spent in passionate sex with supermodels.

What’s particularly interesting, however, is the way in which marketing (and here one can include pretty much every aspect of the entertainment industry as ancillaries of the marketing industry) quite intentionally combines passion with transcendence, and combines sex with religion. In a culture whose civic religion prizes consumption as the height of human flourishing, marketing taps into our erotic religious nature and seeks to shape us in such a way that this passion and desire is directed to strange gods, alternative worship, and another kingdom. And it does so by triggering and tapping into our erotic core—the heart.

Thus one finds in marketing the promise of a kind of transcendence that is linked to a certain bastardization of the erotic. Certain modes of advertising appeal more directly to eros, to sexual desire and romantic love, and then in a baitand- switch move of substitution, channel our desire into a product— or at least associate the product with that desire and promise a kind of fulfillment. The standard versions of this tend to be crass, and directed to men (think beer commercials, razor commercials, or more recently ads for AXE body spray). But this is also true for marketing directed toward women: you might recall a line of shampoo commercials that promised various states of ecstasy that would attend mundane hygienic tasks like washing one’s hair. But the ubiquity of Victoria’s Secret is a particularly interesting case because it seems operative for both men and women. Victoria’s Secret ads appear during football games broadcast on ESPN and TSN. But the majority of shoppers at Victoria’s Secret are women who want to be desirable. And all of this is communicated by very affective, visual means: tiny narratives packed into images that appeal to our faculties of desire and inscribe themselves into our imagination. The secret here is an industry that thrives on desire and knows how to get to it.

A common “churchy” response to this cultural situation runs along basically platonic lines: in order to quell the raging passion of sexuality that courses its way through culture, we need to get our bodies and passions to be disciplined by our “higher” parts—we need to get the brain to trump other organs and thus bring the passions into submission to the intellect. And the way to do this is by getting ideas to trump passions. In other words, the church responds to the overwhelming cultural activation and formation of desire by trying to fill our head with “thoughts” and “beliefs.”

I want to suggest that, on one level, Victoria’s Secret is right just where the church has been wrong. More specifically, I think we should first recognize and admit that the marketing industry—which promises an erotically-charged transcendence through media that connect to our heart and imagination—is operating with a better, more creational, more incarnational, more holistic anthropology than much of the church. In other words, I think we must admit that the marketing industry is able to capture, form, and direct our desires precisely because they have rightly discerned that we are embodied, desiring creatures whose being-in-theworld is governed by the imagination. They have figured out the way to our heart because they ‘get it’: they rightly understand that, at root, we are erotic creatures—creatures who are oriented primarily by love and passion and desire. In sum, I think “Victoria” is in on Augustine’s secret.

Meanwhile, the church has been duped by modernity and bought into a kind of Cartesian model of the human person, and wrongly assumed that the “heady” realm of ideas and beliefs is the core of our being. (Of course these are part of being human, but I’ve been trying to suggest that they come second to embodied desire). Because we have bought into the modern “talking head” picture of the human person, the church has been trying to counter the consumer formation of the heart by focusing on the head. But they’re missing the target. It’s as if there’s a fire in our heart and the church is pouring water on our head.

A Romantic Theology

What if we approached this differently? What if we didn’t see passion and desire per se as the problem, but rather sought to re-direct it? What if we honoured what the marketing industry has got right—that we are creatures primarily of love and desire—and then responded in kind with counter-measures that focus on our passions, not primarily our thoughts or beliefs? What if the church began with an affirmation of our passionate nature and then sought to redirect it?

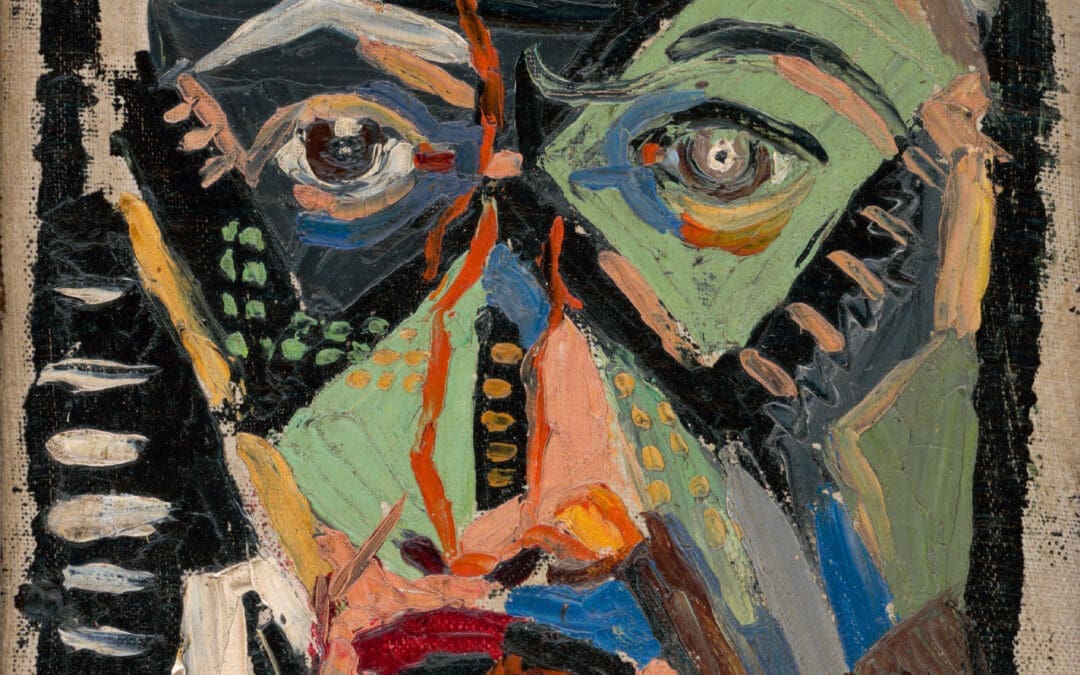

The result would be what the “Inkling” Charles Williams—a close friend of C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien—called a “romantic theology.” Developed in a number of unfortunately forgotten little books, Williams argued that the human experience of romantic love and sexual desire is itself a testimony to the desire for God. The same play is captured by some of the paintings of the Pre-Raphaelites, particularly by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, including his works portraying Dante and Beatrice. In fact, Williams would put it even more strongly: the person who experiences romantic love has experienced something of the God who is love. Treading a path opened by Dante’s meditations on Beatrice, Williams suggests in He Came Down From Heaven that romantic love “renews nature, if only for a moment; it flashes for a moment into the lover the life he was meant to possess.” Love, writes Williams in Outlines of Romantic Theology, is a testament to the intrusion or emergence of the divine in human experience, and thus is to be affirmed as an expression of our deepest erotic passion, the desire for God:

Any occupation exercising itself with passion, with self-oblivion, with devotion, towards an end other than itself, is a gateway to divine things. If a lover contemplating in rapture the face of his lady, or a girl listening in joy to the call of the beloved, are worshippers in the hidden temples of our Lord, is not also the spectator who contemplates in rapture a batsman’s stroke or the collector gazing with veneration at a unique example of [a stamp]?

One can see similar intuitions in Walker Percy’s Love in the Ruins or Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. The erotic—even mis-directed eros— is a sign of the kinds of animals we are: creatures who desire God. As Augustine famously put it, “You have made us for yourself and our hearts are restless until they rest in you” (Confessions, I.i.1). This is not a matter of intellect; Augustine doesn’t focus on the fact that we don’t “know” God. The problem here isn’t ignorance or skepticism. At issue is a kind of in-the-bones angst and restlessness that finds its resolution in “rest” —when our precognitive desire settles, finally, on its proper end (the end for which it was made), rather than being constantly frustrated by objects of desire that don’t return our love (idols). But this means that even desire wrongly “aimed” is still a testament to our nature as desiring animals. Operative behind Williams’s “romantic theology” is a picture of the human person that appreciates affectivity and desire as the “heart” of the person.

Bohemian discipleship

An Augustinian anthropology of desire primes us to adopt just such a romantic theology. This entails, I think, an interesting implication for how we think about learning and discipleship. I have in mind Moulin Rouge!—a film set in that den of iniquity, Montmartre, at the turn of the century during the fervor of the Bohemian revolution. A starving artist named “Christian” has rejected the “respectable” and bourgeois lifestyle of his father (as a clerk or saleman) and instead has sought to live a life devoted to literature and drama, all in the pursuit of beauty. He rejects the nine-to-five machinations of “normal” people, refuses to be reduced to a middle-class producer and consumer, and instead takes up with the colony of artists clustered in Montmartre—infamous home to burlesque shows and the “red light district” of Paris, but also home to painters and artists like Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Van Gogh—all taking place under the watchful eye of the Sacré-Coeur Basilica perched atop the hill. Thus Montmartre represents a certain mix of the sacred and the profane—both of which seem to be at odds with the bourgeois life of production and consumption the young literary bohemian Christian has rejected. The proximity to Sacré-Coeur almost invites us to look for parallels and comparisons between the bohemian artists and mendicant friars, both of whom reject a life of money-making for the sake of very different visions of the good life. But if both the bohemian and the friar desire a life that rejects the pursuit of comfort and wealth, could it be that there are some covert similarities between their visions of the good life? Does the Moulin Rouge already point up the hill toward the Basilica? What, at the end of the day, is “Christian” after?

Above all, Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge! is a “spectacular” love story revolving around the play within the play—a production of another love story, “Spectacular, Spectacular.” It is desire that brings the young man to art, to commit himself to the voluntary poverty of a bohemian literary existence. And it is in pursuit of this desire that another passion flares: his passion for Satine, a courtesan who reigns at the Moulin Rouge. Oddly, Satine herself represents the money-maker, concerned primarily with acquisition, as attested in her hymn, “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend.” (Indeed, her “profession” represents the very commodification of ‘love.’) Thus she resists his advances; above all she rejects his “bohemian ideal,” his naïve commitment to love (played out in the “Elephant Love Medley”). But love wins. Christian’s infectious commitment to love captures the heart of Satine and the effect is transformative: she, too, becomes a bohemian and the desire for acquisition gives way to a passion for love and beauty. Love even has a kind of epistemological or perceptual effect as indicated in their anthem, “Come What May”: “Never knew I could feel like this, like I’ve never seen the sky before.” The world is “seen” differently because of love. By the end of the film we learn that all of this has constituted a kind of education: “The greatest thing you’ll ever learn is just to love, and be loved in return.”

On the one hand, the Montmartre of Moulin Rouge! seems the very antithesis of the kingdom of God: a realm of prostitutes and addicted artists given over to wanton pleasure-seeking. This criticism is embodied in the figure of Christian’s bourgeois father, who berates the bohemian culture for its sinfulness, which seems to be most linked to its failure to be “productive.” But to “the children of the revolution” (try to hear Bono crooning the song from the soundtrack), our highest calling is not simply to be producers. Instead, they are committed to the bohemian ideals of “beauty, freedom, truth, and above all, love.” The spectacle of Moulin Rouge! is ripe for analysis in terms of Williams’s theology of romantic love—a love which is revelatory, which breaks open the world (“Never knew I could feel like this, like I never saw the sky before”). Christians, of course, will tend to say, “Ah, but that’s not love—that’s eros, not agape!” But a romantic theology refuses the purported distinction because it recognizes that we are erotic creatures. And so one could suggest that the good life looks more like Montmartre than Colorado Springs! The kingdom of God might look more like the passionate world of Moulin Rouge! than the staid, button-down, talkinghead world of the Christian Broadcasting Network’s 700 Club. The end of learning is love; the path of discipleship is romantic.