S

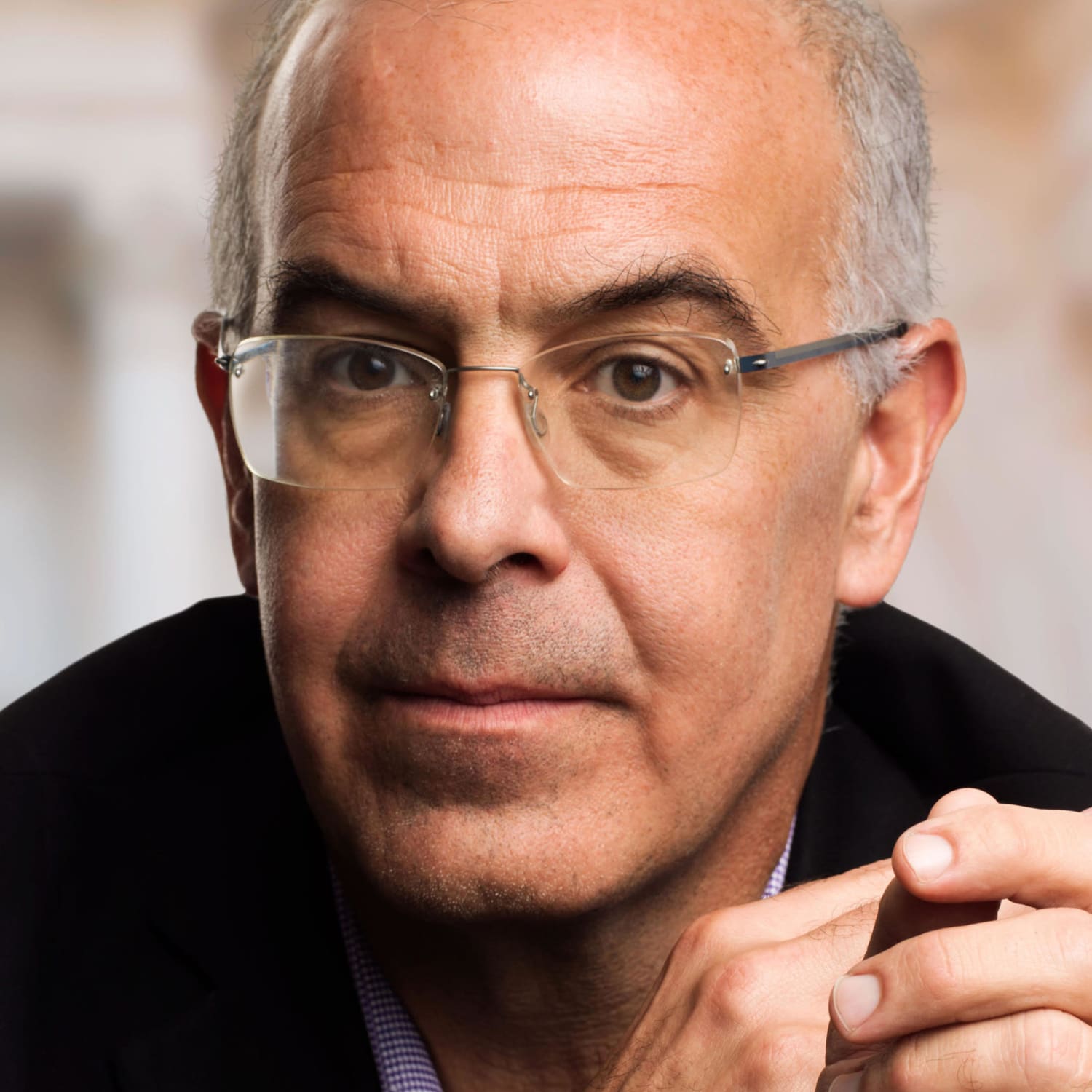

Single and twenty-six, Etty Hillesum was an immature and self-absorbed young woman. She was born in 1914 in the Netherlands and lived in Amsterdam with her brother and parents. She kept a diary, and in it her judgments of those around her could be harsh. She wrote that her mother was needy and narcissistic: “There was something terribly pathetic about her as well as something bestially repulsive.” She wrote that her father was weak and lost and had retreated into a world of vague philosophical ideas.

In May of 1940, the Nazis invaded. You’d barely know they were occupying Etty’s country from her early journal entries, which are self-focused and largely oblivious to world events. She saw herself with the same hypercritical eye she used to condemn her parents. “I am nothing more or less than a miserable, frightened creature,” she wrote. She saw herself as “a weakling and non-entity adrift and tossed by the waves.” “I long for something and don’t know what it is,” Etty confessed. “Inside I am totally at a loss, restless, driven, and my head feels close to bursting again.”

But over the course of 1940 and 1941, something shifted. She had grown up in a non-observant Jewish household, but somewhere along the way she began to pray. One night, she wrote in her journal, “I suddenly went down on my knees in the middle of this large room between two steel chairs and the matting. Almost automatically. Forced to the ground by something stronger than myself.” At first she felt embarrassed and awkward, calling herself a “kneeler in training.” But as the months went by, praying began to feel more natural, even imperative: “It is as if my body had been meant and made for the act of kneeling. Sometimes in moments of deep gratitude, kneeling down becomes an overwhelming urge.”

She started reading the Psalms, but her interests soon took her to Augustine and the Gospels. At one point, in the midst of the occupation, she copied a passage from Matthew into her diary: “Take therefore no thought of tomorrow: for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof.” At another she concluded that the world would only be saved if it embraced the vision of love described by “the Jew Paul” in his letter to the Corinthians. At yet another she wrote, “There really is a deep well inside me. And in it dwells God. Sometimes I am there too. But more often stones and grit block the well, and God is buried beneath. Then He must be dug out again.”

As the Nazi occupation lengthened, the physical conditions of her life grew worse and worse. But as Etty’s inner world was becoming more vibrant and attuned to God’s movements, her appreciation for the world’s beauty grew more intense. She would find herself stopping on the street, or in her apartment, overwhelmed by the beauty of a flower, the softness of a blouse, the scent of a bar of soap. The dominant tone of her diaries was no longer self-absorption and self-contempt, but something closer to reverence and gratitude: “Life is great and good and fascinating and eternal, and if you dwell so much on yourself and founder and fluff about, you miss the mighty eternal current that is life.”

In April of 1942, the Nazis began rounding up the Jews. Every morning, as Etty walked through her neighbourhood, she would hear the latest reports—about this father who had been taken away in the middle of the night, or about that family, which had simply disappeared. Many Jews were in denial about what was going on, but Etty saw the situation squarely: “What is at stake is our impending destruction. We can have no more illusions about that. They are out to destroy us completely, we must accept that and go from there.” As the months went by, she pulled prayer around her “like a dark protective wall.”

Jewish families began fleeing or going into hiding, and Etty could have joined them. Of the twenty-five thousand Jews who fled or hid, eighteen thousand survived the war. But she found she could not flee or hide. If Jews were to endure this suffering, she felt she should be with her people, serving them. Instead of running away from the suffering, she ran toward it. In June of 1943, she volunteered to go work at Westerbork, the transit camp where Dutch Jews were held before being shipped to the death camps.

She resolutely refused to hate the Nazis—refused to let Nazi barbarism evoke the same kind of barbarism in her own heart.

She worked in what was called the Social Welfare for People in Transit Department. That meant that she walked through the camp serving the prisoners in any way she could. She cared for the sick, helped people send telegrams back home, tended to those who had been sent to the punishment barracks and forced to endure hard labour. The other prisoners described her as bright, cheerful, and incandescent, full of a good humour that was laced with an undercurrent of sadness. Every week the trains would arrive to take another batch of condemned prisoners to the east.

She wrote letters to her family and friends back in Amsterdam, describing heart-rending scenes of families separated by the side of the trains, of a daughter holding her dying mother in her arms. She resolutely refused to hate the Nazis—refused to let Nazi barbarism evoke the same kind of barbarism in her own heart. Even amid the stench of death and genocide, her spirit could soar:

The misery here is quite terrible, and yet, late at night, when the day has slunk away into the depths behind me, I often walk with a spring in my step along the barbed wire. And then, time and again, it soars straight from my heart—I can’t help it, that’s just the way it is, like some elementary force—the feeling that life is glorious and magnificent, and that one day we shall be building a whole new world.

In September, Hillesum’s own name was on the list of those who were to be shipped to the death camps, along with her parents and her brother. They were herded onto the train, and somewhere along the route, Etty was able to scribble a note to a friend on a postcard and slip it through the cracks of the train car. It fluttered onto the ground, where it was found by a farmer and sent back to Amsterdam. Etty had written, “Opening the Bible at random I find this: ‘The Lord is my high tower.’ I am sitting on my rucksack in the middle of a full freight car. . . . We left the camp singing, father and mother firmly and calmly, Mischa too.”

She was killed at Auschwitz on November 30, 1943.

I offer you this mini-portrait because I am transfixed by the spiritual transformation that Etty Hillesum experienced. The horror of the Holocaust made some people passive and afraid. It made others bitter and ruthless. But Etty went from being a highly self-absorbed and critical person to being a selfless and generous person. As the environment grew more wretched, she became more tranquil and more radiant.

The horror of the Holocaust made some people passive and afraid. It made others bitter and ruthless. But Etty went from being a highly self-absorbed and critical person to being a selfless and generous person. As the environment grew more wretched, she became more tranquil and more radiant.

Hillesum’s biographer, Patrick Woodhouse, says something interesting about this transformation: “It was her practice of paying deep attention which transformed her.” Etty possessed what Woodhouse called an “acute perceptiveness.” Once she freed herself from her obsession with self, she was able to see other people in minute detail, observing one person’s rigid neck, another’s hungry look, another’s fearful eyes. She enveloped people in a loving gaze, a visual embrace that not only helped her feel what others were experiencing but also gave those around her the sense that she was right there with them, that she was sharing what they were going through, that here was another human being who saw them, understood them and made them feel seen. And she maintained this capacious, loving gaze even as the terror, callousness, and despair swirled around her. As Woodhouse puts it, “She was determined not to be numbed by the cruelty but to go on seeing.”

Hillesum was not the only young woman who experienced this kind of spiritual intensification in the tumult of that war. Like Hillesum, Edith Stein and Simone Weil were raised in Jewish homes. Like Hillesum, they had been brilliant students and possessed philosophical casts of mind. And like Hillesum, they became radiant and saintly as the tide of war enveloped them. In Stein’s case I mean this literally; she was eventually canonized by the Catholic Church.

But it is the shared quality of their transformation that I want to focus on here. These three women grew by looking. They changed the way they saw the world.

That may seem like a feeble and trivial form of resistance, compared to all the men who had taken up arms and were fighting and dying to destroy fascism. But it is not. As you look deeper into the lives of Hillesum, Stein, and Weil, you begin to appreciate that attention is a moral act, maybe the primary moral act. The quality of attention you bring to the world determines what you see in the world, and ultimately what you do in the world. She who only looks inward will only find chaos, and she who looks outward with the eyes of critical judgment will only find flaws. But she who looks with the eyes of compassion and understanding will see complex souls, suffering and soaring, navigating life as best they can. And if she sees others rightly, with the eyes of reverence, she will begin to treat others differently, with generosity and understanding.

These three women changed the way they saw the people around them, and were transformed. Or perhaps to put it more accurately, the Holy Spirit entered into each of their lives, and they saw the people around them by the light of that illumination.

Eight months before Hillesum volunteered to work at Westerbork, Edith Stein passed through the camp, also on the way to her death.

If anybody could understand the power of paying the right kind of attention to things, it was Stein. While a graduate student in her native Germany, around the time of World War I, she had earned her PhD under Edmund Husserl, the father of phenomenology. Phenomenologists focus on conscious experience, how we see the world and construct our subjective experience of it. Husserl taught his students to throw off prejudice, to discard the rationalist blinders that cause people to analyze experience prematurely, and instead to receive the world directly, with a humble, reflective attentiveness, with the whole of one’s being.

Stein pushed Husserl’s thought into realms where the master himself was hesitant to go. As a graduate student she wanted to know how people can project an empathetic gaze onto the people around them. She concluded that you can only cast this kind, other-centred regard if you are at peace with yourself. “Only the individual who experiences himself as a person, as an integrated whole, is capable of understanding other persons,” she wrote. If we are secure in ourselves, we won’t try to mold other people according to our own image but will simply seek to receive and accept others in their deepest essence.

As you look deeper into the lives of Hillesum, Stein, and Weil, you begin to appreciate that attention is a moral act, maybe the primary moral act.

Stein’s thinking was less abstract than Husserl’s, a quality she credited to her female eyes. “Woman naturally seeks to embrace that which is living, personal and whole. To cherish, guard, protect, nourish and advance growth is her natural maternal yearning,” she wrote. “Abstraction in every sense is alien to the feminine nature. The living and personal to which care extends is a concrete whole and is protected and encouraged as a totality. . . . She aspires to this totality in herself and others.”

Stein’s thought points to the idea that the most important truths are not abstract. They are incarnated in particular human persons. If you want to understand the world, don’t just analyze abstract arguments; get good at perceiving particular people.

In 1917, while still a graduate student, Stein went to visit a German widow whose husband had been killed in World War I. She was impressed by the widow’s faithful acceptance of her husband’s death, and her conviction that they would be reunited after her own. “This was my first encounter with the Cross and the divine power it imparts to those who bear it,” she later wrote. “For the first time I was seeing with my very eyes the Church, born from her Redeemer’s sufferings, triumphant over the sting of death. It was the moment when my unbelief collapsed and Christ began to shine his light upon me—Christ in the mystery of the Cross.” She came to faith by looking at a person.

Other personal encounters pulled her further up and further in. On a trip to Frankfurt, she saw a woman carrying her market basket make a detour into an empty church. “This was something new to me,” Stein noted. “Here was someone interrupting her everyday shopping errands to come into this church, although no other person was in it, as though she were here for an intimate conversation. I could never forget that.”

During the summer of 1921 she was staying at the home of another of Husserl’s students. One evening she picked at random a book from the shelf. The book was a memoir, The Life of Teresa of Avila. “I began to read, was at once captivated and did not stop until I reached the end. As I closed the book, I said, ‘That is the truth.’” Once again, she found faith by looking at a person and by being inspired by what—or perhaps more accurately Who—she saw moving in her.

Stein continued to think and write as a phenomenologist, but her views shifted and deepened. She began to argue that there are truths that faith can see that are invisible to unaided human reason. The light by which we see the world is not something we produce; the light enters us through the glow of God’s love, and then we radiate that light onto the world. Blessed with this gift of illumination, a faithful, uneducated person can see things in other people that the most learned scholar will not notice.

The light by which we see the world is not something we produce; the light enters us through the glow of God’s love, and then we radiate that light onto the world.

Stein asked her readers to imagine the sort of conventional person that society sees as a “good Catholic.” He does his duty, reads the right newspaper, and votes correctly. He spends his life more or less contented with himself. But for some reason he cannot see deeply enough into the hearts of others to truly be of service to them.

This good Catholic will try to change the unpleasant things in himself, but he will find that there are unattractive pieces of himself that he cannot change. He will be humbled by this realization. He will be more tolerant of the specks in his neighbour’s eye because he is more and more conscious of the beam in his own. “Eventually, he’ll be able to look at himself in the unblinking light of divine presence and learn to entrust himself to the power of divine mercy,” Stein writes.

As this happens, he will surrender himself and allow the Holy Spirit to take command. “The perfection of love does not consist in a certainty of knowledge but in an intensity of being seized,” she continues. It is only when he is willing to be seized that the Spirit can penetrate into the thoughts of the heart. It is only then that he can have the mystical experience that yields true vision:

The mystic is simply a person who has an experiential knowledge of the teaching of the Church: that God dwells in the soul. Anyone who feels inspired by this dogma to search for God will end up taking the same route the mystic is led along: he will retreat from the realm of the senses, the images of memory and the natural functionings of the intellect, and will withdraw into the barren solitude of the inner self, to dwell in the darkness of faith through a simple loving glance of the spirit at God, who is present although concealed. There, he will remain in profound peace, as in “the place of his rest,” until the Lord decides to transform his faith into vision.

Transforming faith into vision. This is one of Stein’s great ideas. It is the transformation she then proceeded to live out.

As the years went by and the quality of Stein’s faith deepened, so did the depth and compassion of her vision. Among other things, she became a Catholic. Hitler came to power in 1933. Stein found herself in the role of Queen Esther, one who had been separated by her people so that she could intercede for them before the powers of the time. She wrote to the pope and sought an audience with him. “For weeks, not only Jews but also thousands of faithful Catholics in Germany, and, I believe, all over the world, have been waiting and hoping for the Church of Christ to raise its voice to put a stop to this abuse in Christ’s name.” The Vatican refused her request.

The next year, at age forty-six, she felt called to become a Carmelite nun, taking the name Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. She entered the convent with women twenty years her junior. Life there did not come easily to her. It was apparently painful to watch her try to perform the simple acts of housework, like sewing, which she had not practiced during her years as a phenomenologist. Through her adulthood she had controlled her own time, but now she submitted to the rule of the order. Before she had been regarded as a philosopher and people came to her for advice; here people knew nothing of her former accomplishments and her former career. But as the years went by, she lost the solemn expression that had been her habitual presence and became more cheerful and serene.

She kept an eye on the outside world, especially the plight of the Jews. “You don’t know what it means to me to be a daughter of the chosen people—to belong to Christ, not only spiritually but according to the flesh,” she wrote.

News of Kristallnacht, in November of 1938, paralyzed her with grief. The next month, the prioress smuggled her across the border to a convent in the Netherlands, where, it was hoped, she would be safer. It was not to be. On July 11, 1942, the Dutch Catholic bishops protested against the mass deportation of the Jews. The Nazis retaliated by rounding up the Jews who had converted to Catholicism. Two SS officers arrived at Stein’s convent and announced that they had come for her and her sister Rosa, who by that time had also joined the order. They gave her five minutes to pack. “Come, we are going for our people,” Stein told her sister.

Prisoners who passed through Westerbork, but who survived the war, have left us with several accounts of Stein’s behaviour there. They describe her in the same way that people would later describe Hillesum.

“For all her quiet composure, there was a lighthearted happiness in the way she spoke to us. The glow of a saintly Carmelite radiated from her eyes,” one survivor wrote. “It was Edith Stein’s complete calm and self-possession that marked her out from the rest of the prisoners,” another testified.

“There was a spirit of indescribable misery in the camp; the new prisoners, especially, suffered from extreme anxiety. Edith Stein went among the women like an angel comforting, helping, and consoling them,” a Dutch official remembered. “From the moment I met her in the camp at Westerbork, I knew: here was someone truly great . . . like a saint. And she really was one. That is the only fitting way to describe this middle-aged woman who struck everyone as so young, who was so whole and honest and genuine.”

She was shipped off to Auschwitz on August 7, and died there upon arrival on the 9th. She was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1987 and canonized in 1998.

Simone Weil was born in Paris in 1909. She was a brilliant student. (Her brother André would go on to become one of the world’s leading mathematicians.) She was admitted to the best schools in France, studied philosophy—including Husserl’s phenomenology—and became a teacher in 1931. It seemed she was cut out for the life of an intellectual, but a core piece of her nature began to rebel against that destiny.

From early girlhood Simone had shown an intense identification with other people’s suffering. Even as a child she couldn’t eat if she felt others had no food. She had trouble settling into the conventional life of a teacher because she seemed oblivious or even hostile to the conventional wants that most of us share—to have a comfortable home, to have a secure income, to have respectful colleagues, and to settle into the comfort of family and friends.

Furthermore, she was never content with a life of contemplation. “The great human error,” she would later write, “is to reason in place of finding out.” If one truly wants to know, to see the world in all its reality, one has to enter into the world, experiencing it directly. “No thought attains its fullest existence unless it is incarnated in a human environment.”

So she didn’t just write about the alienation of the proletariat. She interrupted her teaching jobs and went to work in factories. She wanted to see firsthand what it was like. There, she was shorn of abstract illusions. She found that factory work was brutal, repetitive, and degrading. With her too-small hands, she was incapable of keeping up, perpetually angering her foreman.

Weil’s parents rescued her from the exhaustion of factory work by taking her on a vacation to Portugal. One evening there was a full moon over the coast and Weil saw the wives of the fishermen making a tour of the boats, carrying candles and singing hymns that she heard as “heartrending sadness.” She found herself tremendously moved. “There the conviction was suddenly borne in upon me that Christianity is pre-eminently the religion of slaves, that slaves cannot help belonging to it, and I among others.” Like Stein she was converted by looking at people.

There were other steps in her spiritual awakening. In 1937 she travelled to Assisi, home to St. Francis. “Something stronger than I compelled me for the first time in my life to go down on my knees.” The next year during Holy Week “the thought of the Passion of Christ entered my being once and for all.”

The Nazis occupied Paris in February of 1940. Weil and her family fled to Marseilles. There she met Father J.M. Perrin, a Dominican monk who worked with the refugees flooding into the city. He became a spiritual director for Weil—in conversation while she lived there and in letters in the years that followed. Perrin understood that Weil was leaving behind her intellectual understanding of things and moving toward a deeper, more mystical understanding. He would later write, “She was just then beginning to open with all her soul to Christianity, a limpid mysticism emanated from her; in no other human being have I come across such familiarity with religious mysteries; never have I felt the word supernatural to be more charged with reality than when in contact with her.”

He captured the essence of her quest: “She actually experienced in its heart-breaking reality the distance between ‘knowing’ and ‘knowing with all one’s soul,’ and the one object of her life was to abolish that distance.”

Weil was a mystic, but she never became a conventional Catholic. She was not a joiner. She had an instinctive refusal to belong to any group. So while she loved Christ and the Christian story, she was repulsed by the church, the church of the Inquisition, the church she associated with totalitarianism, the church that said this or that thought is not allowed.

Her spiritual quest, though, continued. She focused her thought on the same phenomenon that so transfixed Hillesum and Stein—the quality of attention. What is the proper way to see the souls who live, love, and struggle in this world?

Attention, she continued, is the “rarest and purest form of generosity.” It is the act of directing your whole being outward, turning away from self and opening oneself up to the experience of others. It is a willingness to not demand recognition from the world, but to give recognition. It is an intention to notice everything, appreciate everything. It is not imposing yourself on another person, but a willingness to subordinate oneself to another person, a willingness to follow their agenda, a willingness, she wrote, to see others “as they are related to themselves, and not to me.” Proper attention is the ability, she continued, to contemplate what cannot be contemplated—the suffering of another. It is the ability to absorb the beauty of another without trying to appropriate that beauty. It is the ability to simply behold another with a quality of reverence and awe, sympathy and fellowship. Prayer, Weil wrote, is “absolutely unmixed attention.”

Casting that kind of attention involves a self-surrender, a dying to self. When you are casting that kind of attention you are not investigating something, analyzing something, or mastering something, but rather receiving something. “Attention consists of suspending our thought, leaving it detached, empty and ready to be penetrated by the object,” she wrote. “Above all, our thought should be empty, waiting, not seeking anything, but ready to perceive in its naked truth.” Absurd ideas, she added, grow from the fact that someone has “seized upon some idea too hastily and being thus prematurely blocked, is not open to the truth. The cause is always that we have wanted to be too active; we have wanted to carry out a search.”

Simone had a Platonic conception of how we can grow in virtue, believing that we build character by focusing our attention on successively higher beauties. At first we contemplate physical beauty. “Beauty is the supreme mystery of this world,” Weil wrote. “It is a gleam which attracts the attention and yet does nothing to sustain it. Beauty always promises but it never gives anything.” Then we climb higher and learn to see the kind of human goodness that is more substantive than physical beauty, and earthly goodness that points to a transcendent goodness. “At the center of the hunger is the longing for an absolute good, a longing which is always there and is never appeased by any object of this world,” she wrote. If we turn our minds toward the good, “it is impossible that little by little the whole soul will not be attracted thereto in spite of itself.”

What is the proper way to see the souls who live, love, and struggle in this world?

Weil and her family left Marseilles in May of 1942 and made it to safety in New York. She went to Mass every day at a Catholic church on 121st street in Harlem. But Weil felt like a deserter, living in the New World as the Old World burned. She decided to go back into the suffering and got as far as London. She asked Charles de Gaulle to let her form a corps of nurses and martyrs. This would be a group of women who would join the men as they charged into battle, healing their wounds and sacrificing themselves for the cause. De Gaulle thought it was a crazy idea and dismissed it out of hand.

Weil was writing at a frenzied pace in these, her final years. One day, she composed an extraordinary prayer. She asked God to make her a paralytic, to make her incapable of receiving any sensations, to be rendered completely blind and deaf. She asked that she be made “insensible to every kind of grief and joy, and incapable of any love for any being and thing, and not even for myself.” She continued: “May all this be stripped away from me, devoured by God, transformed into Christ’s substance, and given for food to afflicted men whose body and soul lack every kind of nourishment. And let me be a paralytic, blind, deaf, witless and utterly decrepit.”

As you can see, Weil tended to take ideas to their extreme, to seek the pure, uncompromising version of any stance. This makes her an original and inspiring thinker, but it has to be said she could also be a repulsive one.

For one thing, she was a self-confessed anti-Semite. Etty Hillesum and Edith Stein identified with the Jewish people, and went to serve the Jewish people, and died for the Jewish people, even as their spiritual lives were directed toward Christ. Weil had renounced Jews all her life. She wrote that the Jews are an “artificial people” who possessed a “so-called religion.” She was virulently anti-Nazi, but at the very moment Jews were being shipped in boxcars to the east, she wrote this of the Jewish minority in Europe: “The existence of such a minority does not represent a good thing; thus the objective must be to bring about its disappearance, and any modus vivendi must be a transition toward this objective. In this regard, official recognition of this minority’s existence would be very bad because that would crystallize it.”

Granted, she wanted to erase Judaism through intermarriage and Christian education, not extermination—but her obtuseness is stunning, especially at the exact moment when that “disappearance” was being monstrously carried out.

Her mysticism also led her away from life itself. Ultimately Weil sought to see God in pure form by renouncing life in its bodily form. She sought “decreation.” “May God grant that I become nothing,” she asked. “We must become nothing, we must go down to the vegetative level; it is then that God becomes bread.”

In the summer of 1942, Weil developed a case of tuberculosis. She was taken to a hospital and would have probably survived it if she had been willing to eat. But Weil refused to eat. She decreated herself and hoped her death would be a sacrifice for those who suffered. She died on August 24, at the age of thirty-four.

In 1968, when the philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch was at the height of her powers and on the cusp of her greatest work, she wrote in her diary, “Have I come to the end of the path I started many years ago when I first read Simone Weil, and saw a far-off light in the forest?”

She had. Murdoch’s philosophy, especially in her 1970 book, The Sovereignty of Good, is the culmination of the journey that Hillesum, Stein, and Weil have been leading us on. This path begins with the idea that seeing the world is not just the passive act of opening your eyes and letting light flood in. Instead, perception is a creative and moral act.

As Murdoch puts it, moral life is not just making heroic acts of self-sacrifice at the epic key moments of life; moral life goes on continually in the small moment-by-moment acts of trying to cast “a just and loving regard” onto others. To see well we have to lay aside the egotistical, insecure, and self-serving lenses that most of us habitually use to construct comfortable versions of the world. As Weil had written, “the development of the faculty of attention forms the real object and almost the sole interest of our studies.”

What we have here is a different version of what the good life looks like, a version built on the seemingly simple act of seeing.

I’ll conclude with two questions. The first question is: Does it matter that the three thinkers I’ve described here were women? Was their femininity part of what caused them to adopt this shared moral philosophy?

I think it does.

Over the centuries, male writers and philosophers—think of Immanuel Kant—have built these vast moral systems that portray moral life as something that disinterested, rational individuals do by adhering to abstract universal principles: Always treat human beings as an end in themselves, and not as a means to something else. That emphasis on abstract universal principles is fine, I suppose, but it’s impersonal and decontextualized. It’s not about how this one unique person should encounter another unique person. It’s as if these philosophers were so interested in coming up with coherent abstract principles and philosophically impregnable systems that they became afraid of particular people—messy creatures that we are, and the messy situations we find ourselves in—and the personal encounters that are the sum and substance of our daily existence.

Maybe it’s partly culture and maybe it’s partly genetic, but over the long course of Western civilization it’s fair to say that men have been trained to think in this abstract, domineering way: to start from first principles, to lay down laws. Meanwhile these same men have often been blind to the networks of care right around them. Think of the way Thomas Hobbes was nearly oblivious to family life as he describes humans in a state of nature—“solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Women, through most of Western history, have, on the other hand, been charged with running these networks of care. It should not surprise us then that the philosophers most alert to the morality of personal encounter have been women. It should not surprise us that, during World War II, while millions marched and fled, fought and died, and history seemed to be unfolding on an epic scale, it was these brilliant women who were able to focus their attention on what was small, direct, and personal—the manner in which one human being gazes on another.

The second question is this: Does it matter that all three were born Jews? The issue here is complicated, because Weil renounced any sense of peoplehood. But I’d nonetheless say that their Jewish blood, their Jewish history, propelled each of them to a remarkable degree. In the first place, they were thrust into a circumstance of unfathomable moral intensity. They were living amid a European culture that they loved at the very moment it was trying to exterminate the people they were born into. That’s bound to produce a profound set of moral responses.

Furthermore, thousands of years ago Jews were a small, insignificant people living in a marginal part of the world. And yet they believed that God had centred history on them. It was an audacious conviction. And that notion has come down to Jews ever since in the form of a related responsibility: to live life as an audacious moral journey. God is not expecting great things; God is demanding great things—the life of the covenant. Live rightly and God will smile on you; live a life of moral mediocrity and woe will be your daily breakfast, bitterness your final sensation.

That pressure fuelled all three women—even to put their moral aspirations above their instinct for survival.

But most importantly, to be steeped in the Torah is to be steeped in particularity. It is a sacred book about particular humans—Abraham, Isaac, Sarah—in a particular place at a particular time. The abstract laws and commandments are incarnated in particular stories, stories that often defy expectations or generalizations. Why did Jacob do this and not that? Why did Ruth do this and not that? Attention is paid to the specific individual in the specific context. The sensibility is literary more than philosophic, Jerusalem more than Athens. Women steeped in this lineage are going to focus their gaze on actual persons before abstract ideas.

And then consider the circumstances. What is anti-Semitism (or racism generally) but the insistence, on the part of one human being, to not see another human being—to not recognize the depth of their soul or acknowledge their common humanity?

War is dehumanizing, and a war launched in part to exterminate an entire people is the most dehumanizing form of war imaginable. In the face of this onslaught, the most heroic and vital response is this one: I will see you. I will see you as the infinitely valuable and non-repeatable person that you are. I will see you whole.