T

The year is 1792. It is early autumn, and London is tense.

A few months before, the political philosopher Thomas Paine had published a pamphlet titled “Rights of Man.” It sold an extraordinary fifty thousand copies in its first weeks. Written against the backdrop of the American and French Revolutions, the book was highly critical of the hereditary principle that underpinned the British constitution. The government was scared by Paine’s popularity, and Prime Minister William Pitt sanctioned a violent hate campaign aimed at undermining him. Paine’s friends were attacked. The press bayed for his blood. Copies of the pamphlet were burned, while effigies of Paine hung in the street. Division was rife. The English had experienced civil war before. Was society inching toward that horror again?

On the evening of September 14, Paine was dining with friends, among whom was William Blake. The poet and painter had heard that the police were seeking to arrest Paine for seditious libel. “You must not go home, or you are a dead man!” Blake advised. Paine took note. That night he left England, never to return.

Political aggression that tips into bloodshed—that much feels familiar to us as, once more, passionate divisions grip Western societies. Some blame social media, others economic inequalities, others the scale of immigration. The diagnoses vary but appear to achieve nothing other than fanning the flames.

Back in the late eighteenth century, William Blake was also troubled by the deep unease. He had sympathy for the cause championed by the friend who had fled. “Is this a holy thing to see / In a rich and fruitful land: / Babes reduced to misery, / Fed with cold and usurious hand?” Blake wrote in his bitterly ironic poem “Holy Thursday.” But while he had, at first, understood and even shared the impulses of the revolutionaries in America and France, he now reacted differently. For Blake and Paine differed in one fundamental respect. The issue was theological. Alongside many of the founding fathers, Paine was a deist, while Blake was decisively not.

Amid the turmoil, Blake sought not a political, moral, or economic response but a spiritual one, offering a transcendent vision rather than a solution. At the heart of Blake’s theological reckoning in the deistic age of Paine was a wholehearted reassertion of theism and mystical Christianity—a way that, I believe, is illuminating for us now.

Blake rejected deism with a ferocity that is hard to overstate, accusing adherents of being nothing less than “enemies of the human race.” He objected to the naturalistic explanations that deists developed for morality and religion—explanations that seeded the atheistic convictions that are still widespread. You can say that deism forces Christianity through a sieve of reason. God is viewed as a distant designer of the cosmos. Jesus is taken to be a supreme moral teacher, with biblical stories read as a series of fables that, at best, convey ethical principles and, at worst, foster superstition. In deism, the primary aim of morality is to maintain social order, and the primary aim of religion is to police that morality for fear of eternal punishment by God.

What is now called “cultural Christianity” was born with bien-pensant thought leaders who argued that confessing the creed was good for society, even if the mind could not authentically follow. “A pretence of Religion to destroy Religion” was Blake’s assessment. He considered deist theology to be a perverse form of worship, implicitly venerating “the God of this World” by substituting social order for the kingdom of God, and therefore rewarding the “Selfish Virtues” of the human heart.

There was worse, so far as Blake was concerned, for gone as well was the radicality of the gospel. Jesus had taught an almost reckless insistence on forgiveness rather than retributive justice, offering redemption even for the worst of sinners. Deism, though, turned God into a blundering “Nobodaddy,” a patriarchal issuer of divine diktats. “Why does thou hide thyself in clouds / From every searching eye,” Blake asks, “Why darkness & obscurity / In all thy words & laws?”

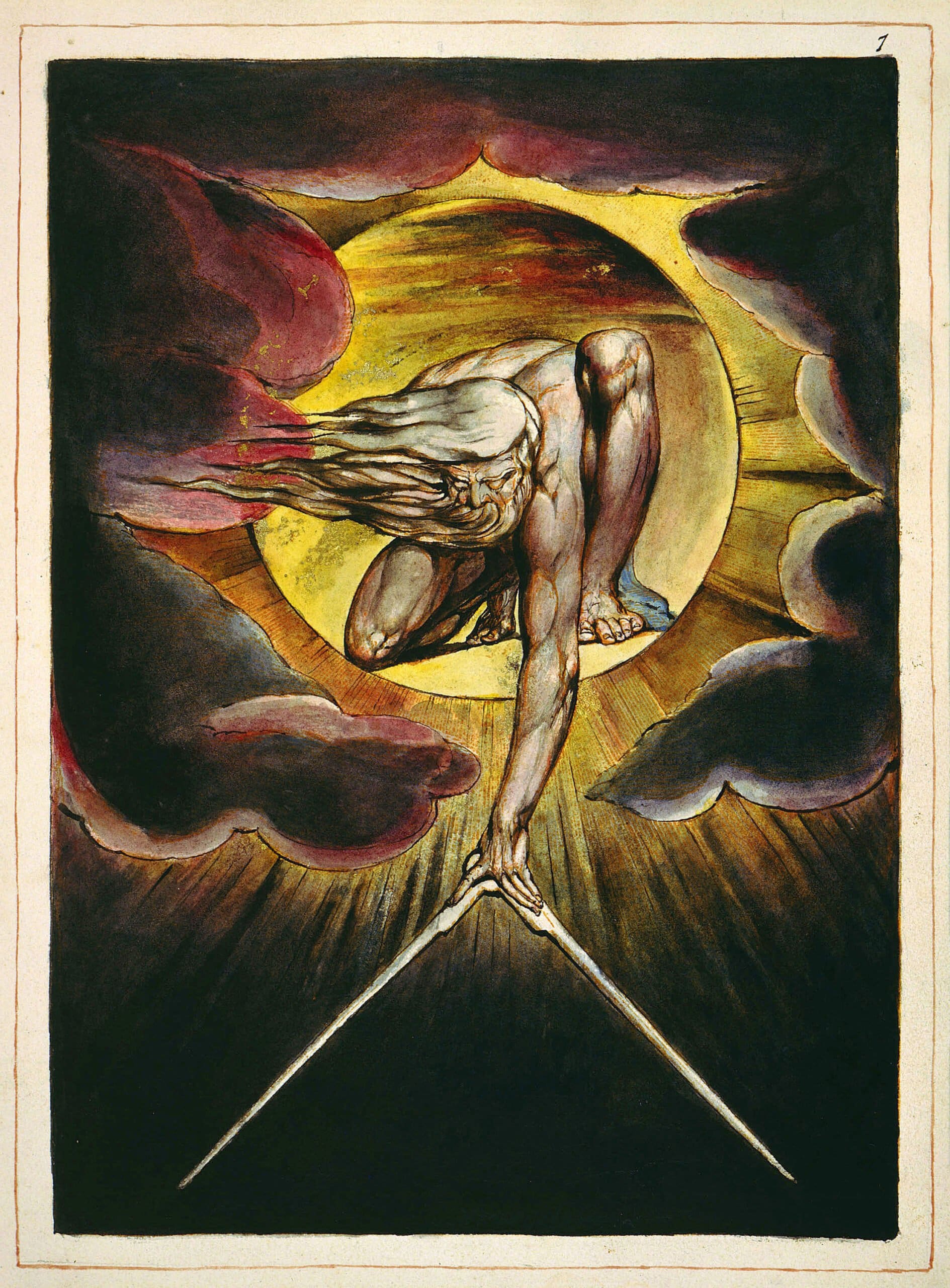

He had spotted that a Christian could confess faith in a loving father while possessing an operative image of God as an old man with a grey beard leaning from the clouds to control, not love, his creatures. The theological reframing was not just a devotional disaster but a social one too. Blake depicts this demiurge, which for him is functional atheism, in one of his best-known images, The Ancient of Days.

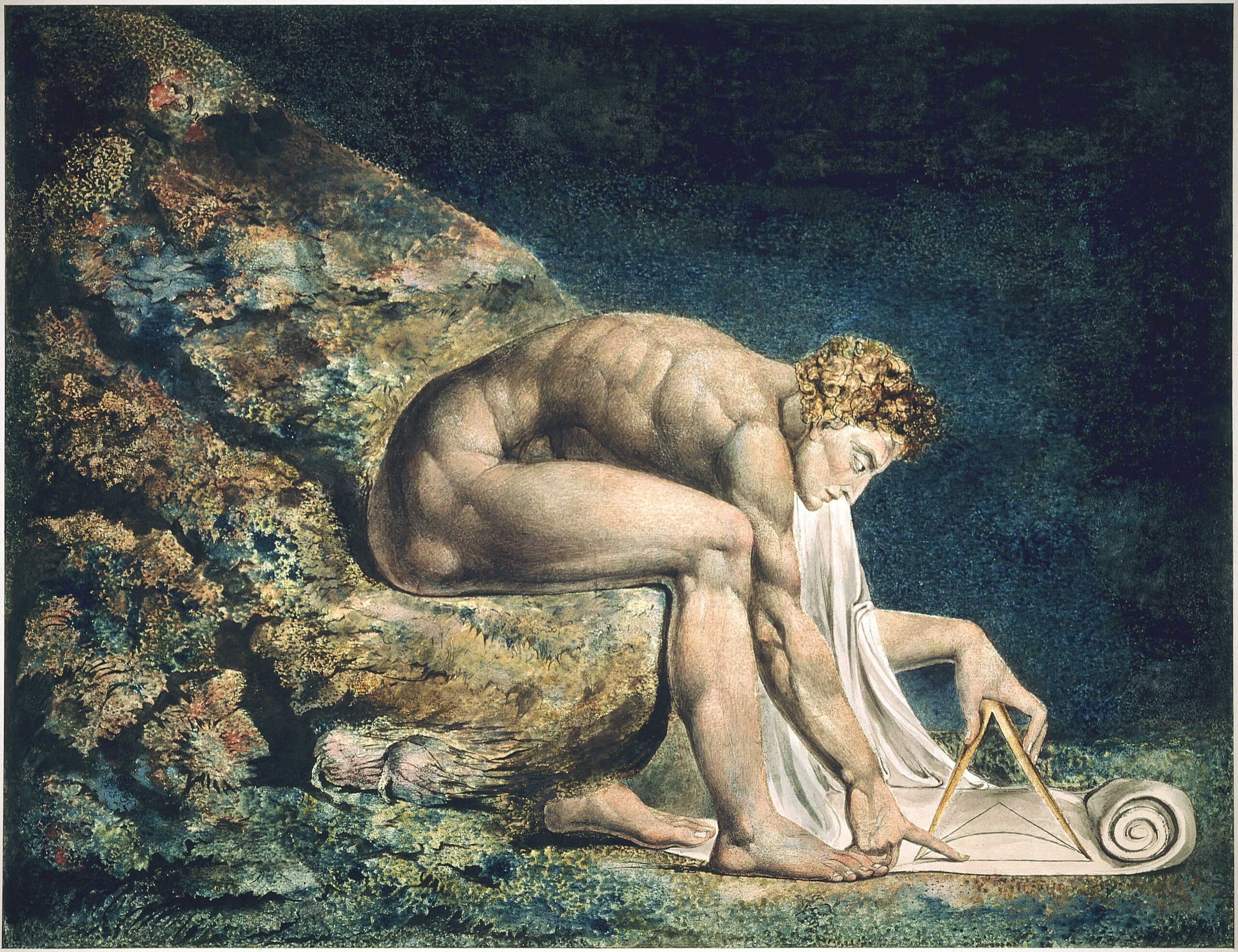

Deism gripped the minds of Blake’s contemporaries because of the extraordinary success of Isaac Newton, who lived just over a generation before Blake. The early modern physicist became a towering figure across the Georgian century because of a paradigm-shifting insight: Simple mathematical equations could be used to describe strikingly disparate phenomena, like how Newton’s law of universal gravitation could predict the movement of both falling apples and orbiting moons. That astonishing realization spurred the next generation of philosophers to seek similarly ordered relations for everything from government and education to morality and the mind.

Blake feared the new habits of investigation, which became the methods of science. The mechanical was usurping the imaginative; rigid principles of cause and effect were eclipsing the felt and sympathetic. The shift was not just about perceptions of the cosmos. Human beings were coming to view themselves in a parallel vein as receivers of sense data and processors of information, as the philosopher John Locke formulated it. These creatures, with their “blank slate” minds, were fundamentally isolated from one another because their consciousness was trapped inside their skulls. No longer did people experience themselves as open to the divine presence, the source of all vitality and intelligence. Instead, people began to feel cut off, quite possibly hallucinating reality rather than participating in it.

No longer did people experience themselves as open to the divine presence, the source of all vitality and intelligence. Instead, people began to feel cut off, quite possibly hallucinating reality rather than participating in it.

This physicalist worldview has become the default model of the mind in neuroscience today. And it has had political implications too. The development of naturalistic explanations seemed empowering to innovators like Paine because, as the science advances, so does the technology with which people might overcome material constraints. The steam engine was replacing the workhorse, transforming cities and towns in the Industrial Revolution. The new marine chronometer greatly aided seafarers, which boosted trade across the British Empire. Such economic gains sparked further dreams of social progress. As Paine had insisted, “We have it in our power to begin the world over again.”

Only Blake spotted the irony.

Paine’s enemies, the royals, claimed the same power to remake the world. The regularities tracked by Newton justified the maintenance of regularities in society, thereby providing a fresh rationale for monarchical authority. But Blake felt that the age of Newton and revolution was tragic. He believed that both sides looked to do well, but as governments and revolutionaries deployed the same justification for their actions, they were inevitably set on a course of conflict, not reconciliation. Blake brooded on the gathering of “dark horrors and thick clouds” and how a “mighty & awful change threatened the Earth.”

The tension spread into private life. Once deism recast Christianity as a moral creed, ethics began to present itself as a system—revolutionary in ambition, and still familiar in ours. Two rose in Blake’s lifetime and remain dominant: utilitarianism, which identifies the good with what maximizes happiness, and deontological ethics, which identifies it with adherence to moral absolutes.

You might recognize in both of these the two paths in which ethics is typically conducted today. Western governments daily justify policies on the grounds that they will bring the greatest happiness to the greatest number, and when that fails, ministers turn to rhetoric. “We do it because it is the right thing to do,” they insist. The trouble with both utilitarianism and deontology is they assume the human heart is as predictable as an apple falling to the ground. Which is to say that both moral systems treat desire reductively, effectively ignoring its imaginative and unexpected twists and turns. “It appear’d to Reason that Desire was cast out,” Blake observed. But, of course, human desires remain as powerful and confused as ever.

The new moralities, still very much alive today, judge everyone to be either right or wrong—which is why they cease to be about a way of life and instead focus on isolated issues: abortion, free speech, guns. “The moral virtues are continual accusers of sin and promote eternal wars and domineering over others,” Blake prophetically recognized. And the splitting became entrenched.

The period following the French Revolution generated a new kind of social categorization. Henceforth, people would place themselves either on “the left” or “the right.” The demarcation originated with whether post-revolutionary French politicians sat on the left or right side in the National Assembly. What was at first a location quickly became an identity, and, alongside cultural Christianity, the seeds of identity politics were sown.

By Blake’s spiritual analysis, human beings who lose their true identity seek proxies—the divine presence substituted with laws. If Blake were alive today, he might also insist that moral panics about the fragmentary impact of social media, say, lose sight of the causes and see only the symptoms of divisions. Digital platforms proliferate because the moral climate is essentially binary, sorting everything as right or wrong. Human relations mirror the tendency: for or against, like or dislike, friend or foe. The algorithm is merely an effective way of exploiting how the modern mind has been trained to perceive dualistically.

In the period after Paine fled England, Blake thought himself to be at an impasse. His differences with Paine and the establishment—coupled with his recognition that to join either side was to perpetuate the fundamentally deistic mindset—meant that he had to find an alternative route.

“I must Create a System, or be enslav’d by another Man’s,” he reflected. “I will not Reason & Compare; my business is to Create.” He had devised a spiritual critique of the times: Creativity offered a way out. If the root causes are “mind-forged manacles” and a narrowing of the imagination, the liberating focus must be on “Mental Fight” and releasing the imagination once more—for this human faculty, too, suffers under deism. Locke’s psychology enclosed it in the skull, there dedicated to helping forge a coherent model out of the sense data received from the otherwise inaccessible external world. But Blake insisted on something else: The imagination exists as much in the world as in our heads.

“Nature is imagination itself,” he cried, noting that “a fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees.” He didn’t mean that a person projects one set of assumptions not made by another. Rather, the “fool” is the human type conceived by Locke: a person who believes they don’t see the tree but rather an internally generated image of it, still the default model of the mind deployed by neuroscientists today. Blake’s wise person, though, realizes that they see the real tree because they inhabit the same space of continual unfolding. This boundless field of vitality is, for Blake, the divine imagination active throughout the natural world, continually making and sustaining it. There is no place to be cut off from this outpouring of creativity and spirit.

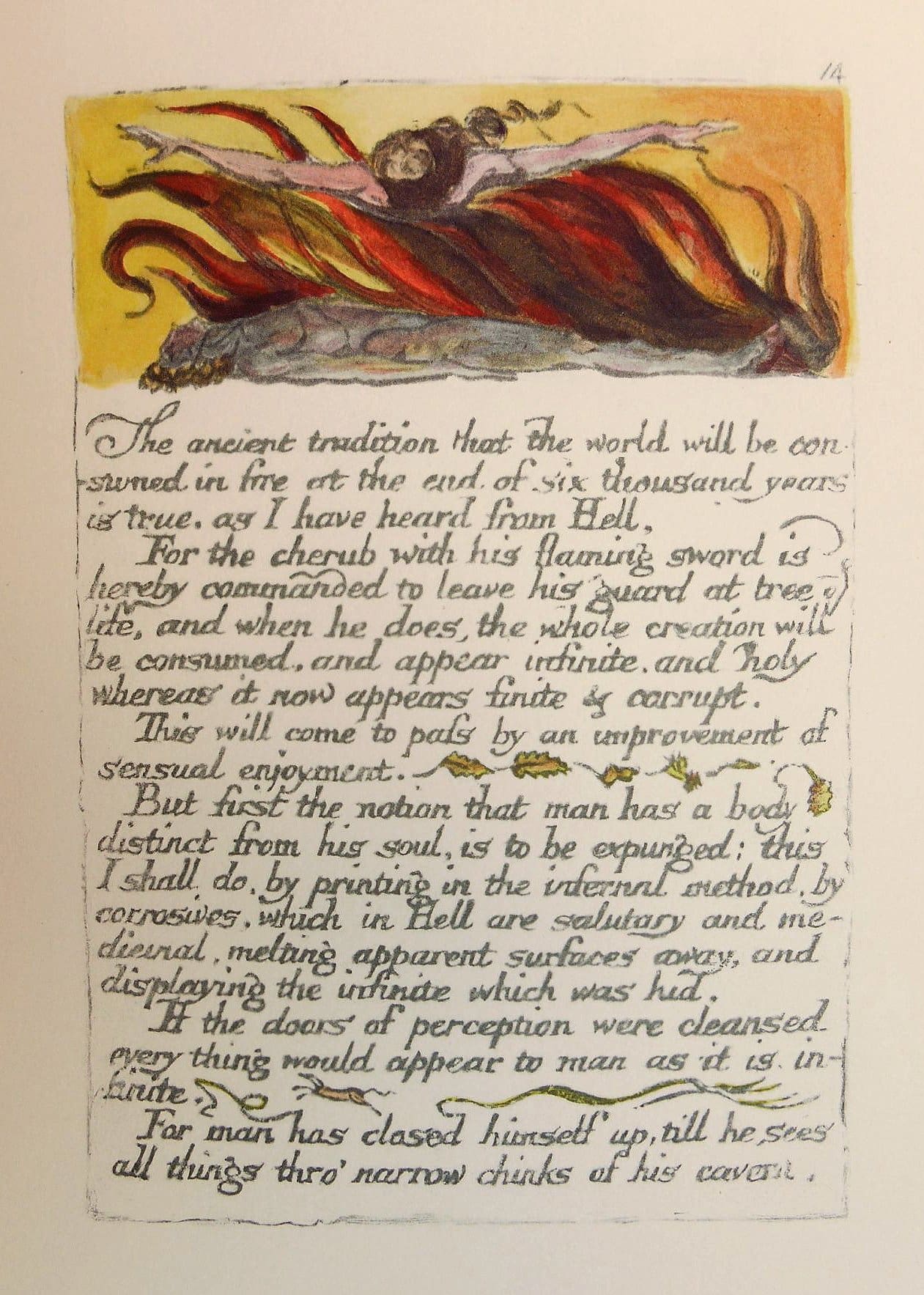

A similar argument is pursued in one of Blake’s best-known sayings: “If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is: infinite.” The line is often taken as a reference to a peak experience or psychedelic trip, thanks to Aldous Huxley, who called his autobiographical account of his experiences on mescaline The Doors of Perception. However, Blake meant something else entirely: not an exceptional moment of connection but the continuous connection that is the truth of everyday life.

A clue to the richer interpretation is found in the oddity of the phrase “doors of perception.” Wouldn’t “windows” make better sense, since the organs of the empirical senses—eyes, ears, and so on—are apertures through which our bodies receive information about the world? But Blake resisted the way that Lockean psychology turned these windows into doors that shut out the world. What needed cleansing was the philosophy itself. The senses have always been what they are: portals through which human beings participate in the world around them. Eyes and ears are not sense organs but, more fully, “the chief inlets of the soul.” When that is once more seen aright, Blake realized, all things could radiate with the infinite source from whence they spring, for “every minute particular is holy.”

Blake is as much a philosopher as a poet, given his penetrating analysis of how the new psychology cuts us off from life. But the poetry adds a further element to his cool deconstruction of Lockean assumptions. The verse and songs, images and rhymes, are crucial because they convey the energy of life, which, transcending strife, can create space for more.

For Blake, the imagination not only floods the cosmos but gushes from the divine wellspring, which is the continual creativity of an ever-present God. “I am in you, you in me, mutual in love divine,” Blake hears God say at the beginning of his epic poem Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion. “I am not a god afar off. I am a brother and a friend,” the divine voice continues. Individuals need not regard themselves as divided, because each and every one finds their identity in that shared source. Difference need not, therefore, be a threat but a revelation of the many manifestations of the infinite that are incarnate in the world.

The embrace of variety also implies that nothing can be treated as a pure object, amenable to human manipulation, but is instead another part of the one expression of divine life. Human activity, therefore, which necessarily includes elements of extraction and manipulation, must never lose touch with the wider context of relationship and shared source.

For Blake, the imagination not only floods the cosmos but gushes from the divine wellspring, which is the continual creativity of an ever-present God.

Blake holds the two facets together through the integrating power of poetry. Take his line “When nations grow old, the Arts grow cold, And Commerce settles on every tree.” The meaning is straightforward enough: Trees become objects of commercial exchange among developed nations driven more by markets than imagination. But then add the beat set up by “old” and “cold,” and link that with the image of commerce settling on trees like snow. The meter and description free the imagination otherwise narrowed or lost. The analysis brings an antidote—namely, the energetics of poetry that are part of Blake’s alternative way.

In another much-loved couplet, Blake writes, “To see a world in a grain of sand, / And a heaven in a wild flower,” which brings an inspiring experience to mind and sparks a desire to know more of such awareness. “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom” is yet another. It refers not to libertinism but to the proximity of the transcendence present in all “minute particulars,” unpacked by Blake’s philosophy, which promises release from binary ethics into a higher form of wisdom. That wisdom is why we need Blake now, and, I think, why people intuitively respond so warmly to him.

Today, some do seem to be following Blake’s approach. They intuit that political struggles are fundamentally theological, as Blake saw. That said, the insight brings its own risk because, unless the deistic impulse is transformed, the temptation is to deploy Christianity as an identity: a way of separating those deemed enemies, secular, or even satanic. But Blake’s Christianity of forgiveness and redemption is radically different.

Consider how he understands the story of the woman caught in adultery. John’s Gospel (8:3–11) describes how some scribes and Pharisees, by this stage enemies of Jesus, bring before him a woman caught in flagrante delicto. They aim to test his loyalty to the Mosaic law, which instructs that she is to be stoned; they hope that Jesus will hesitate on this matter so that they can accuse not only her but him as well. In response, Jesus bends down and writes with his finger on the ground, then utters famous words: “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.” He bends down again and writes once more as the accusers depart one by one. Jesus is now alone with the woman. No one has condemned her, and so he adds, “Neither do I condemn you; go, and do not sin again.”

Blake painted the moment when Jesus is bent down and writing for the second time as the accusers disperse. The woman is not yet free, because Jesus, being without sin, is the only one who might cast a stone. Yet in the image it appears as if he is not only writing but also bowing down before her.

Blake describes the woman in the image as if poised between a series of “contraries”—of life and death, love and hate, freedom and condemnation. Moreover, Jesus is in the same state as her; the backs of the accusers remind us that her enemies are his. In other words, his bow to her is an act of recognition. They dwell together, one in another, simultaneously pointing to the divine love that enables such mutuality. Blake is highlighting Jesus’s Johannine teachings; as Jesus say to the Pharisees on another occasion, “You are gods” (10:34). And as he makes clear in the prayer of John 17, all are one in God as he is one with the Father.

The woman’s moment of potential condemnation is therefore transformed by Jesus’s judgment. He judges her not to divide himself from her but to point her to her true nature, which is as his. He and she are in “the human form divine,” as Blake puts it. And the implication is that we, contemplating this moment too, are co-participants in that divine image.

William Blake offers a spiritual analysis of and antidote to the deadening, atheistic missteps of his times—and ours. His insights, imagery, and verse cultivate an awareness that is at once felt and understood, and which can renew the divine vision of ourselves and the world around us.

Figures like Locke strove to reformulate the sense of who we are as human beings for honest reasons, in response to the astonishing achievements of Newton. But the price paid has been too great: nothing less than the construction of a seeming gulf between our minds and the inner life of all that exists around us. For our desire is not law-like, and it becomes trapped by overweening laws. Our yearning, with all its good aims and poor mistakes, is not best served by codes of conduct or calculations. The wider, restorative perspective that Blake offers renews the imagination and loosens the hold of what he called “the Wastes of Moral Law”—a wasting so apparent now.

Redemption of our times will therefore come with a shift of consciousness. That perceptual revolution emerges when the dualisms currently so dominant—right or wrong, left or right, for or against, friend or foe—are held as the precursors to a yet largely unimagined transfiguration. And that transformation will come with the “Mental Fight” that reveals afresh the truth about us and all things. The promise of Blake, and of mystical Christianity, is a vision and energy greater than any outrage. “He who sees the Infinite in all things sees God,” Blake affirmed, adding, “He who sees the Ratio [another dig at deism] sees himself only.” Or, as he signed off a letter to a friend: “May God us keep / From Single vision and Newton’s sleep.”