N

Not long ago, I took a friend to a stationery shop to look at fountain-pen inks and paper, thinking she’d be enthused. Instead she was puzzled. “I almost never write anything down. Why would I?” I grew up in the late 1980s and 1990s in India and Brunei, where technology lagged behind other, more industrialized countries. The practice of writing letters and postcards seemed as natural as teenagers thumbing smartphones today.

In his luminous biography of the writer V.S. Naipaul, The World Is What It Is, Patrick French muses that his might be one of the very last works on a subject whose works and correspondence were completely by hand. One can imagine French sifting through old manuscripts with marginalia, confronting the tangible detritus of the fragments that make up a life to get a sense of the whole.

I find it rather easy to be carried away by nostalgia, to pit analog against digital modes of communication and bemoan what has been lost. What’s increasingly evident to me is how brittle the signs we give each other actually are. Of course, a tranche of digital files can be lost as easily as a pile of letters in a fire. But I still cannot help feeling a fascinating congruity between holding physical correspondence in my hands and sensing more deeply the intimacy it represents.

A recent spring cleaning afforded a confrontation with what I call my memory box, a stash of old, dear things from others. A select number of them have afforded me the chance to meditate more concretely on the forms and meanings of friendship.

In Dante’s great hymn to the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Paradiso canto 33, there is a hello to St. Joseph hidden as an acrostic in the original Tuscan. An Italian friend first pointed this out to me in a reading group, and I’ve appreciated this paean to a faithful man who was silent but a steady doer.

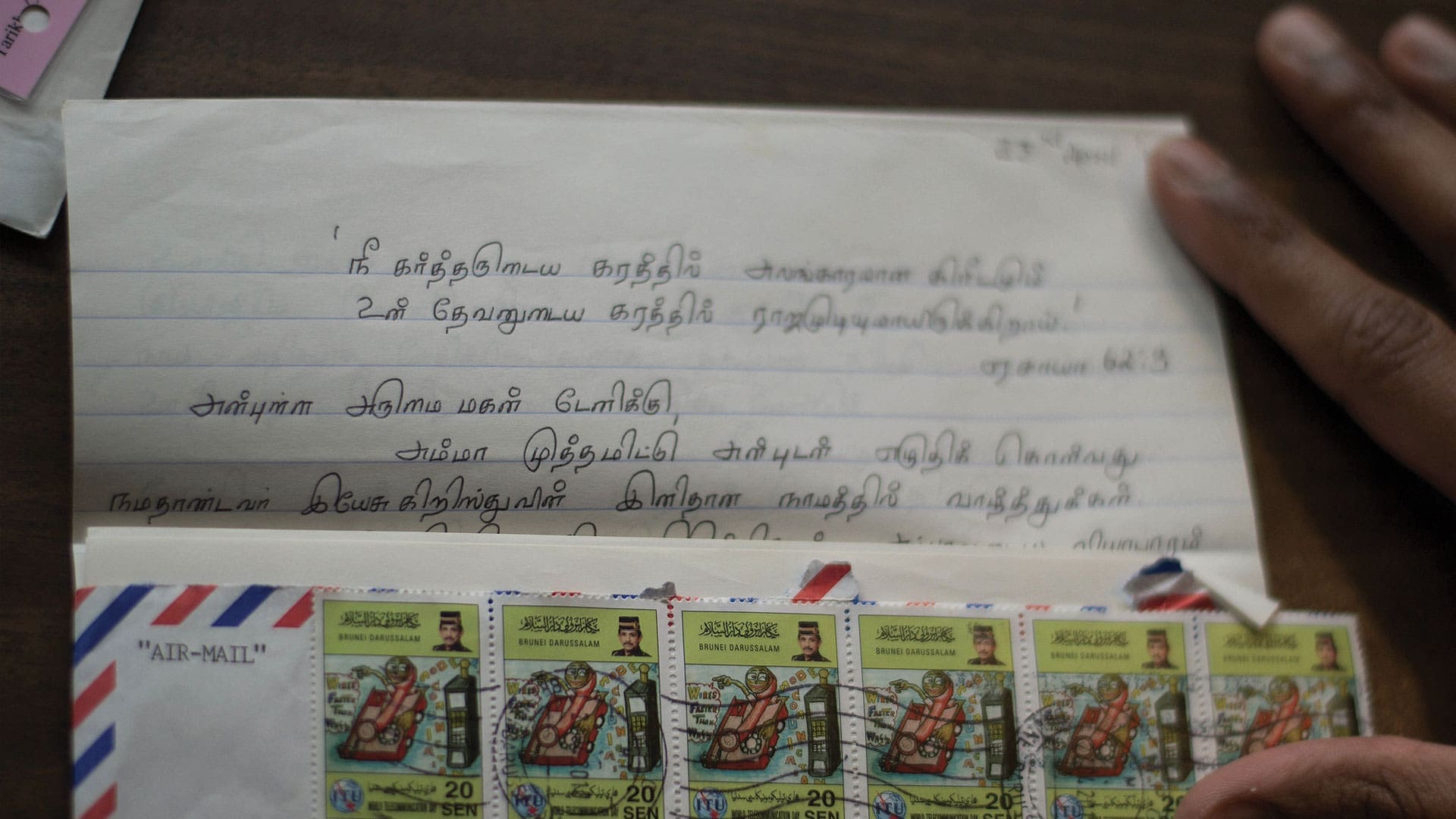

The first thing I noticed in a letter written in Tamil from my mother is my father’s neat, typewritten form on the face of the retro blue-and-red-striped airmail envelope. Even though he had not said anything directly, his act of certifying the accuracy of the addresses and ensuring sufficient postage spoke volumes about his care. My mother writes with an elegant script, and her affection and concern overflow in these pages, bringing me solace many thousands of miles away. The word for parents in Tamil, amma-appa, is simply the compound of mother and father, and I cannot help but think of them together.

I’m not sure exactly when the transition from being an annoyed dependent to an appreciative friend between parent and child happens, but it’s really rewarding when it does. It gives a newer vantage point and an appreciation of their humanity. This is especially true when we’re separated by geographical distance, when the dross of daily bickering gives way to a healthier regard for the best qualities of each other. (In fact, I’m compelled to think that a physical separation is necessary.) The duality of parental authority and friendship contributing to one’s maturity has echoes in the Christian proposal of a relationship with God. Christ calls his disciples friends and yet mediates this friendship by asking us to do what he commands (see John 15:14–15).

The sense of being loved and embraced by those given the task to rear and form us is a great gift, and the chance to mature into a friendship with them helps each of us discover its true nature.

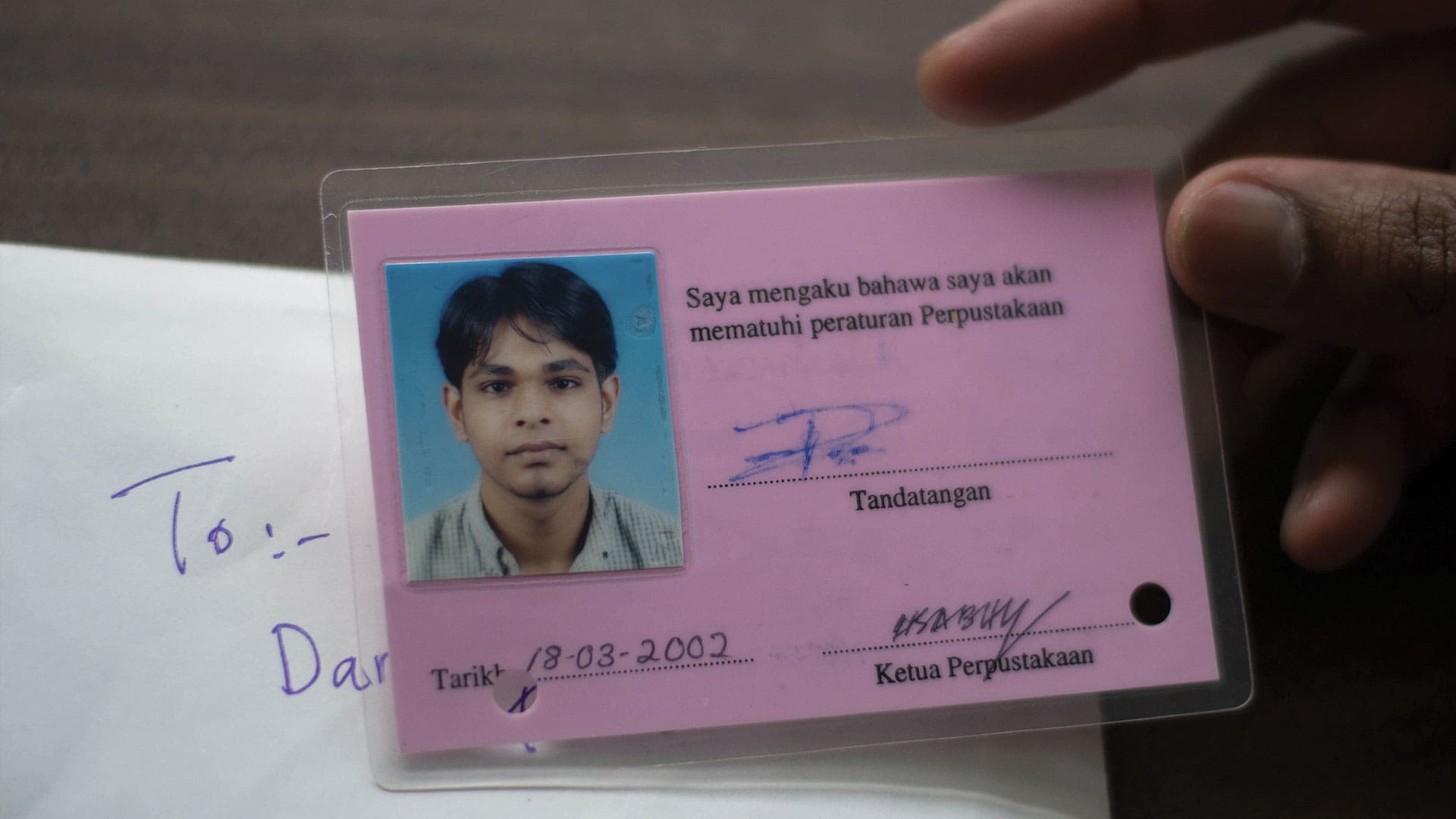

One of the youth group materials during my adolescent years in Brunei stated that there is no junior Holy Spirit. It gave me an early reassurance that the presence of God could meet me fully, and that depth could not be denied anyone, no matter their age. Of the many profound friendships cultivated during these formative years that continue to endure today, one stands out. This friend’s youthful, handsome image stares back at me from an old, pink, laminated public school library card inscribed in Malay. He gave it to me just before I was to leave for Canada, along with a note—something to remember him by. While we’ve had a few more memories (not enough) in the almost two decades since, there is a steadiness in our intimacy that I continue to cherish.

I am reminded that it is essential in friendship to remain faithful to those who have indelibly marked us in our youth, as those early bonds can be as profound as or even more so than those that emerge in our riper years.

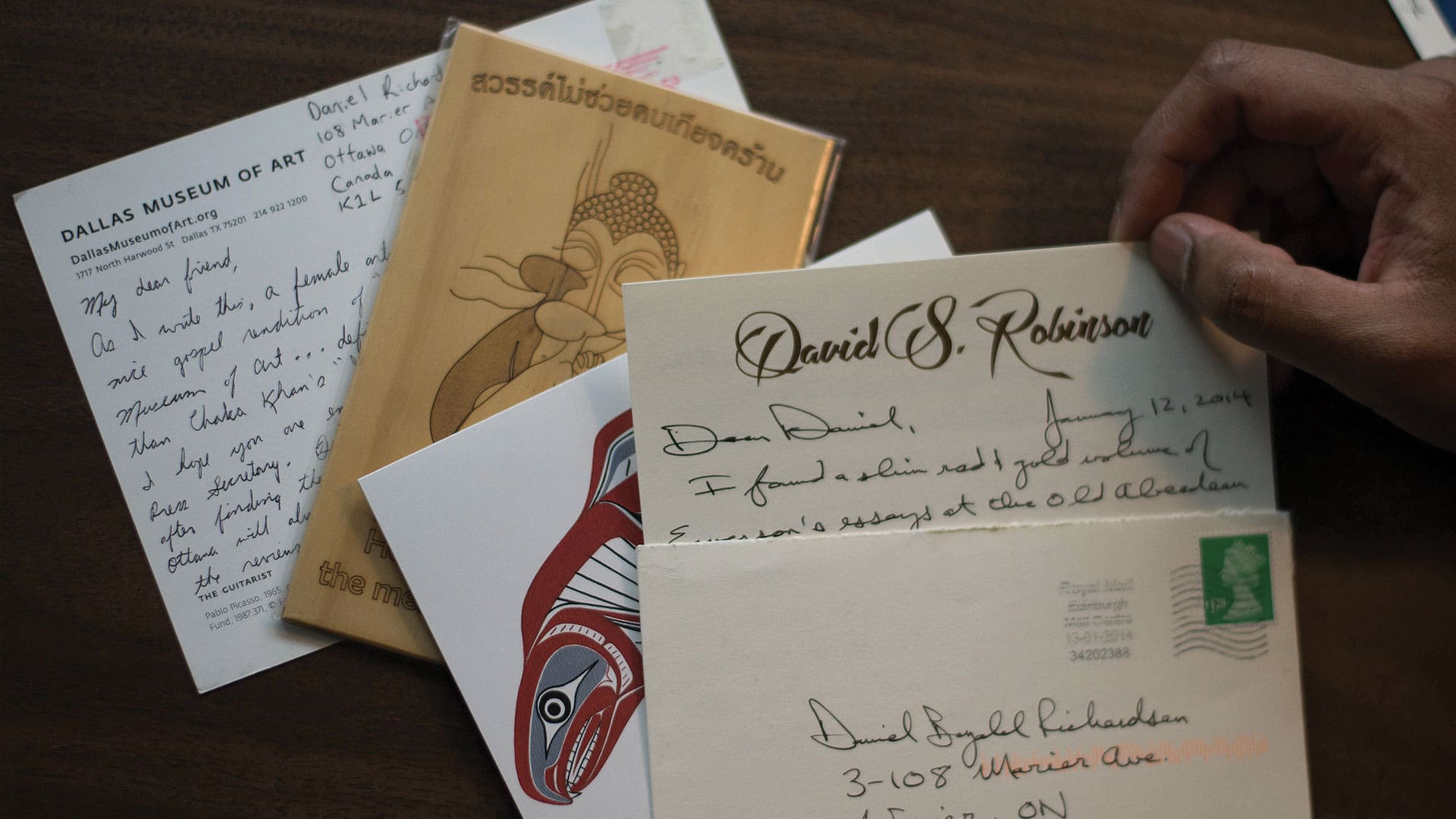

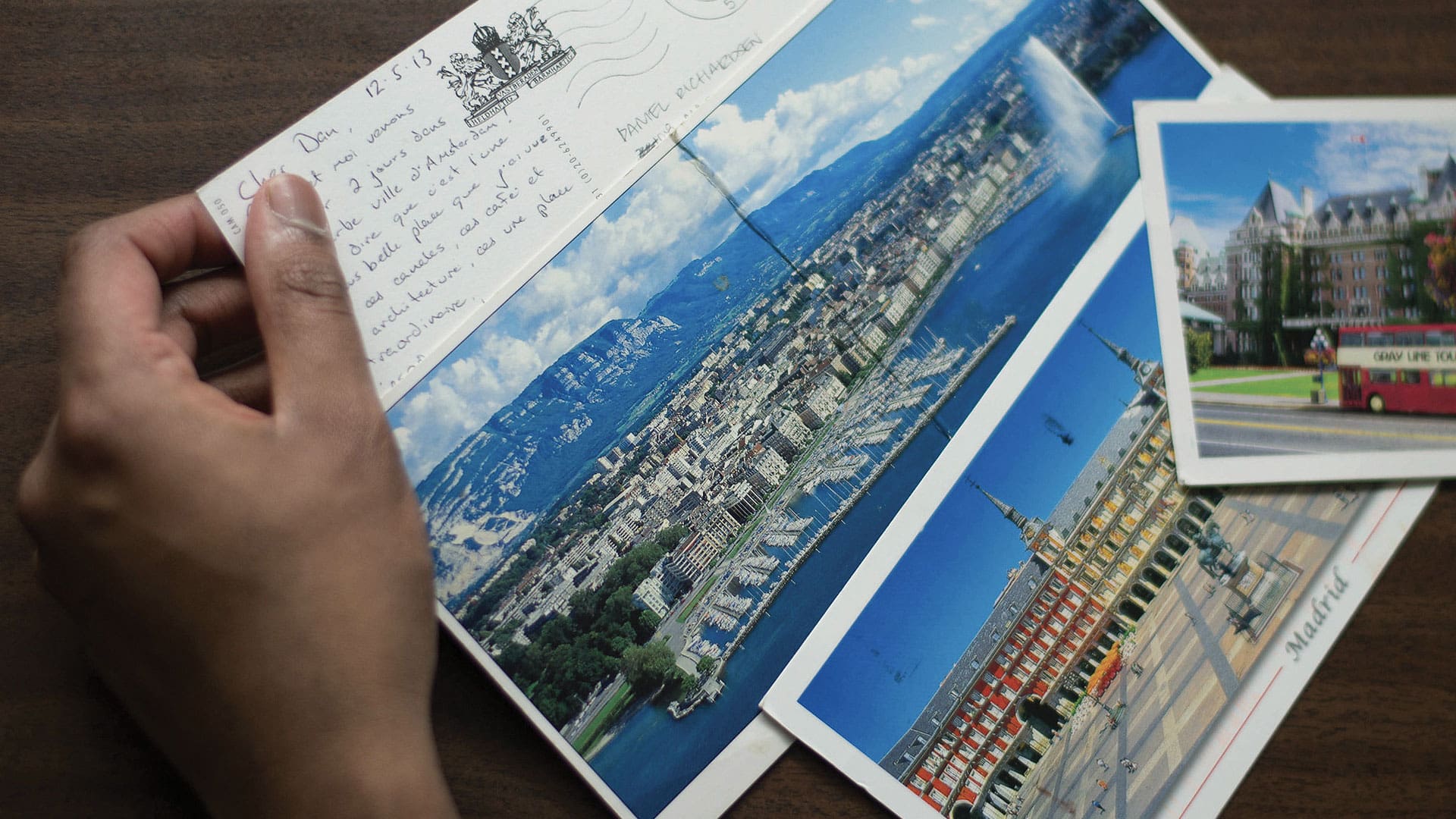

I first picked up Meg Jay’s book The Defining Decade: Why Your Twenties Matter—and How to Make the Most of Them Now when I was twenty-nine. While initially struck by panic imagining all the things I was probably behind on, I was heartened that one of the crucial gifts during this stage (or any stage) is the importance of peer relationships. While adolescent friendships and the love of parents can anchor us, it is embarking on the adventure of risk-taking and discovery that requires the accompaniment of peers. Not dependents, and not those one would look up to, but those walking at an even pace very close to you on the same road. The defining decade also happened to be the most vulnerable one for me so far, or at least it appeared so, because my responsibilities contrasted so acutely with my inadequacies. The letter in the foreground and those blurred behind it were written by some of these very peers who helped sharpen me and console my doubts, and who offered me the chance to do the same for them.

One of the pitfalls I’ve sensed is to treasure the effects of these peer friendships rather than the friends themselves. I have been learning the importance of staying beside the same friends, even as our lives change and grow and the unencumbered attention and intensity that we could once afford to shower on each other wanes and our attention is focused on vocations that have emerged more fully. Even when they can do nothing for me—no projects to enroll in or adventures to be embarked on—they are still to be treasured.

Even when those friendships can do nothing for me—no projects to enroll in or adventures to be embarked on—they are still to be treasured.

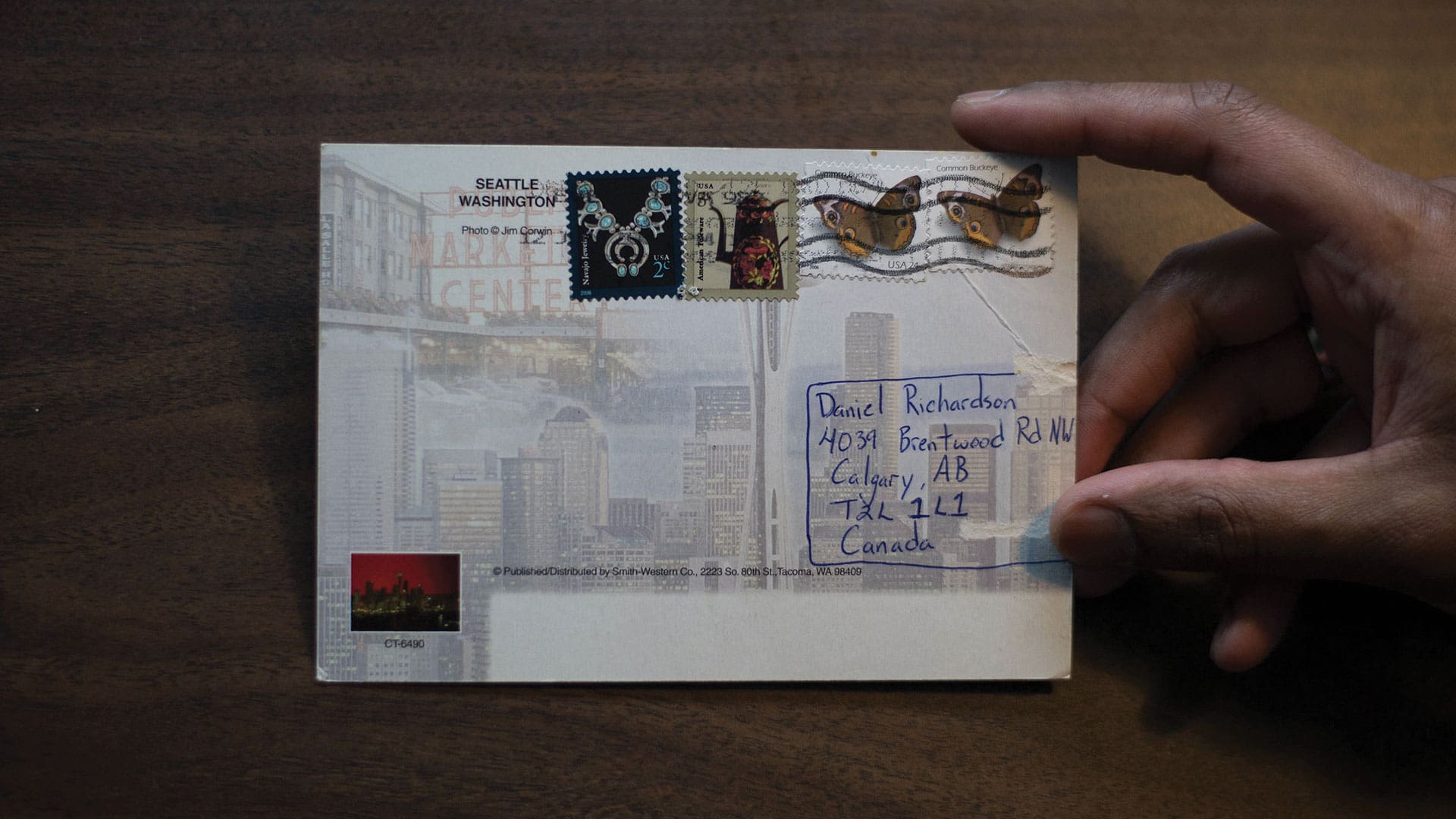

One of my close friends from my first years in Canada was spending his summer in Seattle while I spent mine in Calgary. I’d asked him to send me a postcard when he got the chance, in anticipation of visiting him and the Pacific Northwest for the very first time. I still recall the strange juxtaposition of my responses upon receiving the postcard in the mail: of my smile upon seeing the skyline of Seattle on the cover and my total befuddlement upon turning it over and seeing just my name and address and a totally blank space where one would normally expect a message. He told me later he had filled in the address and placed the stamp ahead of time but wanted to think more carefully about what he’d write. An aunt, however, posted it accidentally before he had written anything. Whatever the truth of the matter was, I prefer to think he posted it himself on purpose out of sheer mischievousness: “You wanted a postcard? You got it!” We still laugh about it years later.

It is a reminder to me of the importance not just of earnestness but also of levity, of how important it is to laugh, and laugh together. I have been learning that mirth is such an important antidote to fear, and certain friends in our lives remind us of this. They seem to carry themselves lightly, and help us to do the same. They draw out the things that are funny and remind us of the joy of being alive, but they also give us courage to laugh at lies and evil because for the Christian it is not these things but Christ’s death and resurrection that have the last word.

One of the finest contemporary depictions of intergenerational friendships is in Gus Van Sant’s film Finding Forrester. A young African American teenager from the Bronx befriends a recluse who may have written the great American novel. The unexpectedness of how events unfold in the movie is an antidote to fearing an encounter with others different from ourselves, and also the fear of being surprised.

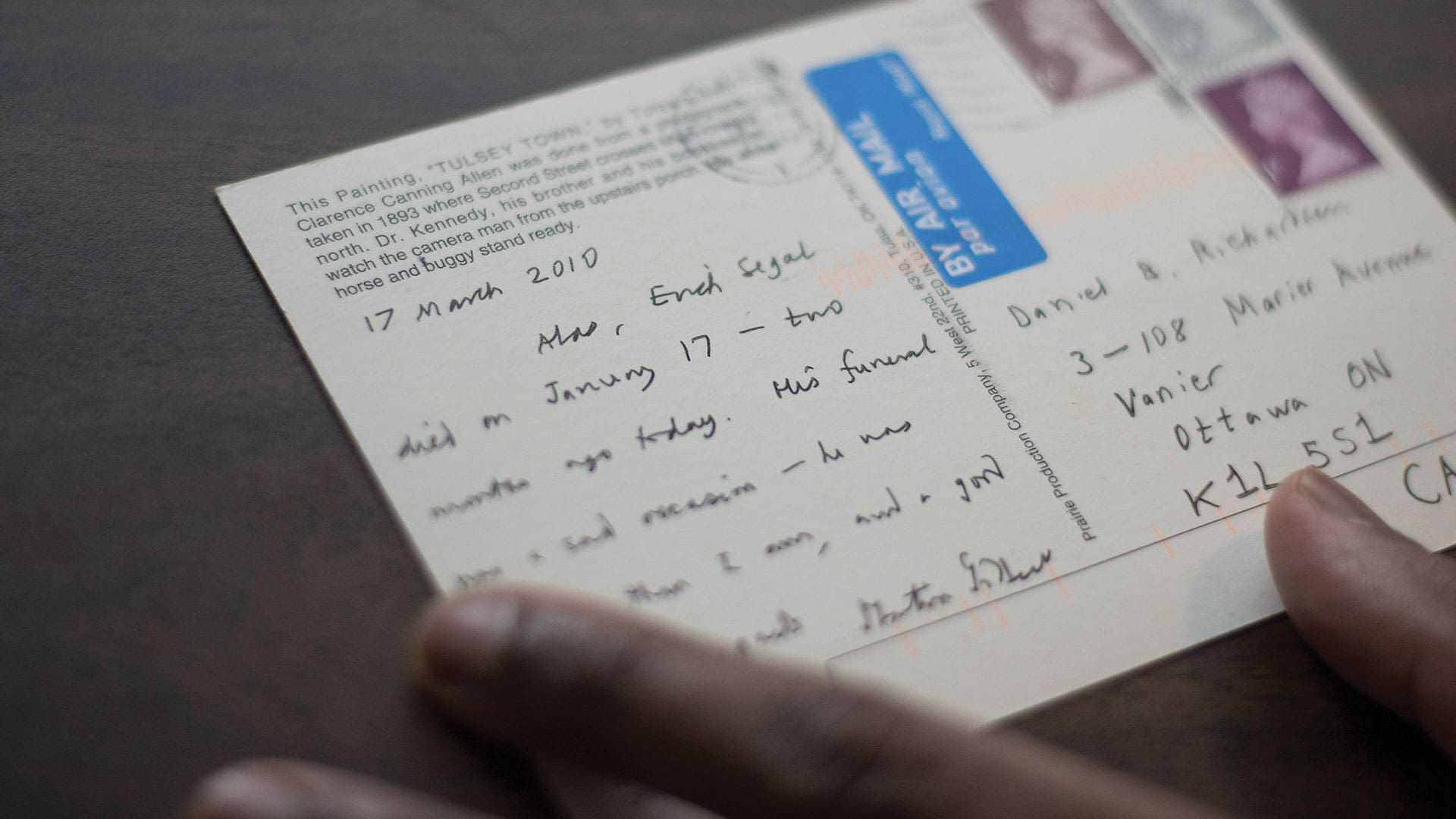

In my own life, I have been surprised by magnanimity. I never met Sir Martin Gilbert—Winston Churchill’s official biographer and one of the greatest chroniclers of the twentieth century—in person. An email exchange between us developed into written correspondence, and he even chose to pass on a letter to the writer Erich Segal, a friend of his, and someone whose novels I’d thoroughly enjoyed. Segal was dying and managed to respond to me in his final months. This postcard, one of several I received before Sir Martin’s own death, was written a couple months after Segal’s funeral. I’m still stunned that these men whom I admired not only heard from me but also took the time to convey far more than perfunctory platitudes in return. I’m reminded that even in my depraved tendency to judge someone as not worth my time or attention, true friendship—understood as a path to greater maturity as a human being—requires the practice of a more impartial generosity, rooted in seeing the divine image etched in each person.

I still struggle with friendships that end. Not ones that are simply paused or in abeyance and so could be picked up easily with nary an ill-effect. I mean the ones that were once close and intimate but have long since ceased to be. And the ones with people who, for varying reasons, it would be inappropriate or impossible to get back in touch with. The postcards in this photo represent the phantoms of once-close friendships with those who (I presume) are still living but are no longer in my orbit, nor I in theirs. Though a sense of loyalty might attempt to force them to continue, for different mysterious and natural reasons certain friendships last only for a season. And while some effort is warranted, it is also important to relinquish control and surrender to the wishes of another or to the facts of circumstance. I’m discovering that this posture toward friendship is closer to the Christian understanding of God’s patient and uncoercive wooing of our hearts and selves, of a God who leaves us to our freedom of not having him in the field of our vision, and thinking (falsely) that we are not in his. I’m learning to mean the phrase “Fare thee well” even to these others in my life and be at peace.

A few months ago, I received the shocking news that a childhood friend had suddenly died while he was visiting his family. It was particularly heartbreaking for me because we had lost touch, not out of any falling out or lack of interest in each others’ lives, but because of the simple inertia caused by different lives in different time zones. There is an imagined pressure I’ve felt to get a faraway friend up to speed in a comprehensive way, thinking that this didactic monologue would act as a glue to make up for the unshared life. Even thinking of doing so is exhausting, especially when it requires repeating the same details to multiple others, so some calls never get made. How foolish. In true friendships, no milestones need to be achieved in order to garner a reason to get in touch. To my regret, in this friend’s case, it was too late. Since so many of our close memories happened during an era when there were no smartphones, I realized I could not even locate photos of us together. All I have are empty hands, which are not sufficient. I’m reminded that even what seem like robust mementos can and will fade. I’m consoled in the hope that it is God who can re-member us, put us together again with all that seems fleeting or lost, both here and in the kingdom without end.

Companionship Toward Destiny

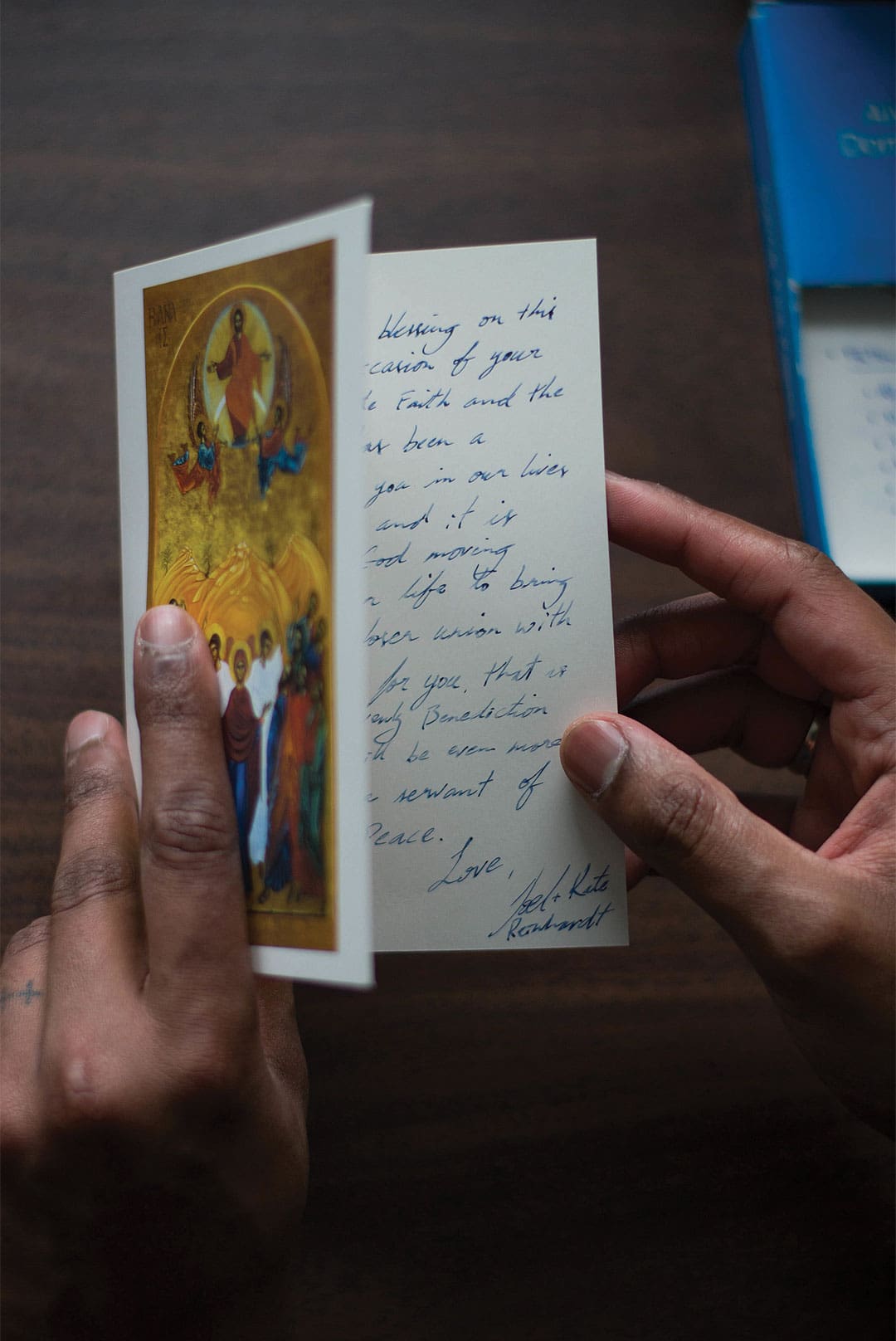

A beguiling description of friendship is one in which the task is “helping each other have a truer gaze upon reality.” This definition comes from Julián Carrón’s book Disarming Beauty. The reality it describes includes the transcendent and the banal. The card in this image was given to me by friends who are a married couple. They gave it to me during my confirmation. Even though they did not share the specific Christian tradition into which I was being confirmed, their note expressed genuine delight at the development of my spiritual itinerary. If our common destiny is toward wholeness, holiness, and a union with God, then true friendship affords the companionship on a path, the path of our lives, helping us take our desires and our questions seriously, and pointing us toward someone greater than ourselves. Perhaps the truest help of friendship is those whose presence helps make our burdens a little lighter, and who re-present the companionship and consolation of God.