O

One of the most troubling developments in American life in the last fifteen years is the rise of a new, virulent mutation of a very old practice: cancelling. Countless individuals have lost jobs, reputations, friends, loved ones, communities, and a sense of safe belonging in their world.

Many people, especially those on the young left, have defended cancelling as a punishment befitting a range of social crimes. “Cancel culture is the best weapon the powerless possess,” roared a headline in the Daily Beast, arguing that cancellation is a way for the marginalized to strike back against the powerful. “Cancel culture is the only option left when institutions fail and powerful individuals run amuck,” wrote the article’s author, Ernest Owens. “The court of public opinion can outweigh everyone else when utilized effectively.”

Justified or not, from the cancelling of J.K. Rowling for objecting to the shifting of our understanding of women to “people who menstruate” to the growing blacklist of people who have lost their jobs for saying politically incorrect things on social media, cancellation leaves a wide swath of social destruction in its wake.

But why do people cancel? On one level, the answer is obvious: the impulse to forcibly silence our opponents is as instinctive as the tendency to rubberneck when passing a crime scene. “Shut up!” we say when we feel put upon. But as a cultural trend that’s seeped into every part of our public rhetoric and political consciousness, surely there’s something deeper at play than simple vented spleen.

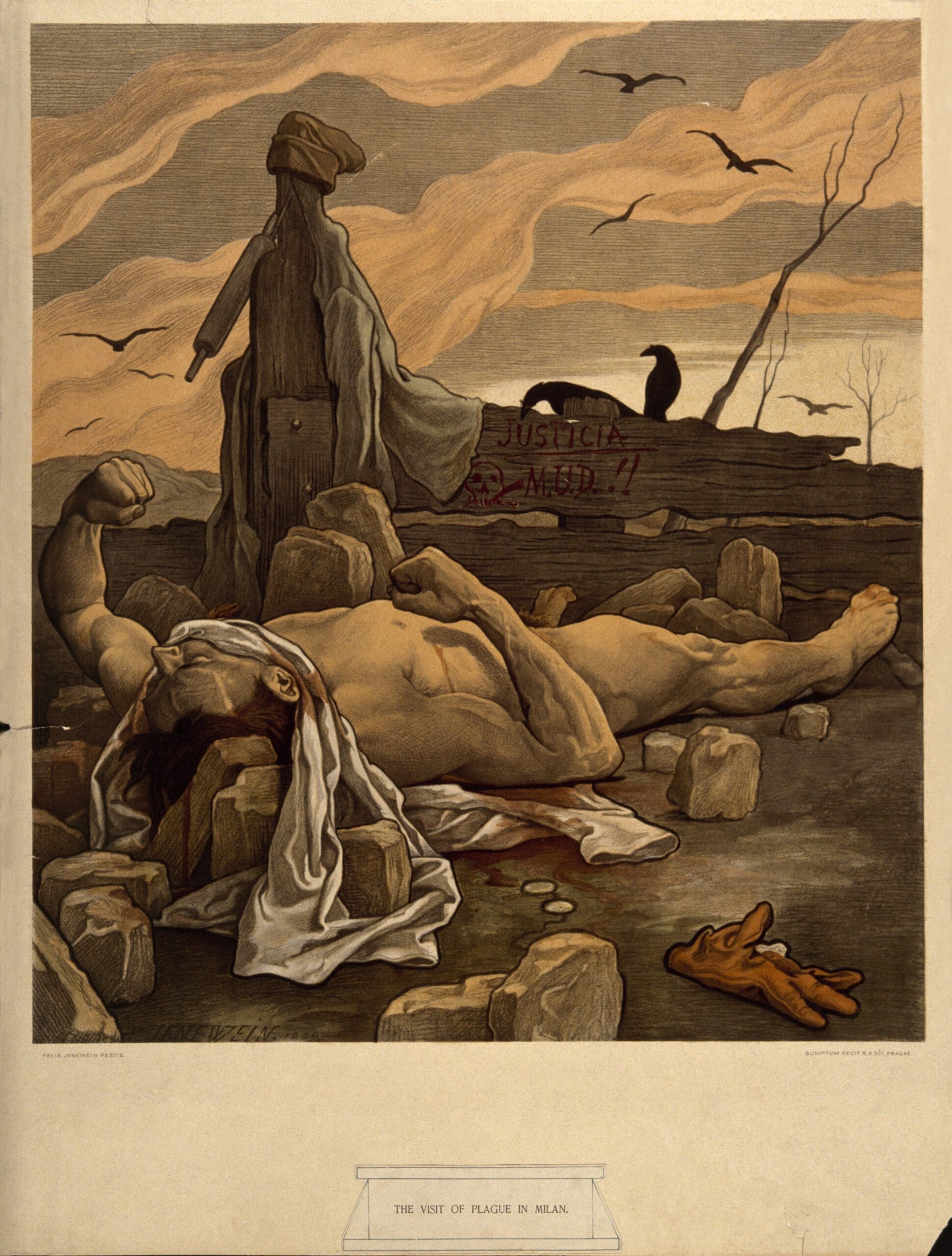

Let’s start with the central force driving the phenomenon of cancel culture: the challenge of social change. Our forefathers and mothers fought the opening battles and in many cases the most physically brutal phases of today’s social movements. They were the ones plastered by firehoses and gunned down by bullets. They were the ones who endured beatings and imprisonment, who were reduced to hunger strikes as their last remaining tool for achieving foundational legal victories. Some of that character remains in today’s social struggles, but more often the risks pertain to positions a little higher on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: employment, reputation, belonging—every variety of social ostracism. The human heart is the new battleground, and it is amorphous, intense, deceitful, and radioactive.

In keeping with this less visible field of war, today’s racism and sexism are typically more subtle than in times past. Few people will explicitly defend racial or sexual bias now, but the beliefs beneath them remain. There are statutes that outlaw sexual harassment, but women who sue their employers still find it harder to get the next job than those who leave quietly. People of colour who complain about mistreatment based on race find their cases devilishly tricky to prove and can suffer reputational damage for years.

When we zoom out from the realm of individual actions and look at broader outcomes, we see plain evidence for the persistence of discrimination. Banks reject black Americans for home loans at far higher rates, even when controlling for all other factors. Police arrest black Americans at far higher rates, even controlling for the prevalence of crime. Women make less money than men, even controlling for decisions about child-bearing. Most chillingly, the lifespan of black men is six years lower than their white counterparts. It’s hard to clean out the foundation.

But wait, you say, that’s all well and good: social change is hard and cultures change slowly, but why does that justify excommunicating someone who uses the wrong pronouns?

There are three answers to this question. The first involves an unpleasant combo of emotional intensity and powerlessness. When you’ve experienced enough trauma, enough degradation, and enough alienation, at some point you become impatient with nuance and you just want to make it stop. You want to take power away from those whose words and worldviews lead to real damage to your person and your life, and without formal economic or legal tools at your disposal, you use the tools of culture—the court of public opinion.

Second, the tools of culture are very effective. The strategy of using social norms to control problematic behaviour and suppress problematic beliefs is powerful and fast-acting. We know that people respond intensely to social cues, even about small behaviours, and when you invoke the threat of full-on public humiliation, most people will come to heel. What the activist left is doing in America today is trying to force social norms to shift faster than they usually do, and they’re pursuing their agenda with a “you have to break a few eggs to make an omelet” zeal, fairly indifferent to the so-called bigots who suffer as a result.

The third answer is more controversial: words really do matter. It’s easy to mock student snowflakes who equate misgendering with assault, but under the right conditions, words really can constitute a type of violence. That’s because we have a culture of violence—and by “we” I don’t mean the West alone; I mean all of humanity. And that culture is codified through words as well as deeds.

There is a difference between a threat and a bullet. But a deeper understanding places them at different points along the same spectrum rather than as things completely different in kind.

Every culture has codes that dictate when and how violence is sanctioned—when we give permission to inflict bodily harm, by whom, how much, and what kind. Those codes are reified and enforced by words, words that enable, forbid, honour, shame, inflame, or circumscribe violent acts. One cannot understand the rampant sexual abuse in this country without notions like “boys will be boys,” “everyone had been drinking,” “she was asking for it,” “she sent mixed signals,” or—to take one of many horrifying “jokes” that were common within living memory—“if you’re going to be raped, you might as well lie back and enjoy it.”

Some of the phrases I just used are offensive to today’s sensibilities (no one would advise enjoying rape); others are not (if everyone has been drinking, is it fair to hold just the man accountable?). Together, they constitute a series of ideas that express different aspects of our code of violence when it comes to sex. All these phrases have been understood as appropriate, or at least tolerable, comments at different times in the last century and in different parts of America. The listener’s comfort level with these phrases reflects our deeply ingrained understanding of what constitutes sexual violence and when certain acts are acceptable. Those understandings directly affect whether and when a woman has to worry about being in the presence of a man without other people in the room—because they affect the understandings that man might have in his mind about sexual violence, and when he’s permitted to engage in it. Relatedly, the understandings of their shared community affect whether a man feels he’s likely to be punished or affirmed if he does certain things, and whether the woman will be supported or ostracized if she complains.

Our bodies hold these codes deep down, in the parts of us that instinctively assess danger and safety. Is it so strange, then, that the expression of beliefs that are highly correlated with dangerous action—especially when affirmed by the larger community—can cause one’s body to perceive danger? When people say, “That statement makes me feel unsafe,” they are making a claim to certain rights, but they’re also offering an accurate description of the unconscious effect certain words can produce. Bodies feel unsafe when they encounter stimuli they associate with danger. Is it such a stretch to say that loudly asserting acceptance of physical violence—say, by calling for the cleansing of a group or, more subtly, declaring that boys will be boys and therefore there’s nothing we can do about their sexual proclivities—is on the spectrum of violence too?

My argument is emphatically not that physical violence and dangerous words are the same. There is a difference between a threat and a bullet. But a deeper understanding places them at different points along the same spectrum rather than as things completely different in kind.

Now, add to this the distinctive epistemology of postmodern Gen Z life, in which truth primarily comes from felt experience and can be questioned only from within that frame, and it’s easy to see how we get from an individual’s assertion that “this sentence makes me feel unsafe; it feels violent to me” to treating that felt reality as objective fact, and acting on it to sanction the person who spoke that sentence as though they committed physical violence.

Let’s talk about that sanctioning for a moment. When people commit acts of physical violence, we don’t torture or kill them (usually); what we do is take away their power. We lock them up and make it so that they do not have the ability to perpetrate physical violence against the innocent again, at least for a time. And the assessment of that time period reflects a strong emphasis on the punishment being proportional to the crime. But it wasn’t always that way. For centuries, punishment was determined by authoritarian arrogance or mob-fuelled frenzy, forces that radically escalate the severity of punishments. Recently, we have built sophisticated, if flawed, institutions founded on an understanding of justice that prizes proportionality to mete out less excessive but still punishing consequences.

Unfortunately, another feature of Gen Z life is a radical distrust of institutions. Most Gen Z individuals I’ve spoken with have told me they don’t believe institutions will act on their values, and polling data bears out that skepticism. Barely a third of young people have a lot or a great deal of trust in the police, and even fewer in the criminal justice system. Congress, tech companies, and the media fare even worse.

So instead of relying on institutions to live up to their commitments, members of Gen Z feel responsible for enforcing their values on institutions. Hearing this, it can be tempting to look down one’s nose at the Young Turks and chastise them for insufficient humility, but there’s another lens that strikes me as legitimate. Think of what it must feel like to believe that you are alone in society, without the strength of institutions protecting you and the things that matter to you. Gen Z has been told that it has power, and that if a wrong is happening, well, no outside help is coming. It is up to the individual, or the collective action of individuals, to make things right. That is a heavy burden. Combine this with the vigilance palpable on nearly every college campus I’ve visited, the fear that if you don’t say and do the right things, you will be the next one offered up at the Instagram altar, the next scrollable sacrifice, and you have a recipe for excess.

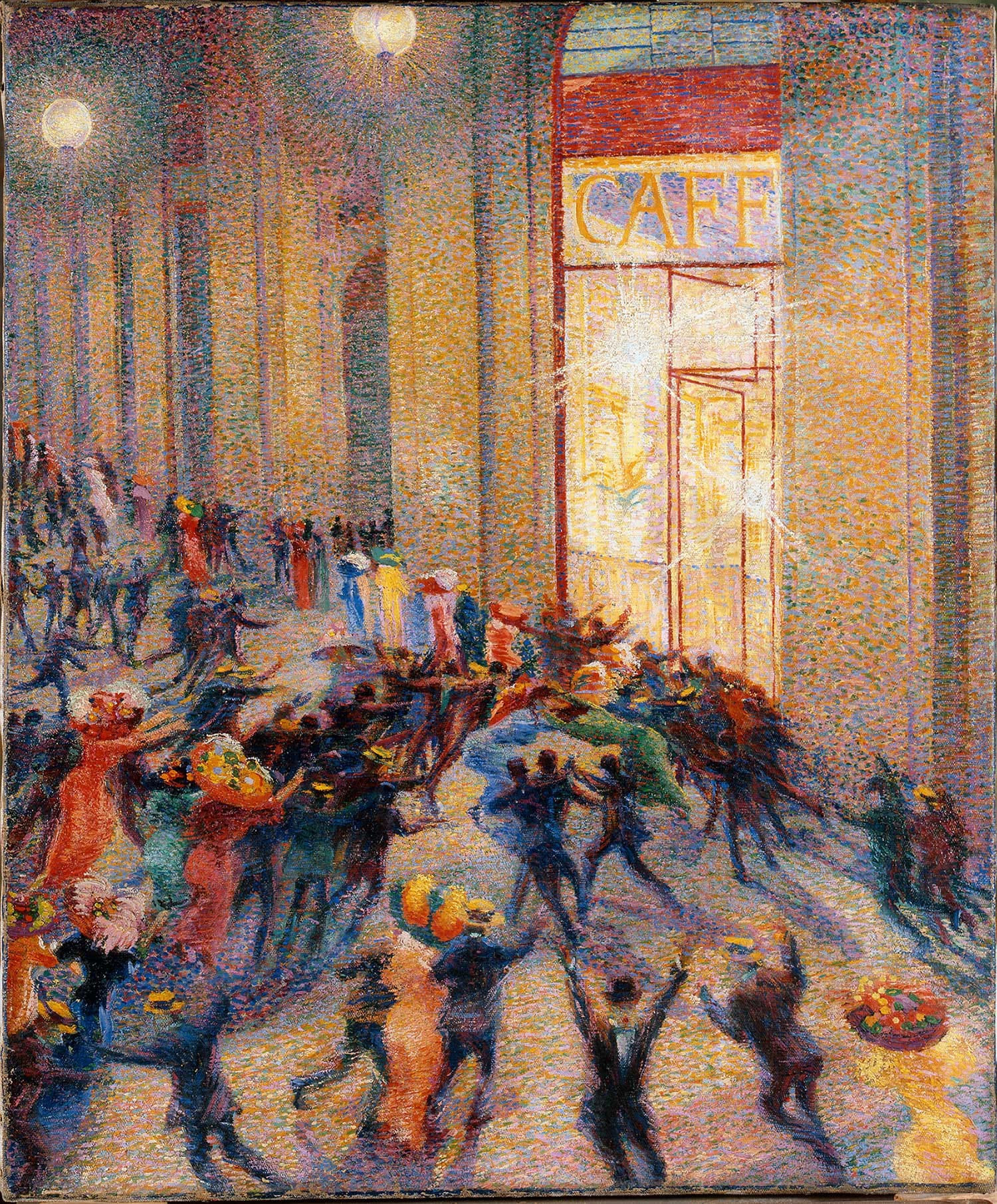

In this logic, if someone has committed a social crime, in the form of expressing something beyond the bounds of our codes, they merit a social punishment, some kind of proportional social sanction that takes away power from the offender. All morally coherent so far. The problem is that as the understanding of words-as-violence has intensified—as young people especially view threatening rhetoric as a liability on par with threatening action—the sense of appropriately severe sanctions has escalated in turn. Add to this the pervasive insecurity generated by distrust in institutions, and the mob dynamics literally coded into the structure of social media, and it’s no surprise that we are now in an almost reflexive posture of what could be called social capital punishment: cancelling, the modern-day stoning.

It’s how you get a situation where an academic administrator’s take on Halloween costumes is read as a powerful threat to the safety and belonging of minority students, justifying a frenzied (and successful) effort at getting that person removed from power. It’s how you get New York Times employees declaring, with apparent sincerity, that an editor put their lives at risk by running a controversial op-ed.

Cancellation is indeed a social phenomenon, a feature of our politics and public life to be studied and measured. But it is also deeply personal. It is relational: these excesses don’t just overstep in a logical way; they rip apart communities, friendships, family ties. It’s one thing to say words can be violent, but it’s another to tell your grandfather that you’re severing the relationship because of his failure to reckon with structural racism.

To understand something so intimate, we must plumb the inner workings of our own relationship to sin: how this feels, not just how it looks.

Start with the impulse toward purity. We all want to be good, all the way through. It feels exquisite to be in spaces, communities, and times where we feel that we are good. We have excised the evil, disciplined ourselves to turn from sin, and it feels liberating, even exhilarating.

The problem is that this is an illusion. As much as we want to be good, we are all somehow trapped in human lives in which we will also, at times, be evil. But human evil is so ugly, so wretched, that when we see it in ourselves, we want to rip it out, cast it away, find some way to rid ourselves of its filth. And so we find ways to believe the illusion that we are good, and engage in rituals to cleanse ourselves of impurities. In biblical times, communities symbolically placed all their sin on a goat, which was then sacrificed or allowed to run away—the origin of the term “scapegoat.” Today, we buy carbon offsets, eat ethically, perform land acknowledgements, and eagerly send one another social media clips of offensive things that have happened, then affirm for one another that none of us are like “them”—either the perpetrator or the victim.

Turning off empathy is not actually very hard for a human being; it takes a major counterweight to elicit anything different.

The temptation to purify, to act righteously against evil, is so strong that even if it’s your grandfather on the other side, even if it’s your best friend, if they show themselves to be on the side of evil—be it racism, sexism, heteronormativity, religious heresy, or political correctness—you will often choose loyalty to “the good” and excise that person as one more branch that needed to be pruned.

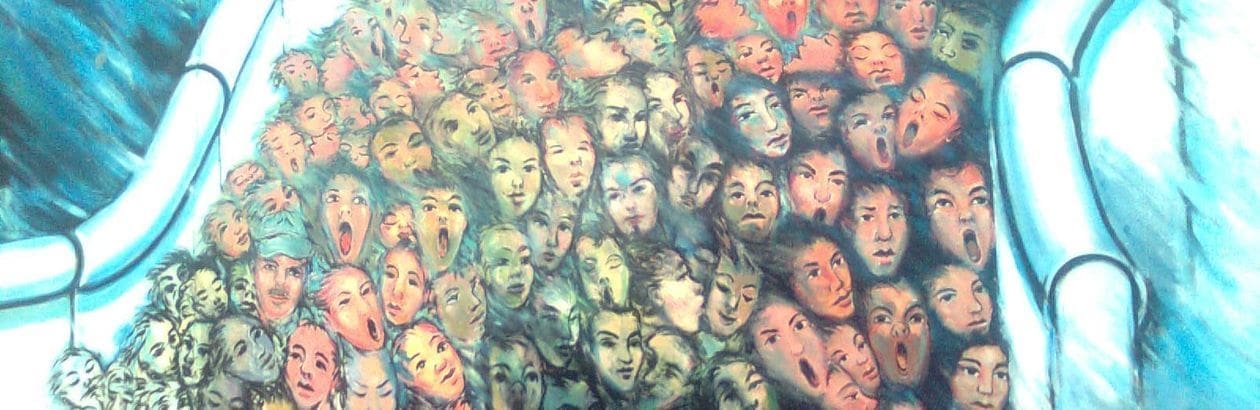

But it’s inhuman, you say. How can people callous themselves so far as to cut off relationship? One answer is structural: thanks to the internet and various types of self-segregation, we no longer regularly encounter people on the other side of our basic beliefs, so they are easier to hate. The deeper answer is anthropological: turning off empathy is not actually very hard for a human being; it takes a major counterweight to elicit anything different.

For some people, silencing is natural because they’ve already tasted it. When you’ve been made voiceless, when you have been a victim of silencing firsthand, it makes intuitive sense to you to respond in kind. It’s an eye for an eye, yes—we’d be lying if we denied that there’s some satisfaction in the retributive justice of it—but more importantly, it’s simply the language and toolkit that feels familiar. We naturally jump to the modes of social sanction and redress that we have encountered in the past, unless we feel quite safe in our social setting.

For those of us who haven’t been silenced, it is tempting to be an “ally,” to fight on behalf of those who have been victimized. It’s difficult, in that position, not to feel righteous, and righteousness can easily blind us to the consequences of our actions. And even if you don’t consider yourself an ally, in a climate of fear, mob frenzies flourish. When you’re vigilant all the time, waiting for the mob, trying to make sure you don’t prick the mob, then when a mob finally forms, you grab your pitchfork and surge out into the street too. You’re just glad to have a chance to release all that pent-up aggression and fear.

Is silencing violent? Yes, but violence is natural to us. Cancelling represents an old form of justice, an eye for an eye, unmediated by institutions that counterbalance our baser instincts. It’s less surprising that it’s here than that we are surprised. The anomaly lies in our expectations: we live in a society quite different from most societies in human history, one in which we expect violence to be restrained and to some degree civilized.

But we haven’t yet had time to develop norms that can effectively civilize social media. Simultaneously, the need to deal with structural sin feels urgent to many people, and how can we blame them? How long should women have to wait for a world where they are not likely to be assaulted? Shouldn’t we be willing to tolerate significant instability to finally make African American life equal in this country? So we’re defaulting to “an eye for an eye.” The real question is, In the decades before institutions can give us the tools we really need to see a more perfect justice, how do we deal with human sin?

One glimmer of hope lies in the communities that are healthy. Most of us still have small pockets of our lives where we feel really safe, where asking open and socially risky questions feels interesting, not dangerous. It is entirely possible to create a circle of people, even a whole organization, where generous treatment of those who transgress social lines—at least with regard to their intentions, if not their actual behaviours—is the expectation. These communities contain in seed form the norms that, if codified, could create a much healthier society. Unfortunately, these are a small minority of communities, and they are ephemeral without the structured backbone of the institutions that we will, hopefully, someday see.

The deeper answer to this puzzle lies not in our current approach but in what is missing from that approach. Rupture of relationship—even relational cutoff—is ordinary; what’s extraordinary is that we sometimes commit deeply to never saying “I will never speak to you again,” leaving an opening for relationship. The truth is, of course, that we can’t throw people away and survive it. We can’t purge our own sin, but we need some way to deal with our moral horror at ourselves and at the world.

The answer to this human question is old. We need a community and a framework that remind us over and over again that the line between good and evil runs down every human heart—including our own. That belief has to be deeply ingrained and constantly refreshed, because it is so tempting to believe we are the good ones. Mainstream American culture still has a core belief that “we all make mistakes” and “nobody’s perfect,” but that isn’t deep enough. We need something more akin to the Christian concept of sin, because people have to believe in their bones that the person they’re staring at on the other side of the line who has committed wrong, the person they are about to excommunicate, has done something that we ourselves could just as easily have done.

Without this conviction, we run afoul of Martin Luther King Jr.’s statement that “power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anemic.” We use power without love. Again, in the face of real suffering and wrong, the temptation to simplify is intense, so we need something strong enough to force us to hold the tension.

Christianity is the most powerful framework I know of for this. Among the great world traditions, it contains the most overt, radical expression of grace—that is, love offered in a moment when another’s behaviour doesn’t merit it. But it is by no means the only one. Buddhism’s lojong slogans express strikingly similar sentiments and would counsel that you cannot declare another person evil, because there are just people—not good ones and bad ones. New Age approaches emphasize that who you were yesterday need not be who you are tomorrow, and that each day offers another opportunity to be a different kind of person. American mythology, as well as that of many traditions around the world, is shot through with stories of redemption, hope, and renewal.

The real question is, In the decades before institutions can give us the tools we really need to see a more perfect justice, how do we deal with human sin?

These frameworks, in their best forms, would all counsel reacting to evil in a way that helps someone understand their bad action so that they can change. They would never counsel permanent exile. Though their language for it differs wildly, all recognize that each person is both broken and sacred, so cancelling should be off the table.

There is another step, beyond finding the right framework, that is even harder: we have to practice what it teaches. When the rubber meets the road and we’re facing decades or centuries of personal, excruciating pain, acting with love is truly radical. We have to be able to look someone in the eyes and say, “You’ve silenced me for generations; your narrative leads directly to my chains, to harm of my body, mind, and soul. You don’t know that and may not intend it—but then again, some part of you does. It’s probably subconscious, but human beings prefer positions of power to positions of equality; we feel safer. You may never acknowledge what you’ve done to me. I know all this. And I will still choose to be in relationship with you.”

That’s what it means to love.

The most powerful expression of this I’ve encountered in my own life was in the words of an African American pastor at Yale during one of the early campus race explosions, this one provoked by an email about Halloween costumes. When I asked him how he engaged his activist parishioners, he said the students came to him in tears, explaining how dehumanizing they found the exchanges with their peers on the other side. He comforted them and told them to stay and recover, and then said, essentially, “Then you’ve gotta go back out there.” Why, they asked? And he would answer, “Because they, too, are made in the image of God.”

Human beings are fallen. They will hurt you, over and over again. There are many roads to violence and pain, but only one to wholeness. And it is love. So come in and heal. Then go back out there and keep talking.