S

So long as New York has to tell you it’s back to its pre-Covid vitality, it evidently isn’t. For every cab driver who says things are going well, there are two who tell you otherwise. They blame the subway stabbings, the pot, or the phone-fixed pedestrians who won’t look up.

At least that’s what I learned on my way to that routine corralling of American artistic production we call the Whitney Biennial, from which one should never expect too much. Years ago at a previous biennial, as I dutifully listened to the curator’s tour, I realized that if I was playing a drinking game with the word “detritus,” I’d be dead.

Judging from the most high-profile assessments, 2024’s assemblage is uniformly unimpressive. If you ask the internet if the show is good, the algorithms default to Jerry Saltz’s Instagram, which explains it to be “a tepid affair, safe to the core and well-behaved, a good-looking, basically passionless, pleasureless look at a type of art that only curators could like.” Writing in the New York Times, Jason Farago calls it “resolutely low-risk, visually polite, and never letting the wrong image get in the way of the right position.” Another critic, Travis Diehl, regrets that the show “can’t seem to decide who or where its audience is, who needs to hear its message, or whether it should have a message at all.” Martha Schwendener, however, insists the message is unfortunately all too clear—namely, “you have to conform to distinct identity stereotypes rather than subvert them to succeed in the art world.”

Even a New Yorker critic who seeks to praise the show claims one of its lessons is that “twenty-first-century art can come from anywhere and still speak in the same jet-lagged monotone.” In an ingenious attempt to find something positive to say about the show, ARTnews maintains that if you find yourself—as so many have—unimpressed, that’s by design, more evidence for how defiant artists “decline to perform to the viewer’s liking.” Your dislike becomes evidence for artists refusing “to participate in structures that seek to oppress them.” At the same time, it’s the storied Whitney Biennial, the same cultural enterprise that helped launch Pollock, Dalí, O’Keeffe, and Rothko, so participating artists still get a convenient résumé boost. As the saying goes, it takes a century to ruin a name; and the first Whitney Biennial (back when it was an annual show) dates to 1932, so I guess there are still a few years left to run this enterprise into the ground.

Or so it seems. The show’s admission fee is too expensive for me to give up so soon. For anyone who remembers the old Whitney, the upside-down ziggurat known as the Breuer Building on 75th Street, the new Whitney is still a thrill, and the building and I are still enjoying our architectural honeymoon period. What was once a prison of confinement, with ungenerous window slits only stingily welcoming light, now opens on balcony after balcony of views usually enjoyed only by the rich. No matter how bad the art is, the skyline is always waiting, generously unfurling—cabby complaints notwithstanding—the festival of being we call New York.

As with each of the Whitney Biennials I’ve visited, traditional art forms sputteringly attempt to reassert themselves in 2024 as well. Eyeing the title of one series of adventurously abstract canvases, I realized I had never stopped to consider the copulation of whales (though a more direct term for this maritime union was employed). For the most part, however, instead of landscapes, the 2024 Biennial offers a variety of appeals to the indigenous populations of the earth to rescue us (though they are busy trying to survive themselves). Instead of sculptures of bodies, we get sculptures of body parts, such as Jes Fan’s fiberglass replicas of CT scans, or Julia Phillips’s hovering face and breasts pierced with medical tubing. There are lots of screens and stuff: screens displaying videos about historical atrocities or irreversible ecological collapse and stuff like a self-playing piano stripped of ivory that offers only muffled sounds, perhaps (if the above critics are to be trusted) a metaphor for the show itself.

A forest of screens by Isaac Julien re-enacts a conversation between collector Albert Barnes (discussed in this magazine before) and the Harlem Renaissance philosopher Alain Locke, with whom Barnes discussed the merits of African art (even if their friendship finally failed). African art, claimed Locke, survived “a period of neglect and disesteem” but is now “in danger of another sort of misconstruction, that of being taken up as an exotic fad and a fashionable amateurish interest.” To ask whether Locke’s insightful remark might apply to other things, like the fact that the 2024 Biennial’s “they/them” pronounces exceed its “he/him” pronouns, is of course utterly inappropriate, and I wouldn’t dare consider it. What I can’t help but consider is that the Barnes Foundation actually commissioned Julien’s piece, as if to buy itself a few more years before the looming threat of repatriation closes in. As African nations understandably demand their objects be returned from wealthy Western collections, a museum’s confession of colonial complicity is a clever method of retention. Julien’s work is an immersive success, combining tenderly shot sequences and close-ups of African objects with thoughtful commentary, but let’s also call this patronal strategy what it is: cancellation insurance.

Wearied (as was everyone else, judging from their facial expressions), I retreated to one of the balconies again to be refreshed by the views, but the art followed me. There I was faced with Ruins of Empire II, featuring a classical pediment of the White House made of dirt crested with an upside-down American flag. And then it hit me. Fortunately, as I reeled backward upon receiving this revelation, the balcony guardrails kept me from plummeting to an early demise. Indeed, to spell out the message I received from Ruins of Empire II in writing almost cheapens its oracular force, but I feel compelled to broadcast the message so that you, too, can benefit. That message was this: American democracy is not doing well. Thank you, art. Thank you, 2024 Whitney Biennial. You have proved your enduring, tax-exempt necessity. How could I possibly have learned this enduring lesson in any other way?

The Whitney Museum itself seems to invite such sarcasm. Kenneth Clark, who once defended the culture of what was then called civilization, is as extremely out of fashion today as an author can be. Yet, ironically enough, Ruins of Empire II proves Clark right:

Civilisation required a modicum of material prosperity—enough to provide a little leisure. But, far more, it requires confidence—confidence in the society in which one lives, belief in its philosophy, belief in its laws, and confidence in one’s own mental powers. . . . Vigorous, energy, vitality: all the great civilisations—or civilising epochs—have had a weight of energy behind them.

The 2024 Whitney Biennial confidently proclaims that we have no such confidence. When I re-entered the galleries after my balcony revelation, this message was delivered again and again. The subtitle of Karyn Olivier’s evocative sculpture of Mediterranean refuse simply asks, “How Many Ways Can You Disappear?” Olivier is referencing slavery, the refugee crisis, and maybe our civilization itself. Indeed, several of the artists in the show boast about the deliberate impermanence of their chosen materials, seeming to welcome the fact that their work is not long for this world.

Not the bad fear, mind you. Not the anti-choice, anti-trans, anti-vax, anti-immigrant kind of fear-mongering. The Whitney—rest assured—purveys the good kind of fear, which is to say, the fear about that kind of fear, which is perfectly okay, even required.

Anyway, the confidence Kenneth Clark once promoted, so the argument goes, is overrated. When societies do have confidence, they go around making other societies look just like them, and we, quite correctly, call that injustice. Hence the express aim of this year’s Biennial (and pretty much every other well-funded academic and cultural enterprise of late) is to point to the “long history of deeming people of marginalized race, gender, and ability as less than real.”

It would not be unfair to conclude that the 2024 Whitney Biennial runs on fear. But not the bad fear, mind you. Not the anti-choice, anti-trans, anti-vax, anti-immigrant kind of fear-mongering. The Whitney—rest assured—purveys the good kind of fear, which is to say, the fear about that kind of fear, which is perfectly okay, even required. In fact—the Whitney Biennial tells us—if you want to participate in the American art world, this good kind of fear is the ticket price. Good fear (if the show’s official literature is to be taken at face value) is fear of political forces that “perpetuate transphobia and restrict body autonomy in the United States.”

The established critics I began with smell the fear as well, identifying a political straitjacket that every artist and critic is expected to wear. Returning to Farago’s analysis:

Artists emerging today are intelligent but terrified. Exhausted by culture’s surrender to the market, badly outmatched by Silicon Valley’s image regimes, they conclude that small-scale (and museum-compliant) acts of demonstration and recalcitrance are the safest bet. . . . We have all the answers already: Cannupa Hanska Luger abstracts a tipi from recycled fabrics and hangs it upside down, a distress signal from the world colonialism made (and you, if you find it obvious, are a bullheaded settler). Carmen Winant pastes to the wall snapshots of physicians and volunteers at abortion providers and women’s health clinics (and you, if you find the accumulation as formless as a social feed, are guilty of minimizing threats to women’s health).

In short, these three abide at the 2024 Whitney Biennial: decolonization, absolute body autonomy, and fear. But the greatest of these is fear.

These three abide at the 2024 Whitney Biennial: decolonization, absolute body autonomy, and fear. But the greatest of these is fear.

Fortunately during my visit, the Biennial did offer an out, even if it might be called a cultural form of physician-assisted suicide. I wandered into a separate exhibition featuring the early innovators of automated art, whose programming name was AARON. After all, if we—like the timid Moses deferring to his brother—refuse to enact the cultural-making mandate ourselves, why not let our fraternal computers do it for us? The exhibition showed robots making early sketches and told the history of what has now become the looming threat to human creativity we know as artificial intelligence. This was the one room in the museum, on my visit at least, where real excitement from the audience could be sensed. Chattering crowds were gathered around each of the busy machines.

There I felt new sympathy for what came over critics like Arthur Danto, who at the end of the last century tidily proclaimed the “end of art.” The story of art is unwieldy and inchoate, and critics need to assign contours, which is partly why Danto found the pop art of Andy Warhol to be the art train’s final station, where the art market merged with the supermarket. Now with AI art, I supposed I could find my own end to the story as well, one even more terminal than Warhol’s Brillo boxes. Who killed art? Artificial intelligence did, with the art of the unimpressive 2024 Whitney Biennial a willing accomplice in its own demise.

Who killed art? Artificial intelligence did, with the art of the unimpressive 2024 Whitney Biennial a willing accomplice in its own demise.

But just before I could pull the plug on art with this new pet theory of mine, I decided to give the exhibition another go. I took in the top-floor view to fortify myself, entered the galleries, and pulled the one-armed bandit of artistic production a final time, and—to my surprise—hit triple sevens. The payoff came as I looked out of the exhibition’s windows, a window that (it turns out) reflected a cleverly concealed neon message about Palestinian liberation. There, after a silent prayer for an end to the Holy Land’s agonizing strife, a prayer irreducible to a partisan slogan, I saw something genuinely hopeful. Namely, the art outside the museum itself. What I saw in the distance was Little Island, an unalloyed triumph of landscape architecture, and so I hastily made my escape.

The word “developed” has taken on sinister connotations in urban planning, signifying paved paradises or tracts of wilderness macerated by uninspired subdivisions. But Little Island has developed the West Side of Manhattan in the best imaginable sense. As I approached the concrete lily pads of this artificial peninsula, I saw unguarded pleasure on people’s faces, pleasure that I had not seen since Christo’s Central Park Installation, The Gates, in 2005. Little Island passed the most important art test I know of—the kid test. All the children were delighted, and they summoned childlike delight from their accompanying adults. I even saw the very same faces that had grimaced from the predictable messages of the 2024 Whitney Biennial surrendering to unaffected smiles as they enjoyed Little Island’s accessible public art. I guess I wasn’t the only one who escaped. So I kept walking.

As I made my way up the High Line, that reclaimed railway that hovers above the Chelsea gallery district, I beheld more public art that awakened childlike wonder in adults. The High Line has expanded with new installations, new murals, new viewing points, and new gardens since my last visit. All of these are framed by wonderfully bulbous postmodern apartment buildings that are still enjoying the end of modernity’s straight-line regime. One sculpture, Benjamin Von Wong’s Single Use Reflections, was a pile of repurposed trash and mirrors. It was crawling with delighted parents and children using the sculpture to hide and exchange messages, which could be whispered through its tubes. Only later did I realize the sculpture was delivering an environmentalist message about recycling; the piece was pleasing enough as a sculpture that I was even inclined to listen.

So I kept walking. I passed determined outdoor curators and landscape architects who were keeping this public space managed and clean. I crossed over a raised wooden bridge that ushers pedestrians into further expanses of the city, and there the curmudgeon in me met his kryptonite. Those who still grumble about the destruction of old Penn Station are now faced with the realized dream of its redemption, the Moynihan Train Hall, whose sunlit interior at last rewards the patrons of rail. The expansively elegant space nearly equals the splendour of its foolishly demolished predecessor. Exiting the precinct, I looked up and saw a piece of public art by Elmgreen & Dragset titled The Hive (2020). The sculpture replicated buildings not only from New York but from Chicago, Paris, and London as well.

The higher these skyscrapers—or, better, groundscrapers—reached, the closer they came to the earth. It was a beautiful race to the bottom. The piece almost seemed to suggest that humanity’s highest ambition might be to serve. Perhaps “civilization” need not be about becoming higher, better, and stronger but rather kinder, nimbler, and steadier. Here was that crumbling dirt White House of the 2024 Biennial, with its upside-down flag, but without the defeatism. Maybe, critical cynicism notwithstanding, there is something to Cannupa Hanska Luger’s inverted teepee after all. The artist herself explains, “This installation is not inverted . . . our current world is upside down.” Or, as another artist even more assertively once put it, “Every valley shall be raised up, every mountain and hill made low” (Isaiah 40:4).

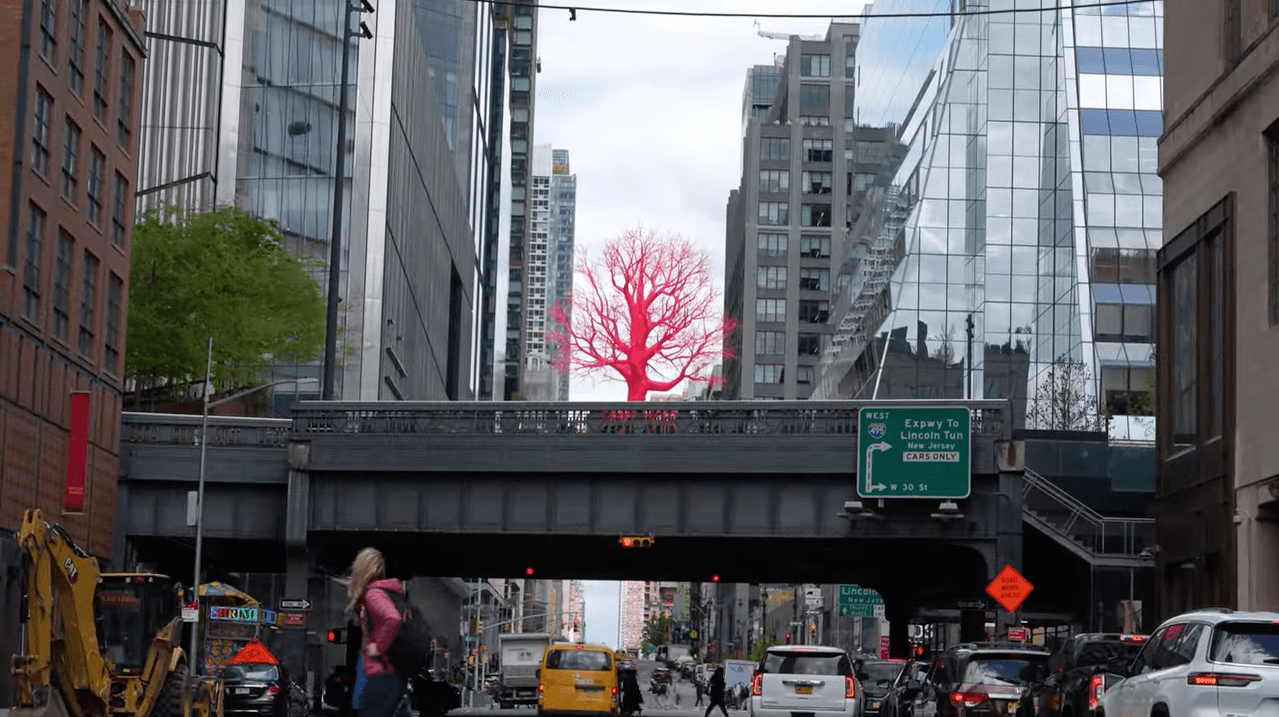

So I kept walking, doubling back toward the High Line. Unlike the curators at the Whitney, the confident managers of the High Line’s public art are fearless. With each sprout of native plants, graceful greenery, and accessible art that brought a once-dead part of the city back to life, I found my sense of American cultural confidence restored. Then, amid the jubilant foliage, came a plant I did not recognize. Ahead of me, I beheld a neon pink tree of life floating above Tenth Avenue, as if from a quickening dream. Swiss artist Pamela Rosenkranz’s Old Tree was like stepping into an illustrated version of the Upanishads or a simulation of Genesis’s tree of life. This is public art worth talking about. It is not political; it is not preachy. It is mythic.

This is public art worth talking about. It is not political; it is not preachy. It is mythic.

The new public art of New York’s Lower West Side is so good, in fact, that it caused me to go back to the Biennial that I had just left. There I discovered what I could not see at first. It turns out painting is in fact on full display in the Biennial; I had just not offered it sufficient attention. Maja Ruznic, for example, offered what appeared to be a Rothko painting, though one lovingly inhabited by a solitary figure. Her work rehearses the gentle return of the human after abstraction since the middle of the century past—and the return of spirituality as well. The Whitney’s scholars make a well-researched claim that her work is pagan, but I wonder if they also caught the titular reference to Psalm 42:7, Deep Calls Unto Deep. And the reference, make no mistake, is deliberate. Divinity, religion, and spirituality are the first things that come up in an interview with the artist. Raised by a mother fearful of religion, Ruznic finds herself returning to it nonetheless, albeit in a Dionysian, apophatic hue. The figure’s warped legs, protruding in the wrong direction, suggest someone who has forgotten how to pray, but who desperately wants to remember.

Looking again, I realized the 2024 Biennial does allow itself repeated moments of unguarded beauty, as when the aforementioned conglomeration of stuff becomes translucent or evocative or unrecognizable through a fusion of traditional media, whether in Suzanne Jackson’s abstract sculpture-paintings or Lotus Kang’s immersive strips that are photographs, drawings, installations, and sculptures at once. If the only trustworthy definition of beauty (as I see it) escapes all constraints of definition, should we be surprised when the constraints of classical media are exceeded as well? Kang’s ribbons of exposed film hang over the exhibition like clerical vestments. Their literal development over the course of the exhibition reminds us to never trust a theory of beauty that is set.

And how could I have missed Harmony Hammond’s Black Cross #1, which might even be considered the key to the show? As a southwestern artist, Hammond is obviously aware of the same cross motif deployed by Georgia O’Keeffe. When O’Keeffe’s New Mexico paintings were first exhibited in New York, critics like Marty Mann saw “a certain unpleasant hysteria in her mystic crosses.” Henry McBride cackled in the New York Sun that “O’Keeffe got religion.” But O’Keeffe was undeterred, and, so it seems, is Hammond. The four central dots in O’Keeffe’s famous painting are reasserted in the background of Hammond’s, replicating and refreshing the message.

Hammond, now eighty, tethers every imaginable art-world-approved political opinion on her crosses (as we’ve seen, this is required), but I’m not sure I buy the explanations. To misquote Sigmund Freud, sometimes a cross is just a cross, welcoming—not childishly refusing—the ample pain of the world. Ruminating on Hammond’s extracurricular expansion of O’Keeffe’s cruciform pattern, I think of the Irish poet Joseph Mary Plunkett, executed for his role in the 1916 Easter Rising: “His crown of thorns is twined with every thorn, His cross is every tree.”

What is more, if you look closely enough, the centre of Hammond’s gorgeously tactile cross almost seems to be a door waiting to be opened, even if opening that door would feel like prematurely pulling dressing off freshly wounded skin. For Harmony Hammond, the gateway to lasting redemption has yet to be opened; just as for Tomáš Halík, the difference between atheism and faith is patience with God. For this viewer at least, Hammond’s cross promises there is an alternative order, one that both the custodians and the critics of “civilization” have missed. But—considering the art establishment’s evident fatigue—it also resolutely proclaims, “And don’t expect to find that order at the Whitney Biennial!”

The beauty in the Biennial—like a bellflower breaching the blacktop—is all the more impressive for existing despite the show’s dreary political demands.

And then it hit me, but for real this time. An actual revelation. Fear may kill creativity, but love—from curators to creators to critics—casts it out. America may be in political free fall, but Rosenkranz still made that pink tree. The beauty in the Biennial—like a bellflower breaching the blacktop—is all the more impressive for existing despite the show’s dreary political demands. The crosses of Chelsea’s neighbourhood churches and Hammond’s cross within the Biennial might not be as disconnected as we think. Life is too short to hate the Whitney Biennial, and we don’t have to. If we perform an emergency dilation to include the rest of Manhattan’s West Side art in the show, it almost works.

Maybe New York actually is back to pre-Covid vitality, with global refugees from horrific conflicts entering its precincts today just as they did when Ellis Island was operating full tilt. They don’t have time for the complaints by the Biennial or about it. They know it is still a gift to live in a country that you can openly criticize without being routinely arrested or killed. No one wins if New York is not healthy, and parts of this city most certainly are. Every person in whom the candle of kindness is still burning can still grant New York—and each of its artists, especially the terrified ones—a share of our most threatened currency. Attention is just another name for love.