I

I’ve often said to close friends—probably too casually—that divorce is harder than cancer. Here is what I mean.

I was married to Don, the love of my life, for thirteen years. We had two young children and had built a life of goodness, chores, spontaneity, challenging days, a vast circle of friends, and what I thought was a deep anchor of gratitude for living out so many of our ideals. Our home was in Seattle, in a house on the Magnolia bluff, with a view of Elliott Bay. Occasional tourist buses would circle our neighbourhood to get one of the city’s proudest views of the water. I sometimes passed those buses as I jogged along a path looking over the sea. Should anyone live in a neighbourhood that tourists like to visit? Whenever this thought hit me, I would stop to walk: How does gratitude sit close to passing guilt?

Comparing pain is a fool’s errand. Some divorces can yield a rebirth, and some cancers can be lived with as a chronic disease or even overcome. But in my story I had extremes of both. On a grey and wet January morning, I discovered what no spouse should ever see: hundreds of emails and photos on Don’s phone revealing that he had created a double life with a mistress who lived hundreds of miles away. Six years after that awful discovery—now a single mom living in Silicon Valley and moving out of a season of recovery and into rebuilding—I learned I had stage IV metastatic colon cancer. The odds of surviving five years are 14 percent. How could my story hold both traumas?

To be more precise, this was our story. Our kids—Connor and Lucy—were elementary students when I told them the news that our family would be forever broken. They were sixteen and fourteen when I delivered the news of my health diagnosis. If this were a stage play, the audience would understand that Connor and Lucy were the main characters, that the adult decisions or scientific breakthroughs would affect them most of all.

When I told them about the divorce, I said this: “There are many kinds of love. The most extraordinary kind is the love God has for us—it’s eternal. And then there’s the love parents have for their kids—bigger than you can possibly imagine. There’s friend love, which can be magical, but it can also change over time. And then there’s married love. This kind of love is extraordinary, because it requires so much, and also gives more than you can imagine.

“But for reasons we’ll never fully know, your dad’s love for me shifted from married love to friend love. And because of that, we can’t be married anymore. This is terrible. We’ve now been called to reimagine our family, and we’re going to find ways to be brave throughout.”

I communicated truths to them because I couldn’t stomach the notion of telling my kids falsehoods after having myself tasted the poison of betrayal. But as with medicine, I learned in those days the value of dosing. I would tell them the truth with a gentler dose, waiting for them to reckon with their dad’s decisions when they were older.

When it came time to deliver the news of my health diagnosis in July 2019, I told them the truth again, with a careful frame: “Okay. Here is the lousy news and why I’ve been so tired lately: I have colon cancer.” Deep breath. And then: “But do you see this bag of liquid hanging up here connected to my arm? This bag of clear liquid is a miracle. That said, it’s a hard miracle. I’m going to feel like crap while I take it, and it’s going to be a slog. But this is not poison, despite what you might hear some say. No. This liquid is going to save my life, and it’s dripping into my arm because for decades people have studied, worked hard, and studied again to make it as safe and effective as possible. There’s simply nothing poisonous about that.”

Decades of brilliant minds had expanded the possibilities of science to create this moment. Their work—their gift—emerged as a path. And although uncertain, the path came with a map we could follow. With divorce, if you’re fortunate, you may have experts to equip you with helpful tools and remarkable empathy. Still, there are no baseline data sets, no agreed-on measurement for emotional pain, few agreed-on maps to make the trip through the world of recovery and rebuilding.

During the early days of divorce, my family had stumbled through the uncharted territory. Like all divorces, our story belonged only to us, which created an inevitable season of internal reckoning and repair—a time that occasionally required a kind of brutal isolation. We were fortunate to have a community of family, new friends, and long-time soulmates who offered generous love through those days. But at its core, binding up the wounds of a family happens quietly in the interior life. If the campaign of those days was to emerge from the valley of despair to a new place—a place where our hearts would once again become dependably joyful and open—were we advancing at an appropriate pace? How would we know?

Divorce had no clinical trials to point the way to the most efficient or effective recovery trailhead. Divorce had no published reports that would help me know whether I ought to have insisted that Don—who had chosen to move hundreds of miles south—fly up for a parent-teacher conference. Divorce had no ninety-day scans to show whether the wounds of our hearts were healing without too much scar tissue.

While cancer threatened to take away my future—something none of us really own anyway—betrayal took away my past. My story, the one that I knew to be true for my marriage, no longer felt valid.

In the six years between my marriage ending and my health diagnosis, I rarely saw Don, who had moved to Southern California. While I worked out a creative schedule where the kids managed to see him frequently—he would be with them while I travelled for work, or they would fly to see him wearing their “unaccompanied minor” badges on the airline like frequent-flier champions—I didn’t have many opportunities to be in his company. There was little animosity. Just two lives—once intertwined, now on parallel paths—committed to the shared love of our children.

I found a workable, while unusual, rhythm to it all during those years, even as I managed the orthodontist appointments and Little League games on my own. If I held on to lingering bitterness, I didn’t express it, and I bargained that this part of my heart would diminish over time.

My health diagnosis crashed through our parallel paths and created a jagged, unfamiliar highway for my family to navigate. Don initially set up camp in Menlo Park as I began a series of chemo rounds, taking over primary parenting responsibilities. I walked around in a daze, still in shock over the turn of events, even while finding my footing at the novelty of seeing Don on a regular basis again. He had become more ghost than man to me in the previous years, and now I was sorting out how to small-talk with him as if we were right back at the beginning of early acquaintance.

As chemo rounds progressed, shock matured into hard work. The days were tough, but they didn’t decimate me. Don returned to Southern California, and the kids and I lived into our new normal.

Months before, I had learned that the chemo, hopefully, would take me to the most pivotal gate for any hope of survival: if the sizable tumour in my liver diminished, I’d be a candidate for surgery. And if surgery was successful, maybe I’d emerge as one of the fortunate ones—a patient who could live into a season where occasional chemo rounds might help keep the cancer at bay. Then I could once again imagine a future.

If you had to pick a worst day of the year for surgery, December 19 would rank high. Connor and Lucy were in the thick of finals, my brother’s and sister’s families had important Christmas obligations, and my extended network of girlfriends had holiday plans and trips booked months before.

I knew I would be well cared for in the hospital, but after comparing notes with a few others in my abdominal surgery club, I learned that the first days home would be painful, harrowing, and hampered by limited mobility.

I was passing for healthy while being gravely ill.

Once the surgery date was set, my sister, Mindy, and sister-in-law, Julie, volunteered to come and be with the kids through my hospital days, but they both needed to get home in time for Christmas Eve. If all went well, I would likely be discharged by Christmas Day, and I’d need a caregiver on hand for those first highly vulnerable days.

Here’s something people find surprising about lots of us with cancer: most days we look normal. Each cancer and treatment is different, but many of us move in and out of chemo rounds and scans and procedures more or less looking like ourselves much of the time.

I was passing for healthy while being gravely ill.

The duality had proved to be immensely helpful while navigating those early months with Connor and Lucy. I took lots of naps and went to bed early. We ordered more pizza than normal, and I remember once saying that the idea of unloading the dishwasher was just too much. But I still went to my office most days, took the kids to dentist appointments, attended school concerts, made breakfasts, carpooled, paid bills, listened to the latest gossip from their high school days.

The question I received more than any other in those days was, “So how are your kids holding up?” My reply was always the same: “Well, most days are bizarrely normal, and they seem okay. Are they googling the scary odds of stage IV colon cancer into the wee hours of the night? Maybe. But my theory here is that since I don’t look sick, it’s easier than you might think to not wake up every morning in a complete panic.”

The days after surgery would be different. I would look gaunt, sad, weak, shaky. My magic trick of living through an internal horror movie while twirling around as if I were in a romcom would come crashing down, and the kids would come to not just know but see the urgent reality: their mom was seriously ill.

So when I wrestled with the dilemma of who was best to be with me after my discharge, the answer became obvious: it had to be Don. The kids would need their dad in those days when I would be at my most visibly vulnerable. Plus, it was Christmas, and I was desperate to give them some semblance of continuity as uncertainty dogged our days.

This question of inviting Don back into my life to care for me at my most physically broken—into the full uncertainty, intimacy, and trust of our family—was distinctly different from asking him to get me home from the hospital after the diagnosis. That had been more of a baton pass, a decision to set aside grievances and awkwardness. But the upcoming post-surgery days, I knew, would require a different kind of courage. As a practical matter, my body’s brokenness would be ever-present. I would need a steady arm to walk the eight paces to my bathroom, and God only knew what might happen in the bathroom after I got there. I would need help getting dressed and even getting in and out of the shower. And the pain. I’d been warned there would be late nights when I would cry out for help, and knowing that the person I would be crying out to would be Don felt humiliating.

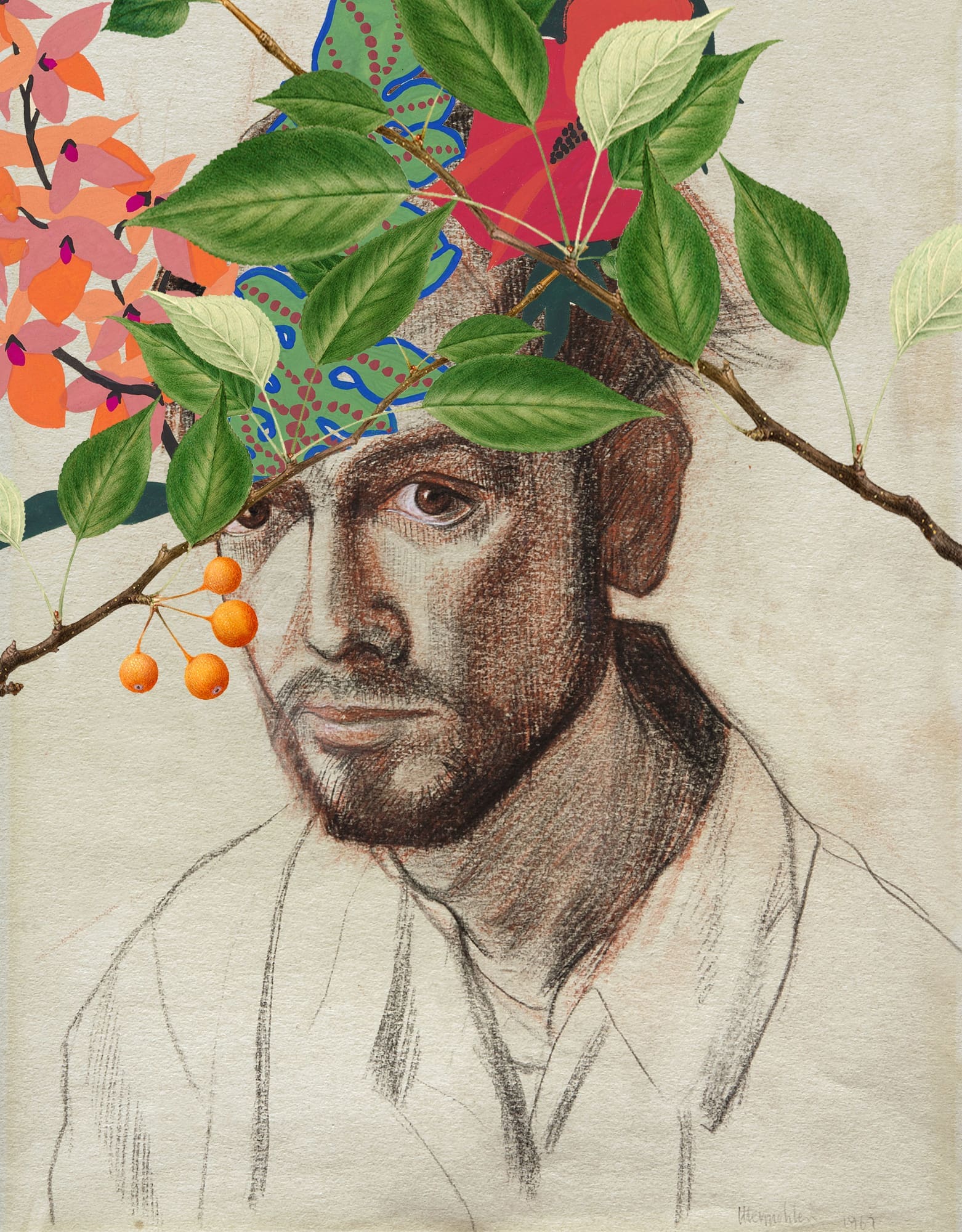

But ultimately all that mattered was Connor and Lucy. If they were going to hear their mom cry out in agony in the middle of the night, I wanted them to hear me call for their dad. After all those years of living on the other side of marriage, I wanted them to witness their parents doing for each other what they were always meant to do: tenderly walking alongside each other. If I was going to exit their stories far too soon, my highest parenting priority was to create a graceful bridge to their new normal. We’d cross this bridge, all three of us holding hands, even if it meant I would have to let go once we reached the other side. I would see them over to their new country and remind them of the gorgeous traits their dad held, and still holds. I would help them see that, like all people, their dad was a million different things—generous and impulsive, caring and sometimes self-serving, tenacious and often exhausted. For this chapter of their story, they would see a beautiful man who wanted to do everything he could to help me heal physically.

I asked Don to return.

And so he did. In the precarious days that followed the abdominal surgery, Connor and Lucy saw their dad—who had ended the family we had once all adored—sleep on the couch near the Christmas tree. They saw him gingerly walk up the stairs every hour or so to listen at the door to find out whether I was up in my bed whimpering. They saw him wash every dish, wrap every present, fold every piece of laundry, empty every trash can. They saw me receive Don’s gentleness and rely on him. They watched him create a safe harbour inside the most horrible storm.

And something strange began to happen. I came to understand that relegating Don to ghostlike status was a clever act of avoidance. I had given myself a permission slip to sidestep a true reckoning, a forgiveness that moves from intellectual abstraction to flesh-and-bone pragmatics. What’s more, given my physical vulnerability, I edged ever closer to forgiveness’s most essential paradox: that somehow in the forgiving, the person harmed no longer publicly (and even privately) retells the narrative of the wound. That is, both parties are made new. For the person who caused the harm, this is a beautiful release. For the person harmed, there sometimes can be a holding on to the story: Please know I’ve forgiven this person, but you should also know what they did to me. What I’ve learned through forgiveness is that the betrayal narrative has diminished. A new story has emerged, not always on my terms, but it is far more memorable, far more surprising.

How could I embrace the gritty nature of not just allowing but inviting Don to be my caregiver when I was at my most unguarded? Wouldn’t I lose myself, my standing, my leverage?

The stakes for me were never higher. Don knew every inch of me. When I arrived home from the hospital, he guided me up to my bedroom. He lifted my arms up and gently pulled my sweater over my head. And then my T-shirt. He glanced at the vertical incision that went from my diaphragm to my belly button. It was swollen, tender, red. He was careful not to let my shirt brush too closely to the scar.

I managed to sit up, and he unclasped my bra as I faced away. He carefully pulled my light-pink pajama top over my head. I managed to pull off my yoga pants while he sat on the floor ready for my feet to enter into my pajama bottoms. It was all a delicate set of careful manoeuvres, guided by Don’s perfect hands. His hands were the best hands I ever knew. Long, strong fingers. A palm that I could slide my hand into, like a key uniquely molded for a one-of-a-kind lock. At his best, he could stand in front of a room and use his hands to make a persuasive point, and all assembled would find their way into his palms as invited and captivated guests.

But for so very long I wasn’t a guest in those hands—those hands had intertwined with mine, and with my heart. Finding my way into his hands had meant finding a way into my favourite home of all.

Yet here I was. At home in my own bedroom, but no longer at home with Don. He had ended our hearts’ home. But there on that bed, ever so vulnerably, ever so slowly, forgiveness whispered its way in and enabled me to begin reimagining a new home for me, and for us.

Back when I was doing my best to move on from the end of my marriage, I understood that a key element to any hope of rebuilding hinged on our common discourse around forgiveness. I knew this language well; I had grown up the daughter of a pastor in a house where this virtue was the cornerstone for all norms. “Do I forgive Don?” I would say to a friend who wondered how I was doing a year after the divorce. “Yes, well, it’s a journey. But of course, that’s all part of the healing.”

I exuded this sleight of hand in my conversations, but it really was just obscuring the fact that my inner thoughts were swarming with obsession as I replayed and replayed and replayed the innocuous moments, painful memories, slights, glories, and devastations within our marriage. I cast myself as the victim of the drama and Don as the broken antagonist—more weak than malevolent. I found oxygen in this narrative: Don was a broken figure, and I was collateral damage. Sure, I’ve forgiven Don, I’d tell myself. I’ve forgiven him for his weakness.

It turns out that forgiveness is far more demanding, mysterious, and intentional—and somewhere in its work, an alchemy disrupter. Much to my shock, in the process of lying vulnerable before his care, I found myself gradually perceiving Don not as the person who had wronged me but as a beautiful child of God, his true, full self fully separate from what he had wrought. Somehow his past actions no longer clouded my vision of him; instead, all I saw was him.

It didn’t happen overnight, and it took some reckoning with my own fears. For years after the trauma of his betrayal, I assumed that truly forgiving him would erase me from the story. And then when I got sick, fast-tracking me to the cliff of death, the fears intensified. If I truly forgave Don, might he get away with emerging whole and free—maybe even a hero? “Look at how he cared for her when she was sick!” I could imagine people saying after I was gone. But where had he been when I was healthy? Would no one remember my true self, my unblemished value?

If forgiveness enables renewal—allows new dreams and plot lines to take hold—will the aggrieved be erased?

Deep forgiveness puts in motion both reckoning and renewal. What’s made new through forgiveness enables undiscovered stories to be formed. When I experienced this wave of forgiving Don to be a kind of washing experience at once cleansing my lens and restoring his humanity, the ways in which I was then able to relate enabled Don to begin his own reckoning for what had led to his decisions, an open gateway for a season of coming to terms. I felt no need to require penance, to correct, admonish, or litigate his process of reckoning. All I wanted to do was see and hold his true self.

This is forgiveness’s most crucial gift, yet it comes with a tension that’s complicated to work through in our polarized days. If forgiveness enables renewal—allows new dreams and plot lines to take hold—will the aggrieved be erased? Our arguments and even policy positions are often shaped by generational trauma, unfinished business that requires a constant cultural penance, a continuous return to the original harm, which no doubt come with a prequel of wounds that deserve a hearing. The aggrieved always deserve justice, and they deserve for their stories to be told and remembered in detail. But sometimes it seems we get stuck here, allowing our futures to be shaped only by how we litigate our yesterdays. If the aggrieved are given a chance to embrace a deeper forgiveness—in my case, slowly replacing marital trauma with a newfound harmony as my narrative’s focal point—I wonder whether more of us might instead see those who have caused pain the same way God does: viewing the action that caused harm as existing within a soul that holds an infinite amount of potential, including goodness.

If betrayal had taken away what I understood as my past, perhaps I could help set in motion a future that cancer threatened to shorten. As I embraced true forgiveness, I came to see that my receiving Don’s care might form new chapters for Lucy and Connor to develop alongside their dad. This bearing witness to his accompaniment could be a legacy gift, one that might change generations. Even so, this was a gift wrapped in whispers rather than bright ribbons. Quiet and deep acts of grace would gently nudge my children’s imaginations to create a restored family, where their own children might come to adore their Grandpa Don and his best traits.

I’ve learned this takes time. It may take a lot of time. There will be days of momentum followed by days when the crushing memories feel like an entrapment leading to paralysis. I grew to see this aim toward forgiveness more like how a sailboat tacks: a back-and-forth rhythm that, remarkably, results in progress toward the destination. Within this non-linear journey, if there’s a discipline to adopt, perhaps it’s a question that I have learned to hold close: What stories do I hope Connor and Lucy will one day tell? Will their stories equip them to dream with ambition? Or will they cling to narratives that stall their potential?

The future doesn’t belong to us, but we can shape it. Forgiveness is a direction, and ultimately a plot shift. A person who is fully forgiven might develop a heart with a deep well of gratitude, an uncommon space that maybe—just maybe—equips him to usher in a new medical breakthrough. A person who forgives trusts that a release doesn’t mean an erasure, even as she holds the mystery of who will tell her story.

Forgiveness creates liberation in the truth that whatever story you inhabit today, there will be more chapters to create and to live.

There will be possibilities. There will be grace.

After a valiant battle with colon cancer, Amy Low died on Wednesday, November 27, 2024, surrounded by her family. She wrote this essay for Comment in the final three months of her life as an ode of hope to all those wrestling with the complexity of forgiveness. We are grateful for her courage, and the grace with which she stewarded her suffering. Sections of this essay first appeared in her book, The Brave In-Between, published in June 2024 by Hachette.