F

For every action, Sir Isaac Newton told us, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Newton was talking about the material world, the world we inhabit. Humans are gloriously, infuriatingly material beings. And yet, despite attempts to persuade us otherwise, we are not merely material beings, devoid of agency or free will. We possess a stubborn capacity to reflect, evaluate, and decide what kind of reaction we pursue. Not all human reactions are equal or opposite.

Humans can choose to absorb an action, to learn from it, to respond nominally, orthogonally, or not at all. Alternatively, we might take a different course, upping the ante and reacting with an energy and violence absent from the original action. I can turn the other cheek, or I can slap both of yours. You can do the same. And then? Well, as Yeats wrote a century ago in “The Second Coming,” a poem endlessly quoted in our time, “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; / Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.”

The world, and certainly the news, feels somewhat anarchic now—unfamiliarity, unpredictability, anxiety all crowding the frame. What we are witnessing, however, is not (yet) mere anarchy but a(n over)reaction—or, better still, a course (over)correction.

We are all familiar with the idea of a course correction. You dream and drift when driving but suddenly find yourself jerking the car too far in your attempt to get back into lane. You overindulge at Christmas and endure Dry Veganuary to make bodily amends.

All living bodies course-correct; it’s how we thermoregulate and stay alive. Bodily metaphors—the body politic, social health, and so on—notwithstanding, however, human societies are not good at course-correcting, if only because they are made up of people who do not always agree on what, how far, or even whether society needs correction at all.

What I suspect, and fear, is happening at the moment is that, in the process of making a legitimate course correction, many Western countries, most obviously the United States, are embarking on a potentially harmful course overcorrection. Here is one example of what I mean.

Twenty years ago I wrote a book on asylum and immigration. Even then, people were very angry about both. “Stop This Asylum Madness Now” shouted the front page of The Sun on August 18, 2003, before warning the following day, “There is a timebomb ticking in our midst which must be defused.”

Taking my cue from theology rather than the tabloid press, I argued that we should be a bit more positive about asylum but a bit more negative about migration. The latter argument perplexed people and was sometimes greeted with incredulity. Did I not know how sensitive a subject this was? That how, even by talking about it, let alone being critical of immigration, I would give succour to racists and risk being labelled a racist myself? When I explained my argument to an academic who was later elevated to the House of Lords, they said, “Ah, so you’re offering us the Barking BNP argument, are you?” I never found out whether they were referring to Barking and Dagenham, the borough in East London where the racist British National Party were strong, or whether they meant barking mad. Either way the message was clear. The topic was best left alone.

It wasn’t. Over the years, it grew in volume and moved centre stage, but it was a slow process, not accompanied by any commensurate drop in immigration levels, which ceded political ground to agitators, disrupters, provocateurs. It helped bring Nigel Farage into Parliament, Reform to (near) the top of opinion polls, Front National to within spitting distance of the Élysée Palace, Alternative für Deutschland to the political mainstream, and Trump into the White House. None of these political actors is likely to have any moral qualms about using aggressively anti-immigrant (and anti-refugee) rhetoric, or to make much effort to distinguish between the two.

Good, people say. The “liberal elites” who supercharged immigration and then helped suppress legitimate debate on the topic had it coming to them. Perhaps so, but it won’t be the liberal elites who suffer from any course overcorrection here. However much lower-income people may have suffered from large-scale immigration—through wage deflation, housing shortages, or unavailability of public services—you can be sure that most asylum seekers and many immigrants will have suffered more. And yet, because of the political course we have taken for the past twenty years, sympathy for such people is at a low ebb.

The risk is that in a quite reasonable attempt to reduce the level of immigration, we find ourselves with leaders who legitimize a nastier, more aggressive, and dehumanizing approach to all immigrants and refugees. In our attempt to course-correct, we overcorrect.

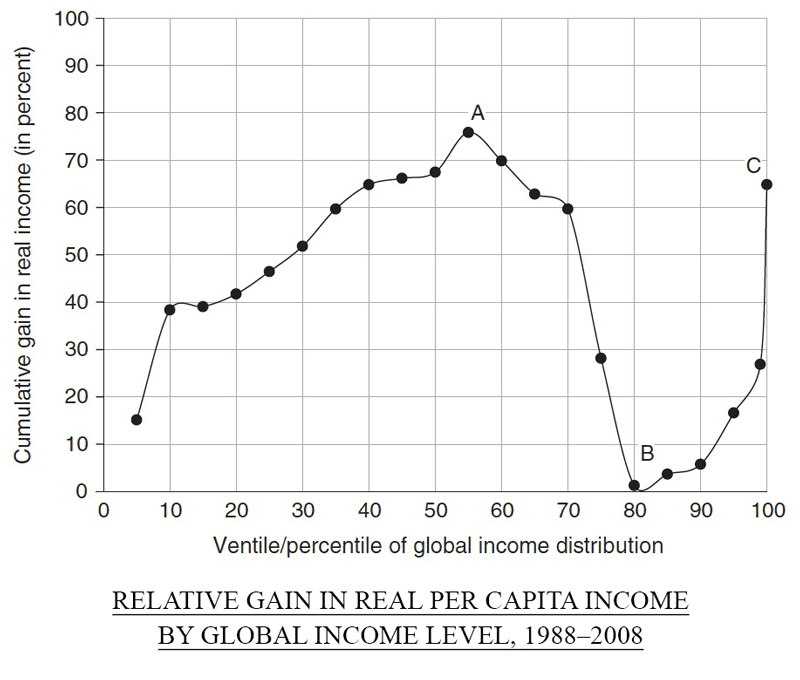

The more you look around, the more it seems like this is a recurrent pattern of our political moment. Take globalization. Over the past thirty years, trade barriers have come down, production has been offshored, capital has been invested overseas, supply chains have spread across the world, currencies have been united, and transportation costs have fallen. People have, overall, got better off.

But not all people. As the famous “elephant graph” demonstrates, over this period most income deciles across the world have got richer. People in developing countries have benefitted, as have the rich in developed ones. But there are exceptions. The poorest in low-income countries have seen their income grow only slowly, while the poor in developed countries have hardly seen any income growth at all.

The result has been politically momentous, with swathes of the once-working classes in America and Europe feeling viscerally “left behind” while everyone else, not least white-collar workers in their countries, has done so well. It was this economic tide that helped bring Trump into government in both 2016 and 2024, with his promises to reignite American industry, revivify the automobile industry, drill for oil, and “Make America Great Again.”

However little you think of Trump, the promise to work for a working class discarded by globalizations is a commendable one. That recognized, his chosen measure for achieving it is questionable and risks harming the very people it purports to save. The president may think the word “tariff” is beautiful, but the aggressive imposition of high-level tariffs risks a trade war that could increase import and business costs, generate higher consumer prices, reduce profits, deter investment, disrupt supply chains, destabilize markets, and trigger a recession.

Once again, it is early days. Everything depends on the breadth, depth, and extent of the tariffs and, of course, on other countries’ responses. Nevertheless, even for the wealthiest country in the world, this constitutes a risk. In the attempt to course-correct for the kind of globalization that thought blue-collar workers in developed nations would just swallow their humiliation, we risk overcorrecting into a trade war that leaves everyone poorer.

The overcorrection is not just economic. It’s political too. We in the West have never loved our political leaders. Mass Observation studies of Britain in the 1930s and 1940s reported the public describing the political class as “hypocritical” and “distrusted,” full of “twisters,” “clever rogues,” and “liars.” Skepticism toward political leaders is the price of democracy.

We in the West have never loved our political leaders. Skepticism toward political leaders is the price of democracy.

If, as many people think, healthy skepticism has long since tipped over into a corrosive cynicism, some kind of course correction is welcome. And yet we are seeing signs of a perilous overcorrection. Polls tells us that a perturbing number of (especially) young people say they want a strong leader, unencumbered by the tedious restraints of democracy, to “sort things out.” Donald Trump’s apparent preference for autocrats over the democratically elected leaders that have traditionally made up America’s allies adds fuel to this fire.

The trend has generated some excitable headlines. “More than half of Gen Z wants UK to become a dictatorship,” one headline claimed. Others have tried to dampen this ardour. “Our key conclusion . . . [is] that there is no deep issue with the principle of democracy among the UK public or younger generations,” reported King’s College London; “it’s perceptions of delivery that are the problem.” We must hope they are right, not least because this is one overcorrection that would not easily swing back. Come down too hard on immigration or free trade and you can negotiate and debate your way back. Come down too hard on representative democracy and there is no obvious political path home. Correcting for democracy’s undoubted inadequacies, we cannot afford to overcorrect our way to autocracy.

There is a similar risk with the law. Jonathan Sumption, a former British Supreme Court justice, has written at length about judicial overreach. His is not an indiscriminate attack on the British judiciary, which Sumption considers of a very high standard, nor on what is known as judicial activism, the way in which some judges are perceived to go beyond the proper limits placed on their roles by politics and legal precedent.

The problem is not so much judges going rogue as judges making use of the “living instruments” that permit them wide-ranging authority. In the United States, the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, passed at the end of the Civil War to prohibit the deprivation of “life, liberty, or property,” has been interpreted as potentially embracing any interference with personal autonomy and so used to justify all kinds of judgments, not least Roe v. Wade, which it could not possibly have had in mind.

In the United Kingdom, following the Human Rights Act (HRA) 1998, domestic courts found themselves with the right to strike down any rule of common law, regulation, or government decision that was found to be incompatible with the Convention on Human Rights. Even more frustratingly (at least for critics), Article 8 of the HRA—protecting private and family life and privacy of the home—has been invoked as widely as the Fourteenth Amendment and used to justify judgments on extradition, sentencing, abortion, same-sex unions, social-security rights, legal aid, planning, and noise abatement among others. The result has been a growing sense of political enervation and that the rule of law is degenerating into the “rule of lawyers.”

Some kind of course correction was, at least according to Sumption, needed. But what we are seeing is a potential massive overcorrection. Newspapers have whipped up hatred for the judiciary, most famously in the Daily Mail’s front page “Enemies of the People.” The Conservative government under Boris Johnson was known for playing fast and loose with the law, and the prime minister himself seemed to make a virtue of his contempt for rules. Trumpian America is worse. In early 2025 the American Bar Association issued a statement expressing grave concerns about “escalating governmental efforts to interfere with fair and impartial courts, the right to counsel and due process, and the freedoms of speech and association in our country.” It told of intimidation and attacks on the judiciary that one simply does not associate with America, at least not until now.

Once more, we should avoid exaggeration. For all the apocalyptic fears, Britain and America still enjoy a robust rule of law and have comparatively well-functioning, if underfunded, legal systems. But overcorrection looms. In the legitimate desire to address some of the more excessive legal powers secured by, for example, Article 8 or the Fourteenth Amendment, and to bring back into the political realm (of legitimate contestation) some of the issues that have recently been treated as legal (and therefore beyond debate), we risk breeding an indiscriminate contempt for the law and pitting justice against “the will of the people.”

Political, economic, legal . . . the risk is also (especially) social. Two quick examples.

Few subjects are as liable to divide people as DEI—diversity, equity, and inclusion—a lightning rod for disaffection. For some, it emblematizes the attempt to remake social values in the image of a particular urban, liberal conception of the good, in which all traditional and closed communities are naturally suspect. Whatever one thinks of this, Trump’s response is an overcorrection. His rhetoric—DEI is “dangerous, demeaning, and immoral”—risks legitimizing an outright rejection of the principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion, which, however much they have been weaponized, are often good things. In the attempt to course-correct for fallacious target-mongering and identitarian box-ticking, we overcorrect our way to open indifference or even contempt toward those who don’t fit the mold of “normal.”

Or take the connected subject of our attitude to men and masculinity, a word whose contemporary association with “toxic” is highly instructive. That men can be toxic is hardly in doubt. Nor, however, is the fact that “boys are struggling in education, more likely to take their own lives, less likely to get into stable work, and far more likely to be caught up in crime,” as the Centre for Social Justice recently reported. Unfortunately, the overcorrection here has come in a particularly ugly form, with boys who are “crying out for meaning, direction and role models” drawn to “role models” like Andrew Tate, who make no secret of their violence and misogyny.

Let me try your patience with one more example, close to my heart, before I draw the strands together. Theos, the Christian think tank for which I work, was, by some quirk of divine humour, launched a month or so after Richard Dawkins’s The God Delusion was published. For five or more years after that, the mood music was all about how Christianity was irrational, harmful, and a threat to public life, permissible just as long as it remained private.

Years later, such anti-religious hostility is seen as a bit embarrassing, and a surprising range of (very different) people are making a positive case for Christianity’s importance and relevance (if not always for its truth). I cheer. Well I would, wouldn’t I? But it is only two and a half cheers, because with the resurgence of faith in public life we are hearing a whole load of phrases—“Christian culture,” “Christian nation,” “Christian civilization,” “Judeo-Christian values”—that are vague at best and suspect at worse. More alarming still, some far-right and extremist groups in Europe and the United States have taken recourse in Christian rhetoric and symbols as a way of rejecting others, whether they be Muslims, migrants, or multiculturalists. In other words, in an attempt to correct for the narrow-minded and sometimes nasty attempts to exclude Christianity from public life, we risk overcorrecting our way to a kind of muscular, vaguely cultural Christianity that can be weaponized to exclude people we don’t like and that has very little to say or do with the suffering servant and saviour, Jesus Christ himself.

In an attempt to correct for the narrow-minded and sometimes nasty attempts to exclude Christianity from public life, we risk overcorrecting our way to a kind of muscular, vaguely cultural Christianity.

Two obvious questions spring from all this: Why has it happened now, and how should we respond? Neither affords an easy answer.

For those confident that the universe has a moral arc that bends toward justice, this is simply an expected, if not predicted, counter-warp. Justice always beckons. No one said it would be easy. We put our heads down and we persevere. For those of a more Hegelian bent, this is just how human history proceeds, one thesis overcorrecting into an antithesis before a new, more stable synthesis is reached. Either way, there is direction and destiny to human affairs, which even moments of overcorrection cannot erase.

Other, more sobering philosophies are available, however. Perhaps this is simply what happens when you find yourself in a modern Thucydides Trap, part of a once-dominant empire (“the West”) that is facing the prospect of its eclipse by a new rising power. Geopolitical anxiety and domestic anxiety feed off each other, generating ever more passionate intensity as the gyre widens ineluctably and things fall apart.

Alternatively, and arguably even more worryingly, perhaps the period of post–World War II stability and solidarity was just a historic anomaly, sustained by the collective memory of what the alternative had been (depression, unemployment, warfare, collapse) and by subsequent attempts to build an international infrastructure that tamed ethnic and nationalist energies. Perhaps we are simply returning to the volatile status quo ante in which the loyalties of land, blood, and God sweep all aside and the strong know it’s their right to decide the fate of the weak. I confess I vary in my view here, convictions about the nature of God and reality in a frustrating—no, let’s be positive, in a creative—tension with what I know of the human heart and see on the human news.

How we respond will be influenced by our philosophy of history, but—returning to where we started—not mechanically or automatically. Reactions need not be equal or opposite. We can respond orthogonally to a situation, with hope even when it seems hopeless. We can, if we choose to, respond graciously.

Luke’s recounting of the parable of the good Samaritan contains a twist that is often overlooked. Jesus tells the parable because the lawyer asks him who his neighbour is, but he follows his story with the question “Which of these three do you think was a neighbour to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?” It’s a pertinent inversion. The neighbour has gone from being the moral object to becoming the moral subject, from being the one about whom the lawyer was pondering his duties to being the one who does the caring in the story.

It is a salutary lesson for a time like this. When we dig down into our trenches, it is difficult, indeed threatening, to ask what “we” can learn from “them.” The parable nudges us away from an often legalistic and self-satisfying thought, “I will treat my ideological enemies with kindness,” to an altogether more challenging one, “What can they teach me? What can I learn from them?” Only by refusing the temptation to overcorrect, by replacing the powerful centrifugal forces pulling us apart with deliberate if uncomfortable centripetal ones, can we stop things from falling apart.