M

My wife Erika suffers from a nasty, lifelong shoulder condition called multi-directional joint instability. It means the muscles and ligaments around the glenohumeral joint are weak, creating a laxity in multiple planes. It means she can dislocate her shoulder doing simple, non-traumatic movements. She has dislocated one side or the other carrying a camping mattress, shaking out a tablecloth, passing snacks to the kids in the backseat, and sometimes for what looks like no reason at all. It’s worse on the right side but affects both shoulders. It’s chronic and genetic: her brother has it, her mother too.

When it slips out, it usually slips back in within a few seconds—shocking, scary, and painful, yes, but it’s over and done often before the rest of us even realize what’s just happened. But last fall I got a call saying it happened to her during a shift at work. Her co-worker said that Erika was lying on her back on the floor, her shoulder out of joint and not going back in, and that an ambulance couldn’t get there for hours. I drove over, helped her sit up, helped her get to her feet, and drove her to the emergency room at the city’s biggest hospital, Erika gasping and shrieking at every bump and pothole that jostled her injured shoulder.

The triage nurse gave her a Tylenol and said the wait time to see a doctor was thirty hours. We got her registered anyway and then sat in the waiting room, trying to decide whether to stay and wait or drive to another hospital. I called a friend, who biked over with a tablet of Lorazepam, hoping it might help her relax enough for the shoulder to reset itself. It did calm her down, at least a little bit. But her shoulder was still all wrong. The doctors got her into a room in two hours because, they told her, they would never, ever leave a shoulder dislocated for thirty hours. Even after they sedated her, it took three doctors twenty minutes of pushing, pulling, and wrenching to get the joint back in place. For the next three months she alternated between holding her arm bent and close to her chest and resting it in a sling.

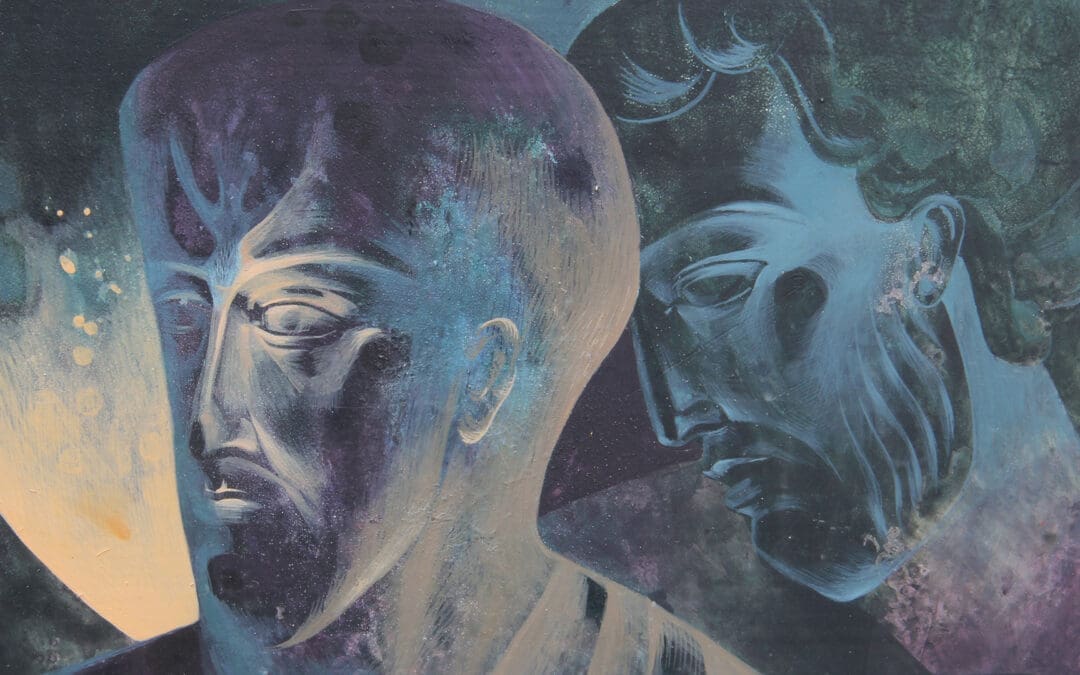

In the North Carolina Museum of Art there’s a 2,200-year-old marble statue of Aphrodite. Her face is worn and her nose is all but gone, but the carved curls in her hair are still vivid and clear. The description plate says that she’s standing next to a dolphin, but to me it looks like a Christmas ham poking out of a shopping bag.

She is beautiful indeed. But far more than her obvious beauty, what astonishes me is simply the enduring presence of this ancient object made by human hands twenty-two centuries ago. Like most of us, I suppose, I have been swept along in a stuttering, frenetic presentism, the frantic feeling of everything moving so fast it makes even the world of twenty years ago seem distant and quaint—before smartphones, social media, and whatever political time this is now. By contrast, there is this statue, 110 times older than Facebook, beautiful, commanding, recognizable. Thirteen hundred pounds of cool, mute Greek marble. Both of Aphrodite’s arms are missing, broken off just below the shoulders.

Before she became the rector at our church, Bonnie spent a decade being mentored by the leaders. She went to seminary, finished her MDiv, was ordained as a deacon, and then was assigned as a vicar. And then she got cancer. She took the better part of a year away from work, undergoing the usual oncology rigours, surgical, chemical, and radioactive. Her first Sunday back in the pulpit was Easter Sunday, and she opened her resurrection sermon with “I do not want to die.” I don’t remember the rest of it, but I do remember crying through most of it. I told her later I thought maybe she had preached the incumbent’s retirement sermon.

I do not want to die either, at least not these days. From time to time my mental health can take such a precipitous nosedive that I do in fact want to die, a harrowing and bleak longing simply not to be that can sometimes drag on for months. For no observable reason, my thinking slowly bends to a closed and chaotic, hopeless loop, and the only whiff of relief I can conceive of is death. I have made vows to God and to my children not to kill myself. But there are times—prolonged times, insufferable and despairing times—when I regret ever having promised anyone anything of the sort.

As I’m aging, my mental health is stabilizing, the black dogs less prone to circling. Medication, talk therapy, spiritual disciplines, spiritual direction, and very good friends all help to ground me and keep my head on straight. So I do not want to die. But even more, or maybe just in a very different way, I do not want my wife to die. I’ve known her thirty-two years—eleven and a half thousand days, give or take. I have loved her since I was seventeen, the same age my son is now. By this point, every day, every plan, every decision, every hope is woven with her presence. And she will die, of course. So will I. Duh. And just like when my daughter was born and I knew that something spectacularly transformative had taken place and almost nobody in the world cared or even noticed, death, when it comes for my wife or me, will be seismic and earth-shattering, and almost nobody in the world will care or notice. Aphrodite with the broken arms makes me think about my wife, her particular fragility and vulnerability, her mortality and mine. It’s pretty on the nose, I know, but there it is: ancient statue of the goddess of love with the broken arms; and my beloved with the lax muscles and ligaments of the glenohumeral joint. Love and mortality and all the rest. I do not want her to die.

Aphrodite with the broken arms makes me think about my wife, her particular fragility and vulnerability, her mortality and mine.

Even though I am a committed, unequivocating, and to the best of my abilities faithful Christian believer, I do not feel much consolation in the often-recited but hard-to-believe promise of the resurrection of the dead. There was a time I felt flummoxed by the basic atomic mechanics of our promised resurrection—that is, how to put back together bodies from shared constitutive elements. If I am literally composed of some of the very same atoms as my ancient ancestors, how will the resurrection sort out the bits? Whose incorruptible body gets what carbon, oxygen, magnesium, and potassium? Ah, but the quaint questions about resurrection have grown much, much harder. These days the whole thing feels pretty fantastical.

Shoulder Sublux Pantoum

Her sling has useful but confusing straps.

Over one shoulder, behind the other,

Around the back and the side,

Devised to hold her arm close and safe.

Over one shoulder, behind the other,

I help her wrap the wounded shoulder

All to hold her arm close and safe

And not entirely but mostly useless.

I help her bind her wounded shoulder,

And she is stuck with waiting,

Right arm not entirely but mostly useless,

The busy woman is stalled, stuck.

She is stuck in the waiting

For the surgeon to call with a follow-up.

The busy arm is stuffed and stuck.

My load is heavy and growing more so.

When the surgeon calls with a follow-up,

One waiting ends, a healing wound begins,

Life’s heavy load growing more so.

But now we wait. We wait.

Waiting will end, but the wound opens.

She with the weak shoulder took my strong name.

And so we wait, we wait, and home

Feels strong and hard, firm and moving.

She with the weak shoulder is Armstrong.

We decided this. We chose one another.

Our life is hard, but strong, firm and moving.

Her sling has useful but confusing straps.

While we were in the waiting room last fall, my wife, flushed and frantic, looked around the room and said, “It is remarkable how fragile our bodies are.” In front and behind, to our right and our left, were two dozen others in various states of suffering and distress, men and women all vulnerable, fragile, and in much need: the silver-haired man closest to us in so much pain he moved like a sloth; the young woman in a wheelchair with no pants, a thin jacket draped over her knees; the bearded man curled over and around three plastic chairs, head back and snoring contentedly, ass out and farting prolifically. Needy and suffering, all right, and each and every one of them a bearer of the image of almighty God. But it is hard for me to see much resemblance to the divine in the emergency room.

Nearly all my life I’ve done physically demanding work, the sorts of jobs that depend on strong muscles and healthy joints. Construction, bricklayer’s assistant, glazier’s assistant, tree planting, feed mill production. I love art, books, and ideas, but I pay for groceries and the mortgage mostly with my muscles and bones. I am grateful for these strong-enough arms, capable hands, and stable shoulders. When our three kids were babies, I loved nothing more than to hold each of them until they fell asleep in my arms; and when they were toddlers, countless times I tossed them as high as I could up into the air, a move that never failed to make them squeal with delight and ask me to do it again and again and again. These days I use my arms to lift and carry things for building basements, fences, and bookshelves. Last fall I had to kneel on the floor next to Erika and hold her in my arms and pick her up when she didn’t think she could go from supine to sitting, never mind standing and walking. And I offered her my arm on our walks throughout the icy winter months. I don’t lift weights at the gym, and I’ve always been self-conscious that my biceps aren’t as big as I would like them to be. They are, I must admit, more John Turturro than Brad Pitt.

Ah, vanity.

They may not look like much, but my arms are strong enough.

Part of the problem with my theology is so many years spent in classrooms with textbooks. So much of what I’ve learned about God has come from abstract, bookish, wordy learning—Sunday school, sermons, Bible college, seminary, endless books. I really am grateful for the lot of it, even the stuff I no longer really believe, as well as the stuff that I still wrestle with, which is nearly all of what remains. But all of that thinking about God has biased my understanding toward tidy, orderly, rational theology. Socrates figured that the unexamined life was not worth living. Fine. But the overly examined life is not truly lived. I’m at the age where, if I’m not careful, all these ideas might make my heart ossify, all my feelings turning from tenderness into crankiness and complaining, the realities of existence not aligning with all the reading and thinking I’ve spent so many years doing.

Socrates figured that the unexamined life was not worth living. Fine. But the overly examined life is not truly lived.

I don’t know how to reconcile the crass earthiness of the suffering bodies in the waiting room with my overly pious and bookish sense of the holiness of God. Something has to give. The holiness needs to be lowered, the suffering raised. “My strength is made perfect in weakness.” Paradox or contradiction? I wish I could call it a contradiction, opt for the tidy clarity of either/or and get on with things. But life keeps confounding the categories of my best, clearest, rational ideas. That sleeping, flatulent man in the waiting room: image of God. The half-clothed woman: image of God. Sloth-man: image of God. My wife, whose out-of-place shoulder muscles kept spasming with such violence it flung her back in her seat, her distended tissues sending signals to unthinking nerves that keep trying to somehow right the anatomical wrong: image of God.

Marble is a metamorphic rock made from transformed limestone subjected to pressure and heat over tens of millions of years, and limestone is a sedimentary rock that starts as the skeletons and exoskeletons of sea creatures deposited over millions or tens of millions of years. Ancient Greeks quarried marble from many sites across the region. The snow-white marble of Aphrodite with the broken arms may have come from Naxos, meaning it is stone that’s about 200 million years old, give or take five or ten million. The carved image of the goddess, two millennia old, is beautiful, broken, and worn. And my wife, fragile and mortal image bearer of almighty God, turned fifty last year. Given her family lineage, she could well see another forty years, God willing. She, too, is broken and worn.

First-century Christian doctrine very quickly inherited and adopted as its own the ancient Hebrew myth that God stamped something of himself on these fragile, mortal bodies. I can understand why the ancient Greeks would have looked to something more durable than flesh and bone for images of their gods. But the Christian story that I am part of says no to the metaphysics of stone gods. When Elijah was bereft, God showed up not in the tornado, the earthquake, or the firestorm. If God picks fragile flesh to bear his image among myriad creatures, and then becomes exactly that kind of flesh himself, there has got to be something holy in suffering, the presence of the sacred even in the waiting room. That weird doctrine of resurrection and precisely what happens after flesh and bone turn to dust, whose molecules and atoms wind up where: God’s problem, not mine. Every year at the start of Lent I get the ashy cross smeared on my forehead: “Remember, son of Adam: from dust you have come, and to dust you shall return.” Never mind what happens after all this; my origins are every bit as weird and mysterious. Beyond the basic mechanics of genetics and reproduction, I cannot say with any real confidence or authority how I got here, or who I really am, ultimately, what my consciousness is or what it means.

It feels like an uncrossable chasm between what I think of as capital-“G” God and these fragile bodies, but the problem is probably me. I have my bookish God held up too high, mortal flesh held down too low. The Greek goddess, marble, mute, worn down. Every Sunday, Bonnie preaches some iteration of the same basic message: that the Son of God made himself far more fragile than even this broken statue. My wife is stamped with imago Dei, like the image of the monarch pressed into the coin. And then the crucified and risen Christ has tender, pink scars from the flogging, the nails, and a final spear through the abdomen, callouses on his fingers and palms from the carpentry work, thick skin on the soles of his feet.

During a prolonged deep freeze in February, Erika had a day surgery to repair a torn ligament, tighten some muscles and ligaments, and wind a muscle around to cover a groove in the bone that kept causing the dislocation. Recovery so far has been difficult, painful, and frustratingly slow. Three weeks after surgery, she was still waking up five or six times a night with muscle cramps and back spasms. I would get up, turn on the lamp, adjust her elaborate, teetering stack of pillows, help her out of bed. I would help loosen the straps of her sling and heat up some warming pads to hold on to her shoulder as she tried to stretch her arm to loosen the atrophied tissues in her upper arm. Sometimes she would wake up angry and afraid. She wanted my help but wanted me to leave her alone; she needed me to adjust the sling but flinched and gasped at even the gentlest touch. In tears she would tell me, “I can’t do this,” and I would try to be gentle and tell her, “Yes, you can.” The cumulative exhaustion of interrupted sleep reminded me of caring for a newborn. But this is my beloved, my one-and-only, my wife, my partner.

We are in a period of real inequality, she and I. I have to help her with the most basic quotidian activities: getting up, taking a shower, getting dressed, putting together something to eat. For a full month, I had only two days of paid work. I was full-time caregiver to Erika, plus doing all the cooking, cleaning, laundry, grocery shopping, filling the car with gas, shuttling the two kids still at home to their various events. I’ve asked those kids to help with a few of the household duties, and they’re mostly willing and fairly capable. But I’m still doing most of it on my own. Erika can do so little for herself, almost nothing for the rest of the family.

I think of the husbands and wives I’ve heard complain that their partners have changed: that he isn’t the one I married, she isn’t who she used to be. None of us are, of course. On the dresser there’s a photo of Erika and me on our wedding day, half a lifetime ago. We are both younger, firmer, less wrinkled, with less grey hair. We look hungry for each other, eager and naive. We have no idea what’s coming, not a clue. Nobody does. This has all been far more difficult than either of us could possibly have imagined. Not just the shoulder troubles: everything. Hopes and dreams that have evolved or faded, sexual hunger that has waxed and waned, unresolved arguments, the great toll of parenthood, perennial frustration, hurts, and disappointments. She’s changed. I’ve changed. Neither she nor I is made of stone. The marble statue lasts for millennia, and when it breaks, it will not heal. Erika and I last a few decades. We grow and get strong, weaken and break, heal and change. Fragile flesh. And then we die. Everyone owes the earth a corpse. Dust to dust, back to constituent molecules and atoms.

Frederick Buechner said, “Either life is holy with meaning, or life doesn’t mean a damn thing.” I’m all in on the first half, so all this fragile stuff must be the location of holiness, including—especially—our fragile, breakable, wounded, damaged flesh. God’s love is not fixed and chiselled stone. The love of God is fragile and broken; the love of God is gruesome. It must be. The divine has made its home within the common and base, the hurting and hairy, the moaning and afraid, the half-covered and desperate, the snoring and flatulent. The sacred smack dab amid the profane. “The reason I speak to them in parables is that ‘seeing they do not perceive, and hearing they do not listen, nor do they understand.’”

Maybe one day I will understand and learn to look low enough to find God. I have a bias for the stable and firm, something I can lean on, and trust, the stone of a statue that endures centuries. I’m not holy enough to see past the pain and fear in Erika’s eyes. I’ve seen that look before when she’s dislocated her shoulder, but it usually just pops back into place. I’ve seen that look, too, three times over, when each of our children was born. It is wild, animal, irrational, ferocious. She is the most steady, calm, measured person in our family, but now she is laid low. Image of God, Image of God. Capital-“I” Image, capital-“G” God. The Almighty: wild, tender, feral, animal; willing and ready to be wounded. The God whose love is gruesome.