O

On the night of September 7, 1964, in a brief but unforgettable moment, American TV viewers saw a commercial that would forever change the landscape of political advertising. Titled Peace, Little Girl, but later popularly known as the Daisy Girl ad, it begins with a little girl in a peaceful meadow filled with the sound of chirping birds. As she counts the petals she plucks off a daisy, her tender voice wavers and stumbles over the numbers. Suddenly her count is replaced by an ominous mission-control countdown. She looks up as though acknowledging the interruption. Her image freezes, and as the camera zooms into the pupil of her eye, the countdown reaches zero and a nuclear bomb explodes. As its fire swallows the world, we hear a voice-over: “These are the stakes! To make a world where all of God’s children can live, or to go into the dark. We must either love each other, or we must die.”

The voice was Lyndon B. Johnson’s, and the one-minute TV spot was part of his 1964 presidential campaign against Barry Goldwater. Although the ad aired only once, its controversy ensured widespread media replays and analysis, which ultimately helped sear it into the national psyche. By the time I was born, the commercial had become a cultural touchstone and a symbol of Cold War anxiety. At some point I saw it myself. Where or when I don’t know, but it struck a deep chord, earning a place in the visual archive of my mind alongside The Day After and Threads, movies made in the early 1980s that I saw as a young boy on TV. The ad joined the grim canon of images that early on instilled in me a raw, unshakable dread of nuclear disaster that has never loosened its grip.

It is said Daisy Girl marks the birth of attack ads—that it unleashed a new genre of fear-based political campaigning. Its influence is certainly still felt in the commercials and print ads that bombard us every election cycle. But while it was groundbreaking, a closer look reveals its debt to a rich tradition of biblical representation.

Coming off the recent charged election season, the ad bubbled up as a faint memory, so I looked it up on YouTube. When I watched it again, its vintage cinematic quality made me think of it in a larger art-historical framework. I was intrigued by Johnson’s invocation of religion in his fire-and-brimstone voice-over, which, coupled with the nuclear detonation, transformed the ad into a depiction of divine wrath. Ironically, it aired during a telecast of David and Bathsheba on the NBC Monday Movie—another scriptural reference to frame it! I realized that in addition to looking forward to the tactics of manipulation used today, the commercial also looks back to historical representations of the end times. In doing so, it still evokes fear, but within a context of collective moral responsibility. This places its underlying message in sharp contrast to that of contemporary ads whose aim is often simply to weaponize fear to foment anger and create division.

Indeed, we’ve grown accustomed to political messaging that invokes existential threats: ads today feature societal decline, economic instability, cultural division, threats to security and personal freedoms, and the erosion of democracy. But in its references to the visual and thematic conventions of apocalyptic art, Daisy Girl imbues a political decision with eschatological meaning, placing the viewer in the role of moral witness to a cosmic drama of salvation and destruction. Also, and this is key, unlike today’s demographically targeted ads, its warning is addressed to everyone, regardless of political view.

Daisy Girl aired amid Cold War tensions, just two years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, a time when fears of global annihilation loomed large. The tensions of the era were reflected in films like Dr. Strangelove, Seven Days in May, and Fail Safe—all from the same year the ad appeared—while the civil rights movement, women’s liberation, and student movements, along with counterculture protests, added to the unrest. Johnson’s Democratic campaign directed this climate of fear toward the nation’s sense of moral urgency, making the spectre of nuclear war feel like an immediate and personal reckoning for the American public. To this end, the campaign cited Goldwater’s positions and statements supporting aggressive military policy, his vote against the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, and his talk of using atomic weapons in the Vietnam War, thus casting him as a reckless warmonger.

Despite its stark simplicity, Daisy Girl packs a cinematic punch. Watching it again, I was reminded of Bruce Conner’s experimental films from that period, which, coincidentally enough, led in 1976 to Crossroads, an unforgettable short film that used footage of the underwater nuclear test Operation Crossroads. In the original archive footage Conner appropriated, the bomb’s mushroom cloud had been shot from different angles. The artist played the terrifying images back in slow motion, creatively pairing them with a minimalist soundtrack by Patrick Gleeson and Terry Riley. Daisy Girl’s editing, with its striking cuts and unsettling rhythm, brings to mind the rapid montage, found imagery, and stark juxtapositions found throughout Conner’s films, all of which challenged cinematic norms. Appropriately, the ad was created by the agency Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB), whose principal founder, Bill Bernbach, viewed advertising as more art than science.

My love of cinema has always been closely tied to my study of art, and it was my recognition of the ad’s resemblance to avant-garde films of the period that led me to cast my net across art history more generally. I began to search for visual precedents—works that employed jarring contrasts and symbolism in similarly unexpected ways. I had already identified the ad’s biblical undertones, but it was only through this exploration that I grasped how deeply its imagery was embedded in the long tradition of apocalyptic art.

The Art of Apocalypse

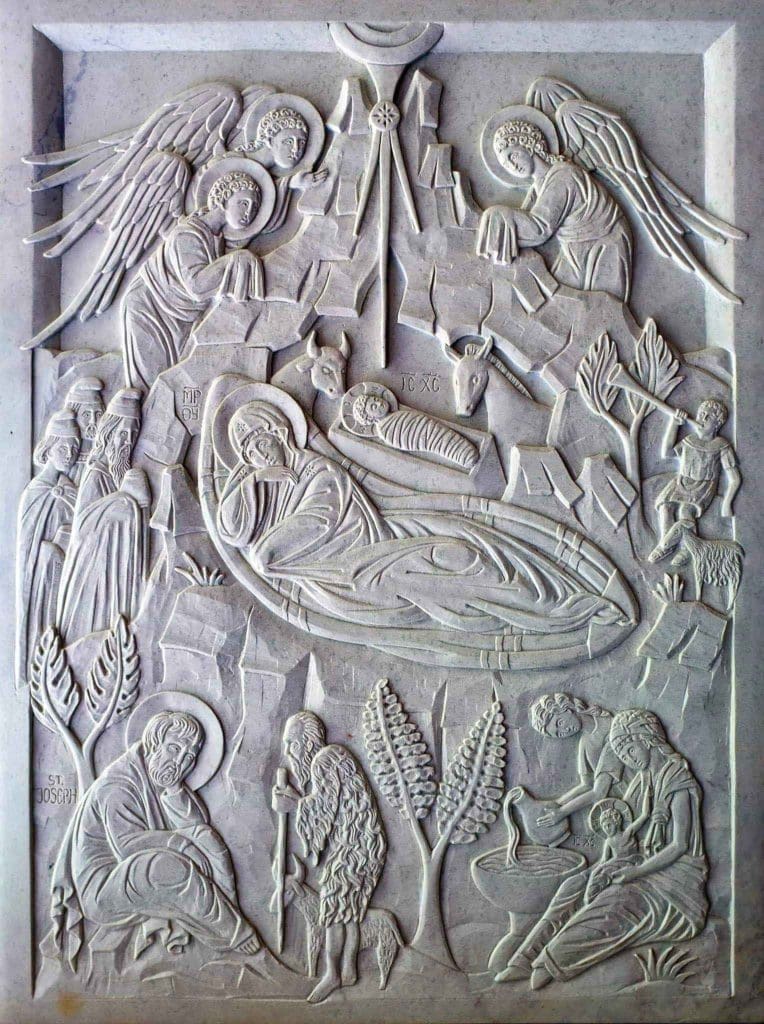

For centuries, art inspired by the book of Revelation has helped societies make sense of crisis, turning catastrophe into something legible. From the fourth-century apse of Santa Pudenziana in Rome to the vast Last Judgment frescoes that loomed over medieval churchgoers, these images made divine justice feel immediate, inescapable. By the twelfth century, depictions of judgment had moved beyond cryptic symbols to sweeping, narrative-driven compositions, carved over church portals or stretched across towering interior walls. In illuminated manuscripts like the Trier Apocalypse and the Lambeth Apocalypse, angels, beasts, and cosmic upheaval play out in richly detailed scenes, reinforcing Revelation’s warnings for a largely illiterate audience. Artists like Michelangelo later monumentalized the Last Judgment, making it something that framed religious experience itself. But Revelation’s imagery was never static—it was sharpened into religious propaganda for the Reformation by Lucas Cranach the Elder, reimagined as mystic vision by William Blake, and transformed into stark, unearthly terror in Albrecht Dürer’s Apocalypse woodcuts.

Even as the Enlightenment pushed aside divine reckoning in favour of human reason, the apocalyptic impulse never faded—it simply migrated.

The child in Daisy Girl aligns closely with the Lamb of God in Revelation—the fragile yet pivotal figure, both victim and object of hope, whose presence heralds judgment. In Revelation 5:6, the Lamb is described as “standing as though it had been slain,” embodying vulnerability and serving as catalyst for the world’s final reckoning. Like the Lamb, the girl in the ad embodies paradoxical characteristics. She exists in a moment of pure, unknowing innocence, plucking petals in a sunlit field, unaware that she has been cast in a cosmic drama. Yet she is the figure around which destruction gathers—her presence forcing the viewer to recognize what is truly at stake.

Daisy Girl’s jarring visual and auditory contrasts—the softness of a child’s voice against the harsh military countdown, the bright meadow against the cataclysmic explosion—mirror the moral binaries in paintings of the Last Judgment by artists including Giotto and Hans Memling, where salvation and damnation are divided with disturbing clarity. The ad’s countdown operates as a kind of secular doomsday clock, echoing Dürer’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and Blake’s Great Red Dragon, images suspended in the tension of catastrophe not yet realized. The images of the bomb blast recall The Great Day of His Wrath and The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, paintings made in the nineteenth century by John Martin that directly reference biblical subject matter. But we could also include War, a large triptych by the German expressionist Otto Dix that presents nightmarish landscapes reminiscent of a world scarred by nuclear devastation. The artist includes himself in the work, pulling a wounded or dead figure up from the battlefield. Dix paints himself in the guise of a religious figure, perhaps a saint, and the composition of War mimics a traditional altar. In this way the work also calls to mind Matthias Grünewald’s famous Isenheim Altarpiece, which, in its grotesque yet poignant emphasis on Christ’s suffering, could also be seen as a precedent for Daisy Girl’s expression of tragedy in the form of raw, unsettling imagery.

Like the apocalyptic art of the past—whether overtly religious or simply influenced by Christianity’s enduring visual language—Daisy Girl forces the viewer into an ethical dilemma by demanding a choice between peace and destruction. Similar to paintings of the Last Judgment, it compels an active, moral engagement so that viewers might confront their own fate and the consequences of human actions.

Apocalyptic art is often directly responsive to its time and place. It warns against specific sins or societal corruption while reflecting the fears of its era. A famous example is the Apocalypse Tapestry. Created at the end of the fourteenth century, the massive work, comprising ninety scenes, visualizes Revelation as a direct warning to France during the Hundred Years’ War. It spoke to ongoing military conflicts, the horrors of the Black Death, the instability of the French monarchy, and fears of societal collapse.

Even as the Enlightenment pushed aside divine reckoning in favour of human reason, the apocalyptic impulse never faded—it simply migrated. By the twentieth century, it had shifted into war propaganda, political satire, and modernist expressions of existential dread. Today, as the world once again finds itself haunted by war, pandemics, and climate catastrophe, Revelation’s imagery remains as potent as ever. It’s in the fictional return of the Four Horsemen galloping through the TV series Good Omens. It burns in the very real inferno of Los Angeles’s recent wildfires. It looms in the fear of AI-driven extinction, and in the ever-present spectre of global unrest. Clearly, humanity has never stopped envisioning the end.

Daisy Girl stands as a pivotal moment in this displacement of apocalyptic imagery from religious and artistic traditions into the realm of popular culture. It creatively distills that dramatic expression of moral urgency into a modern, secular context shaped by mass media and politics. And like the great art of this tradition, it speaks with the weight of collective responsibility in an aesthetic language that lands like a punch to the gut.

The Loss of Shared Symbols

Today’s political ads no longer seek to unite audiences through shared symbols or universal narratives. Instead, they fracture the electorate, using nano-targeting to precisely deliver different messages to separate groups, ensuring that voters see only what is most likely to provoke them and bond them to a tribe. As a result, the issues most likely to affect our collective well-being—like nuclear weapons, climate change, and economic disparity—are often ignored or given little attention because they don’t fit campaign strategies. This shift is the product of decades of evolution in political advertising that were marked by an increasing focus on emotional manipulation over substantive debate. While this is in part Daisy Girl’s legacy, that commercial still had one foot in an era when campaigns appealed to a shared national consciousness. The messages of today’s national campaigns—and the state and local campaigns they influence—cater to echo chambers.

Efforts to promote division for the sake of partisanship are far from new; the history of attack ads reveals a long tradition of using fear and opposition as tools of persuasion. Although Daisy Girl was unique in the way it tapped into what viewers already knew to elicit an emotional reaction, it was far from being the first negative ad. During the fledgling years of the United States, supporters of both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson smeared the opposing candidate during the presidential election of 1800. When the first attack ads appeared on screen in 1934, they took the form of fake newsreels staged by Hollywood producers to sink Upton Sinclair’s bid for governor. The key theme of an animated attack ad against Dwight D. Eisenhower by Democrat Adlai Stevenson’s presidential campaign in 1952 was Republican doublespeak. In the ad, a ringmaster introduces a two-headed character named Mr. Mac GOP on a circus stage beneath a banner reading “Republican Side Show.” As audience members ask questions, the two heads give contradictory answers. The ad used humour to portray the GOP as inconsistent and duplicitous in its messaging.

When a citizenry unites around shared concerns and recognizes their collective oppression, they create the strongest foundation for meaningful political action.

This idea, that the opposition is untrustworthy and will not follow through on its promises, has remained constant in political campaigns ever since. In more recent decades, fear-driven ads have only grown more sophisticated. The “Willie Horton” ad (1988) turned crime into a racial weapon. “Swift Boat Veterans for Truth” (2004) cast doubt on John Kerry’s military service. More recent campaigns have seized on fears of illegal immigration, crime, and economic collapse, not just attacking candidates but fuelling distrust and division within the electorate.

Yet, despite the long history of attack ads leveraging fear to shape public perception, the most existential threat of all, nuclear war, has largely disappeared from recent campaign discourse. Perhaps because it doesn’t fit neatly into the culture-war narratives that drive voter engagement. Or because both major parties are complicit in maintaining the status quo.

The absence of concern over nuclear fears in modern attack ads reflects a broader loss of shared cultural frameworks for processing overwhelming threats. Religious and artistic traditions once provided a shared symbolic language through which a society could confront fundamental moral and existential questions together. These offered widely understood imagery of suffering, judgment, and redemption. Their visual and narrative frameworks influenced how people processed fear, fate, and ethical responsibility, grounding societal anxieties in a collective cultural vocabulary. In a time of heightened political polarization, Daisy Girl’s message of shared vulnerability offers a counter-narrative, emphasizing our interdependence and the need for common ground.

Seeing the Crisis Together

The history of Christian art teaches that images can be used not only to manipulate but also to awaken. They can aid us in navigating our visual culture and help us distinguish between messages designed to incite panic and those that press us toward deeper moral reckoning and toward action that seeks not destruction but renewal.

While modern political messaging has largely abandoned the symbolic language once used to confront our greatest threats, Daisy Girl stands as a rare exception; and if we are willing to look, it still resonates today. By evoking the apocalyptic tradition, it did more than warn against a political opponent; it forced viewers to confront the fragility of life itself. And just as apocalyptic art has always compelled society to confront its shared fate, Daisy Girl pierces through the noise of political rhetoric—both then and now—revealing the urgent need for collective action.

Even in a secular age, the symbolic weight of the apocalyptic artistic tradition remains embedded in our collective consciousness, ready to surface in moments of true crisis. And while Daisy Girl is remembered for its political ruthlessness, its significance in modern visual culture lies in the fact that it speaks to that which threatens all of humanity, not just one or another political faction. Unlike today’s campaigns, which so often use culture wars as a smokescreen, obscuring the mechanisms through which real power operates, Daisy Girl appeals to something deeper: our interdependence, the recognition that our fate is bound together rather than divided by ideology. When a citizenry unites around shared concerns and recognizes their collective oppression, they create the strongest foundation for meaningful political action. This shared awareness transforms individual grievances into a powerful force for change, making it harder for those in power to divide and conquer their opposition.

At its core, this awareness of interdependence echoes a truth as old as Christian teaching itself—that we are all part of the body of Christ, inextricably linked, responsible for one another. Whether the danger is nuclear devastation, environmental collapse, or authoritarianism, it is this understanding of our shared existence that offers the only real guarantee of survival.