S

Several months ago I attended a lecture at Yale’s School of Medicine by the director of the most prominent bioethics centre in the world. Speaking about the future of bioethics, she listed some of the emerging topics in the field. When she mentioned “bioethics and religion,” she paused and vocalized the audience’s incredulity: “Yes, I know what you’re thinking: What could religion ever have to do with bioethics? It turns out, quite a bit!” As she chuckled at her own surprise at this revelation, another senior Yale ethics professor and friend of mine, seated next to me, whispered under her breath, “How quickly they forget.”

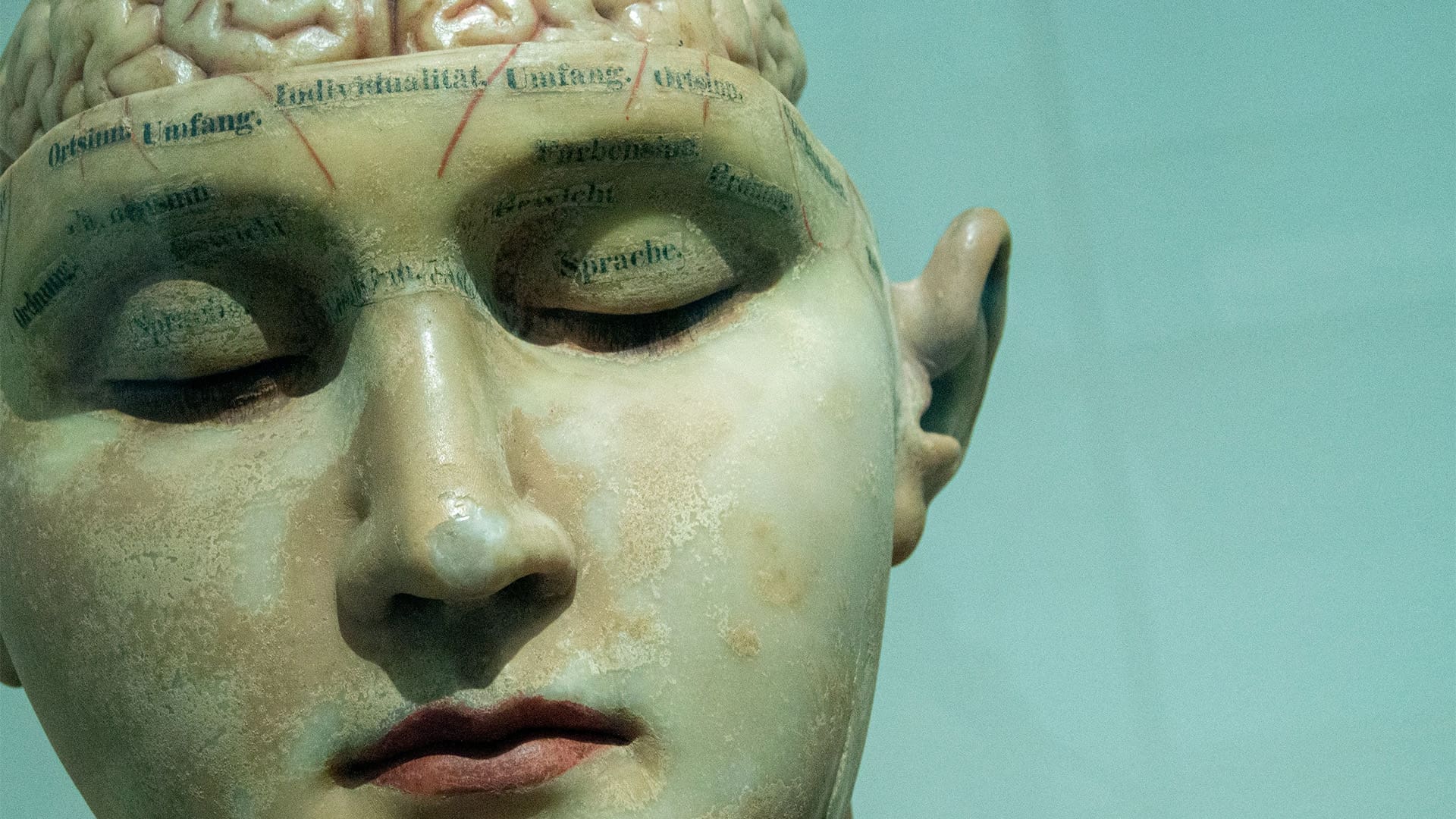

What the speaker (and perhaps the audience) had forgotten is how intertwined bioethics and Christian theology were at the discipline’s inception. It may be too strong to say that bioethics in America began as an offshoot of Christian theology, but it is undeniable that theology was one of its primary conversation partners from the very beginning. One commonly cited point of origin for bioethics in the United States is Henry K. Beecher’s “Ethics in Clinical Research” (1966)—a paper that, in the course of developing the informed-consent standard for human experimentation, quotes Pope Pius X. Two years later, the Harvard ad hoc committee on the determination of death theorized the concept of brain death in order to acquire more organs for transplantation. The Hastings Center published the first edition of its bioethics journal (now called The Hastings Center Report) in 1973. In other words, major bioethical decisions were made and institutions founded quite recently, almost simultaneously with major Christian contributions to bioethical debate.

At the same time, Christian theologians were busy at work on the same questions. The Roman Catholic magisterium published Humana Vitae in 1968. Protestant Paul Ramsey’s The Patient as Person, first published by Yale University Press in 1970, began as the Lyman Beecher Lectures at Yale University in 1969. (The full and original name of those lectures was the Lyman Beecher Lectures on Preaching.) Ramsey was invited to Yale by the Protestant ethicist James Gustafson, many of whose students went on to become pioneers in the field of bioethics. Gustafson taught both Tom Beauchamp and James Childress, whose Principles of Biomedical Ethics continues to be the most influential textbook in the teaching of bioethics in America. Gustafson was also an adviser and trusted friend of Daniel Callahan, who was among the very first to theorize bioethics as a discipline. Yet very little of this theological history makes its way into bioethics courses in medical schools today. Instead, under the influence of the Beauchamp and Childress textbook, bioethicists most commonly seek to justify their claims based on four principles they view as universally accessible by reason alone: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. The thinness of these principles, as well as the indeterminacy of both their definitions and their relations to each other, generates interminable bioethical disagreement.

In Bioethics After God: Morality, Culture, and Medicine, a misbegotten if earnest attempt to reframe the discipline from within the standpoint of traditional Christian morality, Mark J. Cherry argues that the root of this disagreement lies in the unmooring of bioethics from theology: “The remaining background framework of public Christian culture in the West is collapsing. The dominant secular culture that is emerging rejects both God and the idea of transcendent canonical truth. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, we are witnessing the emergence of a post-Christian, fully secular culture that eschews any point of ultimate truth or meaning. The implications for bioethics are significant.” This is a story of elite secularization and the effect that secularization has had on the field of bioethics.

Cherry sees this development beginning with what he calls “weak thought”—moral reasoning without reference to God. He claims that without God, or a God’s-eye perspective on the world, there is no binding and objective morality. Rationalists of a certain kind might have hoped to find such a morality in scientific inquiry, but Cherry agrees with the postmodern critics of science, who see it as a culturally conditioned and relativistic project. So God is dead, and there are no substitutes for him: “Without God to provide a uniquely true point of view,” Cherry says, “morality shatters into numerous incommensurable moral perspectives, competing accounts of moral judgment, proper reasoning, and rational analysis.” Secular bioethics—by which Cherry means bioethics without explicit relation to God—is now just a “private moral perspective” rather than a universally accessible appeal to reason. Yet secular bioethicists make claims to a kind of universal morality in their judgments (in principle, everyone can and does agree to the four principles). Cherry wants us to see that this “universal morality” represents, in fact, only one possible view among various ethical perspectives. To mask this false consensus, secular bioethicists are prone to call on governments to impose a particular bioethical perspective as the law, forestalling arguments among moral experts. As a result, “contemporary culture appears ever more akin to the birth of a form of neopaganism,” a reversion to the brutal and vitalist Greco-Roman society that preceded it. The plausibility of this claim is heightened by the fact that ethicists outside Christianity make similar arguments. Peter Singer famously claims that the only reason most modern liberals believe that the profoundly cognitively disabled are persons and therefore ought not to be killed is the “sanctity of life doctrine,” which Christianity brought into the world. Because Singer denies that doctrine and that ethic, he argues that those with profound cognitive disabilities are not persons and therefore may permissibly be killed—as was common practice in the pre-Christian Greco-Roman world.

While Cherry’s critique of modernity so far will be familiar to many Christians, he has an idiosyncratic spin. As an Eastern Orthodox ethicist, Cherry includes much of mainstream Latin Christianity in his narrative of decline: “The Western High Middle Ages produced a culture with a quite different view of proper behavior and human flourishing from that of Christianity of the first five hundred years.” On this telling, scholasticism was a step in the direction of secularity because the scholastic method maintained “a staunch faith in human reason” that led to the gradual erasure of God brought about in the Enlightenment and modernity. Without scholasticism’s confidence in human reason, the argument goes, Enlightenment rationalism would never have been possible. So the origin of modernity’s moral confusion lies in Western theology’s centuries-long preference for “the weakness of rational philosophical analysis rather than a robust experience of God.” In place of the reason-based methods established by the scholastics and their heirs, Cherry proposes that bioethics adopt an ethic of divine command.

Divine command theory claims that what makes an action obligatory is that God commands it, and what makes an action forbidden is that God commands against it. The most persuasive versions of divine command theory claim that God is not arbitrary in these commands; he always commands in accordance with human nature. So the good is inferred from human nature, while the narrower categories of the obligatory and the forbidden are delivered by divine command. Yet this does not appear to be Cherry’s view. He leaves unclear the relationship between divine commands and the rational status of those commands. Because he often pits obedience to the God who commands against attempts by human beings to reason about the goods at which bioethics ought to aim, readers are left with the impression that the version of divine command that Cherry endorses is a fideistic one. In such a version, the commands of God are inscrutable by human reason, and humans must simply obey them without attempting to discern the reasons that underlie the commands. Because “we must first come to know God in order to know the content and meaning of His commands,” Cherry is skeptical that “such deep disagreements will be finally resolved absent proper conversion and repentance.”

Hope for revival is not a political strategy, and until the lions lie down the with lambs, a society needs some means of adjudicating the disagreements between them.

It is true enough that conversion and repentance would be good for the project of living together in civil society. But even if Christians were to agree about what God has commanded medical professionals to do, there remain lingering questions about how much of that morality can be permissibly enshrined in the law. That the law cannot forbid every vice or command every virtue is a principle shared by both Aquinas and Locke. One way modern democracies deal with the problem of moral disagreement is to detach legality from morality and enshrine as law only those moral principles around which there is a sufficient, though never total or perfect, consensus. In fact, one plausible explanation for the origin of modern liberal democracy is as a kind of state-enforced truce between medieval and early modern Christians, who all believed in the same God but disagreed violently with each other about what God required of them. This explanation suggests that a simple return to belief in God and God’s law is unlikely to result in widespread moral agreement. Hope for revival is not a political strategy, and until the lions lie down the with lambs, a society needs some means of adjudicating the disagreements between them.

One proposal for such adjudication is a regime of secular public reason, in which religious views are confined to the private sphere while society’s common life is conducted in purely rational terms that are, in principle, open to all, no matter their broader philosophical or ethical commitments. But Cherry is keen to argue that allegedly comprehensive moral views such as utilitarianism or Kantianism are no less sectarian and parochial than religious views.

He is correct. Defenders of public secularity have argued that it is a kind of offence or insult to bring into public deliberation reasons that are unique to private faith. But this argument is undemocratic, asserting that secular ethical reasoning is universally accessible while arbitrarily weeding out religious arguments. In a democracy, everyone brings their sincere reasons into public and presents them for consideration, cross-examination, and approval. So it makes tactical sense for ardent supporters of private moral views to articulate their views in language accessible to as many as possible, in the hopes of thereby consolidating a democratic coalition.

A Christian might therefore argue that she believes euthanasia is wrong because human beings bear a special sacredness as God’s gift. She should say so out loud in public. She should also be aware that because not everybody shares the assumptions underlying her view, the explicitly Christian version of the argument might not be very persuasive, even if it is true. So she should then show how her preferred policy overlaps significantly with the ethical views of those with whom she speaks. To skeptics of neo-liberal economics she might say that euthanasia is almost certainly going to be factored into calculations of health-care expenditures, with the easily foreseeable result that it will be cheaper on the public coffers to nudge the most expensive cases of sickness into an early death, allegedly with dignity. To disability advocates she should observe that the disabled will almost certainly be disproportionately pushed into ending their lives by a society that already fails to value those lives rightly. This offering of multiple, overlapping reasons is one way democratic coalition-building works. It does not solve but it does ameliorate some of the difficulties faced by widespread ethical disagreement.

Another difficulty with Cherry’s proposal to govern bioethics by an ethic of divine command is that there are not, in fact, that many divine commands that guide bioethical reflection and action. Much of the confusion marking contemporary bioethics, Cherry rightly notes, arises from the fact that bioethical reflection cannot keep pace with technological innovation. But even if it could, God has not promulgated any particular moral teaching about many of the issues bioethicists are concerned about.

One of Cherry’s own examples is the question of brain transplants. “Assuming that it is a successful head transplant . . . does the personal identity of the head donor survive the transplant?” There are further complications: “What about cases of cross-sex brain transplant? Would a brain be able successfully to integrate with a body of a different sex?” These are excellent questions, and certainly worthy of careful consideration before any doctor decides to attempt such a procedure. But it is unclear how such an issue would be solved by the divine commands we have. And Cherry does not help the reader solve the puzzle. Instead, he simply asserts a stark dichotomy between weak thought and traditional frameworks: “For bioethics framed within the limits of weak thought, since concepts of ‘male’ and ‘female’ are looser and more historically, socially, and culturally derived, what it is to be gendered female or male will depend, at least in part, on the choices of persons. Within traditional frameworks that recognize the existence of a fully objective and binding point of view, the science and metaphysics of what it is to be male or female will be fully grounded rather than socially constructed.” But this is to change the subject, not answer the question.

Cherry’s method in general is to point to a pressing bioethical disagreement, assert that the disagreement arises because of “weak thought,” and then assert, without substantiating the argument, that only a “contentful, binding morality” can solve the question—but then he rarely says how the contentful, binding morality would use divine commands to resolve the issue.

These conundrums are still in the future and are thus still speculative. Other cases of bioethical decision-making, however, are of more immediate relevance. Consider the determination of death. For most of history, death occurred when the heart stopped. Only in the twentieth century, with the advent of mechanical ventilation, could the heart be kept pumping more or less indefinitely. This difficult fact (combined with the need for more organs for donation) led Harvard scientists to propose whole brain death as another way to be dead, despite the circulatory system’s continuation through artificial respiration. A person can now be considered dead when all activity is thought to have ceased in the brain and brain stem, irrespective of whether the heart is still perfusing the body with blood. Though Cherry does not address this case study at any length, it is no speculative bioethical issue; it arises in most cases of organ transplantation and in the fraught cases of withdrawing artificial respiration at the end of life. Bioethicists will continue to debate whether brain death is a legitimate understanding of death. But what is clear is that the question will not be resolved by reference to divine commands, because God has given no special revelation about these matters. The resources both religious and secular bioethicists will need to use to adjudicate the question, then, are all the usual resources we often employ: principles and prudence together.

Even when there do appear to be divine commands, they need to be interpreted and interrogated to determine their applicability. Jehovah’s Witnesses reject blood transfusion on the authority of the multiple divine commands in the Bible to refrain from blood. The reason most Christians do not agree with Jehovah’s Witnesses on this issue is not that they deny the authority of the divine commands but that they disagree that the divine command prohibiting the ingestion of blood in the Jerusalem Council of Acts 15 was intended to include a prohibition of blood transfusions. The tools for determining the interpretation and applicability of the apostles’ command are the tools of philosophical and theological analysis.

Cherry does not address blood transfusions directly, but it’s an intriguing case study. While, as we have seen, there are pressing bioethical issues about which there exist no relevant, definitive divine commands, here is a case where there is a divine command, and yet it does not solve this issue. One subset of people thinks the command is decisive, but most Christians do not agree.

A simple reliance on divine commands in bioethical decision-making, therefore, is neither necessary nor sufficient to solve numerous disagreements. The set of philosophical and theological tools Christians in the West have developed and handed down, however, far from introducing liabilities, presents advantages to Christian bioethicists. That Christian bioethicists draw on moral resources other than divine commands prevents them from falling into the critique that they are advocating morally arbitrary principles. This appeal to a wider sense of reason then frees them to participate in broader public bioethical debate with secular bioethicists. Richard Rorty famously argued that appeals to religion in public moral reasoning are “conversation-stoppers.” Once a person has claimed “Thus saith the Lord,” he said, no further deliberation is possible. But if Christian bioethicists employ the same tools other bioethicists employ—concepts of human nature, difficult questions about the relationship between autonomy and authority, and so on—then there is no reason for them to ghettoize themselves into a sectarian conversation, nor allow themselves to be ghettoized by others.

What Christian bioethicists can contribute to these ongoing conversations includes fundamental studies of key ethical questions. What makes a good death? What is the definition of health? Should medical professionals be seen as mere providers of services or as stewards of a vocation? What would it mean for the physician and patient to be in covenant with each other and to act faithfully toward that covenant? These are precisely the kinds of questions that Christian bioethics has been considering since the dawn of the field.

But it is not only medical professionals who ought to give careful thought to such questions. Christians facing daunting medical diagnoses and decisions commonly consult with their pastors, priests, and other religious authorities. Those figures should begin by making bioethics a regular part of their reading. Simple proof-texting is inadequate to the complexity of the bioethical challenges that emerging technologies make possible; no amount of reference to the imago Dei will produce action-guiding principles about whether Christians should avail themselves of IVF or participate in normothermic regional perfusion, a cutting-edge, though ethically dubious, procedure to acquire donor organs. The irony is that many contemporary Christians have come to adopt bioethical positions outside the historic ethical teaching of Christianity precisely because they rely on a divine command ethic for making those decisions. Where the Bible is silent, so the argument goes, all is permissible under the doctrine of Christian liberty. But because technological developments motivated these bioethical issues, and those technological developments are foreign to the world of the Bible, Christians find themselves having quite little to say about emerging bioethical challenges if they rely too much on divine commands. Far from a way out of the moral impasse that marks contemporary bioethics, over-reliance on divine command theory will, in fact, make the moral thicket more difficult to escape. Cherry is correct to say that Christians should do their bioethics with attentiveness and obedience to the God who commands. But the God who commands is also the God who reasons.