Dietrich von Hildebrand (1889–1977) was a German philosopher known for his works in ethics, aesthetics, social philosophy, and the philosophy of religion. He was one of Europe’s most outspoken voices against Nazism and Communism. A convert to Catholicism, he had a profound impact on the thought and life of the church in the twentieth century.

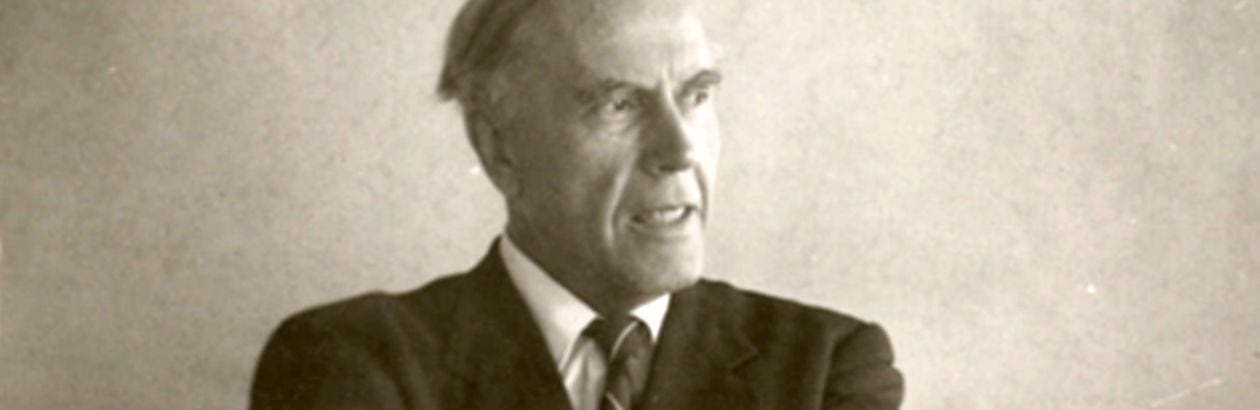

Professor Dietrich von Hildebrand

New Rochelle, New York

Dear Gogo—for that is what your family and friends always called you, the nickname you received in Florence, the land of your birth and youth.

You have been in my life since my earliest boyhood. You brought my parents together, my Austrian mother, who loved you so, and my American father, your devoted and faithful student. I myself “discovered” you when I was a young teenage violinist, devoted to an ancient art in a world often uncomprehending of beauty’s pull. Reading your luminous essay on Mozart introduced me to a high vision of the arts, not just as a mode of human expression but as a kind of “natural revelation” of God. But this was also the time I discovered that you had been one of the great opponents of Nazism. I had found not just a brilliant mind, but a man of great loves and tremendous courage whom I could follow.

You were, indeed, an original thinker, so much so that I have not hesitated to devote the past sixteen years to promoting your immense body of writing—which I firmly believe is destined to become a part of the perennial Christian tradition. But you were more than a searching mind; you were also, and perhaps above all, a witness—that is, a person so suffused in love of truth, goodness, and beauty, and indeed, someone who so wished to be “transformed in Christ,” that you spoke not just to the intellect but also the heart: to the student of books and the student of life, to the person just setting out on the journey and to the person already well along the way.

I think of your conversion to Christianity when you discovered the beauty of the saints and the radiance of the God-man. We Christians today can be so timorous in making our faith known beyond the walls of our churches. But you, with contagious joy and an irrepressible desire to share the wellspring of your hope, inspired innumerable conversions to Christ. To think you had more than one hundred godchildren! And yet the faith you lived was anything but watered-down clichés. To follow Christ brings fullness of joy but requires the “readiness to change,” as you would put it, enduring all things “in His name.”

I think of the “evenings” you hosted in Munich and later in New York City, open to all, regardless of social station. Wherever you went, you were always drawing people into community! Your “liturgical evenings,” in which you spoke on the day’s Scriptures, attracted people who wished to live the gospel fully. Your “cultural evenings” were devoted to music and poetry. What I would give to have been present just once!

I think of your fierce battle against Nazism. When Hitler came to power in 1933, you did not flee Germany in fear but chose to leave your homeland for a completely uncertain future; to serve, as you proposed to the Austrian chancellor, as an “intellectual officer” in the battle against Nazism. The journal you founded in Vienna in 1933, perhaps the leading forum for the intellectual resistance, was so outspoken that Hitler demanded its closure. Your public resistance also fortified many ordinary Germans and Austrians who were uncertain how to navigate the turbulent times. You had a rare gift for the discernment of spirits. When fear of the Red Threat led many to see in Nazism a counter to Communism, you saw in them evil twins, regimes united in their totalitarianism, racism, and atheism. And all of this you bore with moving serenity, trusting in God’s providence, even as you lived in constant danger of assassination.

I think of the enduring wisdom your writings offer us today. To a world desperate for love but convulsed by fear of rejection and suffering, you remind us that love is always a heroic gesture. To a world searching for meaning, yet often trapped in the most mundane of escapes, you help us see a world full of signs of transcendence, especially in beauty. To those who long for true worship, you remind us that religious sentiment alone does not suffice but that we must nurture reverence and adoration.

I think of the nobility with which you bore the illness of your last days. And I fervently hope that when my own time comes, I will be able to pray, as you did on your deathbed, with that inextinguishable fire of faith: Et jube me venire at te!—“And bid me Lord come unto Thee!”

John Henry Crosby

Hildebrand Project

Steubenville, Ohio