O

On a Saturday morning in April, Andrew Christian clocked out after working a double at a FedEx warehouse. Night shift as usual, as he’d done since dropping out of high school a few years prior. Job was good, pay was better. He was only twenty-one, but the hours had aged him prematurely. He didn’t smoke or drink like he used to. But when he’d stop at the corner store to pick up cigarettes for his fiancée’s father, no one carded him anymore.

Once home, he needed to sleep a few hours before hitting the road again. Didn’t want to endanger Abby, his fiancée, driving her up mountain roads when he was sleepy. The drive wasn’t short either, from the plateau of the Piedmont to the Blue Ridge Mountains. On the way Andrew would pass his hometown of Statesville, North Carolina, at the crossbar of I-77 and I-40. “Well, technically Olin, but nobody knows what Olin is. . . . Nothing but farms and Amish people.”

They were heading to another place nobody had heard of: Spruce Pine, North Carolina, population 2,381. Some friends and I had also driven there, from the opposite direction, for the same event: the Rural Revival Project, a street festival series with a mission to bridge the “economic and cultural gap” by “using music to strengthen communities, boost local economies, and reconnect rural areas with the rest of the country.” It’s the vision-in-progress of Chris Lunsford, a factory worker turned folksinger when his song “Rich Men North of Richmond” (recorded under his grandfather’s name, Oliver Anthony) blew up online. Now he’s also a travelling minister of sorts.

This would be Andrew’s first concert. “I don’t like all the noise and rowdiness and everything that comes with that.” But this was in a quiet town on Main Street, just “people coming together and singing about what they believe in.” The music was real. Andrew would sing Anthony’s music out loud and on repeat to keep himself awake on night shift. “There’s tears and there’s blood and there’s sweat behind those lyrics.”

The arc of Lunsford’s life mirrored his own: dropped out of high school, drank, worked, smoked weed, procrastinated. “Until he had his come-to-Jesus moment in 2023,” Andrew explained. “Basically said, ‘I’m going to go sober for thirty days if the Lord will give me something to sing about, something that’ll encourage people.’”

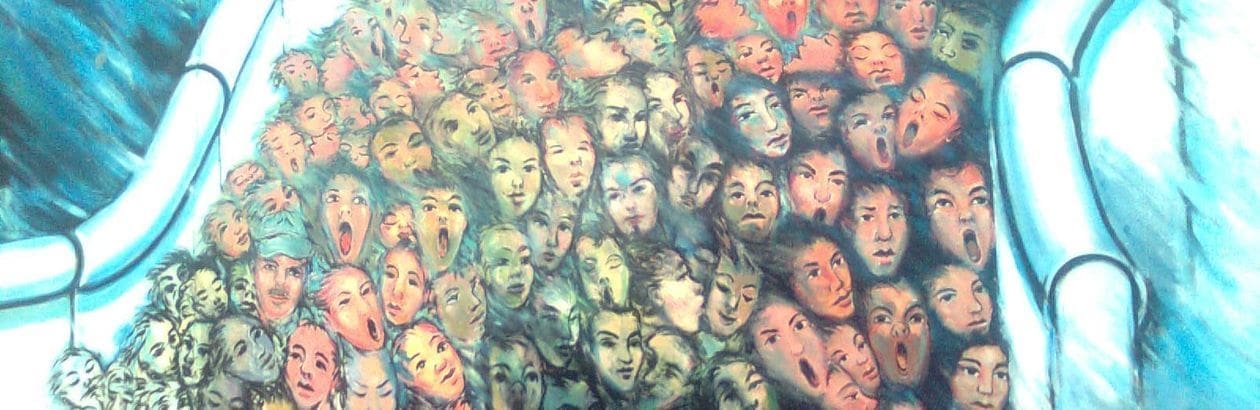

We were moths to the flame of Oliver Anthony and his music and message—a microcosm of what had happened all over the country, and indeed the world, when “Rich Men North of Richmond” went viral. Recorded in the woods and uploaded on YouTube by a West Virginian construction worker with a passion for finding Appalachian talent, in two weeks “Richmond” had more than 24 million views. It climbed the Billboard charts to do what literally no artist, let alone an amateur who had never played a concert, had ever done before—get to the number-one slot with no prior chart history.

The people “Richmond” reached—who’d blasted it from the cabs of pickups and through earbuds on long shifts—were being drawn out from the little places, over the country roads to this unsuspecting place in western North Carolina whose Main Street just six months prior had been covered by nine feet of water after Hurricane Helene. I met self-described “country boys” coming from Massachusetts on their motorcycles, a podcaster from Texas, an herbalist from Canada. Winston Marshall of Mumford and Sons fame was here from London.

But mostly the thirty-five hundred people were from here. Many I met were surprised that I’d driven seven hours. Like the young married couple with a baby I met in line while waiting for pork and beans, who met working in a restaurant, after she’d already swiped left on him on Tinder. “I saw he had a nose ring so I thought he must be some flamin’ liberal,” she laughed.

The crowd wasn’t necessarily left or right, more mixed than that, more politically agnostic, though conservative if pressed about it. The friends I travelled with had met in a bar in deindustrialized Terre Haute, back when they were both Bernie supporters.

Lunsford himself is neither a Republican nor a Democrat. “It seems like both sides serve the same master. And that master is not someone of any good to the people of this country,” he said in a video before “Richmond” went viral. On Jordan Peterson’s podcast in 2023 Lunsford talked about how hopeless it made him feel to see people divided. “We find fault in each other instead of finding common ground,” he said. “Everything has become politicized. Everything is about one party or one person trying to hold some moral high ground over the other just for the sake of being able to point their finger down at them.”

His lyrics about welfare were misunderstood by those who saw him as punching down on the poor rather than punching up at the system, underestimating the anger that some people on welfare themselves have toward the system. They feel trapped by programs that penalize work and marriage—that go away as soon as you get that promotion, as soon as you settle down with the one you love, as soon as you try to do better for yourself. I’ve noticed that quietly and without fanfare Lunsford seems to have changed the lyrics—from “milking welfare” to “stuck on welfare”—to better convey his intended meaning.

I was at this Rural Revival as an Oliver Anthony fan. His album Hymnal of a Troubled Man’s Mind was the soundtrack while I wrote a piece about the young men on my street who’ve died of overdoses and suicide. There was a night I couldn’t sleep and listened to his album on repeat.

I was also here as a fan of the populist spirit. In 2010 my husband David and I moved to a small town in southwestern Ohio, divided geographically by hill and valley, new neighbourhoods and old separated by river and old railroad track. I went there as a conservative focused on cultural issues like marriage and family but was blindsided by the realities of economic inequality and the way that low-paying, back-breaking work with irregular schedules and few benefits makes it harder to form a stable family and to participate in church and civic life. Our older neighbours migrated here from Appalachia for union jobs that are now gone. I’m regularly scandalized by the class divide—by the way that “the poor keep hurtin’ and the rich keep thrivin’,” to borrow some of Anthony’s lyrics.

We became deeply interested in grassroots organizing and in populist movements. Michael Moore’s documentaries were popular at the time, telling the twin tales of deindustrialization and the hollowing out of rural America. Though this narrative was told more frequently on the left, we recognized its truth from the right. We could see the havoc it was wreaking on the very social fabric that conservatives rightly sought to protect.

As we wrote in First Things in 2014, there was a need for solidarity, for a cross-class movement to bring the concerns of the people to the fore, for suffering to be named, for ties to be forged.

It was our populist moment.

The word “populist” first appeared in 1891. A group of Kansas farmers coined the term on a train ride back from Cincinnati, where they’d just launched the People’s Party. This new political party sprang from tens of thousands of Farmers’ Alliances, local cooperatives in which small farmers—both black and white—banded together to provide an alternative to the monopolistic and predatory practices of the big corporations.

Is there such a thing as a populism of solidarity? A populism that is less like wildfire and more like a construction crew?

Fast-forward a century or so and populism has gotten a bad rap—as being a destructive nationalist, racist, xenophobic force akin to mob rule and prone to demagogic manipulation.

And so I also came to the Rural Revival with a question: Is there such a thing as a populism of solidarity? A populism that is not polarizing but pluralistic—that brings people together across divides instead of further dividing? A populism that starts with legitimate grievance but builds to active hope, not bitterness? A populism that is less like wildfire and more like a construction crew?

Friday

It’s hard to find the Bridge Church, an Assemblies of God church in Spruce Pine, tucked into the mountain on the other side of the North Toe River, not far from where the ball field was wiped out, just the scoreboard standing there in a field of mud. There is a sign outside the door about a baby shower and décor for the occasion, but volunteers in tie-dyed T-shirts assure us this is where a small group from various churches is gathering for worship and testimonies, and to pray over the weekend.

Dr. Michael Moore—the pastor, not the filmmaker—is facilitating. He happens to be Lunsford’s pastor; he baptized Chris in the creek on his property. Red-cheeked with smiling eyes, Pastor Mike has the ruddy look of a midwestern farmer, the casual manner of a country preacher, an evangelist’s zeal for the people of the streets, and a doctorate in evangelism and church planting from Liberty University. He grew up being dragged along to the bar by his alcoholic father.

Pastor Mike takes the mic, an American flag behind him and TVs displaying shimmering turquoise bubbles, and opens with a question: “When was the last time you had someone over for dinner?” He quotes J.D. Greear making the point that diversity in the church will happen only if it first happens in our living rooms.

The guy next to me fiddles with a package of gum, unwrapping a green stick from its foil and offering me a piece before Pastor Mike calls him up. He motions for his wife Brittany to join him for moral support.

In 1995, at the start of the opioid epidemic, Brian was fifteen years old and in a car accident. His doctor prescribed oxycodone. In 2023 he and Brittany were living on the streets of Kensington, Philadelphia, one of America’s most drug-addicted neighbourhoods. At that point in his life, Brian no longer believed in God, yet he admits the irony that he was “still blaming God for everything.”

In a strong-webbed daily-life accompaniment that I’ve rarely encountered, Pastor Mike, on mission in Philadelphia, met Brian and Brittany and helped them get to rehab in Viriginia near his church. There they got their lives back. Brian says it was a John Piper sermon about this “light and momentary affliction” that helped him find purpose in his suffering. “I try to think of that often. That gets me through.”

Their story reminds me of two women on my street who got addicted to pain pills after being prescribed them postpartum. One of them later started using heroin and lost custody of her three children. The other spent the first ten years of her child’s life dependent on Percocet and Vicodin.

My neighbour senses that elites don’t care. “They got their money,” she says. She reminds herself daily, “This is not my home. I’m just passing through.”

She’s an Oliver Anthony fan and would have come with me if she didn’t have to work weekends. One of the great challenges of a truly populist movement is this: the people who are the rightful heirs to leadership of the movement—the ones with the life experience and a disproportionate share of sufferings—are often too busy just surviving.

But it’s one of the things that excites me most about the Rural Revival Project—it is not your typical non-profit. I can imagine it becoming a way to develop working-class leaders who form working-class institutions to solve working-class problems.

Brian and Brittany are now here as ministers themselves.

Brian and Brittany, pastors.

Saturday

The light is exceptionally bright this morning, the sky vivid as I walk to the Rural Revival, where local craftsmen are selling their goods alongside blacksmith and pottery demonstrations. I can’t stop thinking about Brian and Brittany. I can’t stop thinking about my town. I see the paint peeling on the houses where men have died deaths of despair. I know people who’ve escaped addiction with their lives, and those who haven’t. Whole worlds torn apart—worlds barely acknowledged by the mainstream—large worlds, common worlds. Yet unseen. Where is the reckoning?

As I’m brooding, I see them walking in front of me.

“Thank you so much for sharing your story last night,” I say over-eagerly, catching up.

When I start to say more, I unexpectedly break down crying. I’m taken aback—I hadn’t realized how much I was feeling this.

Brittany hugs me until I manage to venture, “Talking with you is like talking to someone who’s been resurrected from the dead.” Brittany prays aloud for all of us. When we open our eyes, I squint in the intensity of the sun.

Being here, I’m surrounded by people who know these same worlds and yet are keeping hope, casting vision—literally growing things, making things. Saturday afternoon’s “Truth Talks,” curated by documentary filmmaker Graham Meriwether, focus on self-sufficiency, faith in hard times, and local agriculture and manufacturing. The lineup is eclectic and intuitive, like the frequently voiced aspiration to own “a trailer in the country.” I recall something my neighbour told me: at root of a lot of modern suffering—the reason it’s easy to fall prey to addiction—is that we humans are not living as we were created to live. She talks about being barefoot in the grass, food sourced locally and eaten whole, less screen time and more life with real people in real places. Things echoed here.

At the first talk, “Healing on a Homestead,” Lunsford remarks, “There are so many people who could and probably should do things together but don’t because of how polarized we are. It’s important that we all get to know each other and get together like how we are here.” Later a panelist makes the point that he could either spend a lot of energy being frustrated at a bureaucracy or “take that energy and grow food.”

Panelists do have things to say to elected officials. Two of them, a farmer and a T-shirt manufacturer, have testified before Congress. Lunsford has a connection with Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who helped inspire a vision for his farm as a healing centre for veterans.

But the overall thing seems more in the ethos of the old American thrift ethic: self-help with a helping hand, individualism tempered by cooperation, the very best of the American spirit. It was the same sentiment I encountered at a conference the month before, at the historically black school Hampton University, when a panelist called for civic engagement and personal responsibility, saying, “Nobody is going to save us but us.” It sits in a funny but beautiful kind of tension with the anthemic nature of “Rich Men North of Richmond.”

Lunsford’s performance of the song, the last song of the festival, moves me. The crowd had been enjoying the music tamely; now they are upright. It’s the only time I’ve been in a group of working people all together in one place, singing at the top of their lungs, phones in the air, a collective and cathartic outcry.

Livin’ in the new world with an old soul

These rich men north of Richmond

Lord knows they all just wanna have total control

Wanna know what you think, wanna know what you do

And they don’t think you know but I know that you do

On the Lex Fridman Podcast, Lunsford describes the populist energy at his packed concerts in 2024 as “revolutionary” and then confesses, “I wasn’t necessarily even excited that ‘Richmond’ did as well as it did. It was like, in a way, it was almost like alarming that it did so well.”

Andrew and Abby are also in the audience. But when I talk to him later, he tells me that something about “Richmond” makes him slightly impatient.

“I’m an action guy,” he says, “so something like ‘Richmond’ . . . that’s good and all, that’s the first step to it. But if there’s no action after that, then talk is talk. Walk is walk.”

Andrew came to the Rural Revival weekend with a mission. His church has a brand-new food truck, and he’d like to bring it to future festivals, handing out free food and tracts.

“I agree there needs to be reform,” he clarifies. “A lot of people are set up for failure.” Like the people he’d been talking to at the festival who were good people but struggling. “They’re trying to hold a family together, and they’re barely doing that.”

Andrew used to visit a homeless shelter biweekly and got to know a guy well enough to have a tough but honest conversation. Andrew had been in a similar situation himself, when he was couch-surfing and sleeping in his car. “As a man, sometimes we just got to sit and look at our situation and say, ‘I know this sucks. . . . But there’s no one that’s going to change it but me.’ We got to pick ourselves up by our bootstraps and just figure it out—not only just by yourself, but as a community and band together.” Self-help, yes, but with that helping hand.

His outlook reminded me of how Lunsford told Joe Rogan a couple weeks after “Richmond” went viral, “I’m not an anthem-song kind of guy.” He was initially resistant to recording “Richmond,” even asking to take it down shortly after it was posted.

Lunsford believes what he sings in “Richmond,” born of years spent talking to blue-collar people on job sites as an industrial salesman and feeling that weight. But he wants to be prudent about its power. “It’s like, how much fire am I willing to play with?” he asked.

It reminds me of something Representative Marie Gluesenkamp Perez, a Democrat and auto repair shop co-owner in Washington’s third district—one of only a few districts in which both a Democrat and Trump won in 2024—said at a recent townhall to angry constituents: “Being angry, being loud feels good. But is it productive?”

“I would argue the way you put the fire out is by actually going and building community,” she says. Philosopher Hannah Arendt makes a similar point about the creation of a “common world” as the surest way to resist loneliness and authoritarianism.

Lunsford thinks there’s something deeper that people are responding to in “Richmond.” “Those crowds that show up, maybe they do like my music, but I also think they’re there for something,” he says. “There is something bigger about it.”

He muses that “it resonated with people who voted differently than each other, which is probably pretty terrifying if you’re in the business of keeping people divided and angry at each other. So it was one of the only times that I can think where there was that much of a sense of unity.” The other time was in fourth grade, when 9/11 happened, he says. “People just put everything aside there for a little while.”

It was the same thing that happened, momentarily, in western North Carolina after the hurricane. In the crowd that night before Oliver Anthony performed, I met Callie Farmer and Ray Ortiz. The two of them leaned against the red brick of a Spruce Pine business—Callie’s long white dress a vivid contrast—talking like old friends, straw hats shading the slanting evening sun. But they’d met only months earlier, after the disaster. Ray, a farmer and carpenter who lives on the mountain, was driving wherever he could on his ATV, searching for people in need of help, finding those for whom help had come too late. He was part of a massive, un-orchestrated civilian response that astounds me the more I learn about it.

Ortiz tells me that in the initial weeks after the storm, people set aside all the typical divides, new-found unity driven by urgency and perspective. The storm did not discriminate between migrant communities and those whose families had been on the mountain for generations. Trump voters and undocumented migrants worked side by side to clear the roads.

Because the FEMA response was slow, a flowering of grassroots groups dedicated to mutual aid filled the void, like the Swannanoa Grassroots Alliance, which still meets several times each week and engages over seventy organizations. Callie founded the United Carolinas Cavalry. “We’re all nobodies,” she tells me. “I’m a small-town girl. . . . None of us had ever had any experience with disaster relief. We all just saw the need and we jumped in.” Callie sees both devastation and beauty. “We finally got to a point we all knew that in order to be the most effective and be able to help the most people, we all needed to work together.” Lunsford was part of response efforts, which inspired his talk at ARC, “The Nobodies Will Rise.”

There is a populism that ends in bitterness, and there is a populism that finds a way.

“Richmond” without Rural Revival is explosive talk, a revolution of words. But Lunsford—like Andrew, like fellow “nobodies”—is an action guy. That’s why this weekend in Spruce Pine, money is being spent at local businesses, a house is being rebuilt, free packets of seeds are being distributed, and documentary footage to tell local stories is being filmed—with other behind-the-scenes efforts not advertised but ongoing.

There is a populism that ends in bitterness, and there is a populism that finds a way.

This priority for the practical reminds me of a principle Pope Francis was fond of repeating: “Realities are more important than ideas.” Ideas alone, he believed, are insufficient, “capable at most of classifying and defining, but certainly not calling into action.”

It’s one of four principles Francis outlines in his 2013 apostolic exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium (“The Joy of the Gospel”), a passage David and I have returned to again and again. Francis hoped the principles might be a guide for “the building of a people where differences are harmonized within a shared pursuit.” We read them as Francis’s guide for a populism of solidarity.

There’s an emphasis in his thought on initiating processes and widening and sharing, rather than narrowing and dominating, the space. Which leads to his second principle: “Time is greater than space.” An important implication is that we can “work slowly but surely, without being obsessed with immediate results.”

“Unity is greater than conflict” is the third principle. There are three ways of dealing with conflict, Francis says: to ignore it, to become trapped by it, or the third way—to “face conflict head on, to resolve it and to make it a link in the chain of a new process.” This enables “communion amid disagreement” and allows us “to see others in their deepest dignity.”

Importantly, this third way “is not to opt for a kind of syncretism, or for the absorption of one into the other, but rather for a resolution which takes place on a higher plane and preserves what is valid and useful on both sides.”

Finally, Francis proposes, “The whole is greater than the part.” This principle invites us “to broaden our horizons and see the greater good which will benefit us all.” At the same time, “we need to sink our roots deeper into the fertile soil and history of our native place, which is a gift of God. We can work on a small scale, in our own neighbourhood, but with a larger perspective.”

Metalwork at the Rural Revival Project. Photo by Oran O’Carrol.

When a populist movement engages with real problems, initiates processes involving a wide range of people, and builds institutions for the common good, that populism can have “a pluralizing impulse,” as Harry Boyte put it in an interview with David and me. Boyte, who worked as a young man with Martin Luther King Jr. in the civil rights movement, is one of America’s foremost champions of a “civic populism,” which he defines as a populism with “a plural understanding of the people.” As he sees it, civic populism is rooted in “a politics of the people—not of parties, not of ideologies.”

You see this pluralizing potential with “Richmond.” I know an Ivy League academic who likes to scroll the comments on Anthony’s videos, struck by the number of black men reaching out and saying things like, “This is not a conservative or liberal song. This is not a white, black, or brown song. . . . It is OUR SONG, OUR ANTHEM.” Canadian rapper Dax is one of many who did stirring remixes. There is a world of reaction videos online crossing all kinds of divides—regional, racial, partisan. There are currently almost 220,000 comments on the original video, mostly working people from all over saying how much they relate. Like the Honduran American who commented, “I have two jobs. I work as a cook, then i go to UPS to load boxes. I barely see my 2 boys and I hate that more than anything. This song had me tearing up. We are the true disenfranchised.”

Lunsford told Rogan that people often stop him on the street to say that since hearing the song they’d started talking to people they’d stopped talking to because of politics, including brothers who hadn’t spoken to each other for six years because of a disagreement over Trump and Biden. The message of “Richmond” gave them common cause.

To have enduring influence, populist movements must work across dividing lines, eventually influencing elite institutions—their causes taken to heart by public servants and elected officials who institutionalize and sustain populist priorities, as happened in American politics in the progressive reforms of the first part of the twentieth century. The sobering thing, of course, is that populism can also have a polarizing impulse and become the handmaiden of partisan politics. A pitfall of past movements is that they often couldn’t overcome regional and racial divides, as historian Trygve Throntveit and Boyte point out: despite some early, grassroots examples of black and white farmers working together in the Farmers’ Alliance, racial and cultural differences ultimately stymied the movement as it organized into a political party.

I’ll never forget last summer driving on a dusty country road behind my sister, who is white, and her husband, who is black. A white pickup truck zoomed by us and then weirdly slowed its pace while on the wrong side of the road, sidling up to my brother-in-law’s van, dangerously close. I saw only arms gesticulating out the open windows, but the truck seemed packed with young men. They screamed profanities and called him a n****, then sped away.

A populism that condones or inflames such action is over before it’s even begun.

Sunday

Sunday morning there’s a guy with a guitar playing contemporary worship on the Main Street stage. My friends, the former Bernie supporters, wander off, uncomfortable in the cluster of us churchy people in the front putting hands in the air and singing love songs to Jesus. They wander back when Oliver Anthony starts singing hymns and gospel—“Amazing Grace,” “I’ll Fly Away,” “Three Wooden Crosses.”

Pastor Mike gives a message on suffering as “a diving board to greater things.” Perhaps Spruce Pine, with years of rebuilding ahead, is a beacon: “Maybe the world needs to see a community coming together! In a world so divided . . . Fox News has their version of the truth. CNN has their version of the truth. There is only one truth: the gospel of Jesus Christ.”

I am struck by the number of young men. Tough-looking guys with tattoos and snarky T-shirts, bikers and bodybuilders and veterans. Some of them are crying.

A large metal tub is filled, and one by one, thirty people spontaneously respond to the call to be baptized. Brian and Brittany and a line of others catch them in prayer. Representatives from local churches hand out cards to gather follow-up information. Lunsford beams from the stage while wet people shiver in towels.

After the service, a crowd surrounds Lunsford, who seems in no hurry, relishing the conversations with people eager to meet him. He has a mild, comfortable way about him like someone you’ve known awhile. I can see why the description of travelling minister suits him better than performer.

I have a note for Lunsford myself, though I feel shy about passing it. I summon courage as I watch a young man hand him a folded paper square, which Lunsford pockets as they talk, two unusually tall men with bushy beards, Lunsford’s red and the other man’s dark, the same shade as his black suit.

I introduce myself to the young man and the curly-haired woman with him. “What brings you here?” I ask.

“Oliver Anthony and I kind of have the same story,” he tells me.

The young man in the black suit is Andrew Christian, from Olin, North Carolina. Like Lunsford, Andrew grew up in church—he remembers being pinched by his mom if he wasn’t sitting still. But he was a mischievous kid, always into trouble, especially after his parents’ divorce and after his great-grandfather, the father figure in his life, developed dementia and passed in 2019. Andrew dropped out of high school, lived in his car and on friends’ couches, started drinking and drugs. He and Abby met working at Cookout, a fast-food chain in the Carolinas. “I wasn’t really going anywhere in my life. I was kind of just stuck in neutral. I hadn’t even got my GED yet.”

In April 2023 Andrew asked his older brother what he wanted for his birthday. “I tell you what,” his brother began. “If you just come to church with me, that’ll be your birthday gift to me. And in fact, I’ll even buy you dinner.”

“And I’m a cheapskate,” Andrew says to me, laughing. “So I went.”

As he walked out that morning and shook the pastor’s hand, the pastor asked him whether he was coming back the next week. Without thinking, Andrew said yes. “And I can’t lie to a pastor, so I showed up again and just really fell in love with it. Fell in love with that feeling again of being in church, and rededicated my life, and so did Abby, and then the rest is history.”

Andrew got sober. His older brother doubled as father welcoming the prodigal.

I ask Andrew what he meant by falling in love again with being in church.

“It wasn’t a feeling of great pride and joy,” he says. “It was a feeling of submissiveness and humbleness and what the Bible says—fear of the Lord.”

He felt convicted. “I knew what I was doing was wrong. I knew what I was doing was not the correct thing, but that didn’t stop me from doing it. I’d been wanting to clean up for a while, but I just never could.”

On that second Sunday, Andrew did what he had done as a kid—he went to the altar and prayed. “I just left it at the altar and believed that he would take care of the rest. I had to trust that he would take care of the rest, and he did.”

Andrew says there are no “magic words.” You can’t just “sit back, relax, kick your feet up. . . . It still requires getting your hands dirty.” But the first step, the thing that made the difference between success and failure, he says, was “coming to grips with the fact that I can’t do it by myself.”

Abby initially did not want to go to church with Andrew. Her parents weren’t churchgoers. “You know how church members are,” she would hear them say, alluding to hypocrisy and judgment.

“I have tattoos, and I didn’t have dresses, and I just didn’t feel like I looked the part,” she says. “I didn’t know all the songs. I just felt very out of place.”

But it was actually her mom who encouraged her to keep going. “I had really bad anxiety and depression, and I just felt like something was missing.” The second time she went, they were singing songs when a “weird feeling” came over her: “I felt safe and I felt sheltered.” She and Andrew built their community at this church; their wedding took place on a church member’s property overlooking a lake.

Andrew and Abby got married on a church member’s property. Photo: Henley Co.

It was that same summer of 2023, a few weeks before everything happened with “Richmond,” that Lunsford had his own come-to-Jesus moment. It makes me wonder, How many unknown others had such moments? How many are having them now?

“Belief in Jesus Rises, Fueled by Younger Adults” is the headline Barna gave to a recent study that found nearly thirty million more US adults say they are following Jesus today than in 2021. Between 2019 and 2025, “commitment to Jesus” jumped 15 percentage points among Gen Z men and 19 percentage points among millennial men.

“I just had a breakdown moment,” Lunsford told Rogan. He’d gone to the ER because of anxiety-related cardiovascular symptoms—he really thought he was going to die—and afterward remembers sitting in his truck crying. “I felt hopeless, like almost the way a child feels hopeless when they can’t find their parent. . . . I just didn’t have anything left in me.”

Then came the surrender:

I just decided, right then and there, I know I can’t do this anymore. . . . I just told God, just let me do it, and I’ll give all this shit up. I’ll give up the weed, and I’ll quit getting drunk, and I’ll quit being so angry about things. I’ll start over again, and I’ll make him the focus, and not me. I quit worrying about me, and I started worrying about what it is that I’m supposed to do.

Lunsford started reading the Bible privately, and then publicly at his concerts. He is not preachy (“My shit stinks,” he clarifies) but shares because he “found a lot of peace from this Book.”

Andrew doesn’t see this trajectory as coincidental. “Sometimes you have to get to that place.” He describes how King David was first a lowly shepherd. “In order to prepare David for the highest of highs, God had to send him to the lowest of lows. And you see that all throughout the Bible. That these characters in the Bible, in order to prepare them for great blessings, in order to prepare them for places of status and places where they’re going to have great power and responsibility, they have to be sent to a place where they have none at all.”

In August 2023, when Oliver Anthony was blowing up, Andrew preached his first sermon in a little country church.

There’s a philosophical concept, subsidiary focal integration, that I first read about in the pages of this magazine in an article on forgiveness by Esther Lightcap Meek. “We think we are staring at a mess of disconnected units of meaning,” she writes, “only to experience a surprise reversal—a fresh pattern comes into view; the clues are integrated into coherence. You’re picking out an odd pattern on a leafy woodland path when you suddenly see a copperhead snake quietly staring up from your feet.”

I’d come thinking about populism and left thinking about revival.

While I was looking at class division and despair, Andrew and others I’d met over the weekend were showing me something else. Andrew saw young men getting knocked flat on their backs by economic and social pressures, with nothing left to do but look up.

You’re seeing young men who just want to have—what was the American dream? To work, do it with your own two hands, and start and raise a family, and do it that way, do it the way our fathers and our grandfathers did it. . . . You’re seeing them realize that in today’s day and age, it’s really hard to do that.

And so you see them finally breaking down and getting to the point where they realize they need help doing it. . . . The Lord never intended life to be a solo mission. It wasn’t meant to be a Lone Ranger type of deal.

There is a genre of these young men—who seem to me different from the manosphere or MAGA or the manfluencers. They are more like the name of the men’s fellowship at Andrew’s church: BetterMan. These are men who are frustrated by economic and social conditions but not embittered by them, who believe in taking up their own agency but not in lone-rangerism, men who reframe suffering. Their sense of self becomes bound up in a sense of God’s mission for their lives. It’s how Andrew found himself building houses in Peru. How Lunsford found himself at the front of a movement.

Life opens up not to ease—you’ll always have to fight for what you get, Andrew said to me—but to surprising possibilities. Like Pope Francis’s “new and promising synthesis,” it is “the coming into being of a farther pattern, a larger reality, which catches up the older, splintered one within it and transforms it,” writes Meek. As Graham Meriwether puts it in a post about the origins of Rural Revival, “God works in mysterious ways.”

Hard times bring people to surrender, then to new life, a process capable of sanctifying many things, including the populist impulse. It becomes a populism of people who offer up their pain—allowing it to propel them forward, outward—rather than clenching it with both fists. Neither triumphalist nor embittered, it is powered by the humility and hope of people who have reached their end but found a way. Perhaps populism, then, can undergo its own conversion, one fire exchanged for another.