My path as a scholar to study and write about the Christian voices of the fourth century began during a bone-sorrowing year of closing doors. The graduate program and career I chose to please my parents—clinical nutrition—so sapped every morning’s energy and light, its non-stop patient teaching load an impossible mismatch with my introverted need for solitude, that I quit, with no idea what came next. At odds with myself, unsure even who I was, the ground kept shifting. Some changes were good; I “lost the friends that needed losing,” as Scottish folksinger Dougie MacLean puts it. Other losses stung, as when the gentle, kind, evangelical Christian man I thought I had been dating abruptly announced his engagement to someone else. Was it, I agonized, because I had told him the one true thing I knew about myself, that children were not in my calling? What did I want? How could my gifts, temperament, vocation fit with God, an icon of the incarnation in a vision for healing in creation? Restlessly, disoriented, I changed churches, booked a trip to India, turned to the one thing that kept me sane—reading church history—and wrote a letter to John Stott.

A friend who arrived from Stott’s London parish that year may have given me the idea. In those days my world was largely shaped by “evangelical” Christianity. (A fat lot of good that was doing me, I thought.) I’d grown up in a faith community that called itself the Missouri Synod Evangelical Lutheran Church. Both Lutherans and those following the more popular “evangelicalism” of the 1980s spoke of God in terms that best respected what I had experienced of one I could only call Jesus. So, I thought, weren’t evangelicals also supposed to engage tough, critical questions and (if only pretend to affirm) intellectual women who might actually read theology? John Stott—”the closest thing to an evangelical pope” according to his biographer Alister Chapman—might at least understand my question.

My question was this: Should I apply to graduate school to study church history? And, if so, might Stott advise me on whether in his view Harvard—or a British university—would best suit such a path? The letter was my “ebenezer,” hurling the lots at God. I gave Stott eight weeks to reply.

He took me at my word. His answer, early in the fall of 1987, was a carefully typed two pages that detailed pros and cons of both options.

“Dear Susan,” he wrote, “I hope that I may thus address you, and that you will accept my greetings and good wishes in Christ.

“I am glad that you felt able to write to me, although sad to read of your frustrations and dilemmas. I hope I may be able to help you a bit, although I am neither an academic nor a church historian!”

Help me he did. He summarized the British higher academic system, named specific universities he could recommend for church history and patristic studies, told me of the British Library (and how to get a reader’s pass), and suggested a scholar he thought I might write—even spelling out the address and what I should write on the envelope that it might actually be opened by that individual. Stott assured me that, were I to study in the United Kingdom as a doctoral student, “I am confident that there would be no bias against you on account of your being either a woman, an American or an evangelical.” It was, in short, a most optimistic and welcome post. In the end, it was his advice about Harvard Divinity School that I followed. Harvard had surprised me as the one local school with the best options for my interests. I’d grown up amid the bitter church politics of its faculty and students, and had my doubts. Still, Stott suggested, “I think you would be well advised to enrol at Harvard for a Master’s degree in church history. . . . Then, during this Master’s study, you could also (a) further test your gifts in the field of church history and (b) focus your area of interest more clearly among the possibilities you list.”

And it was so.

I begin this essay with a personal story because such is, I think, how any lifelong apprenticeship to a field of study begins, if it is worth its salt. Stott’s letter liberated me—evangelical or not—to enter a vocational apprenticeship with the fourth-century Greek Christian writers I have come to love who are called the “Cappadocians.” In addition, Stott’s model in advising women on vocational study in theology and church history stands as an often tragically needed vital witness for all today who continue to honour his memory and writings.

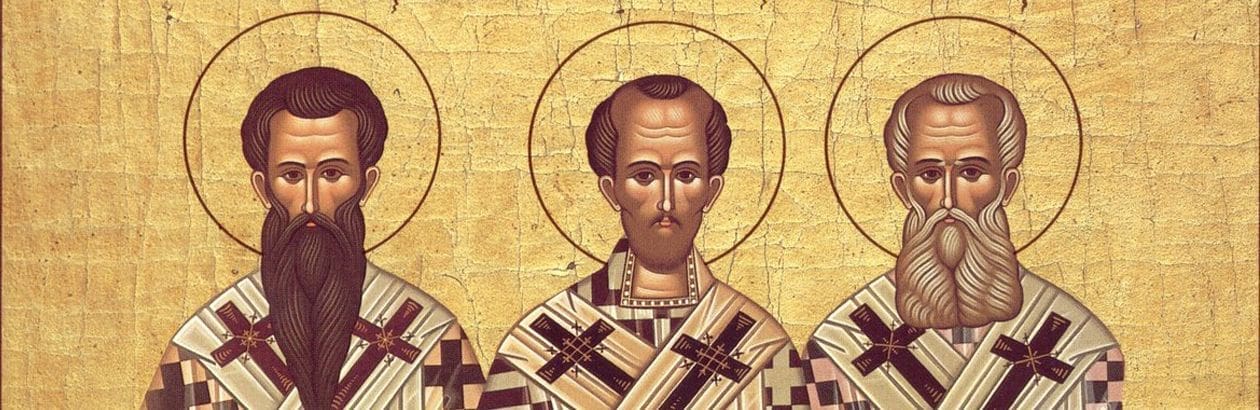

Protestants are probably the only Christians in the world who would count the Cappadocians as “forgotten.” This is ironic in light of their influence on the creeds that most traditional Protestants even today recite in church. The trinitarian theology of the ecumenical council of 381 shapes such statements in part thanks to one of its chief narrative architects (until he quit in a pique), the Cappadocian bishop Gregory of Nazianzus. While Gregory’s friend Basil of Caesarea is best known for championing the divinity of the Holy Spirit, it is Gregory who had the greater impact on Christian catechesis. As Christopher Beeley puts it in Gregory of Nazianzus on the Trinity and the Knowledge of God, Gregory is “the only theologian in Greek tradition comparable to Origen in terms of comprehensiveness, theological and exegetical acuity, and depth of vision,” one who showed “with practical and theoretical skill that the divine light of God, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, is the very meaning of the Christian life and indeed of all creaturely existence.” I am always cheered by Gregory’s affirmation, in his second theological oration, “What can mean more to the Word than thinking beings, since their very existence is an act of supreme goodness?”

The Cappadocians wooed me, however, not by theology or councils but through another “forgotten” thread: their commitment to social justice for the poor, starving, and sick. I spent the summer after Stott’s epistle intensively memorizing Greek rules and phrases, in sheer exasperation that the English translators had ignored both Basil’s three sermons on famine, wealth, and divestment, and his brother Gregory of Nyssa’s two sermons about the sick and homeless. If no one else could tell me what these homilies said, I would have to figure it out myself. “Despair not!” I inscribed in Greek on grammar notes; happily my French was good and French Catholic priest-translators beginning in the seventeenth century had left at least some sustaining crumbs in their homiletic trails that kept me going.

As I read and translated these sermons over the following decade, I was slain by their sheer honesty. Gregory of Nyssa, for example, seems to preach while shaking with the personal impact of his own visions. His sermons “on the love of the poor” fairly dance with their vivid appeals to Jesus’s parable of the sheep and goats in Matthew 25. “I have seen,” says Gregory in his first sermon. “Again I hold before my eyes,” he begins the second. Both visions evoke Gregory’s terror at damnation of those who ignore the moral mandate that entitles the poor to aid and justice, all who fail to look at the sick and hungry destitute and see an embodied Christ. “What does this mean for my vocation and everyday choices if it is true?” I asked myself. God knows, I would not last ten minutes trying to emulate Dorothy Day or Mother Teresa; was it enough to be a writer-scholar who at least tries to pray? Should I give my closet of designer shoes to the poor and join a monastery? Or could I embrace the advice of my friend Alice—a Christian social activist and, at eighty-six, the Peace Corps’s oldest volunteer—when she told me (years later), “You just keep writing and I’ll keep feeding the hungry!” Alice’s no-nonsense, shake-it-out good sense reminds me still that, like the Trinity and the Cappadocian family and friends, “charity/righteousness” (tzedakah) is about communal and neighbourly synergies. Social justice needs all our different gifts, working (if possible) together.

Basil of Caesarea knew this. Of course. So did his sister Macrina, and their baby brother Peter, all famous in Catholic and Orthodox Christian circles for their hunger relief, hospitality, and organized medical care for refugees and famine victims. Their brother Naucratius, more solitary, died while fishing to feed some old folks in the woods. We know less about three other sisters; at least one was supposed to be a nun until she ran off in love. Modern historians delight in these sibling tensions. Throughout the years since Stott’s letter settled into the dust of my files, my research and writing has been just one small cog in a thick moving wheel of studies and translations in English that introduce and entice modern readers to take up these—our—older spiritual siblings in faith.

When folks ask how we might learn from such friends for religious, spiritual, and academic practices today, I tell them a couple of things. First, read fairly and honestly. Do your best to understand history and context. Think empathetically—and critically—mindful of cultural difference, gendered blind spots and biases, hidden (and not-so-hidden) agendas. Ancient sermons, letters, canons, and even poems are not objective but rather constructions shaped through an interpretive lens. Second, read yourself fairly and honestly. We need to face ourselves as active agents, our limits and biases, our social, religious, and political purposes and agendas, if we are to be open to (perhaps radical) change in response to these voices, and if we wish to present them fairly to others. Third, think creatively about how such texts and messages—whether on pity, divestment, justice, or eternity—might be applied with both relevance and respect to the sphere of influence we inhabit in the here and now. Finally: maintain hope, wisely.

As someone who grew up—in both Canada and the United States —amid Camelot-like national optimism coinherent with a sense of imminent nuclear disaster, I am convinced that it won’t do us any harm to choose to be vulnerable to such voices from the past. They offer us glimpses of a long story that might, if we let it, inform our own journeying as thinking beings into global solidarity and hope.