D

Drive west of Washington, DC, past the hip neighbourhood of Clarendon and mansions of McLean and you’ll come to a small strip mall in Vienna, Virginia. Pull into the skinny parking lot, and you’ll see that, sandwiched between the Walgreens and Advance Auto Parts, is Jammin Java, an independent concert venue that might otherwise be mistaken for a strip club. The mornings bounce with babies and toddlers clapping along to children’s music shows. The evenings buzz with local songwriters and touring bands peddling their merchandise. I spent almost a decade living and playing music in northern Virginia, and Jammin Java was the hub.

The dark, sticky sweet bar was an inviting place for everyone—skater kids and lobbyists alike. So it was no surprise that the Washington Institute for Faith, Vocation, and Culture, a think tank, was hosting an event at Jammin Java. A college friend was the Institute’s program director at the time, and he knew I frequented the venue. They were anchoring the evening around the renowned painter Makoto Fujimura, and my friend asked if I would play an opening set for Mako’s address. Intrigued by the chance to mash my music with a think tank, I said yes.

The night of the event, my band and I settled into Jammin’s green room, a cornucopia of stickers plastering the walls. We took the stage, shared our songs, and scurried off. Mako was waiting in the wings, surrounded by cracked cymbals and backline drum gear. He turned to me and said, “Excellent job. Your voice sounds like it will thrive on the margins.” The margins? What aspiring pop artist wants to be told their voice will flourish on the margins?

In Mako’s seminal book Culture Care, he describes artists as “border-stalkers”—people who bob and weave along the margins of coherent communities, and in doing so become the menders of culture wars. He explores how creativity often emerges from these verges, cross-sections where novel things thrive.

It would be years before I would read Culture Care, but Mako’s intuition that I was a “border-stalker” intrigued me. His naming of a pattern in my artistic life, a pattern I often viewed as a weakness, opened up a surprise horizon.

What aspiring pop artist wants to be told their voice will flourish on the margins?

Collaboration Creates Courage

Two years passed, and after years of trying to balance my passion for music with my career as a US government intelligence analyst, I finally resigned from my job and moved to Nashville—the land of songwriters and record labels, crooners, and creatives. A friend helped me find an attic nook in a little yellow house shared with three other creative women. With rent at $250 a month, I could cobble together a living wage through live gigs, Uber driving, and voice-over work.

Writing and recording pop songs brought me into a wonderful world of indie artists and creative entrepreneurs. I rebranded myself as DANAE (my middle name), and my producer believed that our singles would be hits. Unfortunately, they weren’t. After three years of the starving-artist grind, I was facing broken dreams and a broken bank account.

Tearfully I cracked open with a dear friend, sharing my frustrations and bitterness, and with her introductions and coaxing, I took a role with a non-profit in New York City. Though my heart still longed for a career at the centre of the music industry, I needed to reset my expectations and recover the joy of making in a more stable context. My friend reminded me that Makoto Fujimura was also in New York City and known for bringing artists together. She gave me a copy Golden Sea, a stunning collection of painting reproductions and essays about his artistic approach. She encouraged me to dig in and reach out.

Empowered once more by someone else’s intuition, I wrote Mako, and we met for lunch. I shared about my struggles with Nashville’s music business and my fear that I had just wasted three years and a lot of money. He encouraged me that the time spent growing and refining one’s artistic voice and process is never wasted, that the fruitfulness of a creative season isn’t always seen right away. Our conversation converted my scarcity mindset into the strange yet far more generative cast of abundance, and in the coming weeks, Mako asked if I would write a song for his upcoming exhibit opening at Waterfall Mansion on the Upper East Side.

Me? Writing about a painter and visual art wasn’t something I’d done before. But Mako thought my voice and acoustic guitar would sound expansive in the marble walled gallery. Inside his invitation was the courage I needed to create.

Waterfall Embrace

The essays in Golden Sea gave me a conceptual and spiritual framing for Mako’s work. In “Splendor and Repose: Reflections on the Paintings,” philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff explores what makes Mako’s paintings so memorable, describing the medium of Japanese Nihonga: “With the exception of the gold and silver,” Wolterstorff writes, “there is no gloss; no sheen comes between the viewer and the rich, dense color. . . . Fujimura paints stillness.” Quoting T.S. Eliot, he concludes that Mako’s art invites us to “confront ‘the still point of the turning world.’”

This delicate insight set my pen on a journey to name the way Mako’s paintings make viewers feel, both inviting repose and offering a mystery that compels us to lean in. A ballad called “Waterfall Embrace” poured forth:

No gloss, no sheen,

Standing in the space between

No hurt, no pain

Shelters me from your sweet grace

Just you, with me

Light from you is my remedy

Just you, with me

Mending parts no one else can see

Being with you

I touch the still point,

of a tilting, turning world

Deep are my longings

But deeper your calling

A waterfall embrace of love

Soon the performance arrived. Triptychs of refractive mineral painting lined the walls. My parents nestled into front-row seats. A quiet hum from the twenty-foot waterfall washed the room. Butterflies in my stomach reminded me how much I loved performing.

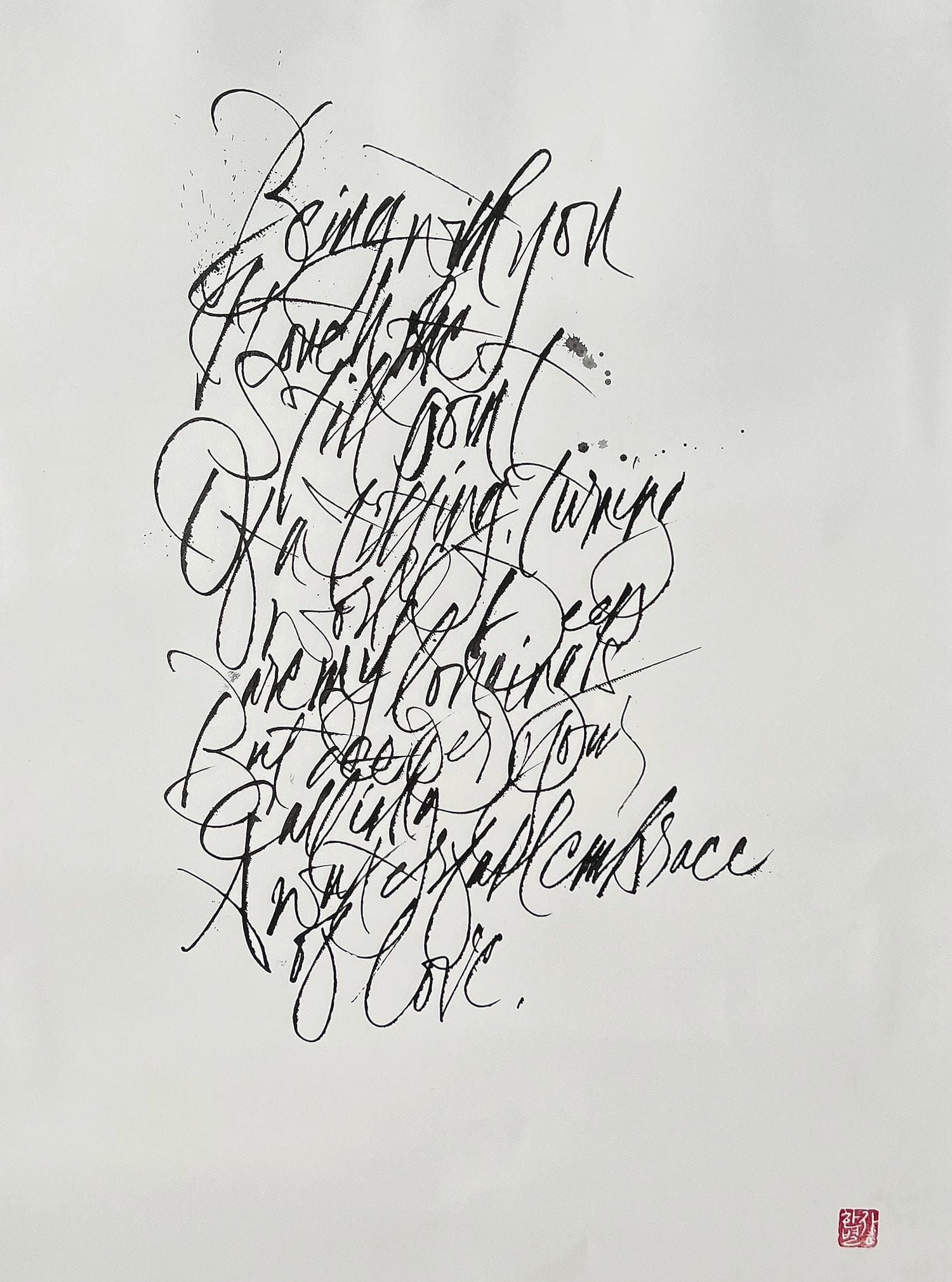

One of Mako’s friends, David Chang, an award-winning calligrapher, was so inspired by my song that he pulled out his materials and created in response. A mystical movement of lines and words, David’s calligraphy let me see my song with new eyes, hear my voice through a new medium.

Calligraphy by David Chang

The experience sparked a second collaborative friendship. Already both co-journeyers with Mako, David and I discovered a shared desire to follow the creative intuitions of the Holy Spirit and the Muse as we worked. I wrote more songs inspired by Mako’s art, and David would often give the song a shape with his pen. Our trust was deep, the joy wide.

Through my work with non-profits, I commissioned David to create numerous gifts for world leaders, ranging from a former CIA director and a US secretary of state to a former Polish president and billionaire real-estate developer. Each time, we would imagine the person and the moment, and then I would trust David’s listening spirit to create.

One time we collaborated to host a sixty-person VIP dinner for the South Korean ambassador to the United Nations back at Waterfall Gallery. A king’s table laced with linens stretched one hundred feet down the gallery with Mako’s paintings lining the walls. It was late 2017, and tensions were at a boiling point between North and South Korea. Though the event’s purpose was to learn about South Korean political policy, placing it in an art gallery surrounded by the paintings of Japanese American artists expanded the spirit of the conversation. To close the evening, I presented the ambassador with a piece of art: a quote from him about the need to fight now for future generations written out by David and illuminated by Mako. When he saw it, the ambassador beamed and said, “You know I consider myself an artist too!”

In this growing circle of collaborative friendship, not only were doors opened one after the next, but I also learned that, by listening to the moment and trusting artistic intuition, we find the courage to create from a deeper, more mystical place, a place of originality and breath.

Lotuses and Mimicry

Alongside “Waterfall Embrace,” I wrote two more songs about Mako’s life and work. “Lotuses and Mimicry” adapted a short poem Mako had written about his father’s passing. The song intentionally pulled from the expressive and dramatic tones of Japanese Noh theatre. “Hear Me”—a dark and brooding lament—responded to Mako’s artist talk titled “Deep Calls to Deep.” Each song was stylistically unique, and they seemed to skip along the margin of a variety of genres. But Mako had an idea: we should record them and release a vinyl. The large paper sleeve provided a perfect canvas to frame the music. And Mako knew the perfect producer for the project: Daniel Smith.

Mako had met Daniel over a decade earlier and helped procure a grant for Daniel to build a studio at his home on the outskirts of Philadelphia. As a songwriter, producer, visual artist, and singer, Daniel had taken his avant-garde music around the world, playing venues as gritty as the Knitting Factory in Brooklyn and as sacred as the Cornerstone Festival in Illinois. Known for his piercing falsetto, eight-foot “fruit of the Spirit” tree costume, and early work with Sufjan Stevens, Daniel didn’t do mainstream music. He chased the core of a song down and pinned it to a place of authentic expression, wherever that might be.

Mako, Daniel, and I set sail into a week of recording five songs for Lotuses and Mimicry. As a producer, Daniel never asked the question, “What would make this catchier?” or “Where can we add a hook?” Instead, we talked about the stories behind the songs, their moments of inception, and the way the music was mending us. Mako perceived a texture in my voice that hadn’t yet been captured in a studio. Like his own art, digital reproductions can’t fully render the full spectrum of nuance. So Daniel took time to explore alternative ways for tracking my vocals. His experimental approach freed me to try new ways of singing, more expressive and dynamic. So much of singing is mental, and Daniel created a spirit of freedom in the studio that let my full voice show up. In the end, we created a record that rested in a liminal space between jazz, folk, soft-rock, and Americana.

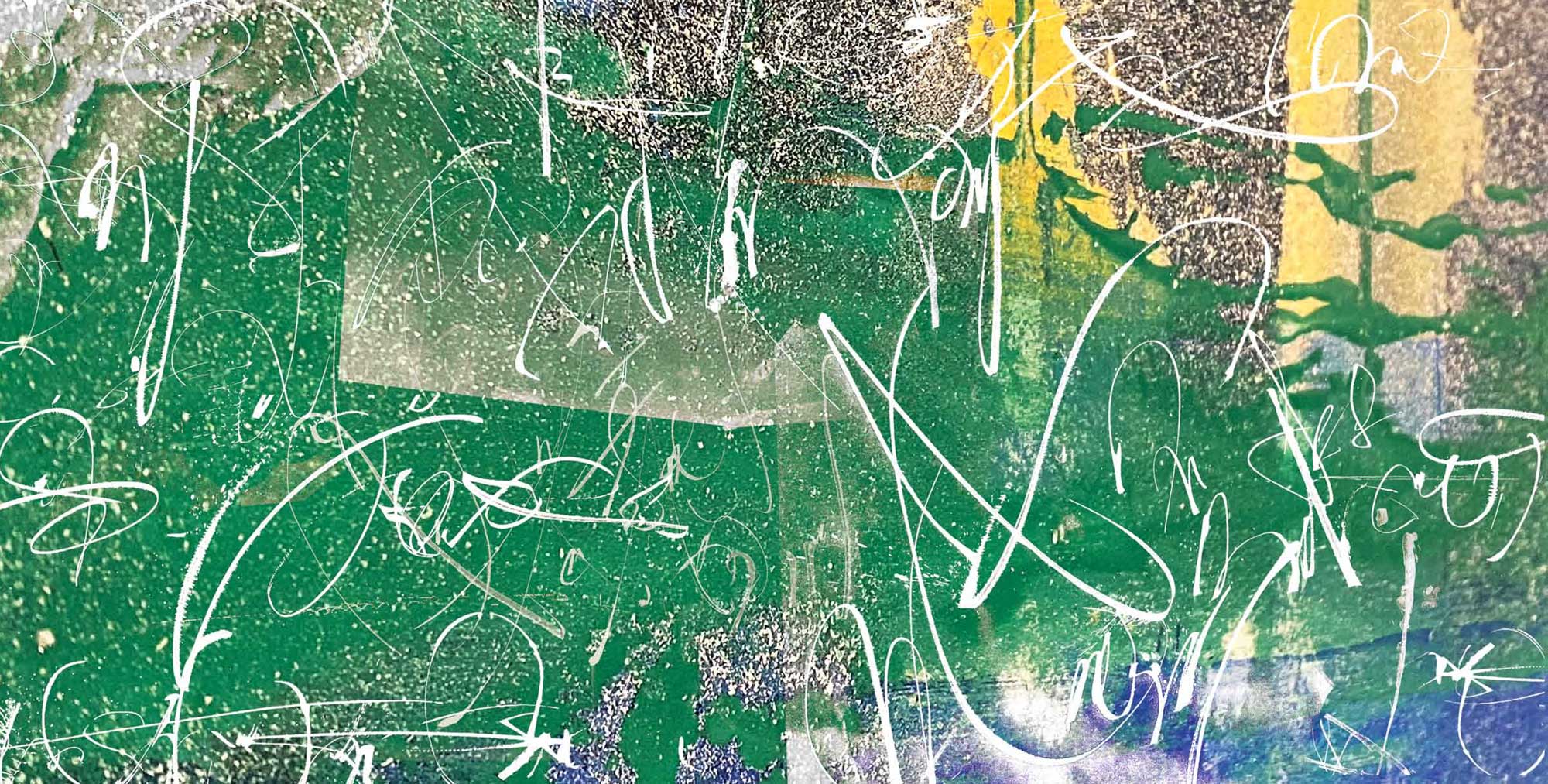

The final phase of the vinyl creation was designing the visuals. We selected a primary image—a zoomed-in macro image of Mako’s painting Golden Sea – Tidal Gestures—but needed a designer who could integrate it with the structure and content of a vinyl cover. Altering Mako’s art was a delicate task, and only one designer came to mind: David Chang.

David took months to meditate on the music and explore Mako’s image. To make markings on top of Mako’s digital painting felt intimidating to David, but Mako unleashed him by offering a gift of courage. “I trust you,” he said. Slowly yet boldly, David stroked gestures atop the anchor image. A multicultural, multi-artist, multi-medium expression of sound and silence.

Lotuses and Mimicry is now a tangible expression of how the tangle of art and friendship can create new beauty in the midst of what has come before. When it finally came back from the vinyl presser in October 2021, it had been over a decade since I first met Mako at Jammin Java and almost four years since the first song had been written. In the age of Instagram, this project was like a picture taken on film and set in a box for years before the maker slowly revealed the beauty in a darkroom. The stories told, words written, melodies sung, and lives lived found their voice, their expression made rich through the slow and holistic journey of creative pursuit with friends.

Lotuses and Mimicry album artwork

Listening for the Lessons

From John Lennon and Paul McCartney to Johnny Cash and June Carter, friendships have unleashed art throughout history. After recounting this creation story, I’ve come to hear a few key lessons, ripples that shaped its eventual dance and may encourage other artists along their way.

First, while it can feel like we are creating ex nihilo, I would posit that artists always create from and with others. Though Lotuses feels completely authentic to my voice, I could never have made it alone. It needed generous layers of different kinds of artists co-creating with and for one another. My songs overlay Mako’s poetry and concepts. Daniel’s production overlays my songs. David’s design overlays Mako’s art and Daniel’s production. Each layer interacts such that they begin to lose their solitary identity; it becomes harder to know where the borders of one end and another begins. Gradually these layers merge into a cohesive creation that is larger than the component parts.

Each layer interacts such that they begin to lose their solitary identity; it becomes harder to know where the borders of one end and another begins.

In our “me” culture, Lotuses is a “we” record. And it’s a “we” that is cross-disciplinary and cross-cultural. Merging music, painting, design, production printing, and prose, the hard-copy vinyl leaves the box of industry behind for the spaciousness of presence. Mako’s Japanese ancestry can be heard in the tones Daniel chose; David’s Korean style can be seen in the marks he made; and my bridge-builder approach to music and life as an American woman who spent part of my childhood in Russia can be heard in the threads pulled to form the final creation. In an age of racial and cultural reckoning, Lotuses shows the way art can hold the complexity of different cultures and lives together.

Second, Mako’s ability to bring artists together for a collaborative experience might seem effortless, but it is a precious habit he has formed over decades. The courage to call others into making with him led him to start the International Arts Movement, write Culture Care and Art + Faith, and establish the Fujimura Fellows at Fuller Seminary. Day to day, he shows that the courage to make is often synonymous with the courage to collaborate, both of which are much easier when refined from task to habit. Now based in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, I am practicing my courage to ask people to collaborate. I recently invited an African American spoken-word artist to join me in my song “Soul of the Nation,” and our performance piece won first place in an international art competition. One of the judges said it was the collaborative voice that made the piece so distinctive and powerful.

The courage to make is often synonymous with the courage to collaborate.

Third, in today’s Google default, it is natural to think the best place to find collaborators is via internet searches and social media feeds. But what if our first question is, Who would I enjoy making this with? Though David and Daniel both have commercial success—David creating for Darren Aronofsky and Daniel for Sufjan Stevens—I wasn’t sufficiently familiar with them to pick them as collaborators. It was Mako’s friendship with both that threaded the needle. And long-time friends were the ones who pointed me toward the Washington Institute performance and the New York City non-profit job. As we begin our creative endeavours, what if we share our vision with a few friends and ask them who would resonate with the spirit of a project? And what if we see the friendships that emerge in the process of co-creation as one of the most beautiful forms of art?

I find myself asking other questions. Mako was both a creator and a commissioner with Lotuses. But am I looking for opportunities to do the same? Each person brought their distinctive gifts to the process. How can I give my gifts in a way that helps another artist find their voice?

Last, I’ll linger on one final note: friendships that lead to the creation of art require not just creating but sustaining as well. If Waterfall Mansion had been a one-and-done event, Lotuses would have never been birthed. But everyone involved has stayed in touch and continues to dream together. On the twentieth anniversary of 9/11 in New York City, I jumped at the opportunity to join Mako and David for an Academy Kintsugi teacher training. Just blocks north of ground zero, Mako and his wife Haejin led David, me, and twenty other participants through the deep work of learning to mend broken vessels with gold. Drawing from the ancient Japanese form of repair, it wasn’t music or notes or vinyl, but we were making together. I now see that our shared record is a musical expression of kintsugi. Notes and images pieced together to bring healing and hope to listeners—and their friends.