W

We call it the “Field Museum” in “Chicago” in a part of the continent named the “United States,” but its contents render such nomenclature moot. Where were those “states” when, 430 million years ago, a tropical Silurian sea—remnants of which are in the museum itself—ennobled this same terrain with wreaths of coral? Where was “Chicago” when, 300 million years ago, the turf that now supports skyscrapers was a swamp that straddled this planet’s equator? Where was what we call “America” when, fifteen thousand years back, ice age mammoths—the scaffolding of their hulking bodies now on tame display—commandeered the margins of the Laurentide ice sheet? Then even America’s native name, “Turtle Island,” was unspoken and unthought. And where was this museum’s namesake, department store magnate Marshall Field, when the short-faced bear—whose reconstructed bones entertain museum-goers today—instilled eleven feet of pure terror into paleolithic hearts? Still, we’re stuck with modern titles, so I found myself entering architect Daniel Burnham’s splendidly neoclassical edifice that we call Chicago’s Field Museum nonetheless.

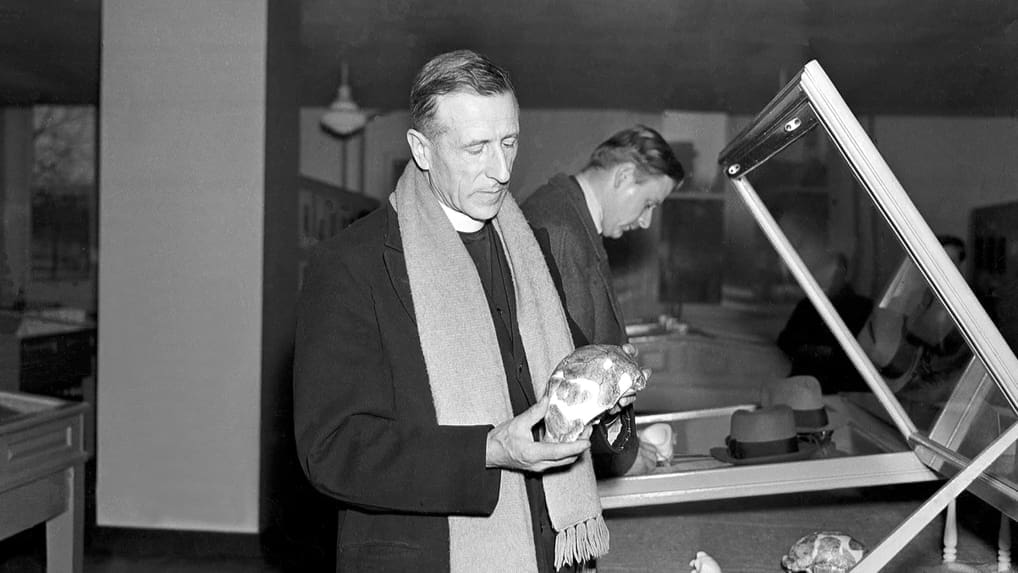

My aim was a return visit to the spectacular Evolving Planet exhibition, and that’s when I saw him, inspecting the teeth of a megalodon jaw. He was reconciled with his tall stature; his crisply fitting overcoat was casually unbuttoned, and his hat was held gently in his hands. He beckoned me and casually asked if I had a light for his cigarette. As I explained that this was not permitted, I noticed he looked familiar. Then he remarked with a mild French accent, “I was allowed to smoke ze last time I was here.”

I followed him as he ambled to the nearby balcony that overlooked brontosaurus bones, totem poles, and taxidermized elephants, where he continued speaking.

“The anthropologist Henry Field invited me, the nephew of Marshall, whose donation built this museum.” He then looked at me with a mischievous smile. “After I helped discover Peking Man, I had more invitations than I knew what to do with.”

It then became clear to me that it had happened again. After Dionysius the Areopagite appeared to me in New York to visit the Met, word must have gotten back to the communion of saints that I was a competent terrestrial guide; or perhaps they were sent to guide me. It was for this reason that Father Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955), the famed Jesuit paleontologist, visited me at a different museum today. This time, thankfully, my bafflement was soon overcome and caused no delay, so our conversation could commence immediately.

I could not help but begin with gratitude. “To defend the Ancient of Days, I once thought I had to believe the earth was young. My discovery of your work changed that, Father Teilhard.”

“Reports like this meet me frequently,” he replied with another smile. “And if you insist on calling me Father, please, make it Père.”

“Can you give me a sense of how my ideas have been received recently?” Père Teilhard asked me. “We can see much on the other side, but not everything.”

“Well, you’re hailed as a prophet or dismissed as a fraud,” I answered, “with not much in between. Upon your death, your many books and essays, suppressed in your lifetime, burst from the press in a variety of (often embarrassingly cloying) editions. I think that may have been part of the problem. Your ideas, which developed throughout your lifetime, hit everyone at once.”

“That is unfortunately true,” he replied. “But science advances quickly. You’re telling me my books are still actually read?”

“Oh, you’re anything but forgotten,” I answered. “You’ve inspired films, symphonies, architecture, sculptures, and even graphic novels. (I can explain what those are some other time.) Just this year, a documentary did a beautiful job of telling the story of your life. It was produced by the Teilhard Project, which nicely collates much of the secondary literature about you on a network you would call an expression of the ‘noosphere’ but that we call the internet. It also certainly helps that your greatest scientific book, The Human Phenomenon, has been more accurately translated into my native tongue at last.”

“Those who read my popular essays and don’t work to engage that book,” he replied, “cannot claim to understand me at all.”

“Did my critics also bear stretchers in the trenches of the Great War?” he asked gravely.

“Even so,” I replied, “among your Christian critics, there are those who say the system laid out within that book is far too tidy. A Dominican scientist named Raymond Nogar said, ‘[Teilhard’s] is the God of the neat; mine is the God of the messy.”

“That’s a good line,” he replied smiling. “Nogar’s Wisdom of Evolution should be better known than it is. He obtained the Vatican’s nihil obstat and imprimatur that always eluded me. Do people still have reservations about my theology?” he cautiously asked.

“Many find your neologisms off-putting,” I replied. “Like calling God ‘the Omega point.’” Sensing he could take a joke, I added, “It sounds like the name of a cocktail bar or an overpriced gym.”

“How is it a neologism if ‘Omega’ is plainly one of the names of Christ in the biblical text?”

“Okay, but there are those who say you don’t take sin or suffering seriously enough,” I answered.

“Did my critics also bear stretchers in the trenches of the Great War?” he asked gravely. “I could have been a captain, but to carry the wounded and dead is the vocation I chose. I assure you, I saw the worst.” He grew silent for a moment. Then he added, “The cross remained at the centre of my vision to the end, as the epilogue to The Human Phenomenon attests.”

“Even so, I’m sure you now realize that your censors were not idiots,” I told him.

“No, they were not,” he soberly agreed.

“Nor was their slowness in evaluating your ideas buffoonish,” I added. “Some have noted your passing remarks about eugenics and tinges of racial superiority. When reading the passionate defences against these attacks by your fierce admirers, I often wish for a frank admission that you got some things wrong.”

“I did, and I know better now,” Père Teilhard said.

Feeling emboldened by his concessions, I continued. “Then there’s your downright naive embrace of technology. You seem to have lacked imagination for how it could go wrong.”

“I did,” he admitted, eyeing a teenager nearby who was glued to her phone. “Has there been a corrective to this?” he inquired.

“Among your interpreters, Thomas Berry helpfully critiqued your techno-optimism with some necessary realism about our ecological free fall. But he also preserved your best ideas. His work led to its own film, popularizing the notion about a universe that always anticipated life and that is finely calibrated to support it. I think you’d like how Berry saw trinitarian relations—differentiation, interiority, and universal bonding—reflected in all of creation. But why he preferred the Gaia hypothesis over more biblical options befuddles me.”

“I think my so-called technological optimism has been overemphasized,” replied Père Teilhard. “As I put it in one of my prayers, ‘The world can never be definitively united to you, Lord, save by a sort of reversal, a turning about, an excentration, which must involve the temporary collapse not merely of all individual achievements but even of everything that looks like an advance for humanity.’”

It was clear to me as he spoke that he was not just citing his own prayers but praying.

He then asked me, “Can you enlighten me a bit more on how recent discussions about science and evolution have progressed?”

“Of course. Atheistic neo-Darwinians and young-earth creationists remain locked in mortal combat,” I replied.

“They deserve each other,” he said, but not without affection.

“Your best insight,” I continued, “that evolution never graduates from personhood, has been happily reinforced. Michael Polanyi confirmed your approach when he argued in 1968 that ‘evolution may be seen as a progressive intensification of the higher principles of life.’ I think you’d also be intrigued with the work of Sarah Coakley. Teaming up with Harvard evolutionary biologist Martin Nowak, she showed how Christian notions of ‘sacrifice,’ ‘punishment,’ even ‘forgiveness’ and ‘reconciliation’ enable us to see what is actually going on in the evolutionary process. Another Harvard biologist, E.O. Wilson, suggested that religious motivation can help rescue us from ecological disaster. Even so, your work is rarely referenced in high-level discussions like this.”

“Your best insight,” I continued, “that evolution never graduates from personhood, has been happily reinforced.”

“Whether I am referenced or not, these developments are particularly exciting,” Père Teilhard replied.

“But I’m sorry to tell you,” I added, “that these developments may be overshadowed by your popularizers. They claim to represent you when they say ‘there is no supernatural God’ beyond the physical world, or that ‘God is incomplete and desires to become complete in you and me.’ It is almost as if their aim is to confirm the worst suspicions of your accusers.”

With this Père Teilhard grew agitated. “How could that possibly be construed as my own view? I repeatedly emphasized that ‘Omega must be independent of the collapse of the powers with which evolution is woven.’ I clearly insisted that ‘we need to do more than say that [Omega] emerges from the rise of consciousness: we must add that it has simultaneously already emerged. . . . If by its very nature [Omega] did not escape from the time and space it gathers together, it would not be Omega.’”

“I think they missed that part,” I said. “Some of your fans also play up your perennialism, making much of your supposed enthusiasm for Eastern religions.”

“The most robust of which is Christianity,” he injected. “I insisted that ‘Christianity, and only Christianity, is both more vigorous in itself and more necessary to the world than ever before.’ I said that ‘unless [Christianity] is understood as the most realistic and cosmic of faiths and hopes, nothing has been understood of its “mysteries.”’ Did my popularizers also miss that part?”

“I guess they did,” I answered. “But some do better. One Franciscan priest, Father Richard Rohr, borrowed a title from your work when he called one of his books The Universal Christ. He argues that ‘the evolutionists rightly want to say the universe is unfolding, while believers can rightly insist on the personal meaning of that unfolding.’ In general, Rohr uses you to teach people to see Christ in all things.”

“And I would applaud him for that,” answered Père Teilhard. “But does this priest extol this ‘Universal Christ’ at the expense of an actual Christmas and Easter, a real nativity and an actual resurrection?”

“Fortunately he affirms both in the book quite clearly,” I answered. “Rohr’s primary complaint is that ‘we Christians have been worshipping Jesus’ journey instead of doing his journey.’”

“But that is a false dichotomy,” Père Teilhard said, shaking his head. “As I wrote the year of my death, ‘I am more and more dedicated to my vocation of devoting my life (what remains of my life) to the discovery and the service of the Universal Christ—and that in absolute fidelity to the Church.’ Hence, going to church to participate in the public worship of Christ is an integral part of the Christian journey.”

“I hope Rohr would agree,” I added. “But whether his many followers would remains to be seen.”

I was faithfully celibate and faithful to my order and to the church. I never wore my censure as a badge of honour or to help sell books.

“On the whole, do you think my influence has been positive?” Père Teilhard asked me.

“Well, you’ve been quoted in major encyclicals by the last four popes,” I told him.

“Still, if these misunderstandings continue,” he replied, “that is less of a comfort than one would think, especially if my ideas are used today to flout basic Christian teaching to which I was never opposed. I was faithfully celibate and faithful to my order and to the church. I never wore my censure as a badge of honour or to help sell books. I never intentionally rankled church authorities. It is one thing to push Christianity to widen itself to accommodate science while intensifying one’s fidelity, as I tried to do. It is quite another to use so-called science as an excuse to court infidelity.”

“So do you agree with those who are petitioning the pope to remove the warnings from your writings?” I asked him.

“Only if the warnings are in turn placed on those who claim to represent me!” he said, laughing.

With this we entered the Evolving Planet exhibition. We passed through a room describing the formation of the earth and into one with a gorgeous display of trilobite fossils, testifying to the birth of sight. After standing silently before them, Père Teilhard said aloud, “Non est quando non fuerit.” Embarrassed that my Latin was not in top condition, I asked him for the translation.

He kindly knocked me on the head with his knuckles and slowly enunciated the words, “There is not when he was not,” as if he were teaching a fifth-grader. He then added, “There is nothing in these trilobites that can be understood apart from the Christ who ever was, is, and ever will be.” He breathed a sigh of exasperation and added, “That is all that I was trying to say.”

“There is nothing in these trilobites that can be understood apart from the Christ who ever was, is, and ever will be.”

“As I remember putting it in Hymn of the Universe,” Père Teilhard continued, “‘The prodigious expanses of time which preceded the first Christmas were not empty of Christ: they were imbued with the influx of his power. It was the ferment of his conception that stirred up the cosmic masses and directed the initial developments of the biosphere. . . . Let us have done with the stupidity which makes a stumbling-block of the endless eras of expectancy imposed on us by the Messiah.’”

We moved through each of the exhibitions in this way, past Cambrian brachiopods through the emergence of the jaw and the first steps of pioneering tetrapods. We admired the twentieth-century paintings by Charles Knight depicting each of these epochs, which—in the recent overhaul of the exhibition—the Field Museum wisely did not discard.

“I think I overemphasized the distinction between the medieval and the modern,” Père Teilhard told me as we walked. “The medieval mystics—Dionysius, Eckhart, Suso, Cusanus—speak endlessly of Christ in and through all things. I wonder now if I wasn’t so much trying to leave them behind as trying to catch up.” He spoke as if he were intimate friends with each of these figures, which I expected now he was.

We passed through another hall of dinosaurs and then entered the “Sue” T-Rex display. As we examined her remarkably preserved skull and teeth, I asked him if he considered the fierce destruction such incisors represented to be wasteful.

“The progress of consciousness toward love is not wasteful,” he answered. “As I put it in one of my prayers, ‘I love you, Lord Jesus, because of the multitude who shelter within you and how, if one clings closely to you, one can hear with all the other beings murmuring, praying, weeping.’ So, yes, I can see Christ in a creature who met its death in these jaws. Do we not worship a Lord who entered the food chain, but at the bottom? ‘Unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you’” (John 6:53).

“That idea is not as far-fetched as you might think in our time,” I answered. “One modern filmmaker made the same point when he imagined a flicker of compassion anticipated even in dinosaurs.”

“I’d like to see that film,” he told me. “As I aged, I only grew more convinced of the place of the cross at the heart of the cosmos. As I wrote near my death, ‘It is exactly the same Cross which I worship: the same Cross, but much more true.’”

We left the dinosaurs, moved through several more extinction events, and found ourselves among the hominoids. We stood before a reconstruction of Lucy, a three-million-year-old hominin discovered in Ethiopia in 1974. Nearby was the reconstruction of a Neanderthal alongside its skeleton. Here I felt I needed to speak up.

“I am not sure I’m willing to abandon the actual Adam, as your work seems to suggest I should. Do you believe in Adam?”

“Believe in him?” Père Teilhard replied. “I’ve met him. Remember, you’re speaking with a man who has already died.”

“So there is a historical Adam?” I asked.

“Not just ‘historical’ in the way that you and I are,” he answered, “but even more so! That was where I went wrong. When, based on evidence from paleontology, I denied the ‘historical’ Adam, it did not occur to me that the event was not measurable by our historical or scientific tools. How oddly foolish, in retrospect, that I thought the lapidary instruments of scientific observation could get past the cherubim with flaming sword.”

“Do you believe in Adam?” “Believe in him?” Père Teilhard replied. “I’ve met him. Remember, you’re speaking with a man who has already died.”

“I’ve heard about this theory,” I replied. “It’s sometimes called the ‘meta-historical fall’ or ‘alterism.’ As Olivier Clément put it, ‘Geology and paleontology, with all their achievements, stop at the gate of paradise, for it is a different state of existence.’ This family of thought has a number of sophisticated Anglican (Peter Green and N.P. Williams), Catholic (Aaron Riches and Paul Griffiths), and especially Orthodox (Nicholas Berdyaev and David Bentley Hart) representatives. Sergius Bulgakov developed the notion beautifully in The Bride of the Lamb. He says our mistake was using ‘a single concept of history for events that refer to different aeons of history.’ The fall ‘belongs to history only as its prologue.’”

“Had such thinking been available to me,” said Père Teilhard, “it might have saved me considerable frustration. And it has ancient pedigree. During my lifetime, I too casually dismissed what I named the ‘Alexandrian type of Cosmogenesis,’ underestimating the depth of the great Christian thinkers of that city and their followers like Maximus the Confessor. I equated the big bang with the beginning of everything but did not consider that it might instead be the manifestation of a primeval catastrophe.”

During my lifetime, I too casually dismissed what I named the ‘Alexandrian type of Cosmogenesis,’ underestimating the depth of the great Christian thinkers of that city.

“But aren’t we supposed to read the early chapters of Genesis allegorically?” I asked him.

“This view does not rule out allegorical interpretations at all,” Père Teilhard answered. “I should have listened more closely to my great friend and chief defender, Henri de Lubac. By recovering medieval exegesis, he fully understood that one need not choose between historical and allegorical interpretations of the inexhaustible biblical text. Hence, the fall is both an actual event and recapitulated in the story of every human life. And so, the fall affects them.”

With this he pointed forcefully to the proto-human remains all around us.

“When the 120,000-year-old Galilee skull was found in my lifetime not far from our Lord’s hometown, the connection thrilled me. But an even better gift is on offer to you in this room,” Père Teilhard told me. He guided me past the proto-humans and placed me before a more recent female burial alongside its reconstruction.

“She was found in my own country of France, not far from the Lascaux cave, that cinematographic display of paleolithic art. She is a Homo sapiens, buried thirteen thousand years ago.”

Thanks to the more recent and more accurate reconstruction, we could see that she would have been beautiful.

“Here is a woman who, like you and me, is certainly fallen—because she died—but she also shares fully in the likeness and image of God. Don’t you love how the museum label innocently calls her a ‘Magdalenian woman’?” Père Teilhard asked me, clearly amused.

“But that’s just because of the region in France she came from,” I objected.

I see in her the Magdalene herself, first witness to the resurrection, and that hope applies to this skeleton as well.

“No, there is more to it than that,” he said. “The name comes from the Magdalene Shelter, a troglodyte village not far from where these remains were found. There is still a small Gothic chapel there dedicated to Mary Magdalene, who, according to tradition, brought the gospel to France. The Field Museum, I suppose, expects me to compartmentalize that fact and view these remains—including her carefully crafted necklace—dispassionately. But I see in her the Magdalene herself, first witness to the resurrection, and that hope applies to this skeleton as well. As St. John says, ‘All who are in the tombs will hear his voice and come out’” (John 5:28–29).

“So you believe in an actual resurrection and the end of the world, not just vague notions of human progress?”

“Of course!” he said, almost shouting. “How could anyone claim my ideas as their own and deny this? As I put it in The Divine Milieu, ‘The divinization of our endeavor . . . pours a priceless soul into all our actions; but it does not cover the hope of resurrection upon their bodies. Yet that hope is what we need if our joy is to be complete.’”

“Still,” I added, “too many scientists still call such hope naive.”

“And I call such scoffing naive,” Père Teilhard retorted. “Their doubts spring from comfortable desk chairs. My faith was forged in the trenches of Verdun.”

We walked on and entered a room of Pleistocene mammals. Giant beavers, mastodons, mammoths, and the short-faced bear surrounded us, along with a massive primeval deer—the Megaloceros—whose antlers were larger than any human hunter has seen for thousands of years. “St. Eustace saw Christ entwined in the antlers of a deer,” Père Teilhard told me. “All I have done is try to see him in Pleistocene antlers as well.”

“The Pleistocene Christ,” I said aloud in reply, not without reverence.

“‘God truly waits for us in things,’” Père Teilhard replied.

His next words were addressed not to me but to the God who was as present in that hall of ice age mammals as at church: “Let your universal Presence,” prayed my companion, “spring forth in a blaze that is at once Diaphony and Fire, O ever-greater Christ!” He was nearly singing the words.

Embarrassed at his indiscretion, I looked around to see if anyone had overheard us. But when I turned to resume our conversation, Père Teilhard was gone.