T

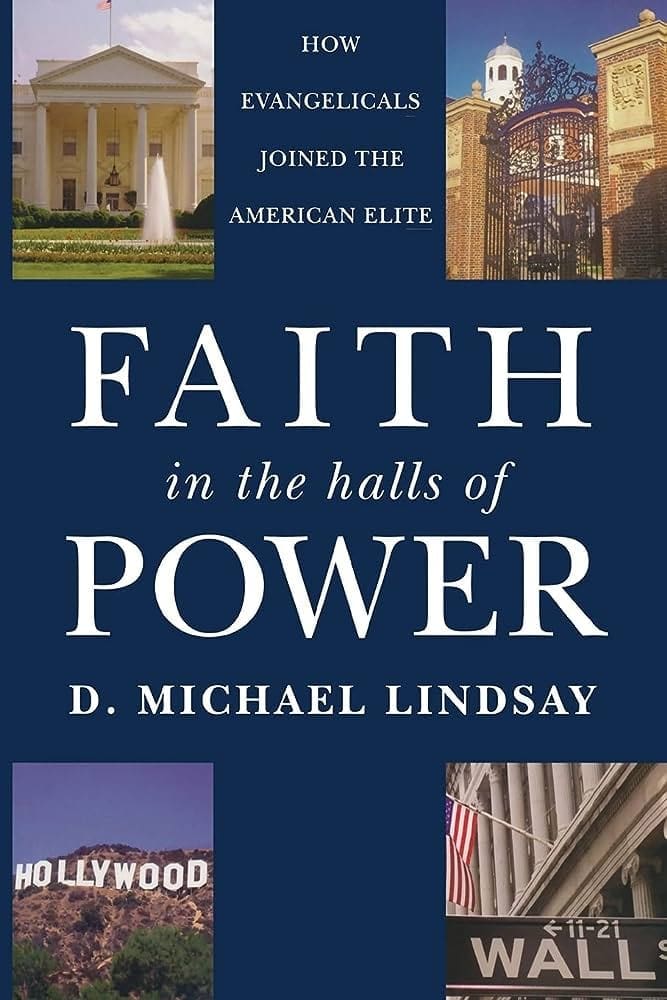

The Rice University sociologist Michael Lindsay has written a compelling analysis of the rise of evangelicals in strategic spheres of national influence. He argues that their growing significance is not because of their numerical growth (a fairly stable 40% of the U.S. population), but rather because of their change in social location. Men and women who identify themselves as evangelicals now hold senior positions in politics, the academy, media, entertainment, and business. Once isolated in suburban enclaves and Midwestern cities, evangelicals are now penetrating urban centres of cultural influence: “How have evangelicals—long lodged in their own subculture and shunned by the mainstream—achieved significant power in such a short time?” This book tells the story of this transformation.

Lindsay defines an “evangelical” as someone who believes: “(1) that the Bible is the supreme authority for religious belief and practice, (2) that he or she has a personal relationship with Jesus Christ, and (3) that one should take a transforming, activist approach to faith.” Evangelicals are those who engage culture rather than separate from it. As evangelicals recognize the priority of culture over politics, this book offers a cautionary tale.

Importance of elites and social capital

Over the past twenty years, evangelicals have created a number of institutions that have fostered networks among the power elite. Among those whose influence is noted in this book are the Fellowship (organizers of America’s National Prayer Breakfast), the L’Abri Fellowship, The Trinity Forum, the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia, the Leadership Network, Act One, and Walden Media. While not all of these organizations and companies are explicitly evangelical, they have been important in fostering evangelical legitimacy within their respective spheres. The end result is that evangelicals have leveraged their economic capital to increase their social capital. “In elite circles,” Lindsay writes, “social networks are critical to prestige.”

This strategy stems from a general acceptance that cultural change is top-down and guided by strategically placed gatekeepers. Infiltrating these gatekeeper networks has been one of the overarching objectives of these institutions. This view, based on research by Peter Berger, Philip Rieff, and Randall Collins, has been popularized in evangelical circles by sociologist James Davison Hunter: “Hunter argues that culture only changes when individuals and ideas infiltrate elite networks and the organizations they control.” Latent evangelical populism has resisted this overt elitism. Charles Colson writes, “I don’t believe societies are moved as much by the social elites as they are by changes in the habits of the heart. I think you have to give people, the mass of people, a different vision to live by . . . John Naisbitt said that fads start from the top down, movements from the bottom up.”

And yet, the reality-defining institutions of the academy, art, media, and entertainment, which are controlled by economic, social, and cultural elites, shape the “habits of the heart” of any given society. Having once worked for John Naisbitt, I can say with confidence that he was speaking about consumer trends, not cultural dynamics. The achievement of these institutions is to be applauded.

Importance of discernment and cultural capital

Lindsay’s story is one of social location. But he does not explore in depth the discernment or cultural capital needed by these evangelical leaders who have now entered the power elite. It is here where a shadow darkens his glowing appraisal.

How and where are these leaders being equipped to use their increasing spheres of influence in ways that discern the cultural idolatries and further the kingdom of God? Where are they encouraged to think biblically about the limits of free market, consumer capitalism, egalitarian democratic populism, and pragmatic technological rationalism? Where are they taught that the tools of modernity are always a mixed blessing and thus must be used with caution? Lindsay notes, “Post-secondary education at a major university is virtually required for upward mobility and access to influential positions.” Where will evangelicals develop an equal theological depth and cultural understanding equal to their leadership positions?

What we find is that these emerging “cosmopolitan evangelicals” came to faith late in their lives and generally acquired their cultural capital outside evangelical institutions. They achieved their positions of influence in spite of institutional evangelicalism, not because of it. In fact, institutional evangelicalism Lindsay identifies with populist evangelicals whose aims are rarely larger than protecting their own turf.

Moreover, these emerging cosmopolitan evangelical leaders show little commitment to the institutional church, preferring, instead, parachurch organizations. Their priority is less on conversion and more on legitimating their own social standing. Lindsay writes, “The leaders I interviewed still want to see their secular peers embrace Christianity, but they tend to see legitimacy as a worthy and more attainable goal. Indeed, for just about everyone I spoke to, legitimacy was a principal concern.”

This would not be such a problem except that they are so disconnected from the local church: “To the extent that cosmopolitan leaders are active in a local church, it is almost always a megachurch, not a small congregation in their community. The declining importance of small, community-oriented churches for these leaders underscores the divide within American evangelicalism.” Parachurch board participation allows them to operate within a business paradigm in which they are already socialized. Megachurch membership only serves to spiritually reinforce their market bias without requiring a great deal of personal accountability. Of late, the megachurch way of “doing church” is coming under increasing scrutiny. Many megachurch pastors are acknowledging that their approach is not changing lives, but is only serving to reinforce cultural patterns.

Lindsay applauds these evangelical gatekeepers’ “elastic orthodoxy.” Although he did not find “evidence of eroding evangelical faith,” he does not explore whether or not these leaders orient their public lives to a biblical worldview and the kingdom of God serves as the animating story of their professional callings. When only 9% of evangelicals have any knowledge of a biblical worldview and spirituality is increasingly relegated to one’s private life, being “born again” clearly does not cut very deep in maintaining distinct convictions or faithful practices in spheres of public influence.

The church’s problem is not that we do not have people where they should be, but that they are not who they should be right where they are. To what extent are these leaders equipped with a theological framework that includes cultural discernment, empowered by the resources of the kingdom of heaven, and “embodied” by those disciplines that transform who they are, right where they are?

The sociologist Alan Wolfe looks at these leaders and sees a ” ‘toothless evangelicalism’: the triumph of market forces and American individualism over doctrine and values.” American evangelicalism has met culture, and culture won.

Many of these new evangelical leaders have convening power—the ability to gather likeminded elites—but few have actual decision-making power within their spheres of influence. It will take more than invigorated social networks if evangelicals are to make a lasting difference for the common good. Faithful stewardship of the cultural mandate demands thoughtful discipleship. It requires leaders marked by theological depth, cultural discernment, spiritual vitality, and church membership. Progress has been made, but there is still much more to be done.