I

God cannot be a thing, an existent among others. It is not possible that God and the universe should add up to make two.

—Herbert McCabe, God Matters

There is only God, who is sacred nothingness to the dualistic mind. Out of this revelation of God comes everything.

—David Frenette, The Path of Centering Prayer

One God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all.

—Ephesians 4:6

It is just after first light on Crooked Lake in the Boundary Waters of northern Minnesota, and a wild swan is restlessly honking. Her feathered white frame and curved neck may be elegant, but the tedious, almost pathetic sound she makes, like the screech of a broken trombone, is not. Two nearby loons, just feet from our canoe, who enhance these lake lands with their signature cry, dive into the water as if to avoid any association with the cantankerous swan. The bald eagles we saw yesterday also keep their distance. Even the squawking ravens, garrulously protective of their cliff nest, descend into a compensatory silence. A beaver nibbling on the shoreline, annoyed by the noise, dips back into the water. But the swan keeps honking, flying in furtive spurts toward the echo that the canyons of Crooked Lake keep sending back her way. My canoe companions and I—there are three of us—are on the water in hopes of seeing a moose. We pity the poor swan, who seems to think that the echo is a mate, though no other swan is in sight.

The swan’s dilemma is ours as well. Eighteen of us, now split into two groups, have paddled and portaged into the Boundary Waters between Canada and the United States to undergo the Ignatian exercises. The fact that the Jesuits were among the first Christian missionaries to explore these lands, and that the same lands’ Indigenous residents have their own version of the Ignatian exercises, makes this form of prayer particularly appropriate. Back in the nineties, when I took a similar wilderness course, we were dropped off foodless for a three-day solo with nothing but a tarp and a Bible and told to fend for ourselves. While I benefited from this strategy, Ignatius offers the kind of instruction I wish I had then, and thanks to an adaptation of the exercises created by my friend Valerie McIntyre especially suited to Protestants, Ignatius offers an ideal framework for college students in solitary prayer.

Photo by author.

And without fail, every time I teach this course, the students are like that swan, just as I was when I was an exercitant myself. As we practice imaginative prayer with Gospel texts, or invite the Holy Spirit to respond to our prayers in our journals—daring to write what we think God might be saying to us—we wonder whether what we are receiving is nothing but our own echo bouncing off the canyon walls. “How do I know if this is God or just me, let alone the devil?” students consistently ask. Perhaps what we call “answers” to prayer are only our own conjuring or, worse, delusions. Our extended prayer times may just be agitated spurts of flight toward what are only echoes of our own pathetic outcries. A colleague teaching this wilderness course with me cites Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Nondum,” assuring students that this is no new dilemma and that they are not the first to have such doubts:

God, though to Thee our psalms we raise

No answering voice comes from the skies;

To thee the trembling sinner prays

But no forgiving voice replies.

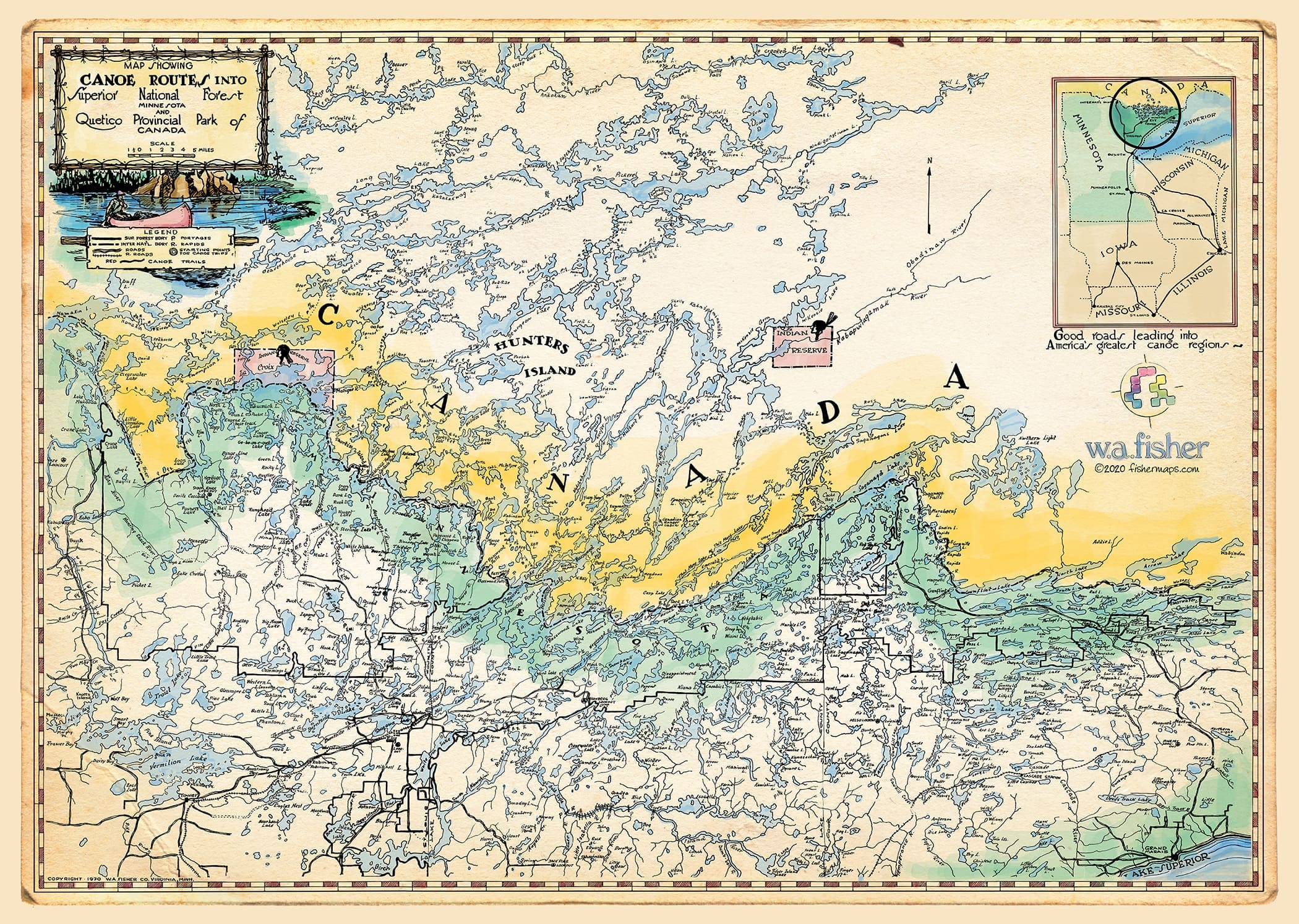

My strategy when faced again with the perennial question of what “happens” in prayer is to use the analogy of Crooked Lake, the very lake we are now on. There is no straightforward answer to the question as to whether the lake is in the United States or Canada; but somewhere in its waters—which are still quite frigid in May—if you just keep paddling, one country gives way to the other. This is why this part of the country, first protected in 1964, and further preserved from logging, mining, and motors in 1978, is called the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. But this serene stretch of pristine lakes, virgin forests, two-billion-year-old rocks, and Native American pictographs is also an apt metaphor for the boundary between us and God.

This serene stretch of pristine lakes, virgin forests, two-billion-year-old rocks, and Native American pictographs is an apt metaphor for the boundary between us and God.

Frank Antoncich Historic Canoe Route Map, copyright W.A. Fisher. Used with permission.

Crooked Lake is part of an old voyageur highway that stretches from Lake Superior to Lake Winnipeg. At one point it thins into the Basswood River, with a spectacular twin waterfall. The portage around the falls is officially in Canada, but no passports are necessary. The 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty states that “all the water communications and all the usual portages along the line from Lake Superior to Lake of the Woods . . . shall be free and open to the use of the citizens and subjects of both countries.” The treaty is still in effect.

The students were thrilled to be in Canada as we took that portage, saddled with double packs or canoes above our heads. I in turn was cheered that I could take my students to another country without having to fill out the additional paperwork my college requires for international trips. I have crossed the Canadian border at official checkpoints dozens of times, nervously clutching my Canadian wife’s green card, hoping there would be no issues. But the boundary of these Boundary Waters, unlike regular checkpoints, is happily indistinct. So it is sometimes, I have tried to explain, with the dizzying cartography of contemplative prayer.

During our prayer times, it slowly becomes apparent that it isn’t always “just me” who responds when I write in my journal what I think God’s answers to my prayers might be. Sometimes it is just an echo, of course, and sometimes it is tormenting interference. Whether this interference arises from actual demons or destructive thought patterns built up over a lifetime is not an entirely helpful question, because whatever answer we choose (and both answers are correct), the perilous effect is still the same. Discerning the actions of the good and bad spirits is the entire point of the Ignatian exercises, and the answer is rarely as straightforward as we wish. But you keep paddling anyway, and sooner or later you are no longer in the country you came from.

You keep paddling anyway, and sooner or later you are no longer in the country you came from.

Photo by author.

On one of our full solo days, a co-leader and I canoed students to select islands on Crooked Lake, a service we dubbed “Canüber.” For Celtic monks, green martyrdom was an exile beyond tribal domains onto distant islands, and this is our temporary version of this ancient Christian practice. They had a rain jacket, some lunch, and their Ignatian packet to work through with the day’s exercises. When I picked one student up at the end of the day, he looked at me with eyes wide enough to betray a recent brush with terror. “I tried to swim to Canada,” he told me. “And I wasn’t sure I was going to make it back.” As I pondered the nightmare we were spared by his survival, I thought he had gotten a rather effective sense of what it is like to encounter God.

Sometimes, however, especially for people closer to my age, the journey toward Canada—our crossing over into the mystery of God—does not feel much like any “experience” at all. That is certainly what “happened” to me during my solo wilderness foray this time around. I sat for what must have been hours looking at an island on Crooked Lake. Whether it was in Canada or the United States I don’t know, and don’t care to know. Over time, I came to see that this island participated in the mystery of God. “As long as a thing has being,” writes Thomas Aquinas, “God must be present to it.” C.S. Lewis insists the Christian cosmos is “drenched with Deity.” But up there in the Boundary Waters, this was as much a matter of consciousness as it was a theological assertion. “Not the abstract truth that God is present in all things,” as Bernard McGinn once put it, “but the reality of what it means to live in this awareness.”

Photo by author.

Here is another way of phrasing it: slowly the God who is behind this island disclosed himself in and as the island, without being in any way limited to the island. A light rain began to fall, light enough that each drop into Crooked Lake emitted perceivable concentric circles that fused into one another in a kaleidoscope of Venn diagrams, as if to illustrate the fact that God and reality mysteriously overlap. When describing union with God in the seventh chapter of the Interior Castle, Teresa of Ávila writes, “It is like rain falling into a river or pool; there is nothing but water.” Or as the Dutch mystic Jan van Ruusbroek puts it, adapting Psalm 42:7, “The abyss of God calls to the abyss” in us.

This Christian paradox of divine presence is to lazy pantheism what freshly ground pour-over coffee is to the Folgers crystals we have to satisfy ourselves with at our campsite. “My only ‘me’ is God. In my soul I see no one but God,” says Catherine of Genoa. “God is who we are more than we are,” writes Thomas Keating. Henri Nouwen testifies that true prayer of the heart is where “there are no divisions or distinctions and where we are totally one.” But in the richness of Christian tradition, these claims exist alongside Gregory of Nyssa’s insistence that “God dwells in you, penetrates you, yet is not confined in you.” R.S. Thomas’s declaration in “Emerging” that “[prayer] is the annihilation of difference” runs parallel to Karl Rahner’s claim that “God establishes and is the difference of the world from himself, and for this reason he establishes the closest possible unity precisely in the differentiation.” Recent studies show that similar themes of mystical unity pervade Luther’s thought as well.

Martin Laird calls this threatening territory not heretical but “treacherously orthodox,” and indeed it may come as a disappointment to those assuming that mystical experience sets them free from doctrine. “The ‘who’ of who we are remains,” Laird insists. “Indeed, all creation maintains its own spectacular particularity. . . . The more we see through the illusion of separation from God, the more fully created we are.” As the pagan Cretan poet Epimenides of Knossos puts it, “In him we live and move and have our being,” an insight elevated to the level of Holy Scripture in the book of Acts.

Photo by Daniel Haase.

Perhaps an equally effective analogy for all this is the mirror. For the Boundary Waters wilderness is an interminable series of mirrors. Unless the waters are stirred, the lake mirrors its shifting shorelines with unerring and effortless fidelity. In the same way, all of creation reflects God. This truth is not an ego boost but a humiliation. It means the being of everything, especially ourselves, is on permanent loan. Acknowledging, instead of being terrified by, this fact is the first step to contemplation. When the stirred waters of our psyche finally settle, this mirroring effect can be felt. Meister Eckhart calls it “God’s magic mirror.” He adds that “an image is not itself, neither is it its own: it is solely that thing’s whose reflection it is, and it is due to this alone that it exists at all.” It follows that only God is ultimately real. Human folly is primarily composed of efforts by created reflections to sunder ourselves from That which we reflect. Thomas Traherne, from “Thoughts IV”:

O give me grace to see Thy face, and be

A constant Mirror of Eternity,

Let my pure soul, transformed to a thought

Attend upon Thy Throne, and as it ought,

Spend all its time in feeding on Thy love

And never from Thy sacred presence move.

What is the state of the soul that is content to be such a reflection? Really it is no state at all. But it might be called an embraced emptiness, a nuptial nothingness, a divine darkness, a calming contentment, an honest humility, a great gratitude, or a devout detachment.

Human folly is primarily composed of efforts by created reflections to sunder ourselves from That which we reflect.

It could be described as an owned ordinariness, limitless love, jaded joy, or wounded wholeness. Its fruits can be a giant gentleness, a cool compassion, a free faithfulness, a powerful peace, and the ability to forever forgive. When we mirror God (as only Christ did perfectly), envy morphs into admiration, vainglory into humility, and anger into sadness. We are relaxed, open, alert, but we might not “feel” much of anything at all. “The highest experience of God is no experience,” says Keating. “It just is.” McGinn, deliberately avoiding the language of “experience” that freights mystical discourse, calls it “direct or immediate consciousness or awareness of the presence of God.”

Far from being an individual achievement, this Christian sense of mirroring unity makes no sense apart from other believers. We navigate these Boundary Waters together. Christ’s prayer for unity is a corporate one: “I have given them the glory that you gave me, that they may be one as we are one—I in them and you in me—so that they may be brought to complete unity” (John 17:22–23). Mystical unity therefore includes those who annoy me and those whom I inevitably annoy. It includes my co-leaders, who call me to a deeper level of holiness, who spare me from accommodating the spirit of the age, which—blasphemously inverting the wisdom of Meister Eckhart—considers God to be a reflection of us. But the cross terminated that illusion, and there can be no true Christian mysticism apart from the cross, the imagery of which pervades Traherne’s poem about the mirror.

There can be no true Christian mysticism apart from the cross.

Indeed, I wonder if the Eckhartian mirror tradition is best understood by the great Lutheran thinker Johann Arndt (1555–1621), who prioritizes the perfect mirror of Christ. Only his blood can fully wipe our muddy mirrors clean. Fittingly, another, much larger lake that straddles Canada and the United States, which we may explore next year, is Lac La Croix.

Photo by author.

As our group cooks freshly caught northern pike, and as our conversations around the fire extend so much further than they would in a regular classroom, the case for this way of teaching expands. With fresh calls for wilderness education from many quarters to combat our screen apocalypse, I expect this style of learning to enjoy a new wave of popularity. We don’t have to throw soup at the Mona Lisa to get our students to care about the environment; the beauty here does that work for us. We don’t have to force-feed them critical race theory. In the first portion of our trip, they meet the Ojibwe personally and perceive them to be what they already are: brothers and sisters in Christ. There is no need here to scold students about screentime. Without any prompting they rise early to watch the sunrise in rapt silence, and—several of them confess at the trip’s conclusion—they don’t even really want their phones back.

Several of the students confess at the trip’s conclusion that they don’t even really want their phones back.

The entire Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness feels to us like one massive northern monastery. The permit process even resembles the process of obtaining a permit to visit Mount Athos, except for the fact that here women are allowed. Our days are bookended by paddling at dawn and basking under northern lights, and all of us sense that God is here in a unique way. Still, the same God who mysteriously is these islands, lakes, rocks, and rivers (without being reducible to them) is present in everything else as well, save our own sin. He is the God not only of wild places but of tame places too. If I look at the flame of my prayer candle from the right angle through its melting yellow beeswax, it looks like a Boundary Waters sunrise. Our time in the wild equips us to enter our screen-glutted world with the same contemplative disposition. “Meet everything with a steady, silent gaze,” writes Laird. “What notices the mind game is free of the mind game.”

Photos by Lydia Scott.

We did, by the way, see a moose on that early-morning paddle. Examining the Crooked Lake pictographs that morning, which are hundreds of years old, we beheld an image of an eccentric pipe-smoking moose with a lightning bolt for a dewlap. And later that day we caught up on the whereabouts of that panicked swan. A group of four giggling students in two canoes glided into our campsite in the late afternoon. They sheepishly reported that they had just witnessed two twitterpated swans in exhibitionist union on the open water. The swan’s echo, I then realized, was not a deceptive decoy but merely a side effect, and the pursuit was not in vain.

She had found her mate.

Thank you to my co-leaders Daniel Haase, Lydia Scott, and Lily Lebo, along with Micheal John Reszler, Valerie McIntyre, Hannah Eshenhaur, R.J. Boyle, and the Boundary Waters 2025 students for making this year’s Boundary Waters class such a success.