F

Facing a valley of dry bones, God asks the incredulous Ezekiel, “Can these bones still live?” In our current moment, we might see the desiccated remains of the Church—I use the uppercase to refer to the united body of Christians figured in Scripture (even if divided in temporal expression)—and ask a similar question: Can this Church still speak? Can the fractured body of believers suppressed by the forces of the modern world still bear witness in any authoritative way?

In modern, liberal societies, the Church’s voice has been marginalized, diminished, and even silenced. And not by accident. This is an accomplishment of what some scholars, such as Rémi Brague, refer to as the “modern project,” a project that centres on emancipating humans from all that purports to stand above them. Such a project demands the defanging of the Church, the systematic muting of its authoritative voice.

The social orders of modernity are constructed around such a “free” individual and seek to institutionalize the sovereignty of the human will. This means that religion, and religious bodies such as the Church, must be stripped of any public authority—reduced to an enclosed “private” sphere where their voice is permitted only as it’s siloed. In such a framing, religion becomes an “opinion,” a private practice without public bearing.

According to leading political theorist Pierre Manent, “the original task of liberalism”—which is the political philosophy undergirding modern political orders—was “to establish that religious opinions were of no interest to political authority.” Manent argues that the movement of the Enlightenment as a whole had for its goal the establishment of the liberal, neutral, and agnostic state. This required domesticating the Church, turning it into a strictly private association. “The neutral state,” Manent explains, “must work toward the Church’s complete disestablishment, transforming it into a strictly private association and reducing as much as possible its means of influence.”

This reduction of the Church to a private association, or “voluntary society,” is an expression of the social contract theory foundational to liberal political theory. Social contract theory begins with a theoretical “state of nature” in which society does not yet exist. The basic unit out of which society is constructed is the detached, pre-social individual. Such abstract, autonomous individuals emerge as naked wills, auto-originating and constructing everything around them driven by rational self-interest. Relations—personal or institutional—are non-existent from the outset, and are entered into only voluntarily. This means society and social bodies are determined by an instrumental and consumerist (or market) logic. We “contract” for mutual self-interest, and this is what forms society. Society is merely the sum of the encounters in which these individuals collaborate to maximize their advantages. Any relations and obligations are chosen in the pursuit of the construction of the self or a world for one’s own benefit. Authority is legitimate only if and when it is chosen and represents the will of the people, and thus continually chosen.

In modern liberal societies the Church is not so much a given reality to which one must respond but a buffet of options for the choosing.

Social contract theory shapes both our political and our ecclesial loyalties. It has created a new social imaginary of the Church, one that has catalyzed its fractured state. Denominationalism, Peter Leithart argues, has become the established religion of Western societies. When a church fails to meet felt needs and desires, many are quick to switch to another existing denomination or to construct an entirely new one. In modern liberal societies the Church is not so much a given reality to which one must respond but a buffet of options for the choosing. And as we have seen with the rise of the “nones” and the “great dechurching,” many increasingly choose to opt out entirely. In his important recent studies, social scientist Ryan Burge has revealed that over the past twenty-five years around forty million Americans have stopped attending Church. Even for those who remain in churches, many continue to neglect official teachings, such as the Roman Catholic Church’s position on contraception.

Can this fractured Church, in such a culture, still speak with any authority today? And even more challenging, what exactly is the Church that we should listen to?

Hearing the Muffled Church

The Church’s public voice is undermined due to the liberal state’s domestication efforts and the market logic endemic to modern society. But to make things worse, the Church is divided into a multitude of denominations. And such division makes it very difficult to hear with any clarity. Her voice is muffled. One of the premier ecclesiologists of our day, Ephraim Radner, goes even further. He argues that a divided Church’s ability to hear the Word is tragically disabled. Such a Church has lost the capacity to properly discern, respond to, and declare God’s Word. Thus, the public witness of the Church is crowded out due to the cacophony of denominational division. Denominationalism deafens. How can people hear the message of the Church when so many churches are speaking independent of—and often at odds with—one another?

Denominationalism “institutionalizes division,” according to Leithart, and enshrines choice. This choice crowds out truth. In this respect, denominationalism is a species of liberalism. Liberalism replaces objective goods with subjective values, and sets up a dichotomy between facts and values, which map onto another dichotomy of public versus private. It reduces religion to a matter of private opinion—of values—in contrast to public truth and facts. In such a framing, “church” is a matter of opinion and a matter of choice.

But to convert religion into a mere choice is already to deny its reality. It is, as philosopher D.C. Schindler argues, to absolutize potency over act; to privilege options and possibilities over the given. Liberalism, Schindler posits, means a “neutralizing of the actuality of the given truth,” whose fundamental symbol is the Church, in order to legitimize and provide space for choosing among diverse options. But the Church is a given reality, not a group of individuals who decide to come together with like-minded folks. Christianity, argues Schindler, is a “form”—“a concrete and visible reality in the world.” Thus, the essence of liberalism is the rejection of the Church as the actual presence of Christ in history . This undergirds denominationalism, according to which Christians can choose which “church” to belong to. Unfortunately, coming back to Radner, all choices are now available to the contemporary Christian except the Church catholic .

Another reason the Church is so difficult to hear today is not merely division and denominationalism, but also the implicit consumerist logic that pervades our culture. With the options before us, we are inclined to choose our “church” according to preferences and what we can get out of the particular denominational association. The “church” is then approached as a product to consume, a service provider, or even a brand to enhance one’s public image. What should be the body of truth (1 Timothy 3:15) is reduced to a tribe. If you are no longer satisfied, you can simply switch teams or create a new association.

The essence of liberalism is the rejection of the Church as the actual presence of Christ in history.

Much of this starts with the way we join an ecclesial body in the first place. Think of the predominant metaphor employed today to describe this process: church shopping. Though this term might be used somewhat innocently, it reflects a logic antithetical to a healthy relationship to the Church. It predisposes us to approach the Church as another commodity we consume.

Over the years I have advocated an alternative metaphor to better—though imperfectly, as I will explain below—describe this process. Instead of “shopping” for a church, consider the process as more analogous to dating (at least dating before the commodification of the process in “hookup” culture and the “swipe-right” era of online dating). Why is this more healthy? Because dating is relational and, ideally, ordered to mutual self-giving. Dating is tethered to the goal of marriage. Dating is provisional. It is a discernment process in view of a covenantal commitment. And a covenant differs substantially from a market-logic contract. A contract is entered into voluntarily for mutual self-interest and entails conditions, which, if not met, permit a party to leave without much difficulty. And in such a scenario it makes little sense to remain, since the point of the contract was the conditions for maximizing self-interest.

In a covenant, à la marriage, one cannot (or should not) abandon it easily when the other party fails to live up to one’s expectations or desires. There is a more comprehensive self-gift involved, and so there should be more constraint involved. In fact, joining a church in some denominations—like the Presbyterian Church in America, where I am ordained—is described in terms of submission. In the Book of Church Order, after listing vows basic to Christian discipleship, the minister is instructed to ask the candidate, “Do you submit yourselves to the government and discipline of the church, and promise to study its purity and peace?” So, technically, one does not merely join a church but submits to a church, its teaching and its governance.

To be sure, the marriage analogy breaks down in certain respects. While marital imagery is used in ecclesiology, it describes our corporate relationship to Christ—who is the Bridegroom. When we unite with him, we are united to his body (Romans 12; 1 Corinthians 10–12; Ephesians 2:16; 4:4; Colossians 3:15) as bride (Ephesians 5; Revelation 19; 21). These cannot be separated. Thus, this imagery does not exhaustively describe our decision to commit to a particular congregation or denomination.

The Church as Mother

Another image for the Church that avoids voluntaristic meanings—which can more easily map onto marriage—is the image of Church as mother. Our mother is not someone we choose; she is a given reality to which we must respond accordingly. Salvation is described as a new birth (John 3), and though the effective agent is the Spirit of Christ, the instrument to bring us to faith is the witness of other believers who have gone before us (Romans 10). Through faith, we receive God as our Father and fellow Christians as spiritual siblings (Matthew 12:48–50; Mark 3:34–35; 10:29; Luke 18:29; the Lord’s Prayer; references to “brothers” in the epistles; etc.). Theologians throughout history have connected this to the Church’s maternal nature, as the one who is instrumental in bringing us to faith and nurturing us in our new life of faith.

Cyprian famously declared that “no one can have God as Father who does not have the Church as Mother.” Augustine echoes this, and John Calvin picks it up as well. In his early correspondence with Cardinal Sadoleto, defending the Reformation cause, Calvin says, “As we revere her as our mother, so we desire to remain in her bosom.” He emphatically reiterates this logic in book 4 of his Institutes of the Christian Religion, which draws attention to the motherhood of the Church. In the opening lines Calvin explains that the Church is the institution “into whose bosom God is pleased to collect his children.” Therein, Christians—as the adopted children of God—are “guided by her maternal care until they grow up to manhood and, finally, attain to the perfection of the faith.” He explains that the visible Church is the mother of believers, and from this he argues that Christians must receive her nurture their whole lives. “There is no other means of entering into life,” Calvin goes on to say, “unless she conceives us in the womb and give us birth, unless she nourish us at her breasts, and, in short, keep us under her charge and government, until divested of mortal flesh, we become like the angels.”

We are dependent on this mother we have received, and we must follow her guidance and government. We never grow out of our need for her. Henri de Lubac devoted an entire book to this theme titled, appropriately, The Motherhood of the Church. He reiterates that we are given new birth in faith through the instrumentality of the Church. Through her, God saves and renews us and gathers us together into a new shared life. But de Lubac is more emphatic than maybe any other theologian about our perpetual dependence on mother Church. He draws attention to an important difference between natural and spiritual mothers: Christians do not grow more independent of their ecclesial mother, but rather become progressively bound to her. De Lubac expounds that “the maternal action of the Church toward us never ceases, and it is always in her womb that this action is accomplished for us. . . . Her mission of giving birth always remains.”

Combining the Pauline instruction that Christians must become adults in Christ with Christ’s imperative to become like little children, de Lubac argues, “The more the Christian becomes an adult in Christ, as Saint Paul understands this, the more also does the spirit of childhood blossom within him, as Jesus understands it. Or . . . it is in deepening this childlike spirit that the Christian advances to adulthood, penetrating ever deeper, if we can put it this way, into the womb of his mother.” Maturity is thus growing more willing to listen to her guidance, to become more childlike.

To properly understand the Church and how we should listen to her, we must ask: Do you love her? Do you see her as a gift? Do you see her as inextricably bound up with the new life you have in Christ? Do you know that you need her instruction for nourishment and growth? It is only when we recover the perception of the Church as spiritual mother or bride of Christ and not just another consumer choice in our liberal order that we can even begin to conceive of answers to these questions.

Church Discipling

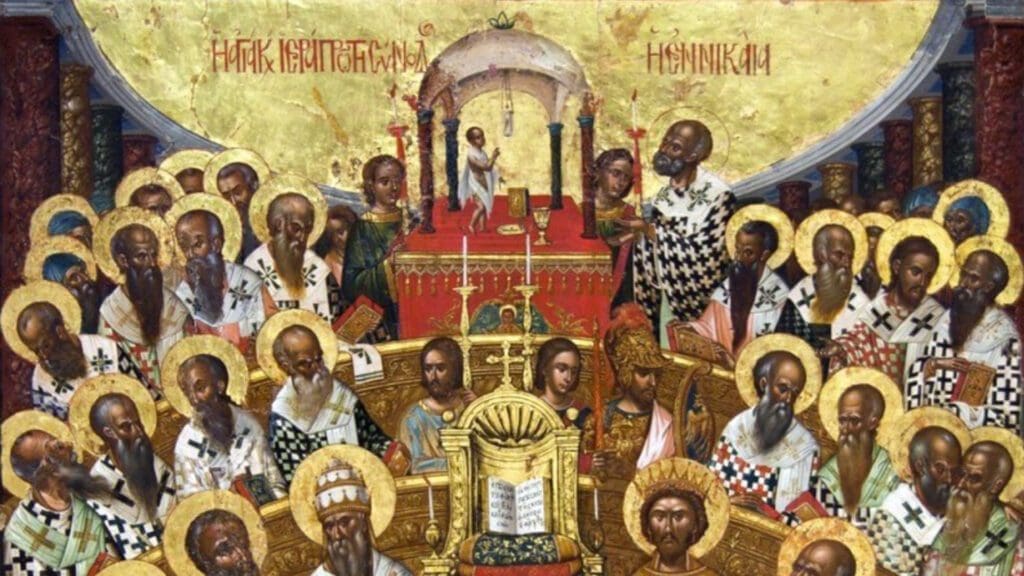

If the Church will nurture us as a mother, we must have shepherds who know us and are accountable for us (Hebrews 13:17). Therefore another basic descriptor for a Christian is “disciple.” And disciples need discipline (Hebrews 12). They need guidance and correction. None of us are able or expected to chart the Christian path on our own. Christians must place themselves under the tutelage of elders in the faith, and official officers of a congregation. But it should not stop there. The congregation should be guided from beyond the congregation. Our churches should be instructed and corrected by the Church—by contemporary congregations and broader assemblies (Acts 15), and by the tradition of the Church, which we have received (1 Corinthians 15; 2 Timothy 3:6). But how is discipline to be performed effectively in a divided Church? In our denominational landscape, a teacher who breaches orthodoxy or a member who is obstinately unrepentant about public, socially disruptive sin can easily join other fellowships or create their own, thus effectively neutralizing discipline.

Since Christians today must still act amid these dilemmas, what should we do to listen as best we can to the Church? This is where Radner is, again, particularly helpful.

In the midst of a divided Church, defined by a multitude of denominational options, Radner urges us to forgo choice. He expounds on the virtue of “staying put.” This isn’t perfect, but no option is. Once we have committed somewhere, or been brought up in a certain ecclesial body, Radner argues that the burden should be placed on leaving, rather than staying. This is a way that we endure in love, and submit to the given:

To be thrown back on past choices . . . is also to be thrust up against the human embodiments of the Church’s life, stripped of their ideological masks—that is, the people of God who make up the body of Christ. When choice is removed, we are faced with demands of life together, in all of its modern burdens. . . . They are what is left when there is no future strategy to hide them behind. And, of course, it is only here, within such a body of egregiously present members, that the true life of the Church as Christ’s own takes flesh, in the demand for and inculcation of the somatic virtues that Jesus shares with us, pictured in something like Romans 12: affection, honor, zeal, service, joy, hope, patience, compassion, constancy, forgiveness, generosity, hospitality, suffering. There are no choices around these things; only the inescapability of the divinely given.

Submission to the given in this way is transformative. It helps us to hear the Church today.

Now, we must admit where this can go wrong. Sometimes staying in place can be deadly, and it would be wise to flee (Matthew 10:23; 12:15; Acts 8:1; 9:25; 14:6; 17:10; 17:14). And submission is not absolute. Consider the commands to submit to husbands (Ephesians 5; 1 Peter 3) or governing authorities (Romans 13; 1 Peter 2). The Bible teaches that such authority must not go against or beyond what Scripture has instituted, and tradition has explained that tyranny annuls claims to authority. However, our default must be to submit, including in our ecclesial commitments. We need the Church, and her guidance.

How Should the Church Speak?

As I have noted, many of the forces of modernity push the Church’s authority to the private sphere; these also relegate the Church to otherworldly, “spiritual” concerns. According to this framing, the Church’s teachings have no public bearing on the world beyond her members. Even with her members she only provides authoritative instruction about a world to come—thus not touching on temporal realities, on life in this world.

The Church must never consider herself a private cult, overseeing a purely inward and personal religion. Her witness pertains to the whole of humanity.

While the Church does not rule over the state or have expertise in every matter, she is concerned with this life and with humanity. She is, as Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI have argued, an “expert in humanity.” Furthermore, as Reformed missiologist Lesslie Newbigin has expounded, the Church bears witness to a public truth, that Christ is lord over all. The Church must never consider herself a private cult, overseeing a purely inward and personal religion. Her witness pertains to the whole of humanity. De Lubac also resisted such privatization. Since all of humanity finds salvation in Christ, there is nothing that can remain alien to the Church and there can be no question of limiting her domain. While her authority is “spiritual,” this is no limitation, since the spiritual is always mixed with the temporal. But this authority must be “in proportion to the spiritual element present.” Therefore, the Church’s authority pertains to temporal matters, even if she does not rule over temporal authorities.

This first of all begins within the household of faith.

While the Church should resist laying down new laws and binding consciences about the nitty-gritty affairs of temporal life that go beyond its competency and authorization, she can and should provide guidance to help her members faithfully apply Scripture in the fullness of life. As an “expert in humanity,” the Church understands humanity’s depths and destiny, and has been entrusted with the interpretation of the Word, which illuminates nature and our life in the world.

Consider how this dynamic plays out regarding the family. It is not the case that ministers should intervene in all things in family life, but the family governs itself as it takes its bearings from Church teaching. And consider how this can ripple out into broader society. The presence of Christian marriages conforming to God’s Word and guided by Church teaching reveal to the world what marriage is supposed to be, and in many cases societal practices are progressively transformed.

Broader society can thus learn from the Church through the witness of her members as they embrace the Church’s teachings in their lives. Alongside this, the Church also has duties to speak boldly about issues in broader society and to political leaders.

This is clearest in a situation that demands public resistance, sometimes referred to as a status confessionis. Such a situation was evident during World War II, when the confessing church issued the Barmen Declaration after the Nazis had increasingly revealed their wicked policies and had begun to impose their ideology on the churches in Germany. Even the Westminster Confession of Faith includes a provision for such “extraordinary” circumstances, in which official ecclesial bodies are permitted (maybe implored) to issue public statements in opposition to civil authorities. However, these cases are by nature rare, and this form of communication should be pursued with caution. If the Church is to retain its unique witness, it must resist the temptation to respond with public statements and “position papers” on every issue deemed newsworthy by the world.

But the Church also has a more regular role with regard to civil leaders. To perform their tasks, political authorities need to learn from the Word, whose public interpretation is entrusted to the Church. Abraham Kuyper’s most prominent critic among his contemporaries, P.J. Hoedemaker, sought to retrieve this classic Reformed point. The state is accountable to the Word, which the Church interprets; the state is enlightened by the Church to fulfill its duties. “The civil government,” argued Hoedemaker, “ought to accept the truth which the Church confesses and the light which it kindles for the proper understanding of the Word, to the degree necessary to fulfill its vocation.” The magistrate must be enlightened by the public interpretation of the Word by the Church. It must recognize the Church as a divine institution that bears witness to truth.

But this leads us once again to the major dilemma of a divided Church. To whom should the state listen? Hoedemaker acknowledged that division and denominationalism neutralize the Church’s witness to the civil rulers. Thus, he promoted a version of conciliarism in which various ecclesial bodies that bear the marks of the true Church unite in some form to enable the prophetic witness of the Church to the nation and civil rulers. Along similar lines, Leithart proposes what he calls “micro-Christendoms” each led by a “metropolitan church.” This body would be composed of a council of local pastors from Nicene churches. In united witness, the Church would speak to their cities and civil leaders.

Can the Church still speak? Perhaps the better question in our modern world is: Even if it did, would we listen?

It is hard to hear the muffled voice of a divided Church that has been imagined into the margins of opinion and otherworldly concerns. But Christians should reconsider the Church as the given bride of Christ who is also the mother of believers. And we should position ourselves first and foremost to listen to that Church wherever we are. And we should continually pray that ecclesiastical leaders will continue to find ways to make the Church’s voice more audible to the world and that the Spirit would go out and give those with ears the ability to hear.