Some of us remember Enid Strict, the infamous and wildly popular “church lady” played by Dana Carvey on Saturday Night Live. Enid was a caricature of the busybody finger-shaking moralist no one would want to share a pew with. Her routines included condemnations of all things sexual, judgments on the rich and famous, and a little “superior dance” she performed to music played by an organist named Pearl. Perhaps I shouldn’t admit to having watched SNL, let alone laughed at the antics of the church lady. But I did. I have also shared Jane Austen’s wry amusement at the Reverend Mr. Collins’s obsequious panderings and laughed out loud at Stella Gibbons’s portrayal of Amos Starkadder, pastor of the Church of the Quivering Brethren in Cold Comfort Farm, who delivers stock hellfire sermons in Scottish brogue. Figures like these continue to amuse readers and viewers by exposing the false pieties and self-serving practices of Christians at their worst.

Caricatures of Christians and their churches go back to Chaucer and beyond, some finding their inspiration in the Gospels themselves, where Jesus not only rebukes the Pharisees but also makes them look ridiculous. We’re an easy target. Churches have never occupied an altogether comfortable place in culture, even where they have borne the state’s imprimatur. North American churches, shaped by settlers who imported their own, sometimes unorthodox versions of ecclesial practices, have been home to outliers, autodidacts, and undisciplined zealots. Frontier congregations found their relationship to Rome, Wittenberg, and Canterbury stretched and thinned by distance and the unceremonious necessities of survival. American churches bear the shame of having sanctioned slavery and even genocide.

Yet churches have survived the potshots of satirists and, more consequential, internal disorders and diseases that have afflicted them for centuries: pride, envy, anger, avarice, gluttony, lust, and sloth—just to review the short list. A lot of them not only survive, but also thrive. Many are repositories of great spiritual wealth hidden behind flaking paint and dated amber windows. They are a last resort for people who have tried bars, bowling leagues, service clubs, and block parties and still find themselves lonely and directionless. They offer surprises to people who come as pallbearers to their mother’s funeral only to find themselves wanting, for reasons they can’t quite name, to return the following week. They preserve language that lifts the mind out of the muddy waters of media-speak and into unnerving encounter with the Word that was in the beginning. Some of them. Not all of them.

By virtue of moving around a good bit, I’ve had occasion over the years to visit churches, choose among them, and change my mind occasionally. What I want and need from church now isn’t at all what I hoped for at fifteen, when I spent Sunday evenings in earnest Bible study with the youth group, or at twenty, when I emerged from years of camp songs into the quiet dignities of liturgical worship, or at thirty, when I found deep respite in the sturdy silence and simple practices of Quakers. There were stretches of time when, afflicted with church fatigue, I didn’t go at all. I was a cradle churchgoer, child of missionary parents, and the very idea of sleeping in, reading the Times in my pyjamas, and heading out for a Sunday morning bike ride was both tempting and unsettling. Ultimately, it was unsatisfying, so I returned, but my stretch of churchless Sundays did give me some understanding of and sympathy for the inertias that keep people away from church.

There are a number of reasons not to go to church. At risk of stating the obvious, here are a few:

Some churches are clubby and exclusionary. They have a house style. Long-time parishioners know all the moves, liturgical and social. They refer to their favourite person of the Trinity in a socially correct way. There appears to be a dress code. They shake hands with visitors at the “coffee hour,” but don’t exhibit much real curiosity about what might have brought them there. The dominant demographic is painfully apparent. Those who don’t fit the profile might consider going elsewhere.

Some churches offer easy, oversimplified preachments that provide scant help to those grappling with the complexities of contemporary life. Sermons tend to reiterate familiar condensations of the gospel message, but only the parts of it that pertain to a rather insular range of concerns, with a heavy emphasis on comfort rather than challenge. The intention seems to be that people leave feeling affirmed, though it also seems likely that some leave feeling hungry, restless, and unsatisfied.

Some churches’ efforts to be relevant lure them into imitating popular culture in language, music, and technology, all rather less effectually than their secular counterparts. Sometimes this involves screens and electric guitars. Sometimes it involves adults attempting awkwardly to sing along with swaying high school vocalists. Sometimes it involves banners and slogans. Some notion of a common denominator appears to determine worship style, but the result is a confused mix of media and a diluted message.

Some churches are boring. Their sermons, websites, and congregational enterprises tend toward the predictable. They play it so safe, seeking not to offend anyone anywhere on the political or theological spectrum, that they become lukewarm. And we know what Jesus does to the lukewarm.

Some churches are partisan. They support candidates and single-issue voting. Rather than nuanced reflection on doctrine they become doctrinaire.

The list is depressing. I edited it down. But here’s the thing: the list of reasons to go to church is longer and more interesting. Compelling, even. It’s a list I’d be glad to share with the cynical, the indifferent, and the uninformed. It’s not an indiscriminate invitation to hasten out next Sunday seeking the nearest steeple, but a challenge to find, even if it takes some church-hopping, those places where the Spirit is working quiet wonders among ordinary people. Here are five reasons, not necessarily in order of importance, I would give the reluctant and the skeptical to check out church, despite their reservations:

A healthy church will help you get over yourself. One of the primary aims of good preaching is to invite us into a story much larger than our own. In a healthy church, conversation about what the privileged owe the poor will be made local and urgent every time the story of the rich young ruler is read. Personal wealth and the wealth of the nation will be re-examined with a critical eye every time the parable of “bigger barns” comes up, or the camel squeezing through the eye of a needle. Shared prayers of thanksgiving will not only reflect but also awaken gratitude. In a healthy church people’s needs are made known and other people organized to help meet those needs—deacons, elders, volunteers who take food to the housebound or take people who can’t drive to doctors’ appointments. In a healthy church you begin to recognize yourself as someone with gifts to give—time, money, energy, expertise—and you begin to want to give them, because the grace that comes with giving is suddenly so startlingly apparent. You find a compassionate curiosity growing in you that leads you into conversation with people you might otherwise have avoided. You take a second look at them as you reach out to exchange with them a peace that sometimes passes understanding.

In an urban church we attended for a time homeless people came regularly to worship. Some were disruptive; one mumbled, one snored, one wandered around the back of the sanctuary. They were familiar folks who weren’t getting nearly the help they needed. One was unwashed, and smelled. Sharing a pew with him was challenging, but when he happened to sit close by the thought never failed to occur to me that next to him is exactly where Jesus would be. By choice.

God loves you with infinite, unconditional love, we learn in church, but to experience that love fully, you have to get over yourself—excessive concern with your own welfare, your own family, your own ambitions or failures. When you enter into the life of a church, you are freed to be a servant. It is true that you can discover the joy of generosity and service elsewhere. But healthy churches are reliable places to find those opportunities, every week at the back of the bulletin or in the newsletter or on the website, to witness the fruits of the Spirit, who brings humble efforts to fruition, and to be reminded by story, song, and your neighbour’s example what Christlike looks like.

A healthy church will allow you to acknowledge guilt and experience forgiveness. As Toni Morrison’s wonderful character Baby Suggs puts it to her congregation, here you can come to “lay it all down.” It may not seem that acknowledging guilt would be a particularly attractive reason to attend church, but you find, if you do it, that it’s amazingly restorative. Most of us carry around guilt like a stone in a pocket. Sometimes you get so used to its weight you stop even noticing it. So it can take a long time, if you’re leading what seems to be a decent and innocuous life, to get to a place where guilt becomes pain and you long for forgiveness.

When you do get there, a healthy church is a good place to go. Of course, the first place to go might be to those you’ve offended, to ask directly for forgiveness or make amends. Jesus endorses that bit of common sense, as does every Twelve-Step program. But if those you have offended have died, or are unavailable, or if your guilt has metastasized into pervasive unease or a troubling awareness of complicity in culture-wide injustice, it requires a different kind of healing—one pastors and priests are trained to help with. In churches one may discover how significantly pastoral care differs from psychotherapy, and why one might need both.

Guilt is hard to release on your own. I’m often puzzled when I hear well-intentioned advice to “forgive yourself,” since in my experience that would be a lot like pulling myself up by my own bootstraps. When I do manage to “forgive myself,” it looks suspiciously like rationalization. I can shift the stone from one pocket to the other and relieve the stress on one aching muscle, but it’s not the same as “laying it all down.”

Until you’ve tried it, it’s hard to imagine the complete release that can come with full, open-hearted confession. And though the act of corporate confession repeated weekly in many churches may seem rote, speaking it creates an opening in the heart that widens over time into willingness, even eagerness to be “cleansed,” released, forgiven, and to find that energy begins to flow again that has been tied up in the arduous business of ego-protection and self-deception.

It’s certainly possible to give and receive forgiveness without benefit of church. But within the church a dimension of forgiveness is taught and practiced that is peculiar to Christian worship. Forgiveness, as the church understands it, is a mystery: we are, as Luther put it, simul justus et peccator—completely justified, and completely sinful. The forgiveness Christ offered and the church makes available is absolute. Though there may be work to do on a human level, once we are “clothed” in Christ’s righteousness, we can walk in freedom, straight to those places where we have amends to make, and make them with lighter and more hopeful hearts. We can afford to confess because confession doesn’t mire us in shame, but lifts us into sure and certain hope and a life of gratitude.

These are theological truths that can only be grasped in faith, but they’re worth exploring even for the unbeliever, especially when therapy has worn thin and relationships are frayed and you find yourself pretty sick of your own addictive habits. Kneeling in a healthy church and reading with others that we have sinned “in thought, word and deed, by what we have done, and by what we have left undone” may both reframe the pain of guilt and relieve it.

One form of confession seems to me an especially rich reflection on the nature of sin (a word we’re unlikely these days to hear spoken without irony anywhere outside the church). It includes these lines:

We repent of the evil that enslaves us, the evil we have done, and the evil done on our behalf. Forgive, restore, and strengthen us through our Savior Jesus Christ, that we may abide in your love and serve only your will.

The first time I heard it, I thought of the drone strikes, white-collar crime, and shady corporate practices I like to condemn, and took instant account of my own complicity. One dimension of sin is the general pollution we all live with. I look at smokestacks spewing toxins into industrial communities or at contaminated rivers or orchards where pesticides leave residues on human skin and realize that the “goods” I take for granted involve me in evils I need to recognize—not with personal shame, perhaps, but with determination to work, once I am “forgiven, restored, and strengthened,” to help stop the harm and heal the earth we share. These concerns are large and weighty. A healthy church equips us to tolerate an awareness that could be crushing if we tried to sustain it all alone and then to act.

A healthy church will invite you into countercultural community. It won’t be an extension program in civil religion. It won’t (and I know there are faithful folk who disagree) fly the national flag in the sanctuary. It won’t stamp its seal of approval on “our way of life,” whatever that has come to mean to comfortable North Americans. It will “afflict” the comfortable. It won’t offer cheap grace. It will help you share—and want to share—accountability for practices that affect the vulnerable. It will expand the repertoire of questions you raise about what is “normal” in the culture you inhabit. A healthy church will look at norms with a critical eye, holding them up to the light of Christ, which involves deep reading of Scripture and deep engagement with biblical ethics. It will lift you out of your cultural landscape enough to take a long, even transcendent, view of it. It will lead you to identify with and act on behalf of the disempowered—migrant workers, prisoners, people with no health insurance, people whose lands and water have been expropriated or contaminated, underpaid labourers, victims of domestic abuse. The list goes on. A healthy church will have the conversation and invite you into it. It will provide you with dates and local leaders and action plans. It will teach you to pray as you go.

Some churches are sanctuaries where immigrants and undocumented workers can find safety and compassionate help while they figure out survival strategies. Some churches participate in projects organized by Habitat for Humanity or the International Rescue Committee or local homeless shelters. Some organize their own versions of such endeavours. One example of imaginative, humble service is our church’s taking over a laundromat once a month, arriving with stacks of quarters, letting it be known that homeless folks can get two loads of laundry washed and folded while they wait. Some pack lunches. Some repair and distribute bikes. Some supplement medical care through parish nursing. The list is long. Many of these things are being done outside churches, of course, but when church people do them, even if they say nothing about Jesus, and often they don’t, the love, humility, convicted consciences, and real joy in service that animates their efforts rarely goes unnoticed.

Where government falls short, the church often steps in. If you look into the “breach,” wherever it gapes, you’re likely to find church people who have leapt into it once more.

A healthy church will give you access to a treasury of words and music. It will bring you into a centuries-old conversation that includes the whole “communion of saints.” Where else are you likely to encounter words like “blessing” or “grace” or “parable” or “holy” or, for that matter, “shibboleth” or “Sabaoth”? Where else are you likely to encounter a conversation that takes you to the ancient world and back, bearing gifts for the present, sometimes wrapped in antique language?

Among the most memorable sermons I’ve heard are a few that focused on a single word or phrase from Hebrew or Greek. One drew attention to the word schizomeno—meaning in Greek “ripped open.” It occurs twice in the Gospels: once when the temple veil is torn the day of Christ’s crucifixion. The other is when “the heavens opened” upon Christ’s baptism. But they didn’t just “open.” They were ripped open. God broke into history with a voice and an act of salvation unlike any other. The drama of that moment would be easy to overlook without the guidance of someone who struggled through seminary Greek in order to help us read more deeply the challenging, mysterious, much-maligned text we call holy.

In that text the church is guardian of a cultural treasure like no other. There are sacred texts in other traditions, to be sure, worth study and reflection. But this one is unique in its multiplicity of sources, its rich, ragged stories, sometimes riddled with gaps, its many literary genres, in the way it gives access to a God who will not be reduced to human dimensions and in the simple fact that it’s a taproot of Western culture. It is the source of archetypes, conceptual structures, metaphors, and mythic symbols that give our psychological and social lives shape and depth. Seventy-five translations of the Bible still exist in English. One can spend many months in Bible study considering what difference the differences among them make.

To study the Bible with people of faith is to see it not only as an object of academic or antiquarian interest but also as a living word, a source of intellectual challenge, inspiration, comfort, uncomfortable ambiguities, and endless insights for people who gather in willingness to accept what seems to be God’s invitation: Wrestle with this. Healthy churches wrestle, working out their salvation over coffee and concordances, knowing there is nothing pat or simple about the living Word, but that it invites us into subtle, supple, resilient relationship with the Word made flesh who dwells, still, among us.

Healthy churches are places of divine encounter. The disenchanted who have suffered from warped pieties and the skeptical who haven’t met a believer who meets their standards of intellectual integrity may simply not believe this. Nor might a person who has a thriving meditation practice rooted in non-Christian tradition: it’s become distressingly easy to point to churches that don’t, in fact, foster the silence, contemplative practices, or sustained, unstinting prayer that deepens and widens awareness beyond rationality or convention. But a healthy church does those things. It provides a place, a way, an invitation, and a sacred space in which, if you come with an open heart, you may find yourself, in spite of yourself, practicing the presence of God.

Singing is one way to “enter into God’s courts.” Few places are left where people gather and sing. Yet neuroscientists say that singing together promotes integration of brain functions, alleviates depression, and promotes mental health. When we sing we learn viscerally and audibly what it means to be “one in the Spirit.”

Hearing sacred texts read aloud also brings us into alignment with others who inhabit the same story. It is our story—all of ours—available to be entered and explored like a great territorial preserve. I have sometimes found that hearing a familiar phrase read aloud—”Be not afraid,” or “Come and see,” for instance—suddenly emerges in the context of a service as personal address. We gather in church because private, silent reading is not enough: we need to hear the living word breathed by a human voice.

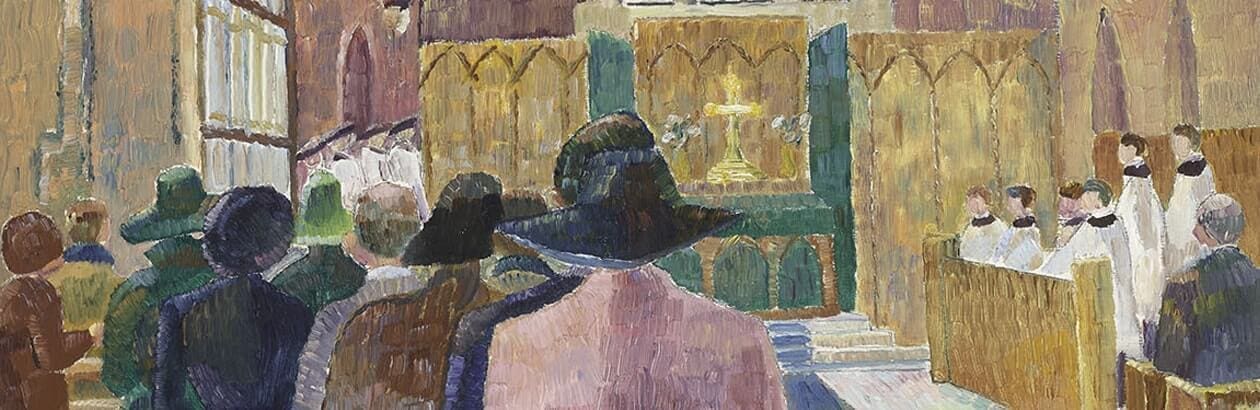

And the Eucharist, the Lord’s Supper, Holy Communion—whatever name it is given in a particular denominational tradition—has become, for me, Protestant that I am, the moment of encounter I most eagerly await when I go to church. When I walk forward and kneel at the Communion rail, though other ways of receiving the sacrament have their logic and legitimacy, I make, each time, a new act of consent to God’s invitation to participate in divine life. I am reminded again of the shocking intimacy expressed in the words “This is my body. Take. Eat.” The message each time seems to me something like, “Do you get it now? How utterly I enter into your very being, your body and breath, to make you a Christ-bearer?”

I know a number of people who hesitate to talk about Jesus or Christ, but are comfortable with the term “Christ-consciousness,” meaning a higher state of awareness and awakedness to divine presence within and all around. Many mystics have testified to extraordinary moments of vision, transport, being subsumed in the Light, filled with the Spirit, empowered in sudden, inexplicable ways. As far as I know, none of them, Christian or non-Christian, has experienced the benefit of such experiences without two prerequisites: humility and community. We gather in churches because our combined will and willingness, our collective energy, our voices attuned and our attention directed toward God, enable something to happen that is far less likely to happen alone or at random.

Distracted, reluctant, confused, or apathetic you may be on any given Sunday, but if you go, something will happen. A word, a phrase, a flicker of candlelight, a gesture, an image, an extended moment of silence—all these have their effects. On Sundays, and they are not infrequent, when I don’t really feel like getting dressed and going to church, but do it anyway, I invariably leave with a gift I could not have foreseen. It’s not always the sermon—a good sermon is hard to find. And sometimes the readers read poorly or the person behind me can’t stop coughing or someone won’t take the crying baby outside. But underneath the distractions and irritations runs a current so strong it carries me in spite of myself. I float in mighty waters.

Not all churches are alike. Not all churches are healthy. The troubles that afflict unhealthy churches are nothing new: they are dishevelled or diseased or fatigued or torn by infighting. But even those churches contain within themselves the seeds of renewal. They aren’t simply dying institutions, irrelevant and poorly run; they are cell and tissue of the body of Christ. Within them people we may not enjoy but must engage with are, in very fact, brothers and sisters who belong to us and to whom we belong by a tie stronger than blood. All of us who labour and are heavy laden come to receive “the gifts of God for the people of God” and find that God’s people are also ours.