M

The Lord our God, the Lord is one. Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength.

—Mark 12:29–31

Blessed is the man . . . whose delight is in the law of the Lord, and who meditates on his law day and night.

—Psalm 1:1–2

Christ is the culmination of the law.

—Romans 10:4

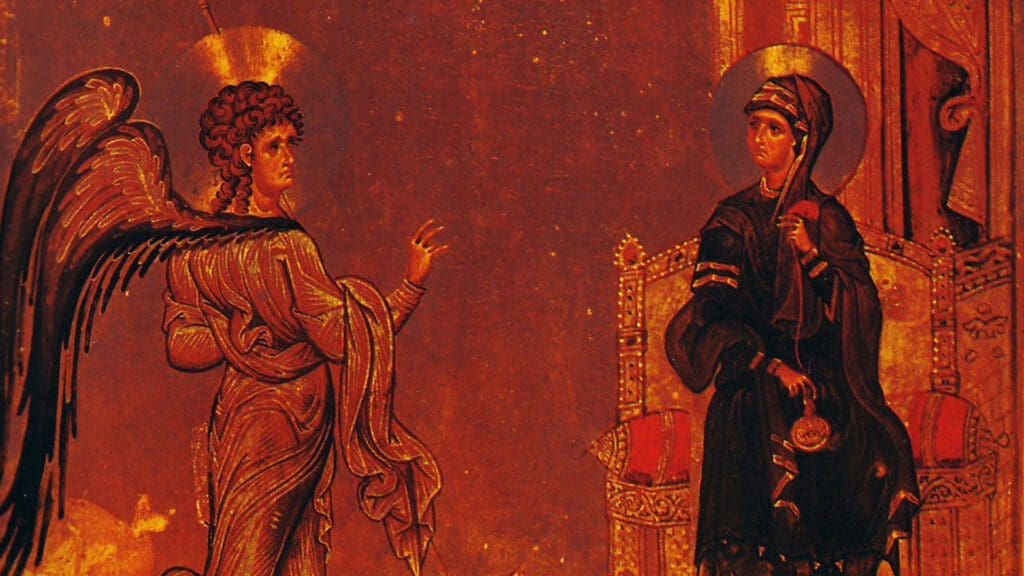

Mary

There are two humans who are not also God who are mentioned by name in the ecumenical creeds. One is Pontius Pilate, who in cowardice condemned Jesus to die. The other is Mary the Mother of God. Not only is she the only woman mentioned in the creeds, but her sexuality is also explicitly referenced. Jesus “became incarnate by the Holy Spirit and the virgin Mary.” Human sex was not the cause of Jesus’s conception, and Mary became Jesus’s mother without ever having had sex.

Mary’s virginity is highlighted in the creed to show the miraculous nature of Jesus’s birth. We are being asked, when we say the creed, to speak alongside Mary the words “How can this be?” And to remember Gabriel’s words: “Nothing is impossible with God.”

There is also a long tradition of focusing on Mary’s virginity in terms of her purity. This isn’t wrong, and despite the vast overreaching and abuses of this concept of purity—and they are legion—it’s a fair reading. But we can’t fully appreciate Mary’s role in the history of salvation until we come to grips with the historical fact that Mary was a young, unmarried woman who did not have sex and yet found herself with child.

Imagine you’re a sixteen-year-old Jewish girl who’s just missed her period. You’re starting to swell and people start to notice. And not only do people start to notice, but people start to talk as you pass by their house to get the day’s water. Now ask yourself: What do you say to those people? What do you say to the women you’re drawing water with? What do you say to your betrothed? To your parents? To fully appreciate the magnitude of where Mary is, you have to imagine yourself speaking the truth to any one of those people: “I didn’t sleep with Joseph. I didn’t sleep with anyone. God made me pregnant.” If that doesn’t sound preposterous, imagine a pregnant teenager saying that to you today.

It is undeniable that Mary’s pregnancy would have been clouded with suspicion, slander, and shame.

I have no idea how Mary actually lived her day-to-day life as Jesus was growing in her womb, but in my meditations it seems unlikely that, apart from Joseph and those closest to her, she spoke much about how she came to be with child. Her ponderings and treasuring of the angel’s words and her post-annunciation visit to Elizabeth and Zechariah seem to indicate much more reticence and circumspection.

It is undeniable that Mary’s pregnancy would have been clouded with suspicion, slander, and shame. She would have lived for most of her life (maybe all of it) enduring murmurs and whispers, maybe even been wary of travelling alone, or in places where there were crowds and rocks on the ground, despite never having broken Jewish law. She had no way to intelligibly defend herself. This false shame would have been a heavy cross to bear. For Mary her pregnancy itself would be a type of cross. She bore in her own body the scandal of the incarnation. In this way, she was the first follower of Jesus—and also the first recipient of Jesus’s grace. Despite this cross (or maybe because of it), Mary delighted in and magnified the Lord. In the conception of Christ, we already see God reversing the curses of Genesis 3. The curse placed on woman was that her desire would be for her husband, and that her husband would rule over her. “Rule” here should be understood in the same way that Proverbs 22 says that the rich rule over the poor—by dominating and oppressing them. The picture is one of the husband “lording it over” his wife. Mary’s desire was for the Messiah, and yet God did not lord it over her; rather, he submitted himself to be carried in her womb, and she humbly consented. It was not the husband’s will that made this child, but the union of God’s will with Mary’s. The way the Holy Spirit works within us to fill us with grace is a dynamic and mysterious thing, but it never coerces. The Holy Spirit is God, and God is love; it is not in the nature of love to impose.

Our age is deeply concerned about shame associated with sexual deviancy and the pain that comes from sexual domination, and rightly so. Looking at Mary’s experience from this perspective, we see the grace and liberation of the gospel already there at the very locus of these kinds of painful experiences. And it helps us not just see but also participate alongside a fellow follower of Jesus in delighting in and magnifying the Lord, even in the midst of shame, slander, and an inability to offer a response that will satisfy the world.

So as we say the creed, let us recall this side of Mary’s virginity and allow it to deepen our wonder of our Lord and Saviour, who began his work for us and for our salvation even at conception. Let us also recall that it is plausible that the first cross borne by the first follower of Christ was sexual in nature. And yet for her the person of Christ was answer enough, and the source of strength and consolation in a hard life. Let us be more like the Mother of God in nurturing her relationship with Christ.

Joseph

One of my favourite poems, by one of my favourite poets, Les Murray, is called “The Say-but-the-Word Centurion Attempts a Summary.” In it, the centurion from Matthew’s Gospel tries to describe Jesus for his Roman audience.

One of the more jarring names given to Jesus by the centurion in the poem (alongside my favourite, “soul-usurer”) is “divine bastard.” At first blush it might offend. But the term is jarring because, while a term of derision, technically it’s true. A bastard is a child born out of wedlock. Jesus is, worldly speaking, a bastard. His father is unknown. This places him in an awkward position, but it places Joseph in an equally awkward position, perhaps more awkward given the social context. The verses from Scripture that describe this position are extremely short. Yet you get the sense that Joseph, a man who almost certainly knew Scripture well, was deeply troubled. Dreams come, after all, when there are many cares. And what would have been the nature of his cares? Clearly he cared deeply about Mary and did not want to expose her to the social shame that would have been compounded by a public divorce—an aspect of Joseph’s marital love for Mary that is underrated in my opinion. You can imagine his other cares and doubts as he went to bed the night of his dream: doubts about his worthiness, doubts about the nature of the woman to whom he was betrothed, wondering who it was that had slept with his fiancée. But what would not have been in doubt was the fact that Mary was pregnant and that he was not the father.

And then the angel: “Joseph, son of David, do not fear to take Mary as your wife, for that which is conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit. She will bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins.” And then the doubts are gone. Well, at least those doubts.

The relief of those doubts—the liberation you can imagine would come with knowing that not only did your betrothed not cheat on you but HOLY SMOKES SHE IS BEARING THE MESSIAH!—would do nothing to stop the rumours that would, inevitably, start to flow: either that you’re a cuckold or that you yourself got your wife pregnant out of wedlock and so violated the law.

Joseph would have been the first, and perhaps the best suited, to understand the promise that is given to us later in the Gospel of John: that we are “children born not of natural descent, nor of human decision or a husband’s will, but born of God.” Joseph, being the husband in question, would have known this in his flesh: the NIV, which I’m quoting from, uses the sanitary “human decision” in lieu of the more carnal “will of the flesh,” which depicts not just human bodies but—and Scripture bears this out—sex itself. Joseph’s acceptance of and even delight in Mary’s pregnancy is all the more powerful given the echoes of Genesis 3 mentioned above. As with Mary, Joseph is involved in the reversal of the curse of “ruling over,” which is a curse on men as much as it is on women. Husbands are not intended to lord it over their wives—quite the opposite. Joseph is the husband of Mary, and the child was born not of his will but of a union of the will of God with that freely given by his betrothed. Like Mary, his desire was for the Messiah, and he put his own desires of the flesh aside for the sake of his wife, and ultimately for Jesus. Whether one is Roman Catholic and believes that this was true for his whole life, or whether you take a more reticent reading that doesn’t exclude eventual union, Joseph’s will in the birth of our Lord and Saviour was exercised in obeying God by marrying Mary and loving her and their son. And while we might skip right over it, he did this not just in his mind but in his body by refraining from sex. Joseph, a child of God, was enabled by the Spirit to be a father to a child born not of his flesh but of the comingled will of God and Mary. This love triangle—one that is very much absent sex—is a microcosm of fruitfulness through self-denial, a cluster of ideas beautifully and succinctly captured in the words of the Athanasian Creed: “He is God from the essence of the Father, begotten before time; and he is human from the essence of his mother, born in time; completely God, completely human.”

The world saw social deviancy, but they knew they held the Christ, and they were satisfied.

There was nothing Joseph could do to rectify the social stigma for himself or his wife. Again, just imagine telling the truth: “An angel told my wife she was going to be pregnant, the Holy Spirit made her pregnant, and an angel told me that he’s the Messiah.” Telling the truth would make an awkward situation worse. It would make you hesitant to say anything. You’d have a life ahead of you of being that guy—the guy who married the crazy woman who said God made her pregnant (and believed her). You and your wife would get all the social stigma that accompanies an affair of the flesh, without the physical pleasure of sex. You’d maybe get some pity, or some grudging admiration, but you, man, are always going to be a bit of a social risk.

Perhaps this offers some insight into the nature of sexual liberation that comes to us through giving ourselves wholly to Christ. It is, in some sense, a liberation that is necessarily, maybe always, accompanied by worldly burdens. Men, in particular, how willing are you to be like Joseph? When was the last time you refrained from sex to dedicate yourself to prayer and God?

The sexual liberation we see in Scripture begins and persists in a relationship that most people will not be able to see. This does not mean it doesn’t have public consequences, nor bodily consequences (we’ll see how false that is as we meditate on Jesus), but it begins with the internal knowledge that one is free through union with God, who is real, true, and present with you; and in the eyes of the world it will be seen socially as a restriction or a burden. A worldly view of Mary and Joseph’s story is completely and utterly different from the real truth. In this sense Jesus’s conception becomes a parable: “Though seeing, they do not see,” Jesus says in Matthew 13. “Though hearing, they do not hear or understand.” It is, sexually, topsy-turvy. Mary, by her grace-filled will and decision, was a cause of Jesus’s conception. As a woman, she adopts the active role in the conception of Jesus usually reserved for men and is more of a woman because of this. Joseph, through actively accepting a passive role of chastity through celibacy, is more of a man because of this. In their case, the world saw social deviancy, but they knew they held the Christ, and they were satisfied.

Jesus

Which brings us to Jesus.

I have found that in some circles it is considered uncouth to talk about Jesus’s body as a human body, and not some sort of strange spiritual thing you can also touch. But Jesus is human. He ate, he drank, he pooped. In fact, Mary and Joseph would likely have been familiar with that surprising, but very normal, newborn activity that necessitates the words “we’re going to need a bath for this one.”

But as taboo as it is to mention the very normal and human fact that Jesus had to use the bathroom, it is even more taboo to talk about Jesus when it comes to sex.

Sadly, many people attempt to address this heretical squeamishness about Christ’s body by going the total opposite direction and . . . just making stuff up. A classic example is Harvard scholar Karen King, who claimed to find a missing gospel that indicated Jesus was married (she later admitted it was a fake). But there are others who simply cannot believe that Jesus was a virgin. “How do we know he didn’t have sex?” is the question that gets asked here. I had this conversation with someone in my church community recently, and it echoes things I heard regularly in grad school. The answer is that all the evidence that we have (not to mention all the evidence that Christians consider authoritative, though I don’t think the difference means much in this situation) tells us he didn’t have sex. No reasonable person can believe otherwise.

Our sexuality is part of what it means to be human. I therefore don’t think it’s reasonable to believe that Jesus was a non-sexual being.

I find these types of approaches to be as troubling as those who can’t handle the possibility that Jesus needed his diaper changed. Many simply can’t conceive of the possibility that one can live a full, fully human life without sex. Yet here we have Jesus, of whom several things are understood to be true: That he is God. That he is the fullness of what it means to be human. That he never had sex. That he was born of a virgin, died a virgin, and was raised from the dead a virgin. That he is still a virgin and always will be.

And yes, he did this fully as a human. Our sexuality is part of what it means to be human. I therefore don’t think it’s reasonable to believe that Jesus was a non-sexual being. The book of Hebrews tells us not to buy the lie that Jesus was “unable to sympathize with our weaknesses,” and I see no good reason why we should exclude the weakness we feel when we are tempted sexually. Why? Because Jesus is “one who in every respect has been tempted as we are.” What compelling, orthodox case can be made to exclude sexual temptation, of any sort, here? It is incredibly comforting—and empowering—to know that, in the midst of your temptation, Jesus is there with you because he has experienced the same temptation. He allowed himself to be led into temptation, and he was delivered from evil. Now there are some who will, rightly, point out that because Christ was without sin, his temptation was categorically different. Christ, after all, did not have to deal with what theologians call concupiscence—that is, the tendency, inherited from original sin, to desire that which is contrary to God’s will. This is true, of course, but the mirror image of that danger is to understand that Christ was not free. Christ, as Scripture tells us, was the new Adam. He was free to sin. He could have if he wanted to. Yet he did not sin. And he did not sin because he did not want to. This did not make him less human but more human. He had no desire to because he was satisfied with the love of the Father and the Spirit. What is so incredible—and hopeful for those of us who struggle with temptation—is that those who are in Christ have the same Spirit. You are, as Scripture says, no longer a slave to your ill-formed and harmful desires. You are free to be like Christ, because he has given you access to the same love that enabled him to resist temptation. He is with you in your temptation not just in spirit but through his bodily experiences, through the Spirit.

While Christian sexual liberation is first internal and personal, it also has profoundly physical and social implications. Louise Perry opens her (really good) book The Case Against the Sexual Revolution with two devastating quotes. The first, from Mary Wollstonecraft in the eighteenth century, says this:

The little respect paid to chastity in the male world is, I am persuaded, the grand source of many of the physical and moral evils that torment mankind, as well as the vices and follies that degrade and destroy women.

The quote is devastating, I believe, because it’s true. The relationship of our selves to our bodies and of our bodies with others’ bodies is a matter of justice, both private and public. The high correlation—ubiquity is almost the right word—of rape with war makes it a virtual metonym of the “physical and moral evils” described by Wollstonecraft.

Consider the story of Jesus’s interaction with the woman caught in adultery. We’re used to thinking of Jesus’s statement “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone” in terms of sin in general. But would it not be enlightening to see it not just as a condemnation of sin in general but as an incisive condemnation of sexual sin? I think of this especially in light of Jesus’s earlier teaching in the Sermon on the Mount: “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall not commit adultery.’ But I tell you that anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart.” I think it’s fair to suggest that Jesus’s accusation is subtle but specific: “Let him who has never lusted—who is perfectly chaste—among you be the first to throw a stone.” After he asks the question, who is left? Jesus.

I can’t help but think that Jesus would have had his mother in mind as he drew in the sand, waiting for the men he knew were guilty to drop their stones and walk away. He, the divine bastard, would have known that the woman brought to him, in another time, could have been his mother. I can’t help but think that he had in mind his earthly father too, the righteous man who was unwilling to degrade and destroy a woman’s life because of sexual infidelity. Wollstonecraft saw that respect paid to chastity can stand in the way of physical and moral evils, and uphold and protect women. The word “chastity” appears to share a similar root to the word for castration, intentionally making someone sexually impotent. But in Jesus’s case it is chastity—an intentional refraining from sex—that provides the potency which neuters the physical and moral evils that torment mankind and degrade and destroy women.

Jesus’s record of relationships with women throughout the Gospels follows this trajectory. Whether it is his refusal to consider a bleeding woman unclean, his invitation to the Samaritan woman at the well to exchange the insecurity and dissatisfaction of multiple lovers (which is itself an echo of Israel’s infidelity writ large and the Samaritans’ infidelity in particular) for Christ himself, or the incredible story of the anointing of Jesus’s feet, Jesus’s chaste love allows people to become fully themselves.

Luke’s account of the “sinful woman” who anoints Jesus’s feet is a poignant case study of this love. There are multiple readings of who this woman is and what makes her sinful, but a long tradition sees the woman who anoints Jesus’s feet as a prostitute. (In his Gospel, John identifies her as Mary, and although I am going by Luke’s narrative, which doesn’t name her, I will refer to her as Mary as well; the story is about intimacy, so it seems proper to use her first name.) Why would a prostitute come into a dinner party with a very expensive jar of perfume? Why is Mary weeping? Why does she perform such an incredibly intimate act? I don’t know, to be honest. Is she weeping because of her sin? Yes, I think she is, and it is clear from what Jesus says that this is central to her reason for being there. But, again, I think that meditating on the nature of her sin—the selling of her body—should lead us to imagine her mixed tears of grief, relief, and love not as happiness that she has simply received a moral get-out-of-jail-free card but as redemption from the entirety of her life as a prostitute; not just the sins she’s committed but the entire heinous web of abuse and domination in which she was caught.

In spite of years of abuse at the hands of men, she comes to Jesus and performs a deeply intimate act, as soul baring as it is physical—an act that, were Jesus not perfectly chaste, would have been scandalous.

This brings me to the other quote from Louise Perry’s opening, a poem by Hollie McNish titled “Conversation with an Archeologist.” It is in many ways even more devastating than the first, because it shows the ultimate result of man’s lack of respect for chastity.

he said they’d found a brothel

on the dig they did last night

I asked him how they know

he sighed:

a pit of babies’ bones

a pit of newborn babies’ bones

was how to spot a brothel

Yes, selling your body is wrong. But prostitution is—the statistics back this up—something purchased almost exclusively by men. By men who wish to use women for their own selfish reasons. Purchasing sex, in other words, fails to see women as women, as human beings made in God’s image. Prostitution degrades and destroys. And as the poem shows us, it is not just women who are destroyed but the beautiful little trinity of life that comes as a result of sexual union as well. The bones and bodies of babies are broken. The French call an orgasm un petit mort, “a little death.” In light of this poem, the metaphor becomes horrifically literal. The poem might very well have been written about the brothel that Mary worked in. In which case her tears might very well be tears of grief for the way her body has been used; grief for the abuse she’s suffered for years; grief for the cowardice, wickedness, and vice she has witnessed in her clients; and grief for her children, who lay buried next to her former place of work. In that light, it makes her gift—and Jesus—even more beautiful. This is a woman who would have known a creep, and which men were dangerous. And yet, in spite of years of abuse at the hands of men, she comes to Jesus and performs a deeply intimate act, as soul baring as it is physical—an act that, were Jesus not perfectly chaste, would have been scandalous. Feet in the first century were considered intimate and were associated with sex, and the woman’s use of her tears, lips, and hair (which in that culture, as in ours, were also sexually charged) would be seen as profoundly sexual. But because of “her great love,” as Jesus says, Mary’s actions are transformed from a carnal act to a purer, higher love, though no less physical. This is true for all of us. We all have bones buried as a result of our sexual actions. Yet, like Mary, we too can weep tears of grief and joy, because the feet she kissed walked into hell, gathered those bones, and gave them the life they lost.

The horrors of sexual sin—not just the moral turmoil or the moral callousness, though by no means excluding them—are taken up by Jesus, who knows each one of our sins intimately and yet loves us as much as he loves Mary. And that, I think, is what is ultimately liberating. We are no longer just prostitutes or lecherous stone throwers. The children who have died because we were more interested in little deaths than little lives are raised from the dead. And we can be too.