A

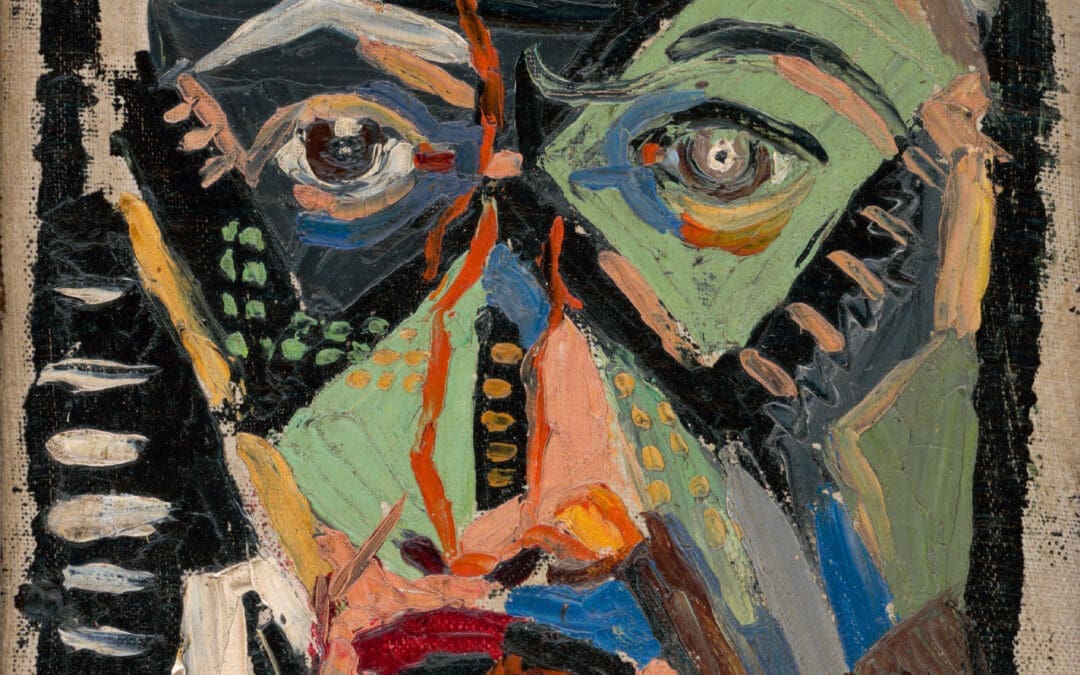

A seventh-century icon of the Annunciation, a moment described in Luke 1:26–38, hangs in the oldest continuously used monastery in the world, St. Catherine’s, atop Mount Sinai in Egypt. Painted on wood using gold and other natural materials, this icon encapsulates the moment when, according to Scripture, the angel Gabriel told Mary she would conceive a child—Jesus, the Son of God—through the power of the Holy Spirit. In this image, Mary is sitting on a throne and is holding a needle and thread, spinning yarn. Her gaze turns toward the angel Gabriel, who is moving toward her. Below Mary’s throne are fish.

This icon frames a moment in time—the Annunciation—but all icons create a timeless landscape of symbolism. The background is gold and flat, eliminating any illusion of depth. This is a symbolic representation of the heavenly realm, which exists outside time and space. Iconography therefore demonstrates how historical events become part of salvation history, making icons works of art but also windows to eternity. The iconographer Aidan Hart writes that “iconography is always historical, charismatic and eschatological.” Feasts like that of the Annunciation not only recall a historical event but also make the grace of that event available to us now. “The divine events,” he says, “happen in created time (chronos) but flow forwards to us in divine time (kairos).”

How might icons and feasts that feature early Christian understandings of Marian piety and doctrine help us think about the topics of femininity, sexual difference, and motherhood today?

Mary in Modernity

Philosophers such as Charles Taylor and Alasdair MacIntyre have written that one of the key elements of modernity is understanding freedom as autonomy. Dependence is rejected and self-expression is exalted. Many feminists such as Judith Butler have written that women’s liberation requires rejecting social roles that come from biological differences between men and women. For many, therefore, motherhood is exclusively a choice. But what is it exactly about rejecting social roles, framing relationships as choices, and exalting the self that leads to liberation? Rejecting prescribed roles from the past does not answer the question of how to live a good life.

As a cradle Catholic who often avoided theological discussions of Mary with Protestants, I was surprised to learn that my mostly Protestant students are highly intrigued by depictions of popular forms of Marian devotion in modernity. When I co-taught a class on religion and immigration with the late African American religious historian Albert Raboteau, we read Robert Orsi’s Madonna of 115th Street, a social history of Marian devotion among Italian Americans in East Harlem at the turn of the twentieth century. Orsi depicts the days and nights of the feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel: men carry a statue of the virgin on a platform; women crawl in front of her on their knees, begging for aid. Poverty, exclusion, family division—all their wants and hopes pour out before this lady, the mother of Jesus. In these devotions to Mary, Orsi says, Italian Americans see a parallel to the maternal authority of their grandmothers. If men had public authority, women had the moral authority of the home. Age, suffering, and a keen focus on home and family produced in the women of those communities a foundation of feminine wisdom.

For many, motherhood is exclusively a choice. But what is it exactly about rejecting social roles, framing relationships as choices, and exalting the self that leads to liberation?

Although I feared I would have to respond to theological objections to Mary’s exalted place in Italian American Catholicism, the stories instead provoked questions among my students about what Protestant churches might be able to learn from traditional devotions to Mary. To explore these questions further, I developed a class on devotion to Mary. Tim Perry and Daniel Kendall’s book, The Blessed Virgin Mary, provided a guide for us to start this journey. We did not avoid questions that Christians of the first centuries after Christ also pondered: Is it possible that devotion to Mary might displace the centrality of Christ to our salvation? While mindful of excesses in some forms of Marian piety, why is it important not to ignore Mary either? These debates divided the early church fathers, divided Protestant Reformers from Catholics, and even divided the Protestant Reformers from each other.

We also studied the history of Marian icons—images that were intended both to communicate the events in Scripture and to foster devotion to Mary—which helped us all to put ourselves in the place of Christians from all centuries who have sought to know Mary the Mother of God in a contemplative, mystical way. Because Mary is so clearly present at the Annunciation as a mother, learning about the iconographic tradition of this key moment in salvation history opened ways for my students to compare past and present visions of motherhood, as well as competing visions of motherhood in modernity. Church historian Jaroslav Pelikan has written that Christians have likely depicted the Annunciation more than any other event in Scripture, reminding us that we are meant not just to read Scripture but also to meditate on its meaning, often with the aid of visual images.

The traditional theological meaning of Annunciation icons such as the one at St. Catherine’s is that God’s grace does not work only on our minds or hearts; Mary’s acceptance to be the bearer of the Word made flesh means that all created matter—including our bodies—can be sanctified. In the icon, Mary is spinning yarn. Being occupied in the world need not hinder our ability to hear God’s call.

All of human nature, soul and body, is thus a sign, a window to a deeper reality: Mary accepts and cooperates with God’s mysterious revelation of himself with her entire human nature, accepting him into her very body. In the book Mary: The Church at the Source, Pope Benedict XVI rejects the idea that sexual difference is an “irrelevant triviality” and fears that if we negate biological differences that exist in nature—including sexual differences—we will then treat all of nature as something we can manipulate. As a reality rooted in sexual difference, biological motherhood is a gift of creation; it is also a sign. If we negate biological motherhood, we risk negating the feminine dimension entirely, along with the qualities of patience, humility, and attentive listening associated with feminine wisdom. Modern types of feminism that reject biological motherhood as powerless dependence refuse to recognize uniquely feminine gifts, arguing that dependence reinforces patriarchy. Yet who among us is truly independent? Each of us began our life in the womb of a woman. The idea that women’s liberation requires leaving biology behind, Benedict XVI asserts, “strikes a blow” against our deepest being.

Celebrating Mary’s contemplative, hopeful obedience at the Annunciation helps us remember that the church she symbolizes and models is not a political organization focused exclusively on historical time, but a place that allows the divine to enter human history. The modern, activist mentality is in danger of rejecting our dependence on God. The church has an important social dimension, but it can never be restricted to that dimension, as if she were just an idea or a project whose purpose is to change the world. The church is meant to be a home of a people who listen for God’s word with hopeful expectation.

Mary’s yes at the Annunciation indicates that she is a woman who knows how to listen, and thus how to read signs. Recovering this Marian imagery is crucial to restore the church’s feminine dimension—the church as a home, a place of leisure, worship, rejoicing, and wisdom, where we can come together in darkness and sorrow.

Obedience and the Logic of the Gift

But what precisely is the meaning of obedience in the context of Mary’s yes at the Annunciation? Many Christians—perhaps following John Calvin—have been taught to think that Mary was nothing more than a vessel, a passive, inert container for God’s grace. But a different understanding of Mary’s obedience held by the early church and reaffirmed by recent Catholic popes like St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI, along with most Protestant thinkers past and present, is that humans have the freedom to cooperate with—or to reject—God’s grace.

Although Scripture doesn’t tell us what Mary was doing when the angel Gabriel appeared, icon painters who depict Mary busy spinning yarn suggest that her worldly concerns did not prevent her from being attentive to God’s call. Mary’s obedience signifies that prayerful discernment is needed to exercise true freedom, which is found not in self-assertion but in responding to God’s call and offering ourselves and our work back to God.

Christian tradition has held that Mary is the most “blessed among women” (Luke 1:42), and indeed among all creatures, because by her yes she became the fruitful soil in which the seed of the Word—Jesus—became flesh. In hearing God’s call and freely obeying, Mary becomes an icon of all humanity. God’s Word enters the world through Mary’s welcoming acceptance of his will. Mary is a model of letting God’s word awaken in our souls, slowly purifying us to be able to hear what he is saying to us. God’s action in the world is real, but also mysterious. If we seek to subject God’s plans to our strategies, we may miss his inspiration.

At the Annunciation, Mary shows that the response to God’s word must be personal. Fulfilling our destiny of salvation is not just external rule-following but becoming who we are called to be. Returning to God is like coming home. As Benedict XVI explains, coming to Christ is meant to be not just an act of will or a choice but what he calls “a bond ex toto corde—from the depth of the heart—to the personal God and his Christ.” Faith is not imposed, because faith is born of love. The church must preserve this feminine dimension of faith. From this dimension comes what St. John Paul II called the logic of the gift.

When Mary pondered the angel’s words and responded yes to bearing the Son of God, she gave her entire nature back to God, becoming truly herself. The true meaning of freedom is not mastery over ourselves or our world but our capacity for and act of offering ourselves to God. Louis Bouyer explains that “it is only by being absorbed in the eternal thought that God has of us in his Son from all eternity that we can hope to become truly ourselves: to realize the plan, the divine vocation that alone can give meaning, his meaning, to human life.”

We are not even masters of our bodies. We are a unity of body and soul. The endless search for individuality that comes from rejecting motherhood and femininity out of fear of dependence runs the risk of rejecting this unity, which is meant to be sanctified through self-giving relationships.

In the preface to The Madonna of 115th Street, Orsi writes that modernity has so emphasized the primacy of material conditions that we fail to see that for the Italian Americans he writes about, the world is full of signs of God’s presence among them. When we reduce social phenomena like the festa of Our Lady of Mount Carmel to nothing but an expression of worldly alienation due to poverty or exclusion, we lose sight of the humility and dignity of people whose faith is based on trust. Perhaps popular devotions to Mary move so many people today because our hearts long to believe that God is present in the world, even when our actions or activism do not seem to bear fruit.

We are not masters of the world. We are creatures of God. Trusting in God includes acknowledging that we do not have absolute freedom and total control over nature. Motherhood is a sign of this dependence on God. Although embracing this dependence challenges our modern notions of autonomy, acknowledging our dependence on God means we are also called to a deep unity with others that goes beyond instrumental manipulation for our own ends.

We are not even masters of our bodies. We are a unity of body and soul. The endless search for individuality that comes from rejecting motherhood and femininity out of fear of dependence runs the risk of rejecting this unity, which is meant to be sanctified through self-giving relationships. “The soul,” said Edith Stein, “is naturally bound to matter.” We may have mystical experiences, but the eye of the soul can never be detached from the body. Although we are conscious and can make choices using our will, the ground of the body puts limits on us. Our bodies are indeed vessels of the soul but also themselves in need of sanctification.

The Marian Fugue

Acknowledging some limitations on our freedom opens up a deeper way of living. A fugue is a musical form in which one or two themes are repeated through the continuous interweaving of different voices. This concept can help us think about listening for God’s word with Mary, who knows her being has conditions set by nature yet develops herself through the interplay of listening, silence, and intimate relationships with others.

As Caryll Houselander writes in The Reed of God,

The history of the Incarnation is like a fugue, in which the love of God for the world is the ever-recurring motif. It was uttered first in Mary’s voice, in its very simplest phrase, like a few single notes. A few words spoken to an angel and heard only by him: “Be it done unto me according to thy word.” Then, like the pause that measures music as truly as the sounds, the word of God is silent; for nine months it is inaudible. It is the pause during which the opening phrase grows within us in loveliness, preparing our minds for the coming splendour.

The harmony of a fugue is not the result of a unity that eradicates tension or difference, but rather a unity that emerges from point, counterpoint, movement, and silence. Motherhood resembles a fugue, an intimate interweaving of two people who nonetheless remain distinct.

When a PhD student in church history visited my class on ecumenical devotion to Mary, she was just over eight months pregnant. With her hand resting on her belly, she described how her whole body had changed because of her biological motherhood. This new life was totally dependent on her until birth, yet she knew this child was growing in her in a way she could not control. This mother’s participation in the new life of her child will change and develop: the child will both depart from her and yet always be intertwined with her; they will always have a special bond.

We need not fear the sexual difference that gives rise to biological motherhood if we embrace the fugue-like reciprocity of male and female as a sign of the dynamic love story between God and his people. Sexual difference in nature is a sign that our being is completed through the gift of self.

After the Annunciation, Mary waited while the child Jesus grew in her womb. But that time of patient silence was not purely passive. Mary listened for God’s word in the depths of her being. The movement from conception to birth is a gestation, a growth in which the mother participates. Mary can help us see the pauses in life not as emptiness but as pregnant pauses, preparation for something significant. Mary knows how to read signs. To know the meaning of our lives, we need to listen not just to the movements but to the silences. In those silences, our lives can be spun into a story bigger than us. Just as a mother recognizes her child’s voice as if it were still a part of her own voice, Mary hears each of our voices, like a great chorus, and hears the Word of God—her son Jesus—alongside our voices. In her attentive listening, Mary unites our lives to the life of Christ.

Transformed by Grace

As I noted above, Mary is much more than just a passive vessel; she is the one who receives Christ into herself and bears him to the world. St. Paul’s reference to the church as the body of Christ in 1 Corinthians 12 indicates that we come to Christ as fully embodied persons—not just spirits. If we recover the Marian, feminine dimension of the church, we will be better equipped to see the church not merely as an organization (something formal and rigid) but as a living organism (something alive, organic, close to our hearts).

Benedict XVI writes, “The Church is the body, the flesh of Christ in the spiritual tension of love wherein the spousal mystery of Adam and Eve is consummated, hence, in the dynamism of a unity that does not abolish dialogical reciprocity.” The Annunciation is “the mystery of the listening handmaid who—liberated in grace—speaks her Fiat and, in so doing, becomes bride and thus body.” In that one sentence, Benedict XVI uses a number of theological concepts: mystery, listening, handmaid, liberation, grace. These concepts contrast with “a purely structural ecclesiology,” which he fears “is bound to degrade the Church to the level of a program of action.”

Apart from a recognition of the female and male in nature, and without an appreciation for the dialogical, spousal images of Christ and his body—the church—our journey toward Christ becomes individualistic and rationalistic, devoid of mystery and listening. In imitating Mary’s longing for God, her receptivity to God’s word, her obedience, we come to Christ not just as spirits and not just as individuals, but with our bodies and as members of the body of Christ.

To live a life of simplicity based on trust in God, we need to be transformed by grace.

It was through great saints of the twentieth century who struggled with suffering and evil—John Paul II, Edith Stein, and Mother Teresa—that I discovered that the church is not simply a vessel to direct ideals for social change; rather, the church uniquely offers a life of prayer supported by a body of people, past and present, following Jesus. Practicing Marian piety—praying the rosary, celebrating Marian feast days, venerating Mary in daily prayers like the Angelus—has helped me see how essential a life of prayer is to make our exterior work fruitful. Apart from God, even work we do with good intentions can become prideful or competitive. Remembering Mary’s femininity and motherhood reminds us that if we have no time to enter into God’s time, then it’s easy to reduce God to an instrument of power, achievement, or status. With a purely activist, masculine mentality, faith loses the feminine, affective dimension of prayer, surrender, and dependence on God.

To live a life of simplicity based on trust in God, we need to be transformed by grace. Marian doctrine and devotion help us not just to know about Mary but to know Mary as our own mother. We can all imitate Mary’s faith and allow ourselves to be transformed by grace in order to become living icons of her obedience and trust at the Annunciation. In Mary the Mother of God, we can all see a model of hopeful expectation, an openness to mystery, and the self-gift that weaves together our lives with the divine fugue.