L

—Meister Eckhart

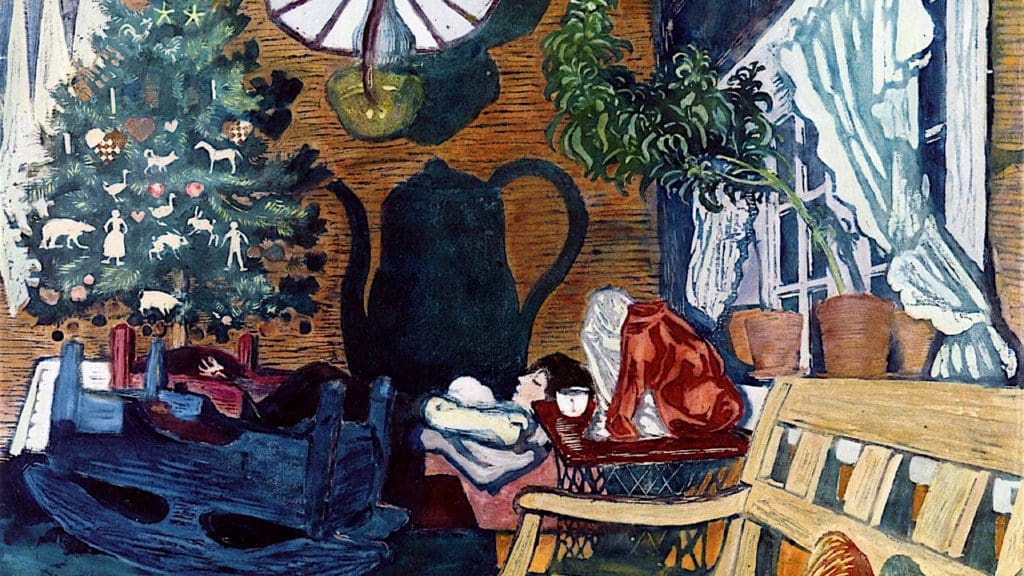

Advent may be Mary’s moment, but for many Christians, unfortunately, it is all she will get. As numerous publications and websites liberate Marian imagery from storage for the Advent season, we can expect the usual. Perhaps some Botticelli nativities or a Fra Angelico. Maybe that viral image of Mary consoling Eve. A Black Mary or two will certainly make the rounds, such as Our Lady of Ferguson. Maybe someone will branch into Marian imagery on offer in contemporary art galleries. (I’m partial to Tim Hawkinson’s response to Robert Gober.) This is all as it should be. The Mother of God deserves our celebration, even if it’s a shame that she may get packed away until this time next year. But of all the images of the Virgin, I doubt we will see too many Vierge ouvrantes, especially among Protestants. These images, the most famous of which survives at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, show Mary with the entire Trinity within her. It is rather odd to see not only Jesus gestating within her but in some cases a bearded God the Father as well. These unexpected Madonnas have been formally protested by Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestant Christians all (which is why there are so few of them left). She is hardly the Mary one expects, and many would prefer she stay packaged in the attic of Christian history where it seems she belongs.

The Pregnant Virgin from Németújvár, artist unknown, 1410.

But I think a case can be made for such images, even a Protestant case; and making it entails exploring one of the most exciting of medieval thinkers, to whom Protestants have as much of a claim as Catholics: the great late medieval mystic Meister Eckhart (ca. 1260–ca. 1328). In his headstrong youth, this Dominican friar’s aim was to surpass what Thomas Aquinas achieved, and most who knew him believed he had the intellectual acumen to succeed at his stated task. It was going to be called the Opus tripartitum, and it would offer a “universal metaphysics of Christian morality.” Part 1 of the three-part Opus was to contain double the content of the entire Summa theologiae by Aquinas.

But the Opus tripartitum, like Aquinas’s Summa itself, was never completed. In fact, most great intellectual projects aren’t finished (Coleridge’s Opus maximum and Barth’s Church Dogmatics, for instance). And in the case of Eckhart there is good reason to think we know why. In short, the mystical encounter that Thomas Aquinas had at the end of his career, the famous moment when he said, “Mihi videtur ut palea” (It seems that all I have written is as straw), appears to have happened in the middle of Eckhart’s career. And so, without denying Thomas Aquinas or giving in to the Oedipal rage to destroy one’s father, Eckhart turned to preaching to beguines (lay sisters) instead. He defended them from the same fate that befell Marguerite Porete, who was burned alive in 1310 for remarks such as “This Soul is saved by faith without works.” Preaching to nuns, ensconcing their mystical insights in the wider Christian tradition that he knew so well, seemed a more fruitful career path than competing to surpass the greatest minds of Christendom.

In his mystically learned sermons, Eckhart communicated a truth that is perfectly illustrated by the Vierge ouvrante, even in its boldest formulations including the entire Trinity, visualized Father and all. “When the will is so unified that it forms a Single One,” he explains, “then the heavenly Father bears his only Begotten Son in himself in me.” Eckhart’s declaration is the Trinitarian consequence of the famous evangelical imperative to “accept Jesus into your heart.” His homiletics offer a daring construal of St. Paul’s utterance that “Christ dwells by faith in your hearts” (Ephesians 3:17). Eckhart takes at face value Jesus’s prayer in John 17:21 that “they may all be one, just as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be in us.” As I’ve remarked elsewhere, the scandal of Christianity is not only that we should be born again but that God would be born again in us.

Eckhart summons us from premature Christmas sentimentality into mystical silence.

Of course, Eckhart is often suspected of being heterodox, but he ably defended himself against these accusations in his lifetime, and his more recent monastic brothers have done even better. As Benedictine monk and philosophy professor C.F. Kelley explained so lucidly a generation ago, Eckhart is not equating himself with the Trinity but instead looking at the mystery of the Trinity through the lens of “principial knowledge.” “All that we consider here externally in multiplicity,” he explains, “is there [in God] wholly within and identical.” Principial knowledge is a theological mode, also called “inverse analogy,” in which one imagines the world from the vantage of God, who can identify with creation while still being transcendent. “Eckhart never for an instant considers his proper self to be God,” explains Kelley. “It is the inverse of this that is implied when he says: ‘My innermost Self is God,’ or ‘My truest I is God.’” While most modern philosophy has failed to grasp this subtlety, as have Eckhart’s more casual New Age admirers, suffice it to say that Eckhart was in concord with Aquinas and was under no illusion that he was properly divine. On the contrary, he had overcome the illusion that anything could separate us from God—“neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation” (Romans 8:38–39).

Contrary to the cartoon versions of church history to which so many continue to cling, Eckhart has long been embraced by Protestants. Luther’s understanding of faith was underwritten by the Eckhartian mysticism on offer in Theologica Germanica (for which Luther wrote a preface). Eckhart’s ideas were also mediated through Lutherans like Valentin Weigel (1533–1588), Johann Arndt (1555–1621), and Jakob Böhme (1575–1624). It is the latter who mainstreamed Eckhart’s famous word for surrender, Gellasenheit, which is how the notion reached Anglicans like William Law (1686–1761) and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The Pietism that so shaped nascent evangelicalism was not unaffected by these developments. It should therefore come as no surprise that a world authority on Eckhart, Bernard McGinn, has recently argued how Protestants helped keep the mystical fires burning that modernity threatened to extinguish. McGinn is not alone in that estimation. Two recent edited volumes (Protestants and Mysticism in Reformation Europe and Mysticism and Reform, 1400–1750) obliterate the facile notion that there was no mysticism in Protestantism. Mysticism from the Protestant wing of Christ’s body is hardly surprising when one reads what the established mystics like St. John of the Cross actually say: “To be prepared for this divine union the intellect must be cleansed and emptied of everything . . . and supported by faith alone.” Even divinization, a doctrine once understood as the property of Orthodox Christians, has been unearthed among each of the main Protestant traditions. If it is clearer now that all Christians are called to be “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4), Protestants included, what better illustration of the Trinity dwelling within us could there be than the Vierge ouvrante?

When we surrender to the will of the Father, we too become Jesus’s mother.

As far as we know, Eckhart’s notion may have been inspired by such images, which were made in Germany when Eckhart was alive. Or possibly they were made out of response to his own sermons. But that is for the medievalists to debate. What matters far more is that it be realized in each of us now—instead of merely admiring Mary’s yes, to join in it by saying yes repeatedly to God ourselves. It is a well-known Protestant tactic, whenever Mary comes up, to cite Jesus’s words in Matthew 12:50, addressed to those trying to draw his attention to his family: “Whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother.” But to use that move to avoid a Marian theology is to jump from the frying pan into the fire. For if we read it plainly, the verse asks us to be Marian ourselves. When we surrender to the will of the Father, we too become Jesus’s mother, nurturing—through solitude and silence—the vulnerable presence of God within.

In sum, Eckhart’s ecumenical Marian theology is the opposite of spiritual voyeurism. We might prefer to watch Mary from the stands with two millennia of distance between us, and there is nothing wrong in principle with celebrating the singular mystery of Christ, born of a Virgin. But Eckhart also demands we suit up and take the field ourselves. He summons us from premature Christmas sentimentality into mystical silence, urging us to allow Christ to be born in us, not only in Advent, but throughout the year. “God wants nothing more of you,” Eckhart insists, “than for you to go out of yourself and all individuality and let God be God within.”

But nor should we show off about it. Instead, we close ourselves up, like a Vierge ouvrante statue, and tackle everyday mundanities, snow-shovelling and shopping, vacuuming and loading the dishwasher. All the while, like the glow that radiates from pregnant women, the light in our eyes betrays the secret within.