Editor’s Note: We’re accustomed to thinking of the practices of the Christian faith as something that happens within the church, shaping those who engage in them. But we don’t always think about what it looks like when those same practices translate into and affect public life, informing society beyond the church walls. Comment asked some writers to explore this question in reference to a number of the distinctive practices of the Christian faith—like tithing, prayer, preaching, baptism, and singing.

Previous in Series: Fasting

Next in Series: Discipline

Just before the dawn of the recording industry, popular songs were sold to the North American public in a format requiring of customers more musical literacy. When Let Me Call You Sweetheart and Down by the Old Mill Stream were published in 1910, their popularity was judged by sales of sheet music, and not yet by the records that would come into their own during the interwar years. Yes, people would attend performances of these songs by local bands and choirs, but they were more likely to gather round the upright piano at home and sing them together. People had to make their own music rather than rely on others to make it for them. Obviously not everyone had professional-quality voices, but that didn’t matter. Young and old alike sang their hearts out.

Although I was born well into the recording age, I grew up in a family that sang with gusto at the slightest provocation. We had two pianos in our house, and everyone played at least one musical instrument. We were raised on the old movie musicals by Rodgers and Hammerstein, Lerner and Loewe and, of course, Meredith Wilson, whose score for The Music Man harked back to that earlier era just before the outbreak of the Great War. In fact, so many times did we play The Music Man soundtrack that scratches eventually caused the record to skip. (If you were raised on CDs, ask your parents or grandparents what that means.) The notion of Julie Andrews breaking into song in the course of her day did not strike us as the least bit unusual.

Where did all this come from? Two factors seem to have been especially determinative of my family’s musical sensibilities.

First, we were avid church-goers. Some say that in our contemporary society, Christians are the only people who regularly sing together. When I first heard this observation some twenty-five years ago, I was astonished, but further reflection soon had me reluctantly agreeing. Where else do people join their voices together outside the walls of a church building?

In the 1983 film Educating Rita, Julie Walters’s character accompanies her husband to a typical English pub, where patrons are sitting round the table singing. Were this to happen in a bar in Toronto, the bouncers would likely move quickly to eject those responsible. Yet that same bar thinks nothing of having harsh recorded music forestalling comfortable conversation.

Perhaps Christians are indeed the last people to sing together regularly, but even we rarely do so outside of the worship service itself. Singing is simply not an integral part of our lives as it was for our forebears.

This brings me to the second factor. As the Soviet Union was in the process of breaking up more than two decades ago, citizens of the three Baltic republics of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia held massive rallies in favour of independence from the dying superpower. These were entirely peaceful, with no shouting of slogans. What participants did instead was to sing together in their tens of thousands in huge public squares. They sang the songs their mothers sang to them in the cradle, the songs they grew up singing while working and playing. Everyone knew these songs, because they were folk songs—no one in particular wrote them, but they covered the ordinary and extraordinary events in the people’s lives. It can truthfully be said that the Baltic peoples sang their way to freedom.

My family was heir to a similar tradition that largely originated in the Greek-speaking world. Ever since I can remember, we heard Greek folk music—on phonographs and 8-track players (ask your grandparents again), from my father’s lips, from the ubiquitous bouzouki bands that played at church festivals, and so forth. I acquired my father’s love of Romanian folk music as well, and in my elementary school years I gained an appreciation for American folk music (for example, Shenandoah and Michael Row Your Boat Ashore), which would lead me to take up the five-string banjo at age twelve.

These two factors have led me to the conclusion that there is an integral connection between liturgical and folk music, which distinguishes both from the commercial popular music that has drowned out our collective voice over the past century. Three common characteristics stand out.

First, both can be said to originate within a community rather than with an enterprising individual. No Susan Boyle has awaited discovery on the stage, cinema, or television. No recording contracts were ever contemplated, offered, or accepted. To be sure, someone must have sung There Is a Balm in Gilead for the first time—perhaps an unnamed African-American preacher in the antebellum South. From there the song caught on, perhaps in different forms as it moved from one local community to another, in a pattern similar to the differentiation of local dialects of the same language. The old spirituals obviously straddle the boundary between liturgy and folk song.

But what of the hymns of, say, Isaac Watts and Charles Wesley? To be sure, they were written by specific persons, as can be seen in the small print on the pages of any hymnbook. Nevertheless, Joy to the World and Rejoice, the Lord is King now belong to the larger Christian community, with worshippers paying little heed to their personal origins on a given Sunday morning. The same can be said of the Genevan Psalms, the Scottish Psalter of 1650, the German chorales and, of course, the truly anonymous Greek and Latin hymns of ancient times translated in the nineteenth century by John Mason Neale and others.

Second, neither liturgy nor folk music in its purest form has its roots in performance. This may not be obvious in a church dominated by trained choirs or worship bands. But the term liturgy in Greek literally means “public service,” or “work of the people.” Everyone gets involved. There is properly no audience in church—only a congregation of active worshippers.

Some traditions do not allow musical instruments in worship. While I believe this position is difficult to defend in the face of several explicit commands to the contrary in the Psalms (e.g., 149:3 and 150:3-5), there is nevertheless a haunting beauty in unaccompanied voices blending together in praise of God. The Orthodox Churches have worshipped without instrumental accompaniment for close to two millennia. Reformed Presbyterians have become marvellously skilled at singing a cappella in more recent centuries. Where instruments have been accepted, as in the Roman Catholic and Reformation churches, there is a strong preference for the organ, which, of all instruments, is said most closely to resemble the human voice. Where instruments begin to overpower the voice of the congregation, the line between the work of the people and passive hearing of a performance has been crossed (and this holds for both organs and praise bands).

Outside the gathered church, one of the few songs adult North Americans are likely to sing together is their national anthem, which often precedes sporting or civic events (that, and Take Me Out to the Ball Game during the traditional seventh-inning stretch). Yet even here, The Star-Spangled Banner has too wide a vocal range to be easily sung by many people and is often given over to a soloist at, say, Fenway Park or Yankee Stadium. Again performance takes away from the people.

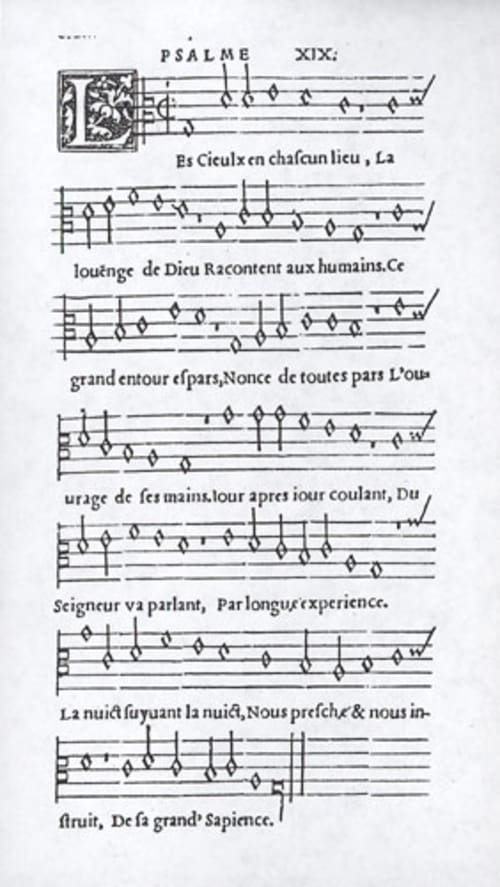

Third, both liturgical and folk music are modal in character, as opposed to the conventional major and minor scales, which we erroneously tend to see as exhausting our melodic possibilities. Without going into too much technical detail, the various modes are distinguished by playing a full scale starting on different notes of the white piano keys. The English folk song Scarborough Fair is in the Dorian mode, which means it can be played entirely on the white keys beginning at D. Similarly, She Moved Through the Fair and the Wexford Carol are both of Irish origin, start at G on the white keys, and are in the Mixolydian mode. It is no mere coincidence that British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, who did so much to reinvigorate English church music in the twentieth century, also drew on the modal tradition of folk music in such compositions as his English Folk Song Suite and Sea Songs. In Hungary, Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály collected the folk tunes of their native land in early recordings, arranging them so as to draw out their obvious modal flavour. Kodály also arranged several tunes of the Genevan Psalter, whose modal character suggests the influence of Gregorian chant on this sixteenth-century liturgical collection. Worshippers and folk singers alike seem intuitively to hear and make music modally.

A dozen years ago Robert Putnam published Bowling Alone, in which he argued that Americans are gradually losing the social capital that facilitates co-operation in a variety of venues. The decline of occasions for singing together is perhaps a symptom, and possibly even a contributing cause, of this loss. Could it be that we will reinvigorate our social and political culture by turning off our private mp3 players, pulling out the earphones, and joining our voices together in song? It might just be worth a try.