Dear America,

You have a memory and history problem.

As a political science professor, I am privy to the background and the foreground of the cultural moment as I live vicariously through the lives of my students—active consumers and budding culture makers that they are. My academic perch has taught me much about how Americans engage history, and even more about how well the most educated among them know American history. Here is what I’ve learned.

You, O United States, prefer to deal in the present and the future, avoiding the present vagaries of the past visited on those of us whose bodies, memories, and souls bear the stripes of your pyrrhic victories. Belated, anachronistic apologies for obvious American errors (forced migration, slavery, internment) bestow much angst on the remnants who survived history’s blows. The form of such apologies rarely looks like making amends, but rather tends to mimic the destructuralization and deinstitutionalization of the neoliberal politics of both left and right—favouring the claiming of personal culpability over collective responsibility for patently corporate ills. Individual apologies are performed to living representatives of history’s shame, which largely serve only to highlight the magnanimity of the apologizer. Irrelevant positions of inferior power are awarded to surviving stalwarts, intended to appease the gods for institutional inadequacies in advancing diversities and equalities.

The prevailing assumption in the way that your citizens tend to engage history is one of innocence, even in guilt.

The prevailing assumption in the way that your citizens tend to engage history is one of innocence, even in guilt. Settler colonialism in the name of civilization. War in the name of peace. Slavery in the name of political economy. Anti-miscegenation in the name of racial purity. Disenfranchisement in the name of good government. Clean were the hands and pure were the hearts that whipped my ancestors’ backs, chained their feet, busted up their families, experimented on their bodies, raped their women (with impunity), and ostensibly, built the republic, if we can keep it.

Educators and publishers at all levels sell histories that sanitize the reality of black enslaved women’s double labour as producers and reproducers, and scarcely see how this past reality translates to the tropes that trap me in 1854 or 1954 in your mind. If I am not the minstrel performing for you in the boardroom, the mammy mopping up your shit in the bathroom, or the magical negro fixing massah’ and missus’ problems instead of my own, you cannot place me. If I am at “the table,” you assume that I am there to serve you or to service you, if you notice me at all. You want to see no historical evil, hear less of it, and to defend your own words and works as racially righteous. Slavery has been defeated, segregation is past, and your beloved Union was saved and sanctified by the South’s sacrifice.

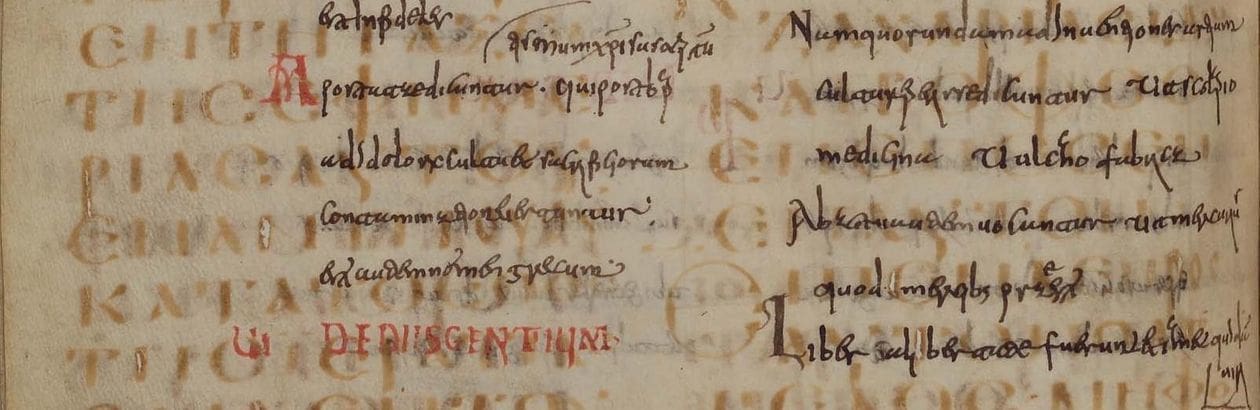

Take one example. Various Christian denominations tailored catechisms for their “property” to memorize and recite. This one was developed for enslaved Africans under the helm of Episcopalian masters:

Q. Who keeps the snakes and all bad things from hurting you?

A. God does.

Q. Who gave you a master and a mistress?

A. God gave them to me.

Q. Who says that you must obey them?

A. God says that I must.

Q. What book tells you these things?

A. The Bible.

Q. How does God do all his work?

A. He always does it right.

Q. Does God love to work?

A. Yes, God is always at work.

Q. Do the angels work?

A. Yes, they do what God tells them.

Q. Do they love to work?

A. Yes, they love to please God.

Q. What does God say about your work?

A. He that will not work shall not eat.

Q. Did Adam and Eve have to work?

A. Yes, they had to keep the garden.

Q. Was it hard to keep that garden?

A. No, it was very easy.

Q. What makes the crops so hard to grow now?

A. Sin makes it.

Q. What makes you lazy?

A. My wicked heart.

Q. How do you know your heart is wicked?

A. I feel it every day.

Q. Who teaches you so many wicked things?

A. The Devil.

Q. Must you let the Devil teach you?

A. No, I must not.

I felt the collective trauma of these tropes each time I heard citizen Trump call President Obama lazy for golfing while on summer vacation or a working trip. I experience personal trauma each time I hear my internal voice call myself lazy. Decolonizing my own mind is a lifelong project associated with post-traumatic slave syndrome.

Learning to Unlearn History

I was born on the other side of the American apartheid while its South African counterpart was still raging. At a young age, I was deemed an exception to the American exceptional view that blacks are lazy, unfit for life and godliness, and too untamed for the transactional space, capitalism, carved out by goody Calvinists’ arrival on heretofore “uncivilized” indigenous soil.

Everything I needed to know about race, religion, and democracy, I learned in kindergarten on a sunny April afternoon. Enter playground stage left, a tan-skinned black girl with long, silky, black braids draping down her shoulders, her head adorned with a crown of construction-paper feathers, her body bearing a faux buckskin dress, and her feet shod with moccasins (or more likely, ballet slippers). Action: she shifts and hops from one foot to the next, circling an imaginary firepit and making inchoate, high-pitched yells, cupping hand over mouth, and releasing the hand quickly and rhythmically.

The only black child in a sea of white faces, I was assigned to play the historical “other.” Already acutely aware of my otherness, I longed to be normal, like the other kids, who twirled in their prairie dresses or sauntered up to their place atop the covered wagon in their jeans, flannel shirts, and cowboy boots. My five-year-old mind perceived the zeitgeist: They were the main actors, and I a bit player—a mere asterisk to the re-creation of events deemed so central to Oklahoma history that we not only re-created them but also celebrated them. I was the conquered heathen, the perpetual underdog, the black stain on a white backdrop, destined forever to be typecast.

The re-enactment of the Oklahoma land run in which mini-me participated was not an ironic lament of the historical shenanigans whereby settler colonialists of the American West expropriated “No Man’s Land,” properly known as Indian Territory. Neither was it a ritual mass of belated lamentation for historical wrongs nor a precursor to reclamation for the indigenous and Natives of Oklahoma, red earth. It was a commemoration of expropriation. Squatters prancing and dancing on sacred, stolen land, with impunity.

Historical re-enactments proceed as though history has no valence. Historically oppressed Americans are actively encouraged to forget the past; to speak no more of the internment of Asian Americans; to wash our mouths with soap of the massacre of Wounded Knee; to stanch the wound of slavery once and for all. We’re told: Let history’s bygones be bygones; move on; there is more work to do for the capitalistic kingdom! But the wounds remain, and just as the outline of a scab appears, another body blow in the present rips it off.

“History is a great teacher” is a quote attributed to Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Rest assured that as a little girl, I internalized the lesson that my people’s tragedy is America’s triumph. “America,” your history has taught me one consistent lesson: the truth may set other folk free, but not me.

Memory in Black

My memory is a shade of obsidian, a black blot against a chalk-white historical backdrop. But I trust memory over history.

I trust memory over history.

I view memory and history not as a dialectic, like faith and doubt, sacred and secular, but rather as two warring, dissoluble factions, forever opposed, not as poles, but as enemies fighting for the souls of individuals and institutions, peoples and nations.

Caught in the whiplash of this ongoing battle, my mind filled with social studies’ saccharine portrayal of history as a series of unfortunate events, my memory haunted by the hushed horrors that the body recalls generations later.

My parents attempted to dispense the traumatic truth in age-appropriate bites. Nevertheless, my little old soul had already overheard the historical whispers and murmurs, had accidentally glimpsed Kunta Kinte while walking by the TV. I had already detected the pain in their eyes and decoded the meaning of the deep sighs. It was not good. My little black soul understood and whimpered silently for the pains we bore as a collective black body and as individual black bodies.

Primary school lessons bestowed on little Larycia a history of innocence. The white, Christian men and women who bid on black bodies were products of a political economy permissive of slavery because the Southern economy could not have survived otherwise. That tautological maneuver notwithstanding, I understood the implicit lesson: slave owners were innocents, victims of their own historical location, and furthermore, had I been atop the racial caste in antebellum America, I too would have wielded a whip.

Vacation Bible school and Sunday school catechized me into the knowledge of God’s creation; of good and evil; of humanity’s fall from grace; of the crimson stain of sin; of Jesus’s sacrifice to wash me white as snow. The pastor, who doubled as my grandfather, also preached of the prophets who preceded Jesus. They pressed evil empires to do justice to the oppressed. They pleaded with Pharaoh to release God’s people from slavery’s shackles. They sojourned on the outskirts and peripheries as prophets without honor, even in Podunk towns like Nazareth.

What I could not square as a child who took both social studies and Jesus seriously was how God-fearing folk who imposed their white-supremacist Jesus on enslaved Africans who already possessed varied and rich sacred traditions of their own could embody and codify such inhumanity. Jesus talkin’ ’bout good news. Didn’t my Lord deliver Daniel? Then why not deliver ol’ me?

Being black in the United States means honing a hermeneutic of suspicion as early as your first remembrance in order to counter the lies hurled your way by history.

Being black in the United States means learning that while God is always on your side and even prefers your oppressed position, the white folk posited by history as your people’s saviors were less mindful of your imago Dei than they were of their own legacy.

My people have survived these miserable histories—the multiple revisions of how shit went down, of who engineered what, for what purpose (white supremacy remains the latent answer), and who covered it up. Deep inside the marrow of our black memory, our bodies have retained the truth and borne epigenetic witness to the cost of the American empire’s active intransigence.

Chosen Amnesia

You, America, are pregnant with possibilities for reckoning with history, but there can be no absolution without confession. “America” would rather forget her ravages than reckon with them, but there can be no truth in reconciliation, no redemption of sins, without remembering.

The hegemonic national narrative subsumes the American rapacity for violence—racial, ethnic, economic, religious, sexual—in favour of selective histories. Western civilization is served on a silver platter as the corpus of knowledge. “Great Books” exclude entire civilizations and dynasties in favour of trajectories that culminate in how the West was won.

The truth is not elusive but seemingly subversive of American ideals, and thus most often buried like a needle in a haystack. To remember accurately would be to expose the mythos as just that. “Liberty and justice for all” has never been actualized because it was always reserved for the few by design. The meritocratic deck stacked on the backs of black folk like me. I still carry that load within my body and soul. But remembrance of this painful past, I am told, should be jettisoned in favour of forgetful-forgiving. Forgetting past sins is touted as the province of truly elevated souls.

Historical forgetfulness involves purposeful omissions and strange obsessions. Today’s rabid fascination with alternative histories is a symptom of this chosen amnesia. An entire television show was developed last year to explore the scenarios surrounding the question: What if the Confederate States of America, and slavery, remained and the Civil War had never been fought? Such exercises in hypothetical history are fun for showrunners to dream up and traumatic for those whose bodies bear the stripes of America’s original sin. Dixie dies hard in my home of Charlottesville, Virginia. There is no need to create an alternate historical one. I fight the Civil War everyday under the watchful eye of Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson statues.

Black folks are told that slavery is over and that we should move on from our history of victimhood. White folks flying the Confederate flag and hellbent on preserving statues that venerate treason are defending history. They can re-enact the bloody battle of Manassas, but they cannot bear hearing about the trauma double-helixed through my DNA. The immaculate conception of the City on a Hill trumps responsible remembrance.

Long Live Remembrance and Ritual

There’s something to remembrance, to rehearsing our past.

I do not speak of donning blue and gray to re-enact bloody battles waged to save a seditious, tyrannical secession of chattel slavery-saving aggression. Civil War re-enactments are passive-aggressive bodily paeans to white terror and violence. I do not speak of the hollow phrase “never again.”

Those of us in the category of “marginalized” or “minority” are not victims of history’s hand; we are survivors in spite of it.

What I speak of is embodied ritual, which rehearses pain from the past that lingers in the present. The litanies of the oppressed must be integral to our ritual practices as a nation. Their testimonies remind and rebuke America of the present consequences of past injustice and sensitize moral imaginations to see the shifting shape of injustice in the present. Only the perspective of the oppressed can speak to America so prophetically. Those that American history never considered legitimate consenters to the social contract are not convinced that we won’t be cast out, so we’ve developed a critical distance from the empire. I trust memory over history, especially in America, where bloody re-enactments that are the equivalent of Pontius Pilate’s washing his hands clean are preferable to the remembrance of communion.

That strange last command of Jesus to his followers: “Do this. In remembrance of me.” The command comes with the attendant consequence: “Unless you eat my body and drink my blood, you have no part of me.” The call to remember Jesus’s ordinary death on a tree and his extraordinary resurrection. A near cannibalistic feast rehearsing the past as often as possible with a view toward a future. A future unfulfilled without embodied remembrance of wrongs and a resolution to live forgiveness. Since the host of the table is God, the last is first and the first is last and none go away hungry or empty. Each filled to sate, contingent on their need—a table of equity, not equality, because remembrance of history matters.

By way of a crimson-stained cross and a eucharistic table piled high with the body of Christ, I cling to both memory and mystery. White death blows (those meted out by the visible hand of cruelty, as well as those meted out by the invisible hands of capitalism and caste) might sting, but they have no ultimate victory.

Politics, Prophets, and Hope

Is common memory possible where history lies fallow in the cotton fields of plantations that now double as choice vineyards for chic wedding venues? Can there be Jubilee when reclamation of land for the indigenous tribes and sovereign nations on whose land I squat fights to retain recognition from the American empire? Can there be Jubilee when reparation for enslavement of my own blood becomes a campaign issue precisely because it is a pipedream—a failed promise that is easily explainable by reference to politics as usual, a nothing burger?

Those of us in the category of “marginalized” or “minority” are not victims of history’s hand; we are survivors in spite of it. Civil War re-enactments without slave rebellions are dishonest. We look to the Nat Turners, the Fannie Lou Hamers, the John Browns, the Sojourner Truths. What belies the demands of powerful institutions and individuals for me to forget history? The fear of the loss of power unjustly attained at the barrel of guns, at the crack of whips, and at the redlining of maps. The fear of the collective power of remembrance to bring an empire to its knees. To remember would require reckoning with the monopoly of violence.

Of course, empire won’t save us. I am a political scientist, but my hope ain’t in politics. Much of what masquerades as politics is a futile sacrifice on an illusory altar. My hope ain’t built on a presidential candidate. Whitewashed tombs exist on all sides of the partisan and ideological spectrum. Just war is not just an oxymoron, it’s a political fiction. Politics is a false hope.

A hope based on remembrance understands that justice will not be accomplished with the aid of anemic history. The rocks will cry out for justice if we won’t; indeed, they are groaning now. How are we to hope while reckoning with the pain of memory and the bitter truth of history?

Hope must be informed by history because hope is always juxtaposed with memory of the thing hoped for—justice not achieved. The prophets of the Hebrew Scripture are archetypes of hope infused with memory and history. They see the writing on the wall because their memory is informed by the tragic. And yet, they hope.

Prophets are prescient. They’ve honed the eyes of their hearts to see injustice. But this is because they’ve done the body work and soul work and foot work to see injustice. They see people with the eyes of their hearts. They see people as vulnerable. And they imago-deify people. They wrestle with God in their hearts about injustice.

Prophets proclaim the truth. They can be reticent to do so, like Moses before Samuel before Jonah. Samuel had to share a difficult word of truth with Eli. But the truth eats away at them. The truth about the ravages of injustice are difficult when they indwell you. They are difficult words to share with family and friends. And this is why a prophet is without honour in her hometown. This is why Nathanael said, Can anything good come from Nazareth of Galilee? Prophetic words are unsettling. That God sees injustice is bad news for kingdoms and peoples content to discard the widow, the orphan, and the immigrant in favour of power for themselves.

Prophets are peripheral. And they put feet to faith. They go to the margins. Gandhi didn’t get lost and end up in the slums. Jesus didn’t accidentally go through Samaria. They hastened to the places of pariahs and lepers. Too many of us are content to be insiders—even self-congratulatory about arriving at the pinnacle of power. Prophets are not only exiled outside of the power centers, they prefer to be on the periphery with the oppressed.

The fire shut up in my bones blazes with a testimony as miraculous as Ezekiel’s graveyard.

Prophets are pessimistic. History is incomplete without bad news and good news. There is no good news about injustice. Injustice is all bad news. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. intones prophetic pessimism in his last book, Where do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? “Over the bleached bones and jumbled residues of numerous civilizations are written the pathetic words: ‘Too late.’”

There are no do-overs. Once released from their cargo holds, there was no recapturing the H-bombs released over Nagasaki and Hiroshima. While we are wont to ask, Do you want the good news first of the bad news first? prophets always lead with the bad news for a people and a nation hellbent on its own and others destruction. Prophets insist that we be enamoured of the dry bones. Only once they have made plain YHWH’s displeasure do they turn to hope.

Tragic Hope

What does responsible remembrance that leads to justice and reckoning require? It requires us to look to the historical other. The oppressed. The poor and the poor in spirit. The ones who rend their hearts and not their garments. Only a spirit humbled to the dust can do this work. Why? Because hope is always tragic.

The fire shut up in my bones blazes with a testimony as miraculous as Ezekiel’s graveyard. American history, even religion, may have robbed me and my people of many things, but not of memory. Ebenezers are passed down in code, through story, song, and stones of remembrance. That’s all some of us got. Freedom is a song and a pile of stones—tragic hope that the dry bones of our history can be resurrected in our memory.

Signed,

A Sister