I

In January of 2018, I took a plane to Albuquerque to sit in a hospital with my dying father. To say my dad and I weren’t close is an understatement: we had cut ties when I was twelve, and rebuilt them for a time in my early twenties only to have them quickly fall apart again. His life had since become a mystery to me. I knew, however, that heart problems had kept him in and out of the hospital for years, and despite several surgical interventions his health had long been in decline. So when the call came from S., his girlfriend of nearly two decades who hadn’t spoken to me since I was a preteen, I wasn’t exactly surprised. That she called at all meant things were serious. I took a brief leave from my obligations and packed my bags for New Mexico.

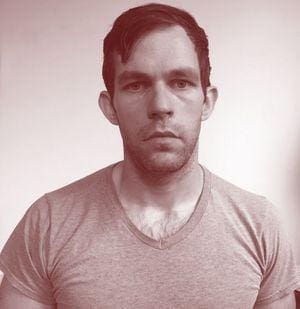

My dad was an interesting guy: a jazz musician (tenor sax, primarily, though he knew his way around the trumpet and flute) and an accomplished photographer. He was a very lapsed Catholic who, like my mother, had given up on the tradition of his family long before I was born. But out of a sense of duty he’d gotten us baptized and continued to bring us to the occasional Easter or Christmas Mass. He loved jokes—puns especially—and had a gift for charming strangers. He also had a history of heroin addiction, infidelity, conspiracism, and cruelty. My mother was his fourth wife. His first had fled his chaos for the safety of an asylum; the second left under quieter circumstances; he abandoned the third and their young daughter after a few years together. I don’t know how he hid his addiction from my mom for so long. But once she found out, she packed my brother in her Volkswagen Rabbit and fled their apartment in Washington, DC, for her father’s home in Memphis. Soon thereafter my dad kicked junk, followed her to Tennessee, and begged her to forgive him—and thankfully, for my sake at least, she did. He was never able, however, to leave his other demons behind. So after two more kids (and at least one lovechild) and another decade of enduring his philandering, abuse, and unnecessary jail time in contempt of traffic court, she packed my sister and me into a car and set off for Florida, leaving him behind for good.

So we’d long had a rocky relationship, and at some point in my mid-teens he became completely estranged. In the few years leading up to his death, though, my dad had made a seemingly earnest effort to reconnect with my sister, brother, and me. (Quite understandably, the other kids he’d left scattered around the country wanted nothing to do with him.) The effort quickly collapsed, and he developed an open, vicious hostility toward my siblings, inspiring them to cut their losses and sever ties completely. I remained the only one still willing to deal with him. But in the meantime, the fog of mystery settled back over his life—he was in Texas, he owned a home in Memphis, he was suddenly in Albuquerque—and I lost track of him for another year or two. Then the call came.

His heart had given him trouble for decades, but in 2017 his health took a catastrophic turn. He was only seventy-three—not young, but frail beyond his years. He’d long suffered from congestive heart failure, and when a major heart operation he underwent that spring failed to bring him back to full strength, he remained so sick and fragile that a fall he took in a hotel lobby landed him in the hospital for three weeks. He was left carrying around an oxygen tank and insisted that moving from the muddy, low river valley of Memphis to the high desert of Albuquerque had made his already difficult breathing even harder. His condition had been deteriorating rapidly, and after a few weeks of denial he finally agreed to be checked into the hospital again in hopes of getting patched up and sent back to Memphis, away from the high altitude.

This is where I found him, feeble and weary, surrounded by a jungle of tubes and beeping monitors, his broad shoulders and musician’s hands reduced to a skeletal parody of their former strength. Enough of a spark remained, however, to rekindle all the old family hostilities. My brother, in a burst of filial piety, began packing for the drive from Memphis to Albuquerque, but Dad refused to see him and demanded he not come. My sister, on the other hand, seemed almost happy to hear of his suffering: she said she felt nothing—no sadness, hatred, or pity—but her voice betrayed a whisper of excitement, as if she believed he was finally getting what he deserved. Dad didn’t care to talk to her either way.

I spent two days talking Dad into letting my siblings call him on the phone, to make one last connection before it became impossible. He finally agreed. During his brief call, my brother managed to achieve some peace: he told Dad that he loved him, and that he forgave him. His heart clearly wasn’t in it, but he did what he thought needed to be done. My sister, on the other hand, called only after Dad’s renal failure had left him unable to speak, and through a waterfall of tears she released decades of resentment on him. He was so debilitated that he likely couldn’t even understand what she was saying. But she said what she needed to say, and that was that.

After the paperwork got signed, cremation arrangements were made, and the poignancy of the shock began to dull, I began to wonder.

After three days by his side, I got Dad settled into a hospice facility and flew back to Maryland. He died two days later. I was devastated. But as the weeks passed, the sorrow began to fade, and those days and nights in Albuquerque opened themselves up for reflection. As a dutiful student of philosophy, I had long been habituated to using the stuff of experience as fodder for moral speculation. Runaway trolleys and imaginary axe murderers always struck me as ridiculous: if moral philosophy didn’t help make sense of life as one lives it—if it functioned only for deriving supposed laws from hypothetical edge cases—it was of no use to me. So after the paperwork got signed, cremation arrangements were made, and the poignancy of the shock began to dull, I began to wonder.

My siblings’ resentment of my father was, in a certain sense, entirely rational: he had harmed them immeasurably, often deliberately. This kind of treatment is impossible to bear from a stranger; how much more, then, when it comes from someone responsible for your very existence? It made perfect sense that the hurt they felt would beget anger. Why, then, couldn’t I shake the sense that this account, however reasonable, was wrong? There was some crucial principle we were all missing that could have helped us overcome our animosity and frustration toward one another, that could have granted some sense of unity to our fragmented family—something, I suspected, like forgiveness. We needed to find a way to forgive our father, and each other. So in order to figure out what forgiveness might mean, and what its origins might be, I turned—as I always do—to the books.

I began, as one does, at the beginning: in this case, with the beginning of Western literature, in the epics of Homer. Toward the end of the Iliad, after ten years of bloody battle between the Trojans and Achaeans, King Priam of Troy travels to the enemy encampment on the shore of his kingdom to beg for the return of his son Hector’s now-desecrated body. Priam is devastated by grief: he has lost his son, who was not just the bravest warrior of the Trojans but also a loving and devoted father, husband, and son. But so too is the Achaean prince Achilles, whose grief over the death of his brother in arms Patroclus led him to kill Hector, refuse him a proper burial, and ultimately to abuse his body by dragging it continuously around Patroclus’s funeral bier for nine consecutive days. Priam, guided by the god Hermes, sneaks into Achilles’s tent under cover of night and wakes Achilles by kissing his hands. As soon as he realizes what is happening, Achilles jolts awake, and Priam immediately makes a desperate plea for the return of his son’s corpse that concludes with an appeal to both pity and piety:

Honour then the gods, Achilles, and take pity upon me

remembering your father, yet I am still more pitiful;

I have gone through what no other mortal on earth has gone through;

I put my lips to the hands of the man who has killed my children.

What happens next is subtle but noteworthy:

So he spoke, and stirred in the other a passion of grieving

for his own father. He took the old man’s hand and pushed him

gently away, and the two remembered, as Priam sat huddled

at the feet of Achilleus and wept close for manslaughtering Hektor

and Achilleus wept now for his own father, now again

for Patroklos. The sound of their mourning moved in the house.

Achilles establishes distance from Priam, and the two men, sitting next to one another, weep privately—separately—for their own personal losses. They are alone together, sorrowing in solitude. This continues for some time. Finally, Achilles breaks the silence with a speech about fate and the irrelevance of human tears in swaying the decision-making of Zeus. The two agree on a temporary truce between their respective armies and an exchange of bodies; after the funerals, however, the hostilities will continue. Zeus deals out the fortunes of men, whether glorious or terrible; fate controls all, the slaughter must continue, reconciliation is an impossibility. Neither man could dream of crying for the other—mercy is unthinkable.

Here—deep in the bowels of enmity, each man trapped in his own sorrow—there is no forgiveness. In the Homeric universe, the foreclosure on forgiving is twofold. Achilles and Priam are made islands by their woe, the rocky shores of their souls admitting no landing. And a similar barrier rings their communities. All sympathy, empathy, and concern are confined within the limits of one’s political allegiance: the enemy is simply an enemy, not an object of mercy or even pity. It’s hard to know which hindrance has more priority. But both operate within families to destroy them from the inside, taking the form of the grudge: one personal and direct, the other through the cultivation of factions, but both privileging one’s own hurt over the well-being of another. And as in the Homeric portrayal, these varieties of familial enmity are taken to be natural and insurmountable. We are as we seem, and we seem destined for an endless cycle of hatred and anguish.

But Homer is a poet, a bard of the triumphs and failures of heroes. He’s not a philosopher—not the type to subject experience to questioning, to puzzle over the mysteries of life to inch closer to understanding. So I left him behind and looked to Aristotle and the later Hellenistic and Roman Stoics, our earliest examples of systematic ethical philosophy. Looking again to these writers I noticed a theme: forgiveness is understood in terms of withdrawing one’s anger from the other, and the arguments for it are by definition egoistic, concerned with the good only of the one who is doing this withdrawing. Here are a few examples.

In book 4 of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, the earliest written treatise on ethical philosophy, Aristotle describes a quality he calls megalopsychia, or “greatness of soul.” A great-souled person has acquired all the other virtues—wisdom, courage, temperance, generosity, and so forth—and has achieved thereby a nobility of spirit that sets them apart from others in their community. They have a sense of self-importance derived, Aristotle believes, from being genuinely more worthy than others: “If the great-souled person is in fact worthy of the greatest things, he will be best; for it is always the better person who is worthy of greater, and the best of what is greatest.” In this respect, they are the ultimate ethical exemplar, our living and breathing model for what a good life looks like.

The great of soul are marked by an attitude of lenience toward their inferiors, those of less nobility, stature, or virtue: “Nor does [the great-souled person] remember past wrongs; for great-souled people do not store things up, especially a memory of wrongs done them, but rather overlook them.”

But this great-souled person’s refusal to hold grudges is not a sign of compassion toward the less fortunate. Rather, this seeming charity toward others is simply a reflection of their own nobility of soul, a way to glorify their wealth of virtue. Because greatness of soul demands honour, here Aristotle segues into a discussion of the “virtue pertaining to honor,” which he calls being “good-tempered.” Here we see perhaps our clearest elaboration of forgiveness as simply a withdrawal of anger:

For being good-tempered means being unperturbed and not being carried away by one’s feelings but being angry in the way, in the circumstances, and for the length of time the correct prescription lays down; but he seems to err more towards deficiency, since the mild person tends not to look for revenge but rather to be lenient to them.

Aiming for an attitude of tolerant mildness seemed like the right direction: hot tempers are definitely a cause of familial entanglement in hostility and resentment, especially in mine. But tolerance, however mutual, is not enough to meet the demands that even functional families put on one another. Children can be irritating, even disappointing to their parents, and vice versa. The skill of forced leniency can and should be a part of a family toolkit, but a family member who feels merely tolerated by the others is scarcely in a position to flourish, and likely to feel hurt or resentful. And while status-based elitism might be helpful for giving structure to a city or country, it is unlikely to help a family: a son who wins great honours outside the walls of the home should still honour his father and mother.

A son who wins great honours outside the walls of the home should still honour his father and mother.

The Epicureans and Stoics had even less to offer than Aristotle. These philosophies are fundamentally therapeutic, set toward the ultimate goal of achieving ataraxia, or tranquility, a freedom from mental disturbances and physical pain. They are also explicitly egoistic, holding that the only actions with any moral significance occur in relation to oneself. Where Stoicism is entirely world-denying, holding that one’s moral disposition is the only thing of importance and happiness is ultimately a choice, Epicureanism is hedonistic, regarding physical pleasure as the highest good of human existence and urging moderation. In neither of these doctrines is there much room for moral duties toward others that don’t primarily entail the self.

Epictetus is perhaps the greatest articulator of Stoicism, and in his writing we see the egoistic dimension of Aristotle’s conception of virtue as the moral design of the self taken to its most extreme conclusion:

One who has had fever, even when it has left him, is not in the same condition of health as before, unless indeed his cure is complete. Something of the same sort is true also of diseases of the mind. Behind, there remains a legacy of traces and blisters: and unless these are effectually erased, subsequent blows on the same spot will produce no longer mere blisters, but sores. If you do not wish to be prone to anger, do not feed the habit; give it nothing which may tend its increase.

Anger is ultimately a decision: when we feel angry, we are deciding that anger is a good way to feel. And if anger is to be avoided, it is not out of concern for the well-being of others, but rather that anger destabilizes the proper functioning of the soul, which is to exercise its reason. Hostility, then, is wrong primarily because it is irrational, not because it is harmful to others. And because it is our duty as thinking beings to be maximally rational, we should avoid being angry.

Epicurus, on the other hand, left very little writing behind, and we receive his philosophy mostly by way of his disciple Lucretius. Though neither of them had much to say about forgiveness as such, here is Lucretius’s view of the attitude one should take toward the suffering of others:

It’s sweet, when winds blow wild on open seas,

to watch from land your neighbor’s vast travail,

not that men’s miseries bring us dear delight,

but that to see what ills we’re spared is sweet;

sweet, too, to watch the cruel contest of war

ranging the field when you need share no danger.

This doesn’t tell us much about forgiveness per se. But the implied attitudes toward the suffering of other people and the primacy of one’s own mental tranquility tells us, I think, all we need to know.

The consensus among the Greeks, it seemed, is that ethical activity is grounded in care toward one’s own soul. If forgiveness is morally valuable, it is because anger gums up the gears of one’s own flourishing and distracts one from more noble pursuits, such as engaging in politics, grasping for honours, or achieving spiritual equanimity. One might express concern for another if their spiritual greatness matches one’s own, if both parties are equally worthy of honour and praise. But concern for the good of another in full knowledge of all their flaws—even in their wretchedness—is alien to the Greek moral imagination.

Having been disappointed by Greece in my search for how to forgive, I turned my attention to the East. The Buddhist tradition endorses a similar understanding of the need for withdrawing one’s anger for the sake of one’s own spiritual health. Here we find echoed the doctrines of (1) the self as the principal object of ethical attention and (2) self-purification as the ultimate goal of reflection. Entanglements with the world and with others get in the way of the individual’s journey toward enlightenment. If one is to be lenient toward the wrongdoing of others, it is simply because the karmic order of the world demands this kind of flexibility in order to be properly maintained. Thus, we read in the Dhammapada:

-

- “He abused me, he struck me, he overpowered me, he robbed me.” Those who harbor such thoughts do not still their hatred.

- “He abused me, he struck me, he overpowered me, he robbed me.” Those who do not harbor such thoughts still their hatred.

- Hatred is never appeased by hatred in this world. By non-hatred alone is hatred appeased. This is a law eternal.

- There are those who do not realize that one day we all must die. But those who do realize this settle their quarrels.

The goal here is a kind of system equilibrium at both the level of the whole and the level of the individual ego. My goal is to make the world have less hate in it, but the only way to do this is to have less hate in me. The specificity and particularity of another person disappears altogether, subsumed into a system that one carefully maintains like a rock garden.

At this point in my studies, I felt exasperated. The only philosophical justification for forgiveness, it seemed, had to do with a reflective concern for one’s own condition, not for that of another. I complained to a friend—a devout Catholic—that my search for the philosophical origins of forgiveness had come to naught. I received a puzzled look in response. “You haven’t looked in the Bible?” he asked incredulously. All I could say was that it seemed too easy. I didn’t really know what I meant by this except that I had always been suspicious of Christianity as being somehow too good to be true, that it papered over the real ugliness of the world with a happy message about hope and love. As far as I could tell, we are alone in a universe that is slowly dying of its own accord, and all we can do in the meantime is stitch together beautiful stories of various kinds to build a shelter for ourselves from the cold indifference of the cosmos—but the indifference of the cosmos is what is real, not the stories we tell. Religion, I believed, is cowardice, retreat; courage demands facing the facts, owning up to the meaninglessness of things. And the central doctrines of Christianity, of course, are just so implausible: God and man at the same time? What could be crazier?

What I had found was a little hole in the structure of things, a place where human reason—even at its greatest and most noble—had been unable to go. And it was through this tiny gap that I first caught a glimpse of God.

But then my friend suggested the Gospel of St. Luke. If you’ve been raised in a Christian tradition, you probably take a familiarity with the Gospel stories for granted. My lack of religious education had meant that all I knew of Christianity was the Christmas story and a few other utterly decontextualized tropes: turn the other cheek, love your neighbour, do unto others as you would have them do to you. And though I had developed an interest in religious thinking as a complement to my studies of philosophy, I had never actually opened the book to see what was inside.

I didn’t immediately recognize the significance of what I read. After puzzling over Scripture for some time, I went back to my friend and reported that my mission had failed: I’d finally found evidence of forgiveness, but only in the Bible! What was I supposed to do with that? If the brilliant philosophers had overlooked something that only appeared later in the Gospels, troubling conclusions would follow. It would mean that our most important tool for discovering truths about the world had failed in one crucial respect—and if so, and we could not think our way to forgiveness on our own, it might have to come to us by some other route, arriving from somewhere outside of ourselves. Only after a few months of reflecting, and struggling, and fighting against the obvious like Jacob wrestling with the Angel, did I finally understand that what I had found was a little hole in the structure of things, a place where human reason—even at its greatest and most noble—had been unable to go. And it was through this tiny gap that I first caught a glimpse of God.

What I found in Luke was something completely new—something that as far as I can tell never comes up in the history of ethical thinking before the Gospels. The first comes in the passages following the Beatitudes, and is likely familiar to anyone reading this:

But to you who are listening I say: Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you. If someone slaps you on one cheek, turn to them the other also. If someone takes your coat, do not withhold your shirt from them. Give to everyone who asks you, and if anyone takes what belongs to you, do not demand it back.

The ancient philosophers of Greece, Rome, and the East were not stupid: they were some of the smartest, most perceptive, and thoughtful people who have ever walked on this planet. Aristotle invented logic; Epicurus was one of the first thinkers to suspect that the things we encounter in experience are actually made up of much smaller fundamental particles linked together in various ways. They observed the world with a remarkable keenness of vision, and the conclusions they’ve arrived at represent truly heroic attempts at comprehending the nature of human life using our natural ability to reason. Their thinking is good: they are right that it is good to avoid being angry, and to treat your own soul with kindness and care. And yet for each and every one of them, the idea that we should love our enemies would have registered as self-evidently absurd. They might insist that we avoid having our souls poisoned by grudges, but the idea that we should love people who harm us would be ridiculous to them.

Here, Christ tells us to love our enemies; later, he shows us what it means. In another passage in Luke, this time from Christ’s crucifixion:

When they came to the place that is called The Skull, they crucified Jesus there with the criminals, one on his right and one on his left. Then Jesus said, “Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.” And they cast lots to divide his clothing.

Again: “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you.” Hanging on the cross, in the process of being tortured and executed, Christ looks down onto the people responsible for his death and prays to God to forgive them. He is not ridding himself of anger to achieve spiritual tranquility; he is not trying to restore the karmic balance of the universe; he is not trying to showcase his own virtue. His concern, in the midst of his execution, is for the good of those who have wronged him. And it is entirely for their sake that he utters his prayer of forgiveness.

For each and every one of the ancient philosophers, the idea that we should love our enemies would have registered as self-evidently absurd.

As I said, however, it took time to notice all this. And when I did, I fought against it vociferously. I wanted to be a philosopher, not a Christian—I wanted to be one of those rare souls who courageously seeks understanding of our godless world, aided by nothing but reason and keenness of vision. Faith had never interested me, and beyond that I had no clue how to actually do such a thing as have faith. If God is truly personal and his love extends to each and every individual person, then prayer seemed like a part of it, and I found myself filled with the urge to pray for my father—but having absolutely no experience with the practice, I wasn’t sure where to begin. Given my dad’s putative Catholicism, I visited a local Catholic parish, hoping to catch someone who might help me figure out what I was doing. I haunted the rearmost pews like a ghost, trying my best to follow the movements of the liturgy and hoping my obvious cluelessness might be a signal to those charged with greeting newcomers. If anyone was so tasked, however, they never showed. In a chair near the entrance, hoping to catch a priest or some other kind and knowledgeable soul, I was met only by the backs of people hurrying to reach the sidewalk. After some days of this, I gave up.

Several months afterward, a former classmate of mine who had entered seminary was giving a guest homily at a local Episcopal parish. It was summertime by then, and I was renting a room in an unfamiliar house while finishing my thesis on Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, a book that had made a profound impact on my thinking and attitude. My thoughts, then, had been with the sea—its primordiality, its power, the mysteries of its depths. I had not been thinking much about God. I attended the service to support a friend; disappointments with churches in the intervening months had left me uninspired about Christian community. Immediately upon entry, I found their excessive welcome signage a bit too forced, their liberal politeness a bit too cloying. I didn’t sing the hymns; I wasn’t thrilled about being there. But then the readings began. God answering Job from the whirlwind, describing his laying the foundations of the world and setting a limit to the waters; Psalm 107, a call to God while sailing on a tumultuous ocean; Jesus, in Mark, stilling the raging sea; and the apostle Paul imploring me: “Now is the acceptable time, now is the day of salvation.”

I can’t remember exactly what I felt sitting in that pew—but I had heard, it seems, what I needed to hear. I stared at the floor for a while, “the problem of the universe”—in Melville’s terminology—“revolving in me.” But when the time came I stood, kneeled in the aisle, walked to the altar, and—“the body of Christ, the bread of heaven”—reached out my hands.

This essay—and some material in Keegin’s “Be Not Afraid,” at Breaking Ground—began as a presentation for the 2019 Lenten Program series at the Church of the Ascension, Chicago.