A

Abortion is an uncomfortable reality, for everyone. A great deal is at stake, and we know it. Rights. Duties. Lives. Whether we are on the periphery of an unexpected pregnancy or abortion loss, experiencing one of these ourselves, fighting for our view in the public square, or wearied by passionate arguments, we cannot escape abortion’s weight or pretend all is well. There are competing, deeply held visions of human flourishing when we consider abortion. No matter who we are, the world seems upside down.

Avail understands the predicament. For over twenty-six years, we have walked alongside more than eleven thousand women and men facing unexpected pregnancies and abortion loss. We have sat with them as they have felt stuck and hopeless in what feels like a zero-sum game. We have also had a front-row seat to miracles.

People are at the heart of any unexpected pregnancy, starting with the woman, man, and unborn child. But others are present too, through words, actions, or judgments: parents, relatives, friends, acquaintances, communities, even strangers who in some way represent the broader cultural ethos. The questions that swirl around the woman, man, and child tend to pit one person against another. The well-trodden paths of conversation involve demands for rights and pronouncements of duties. These complexities raise the stakes around any decisions to near intolerable levels of urgency and risk. Everyone is affected.

We need a new framework for the abortion conversation that provides hope and offers a way forward for all of us.

Our current landscape presumes inherent enmity between parties, but what if we start differently? What if we reject this assumption—instead of one another? What if we presume that each of us matters deeply and begin with a new question: What does it mean to love my neighbour?

Who Is My Neighbour?

In Luke 10, Jesus says that love of God and neighbour is the key to eternal life. Seeking to justify himself, the querying lawyer asks, “Who is my neighbour?”—and Jesus told a famous parable. A Jewish man had been beaten, robbed, and left for dead on the side of a road between Jerusalem and Jericho. A priest going down that road saw him and passed by on the other side. A Levite did the same. But a Samaritan saw him and had compassion on him, tending his wounds and leaving him in the care of others. This last man, the lawyer admits to Jesus, was the only one who acted as a neighbour toward the beaten Jew. “Go and do likewise,” Jesus tells him.

The invitation nested in the question, What does it mean to love my neighbour? is large enough for us all. What does it mean for me to love the pregnant, distraught neighbour in front of me—or her boyfriend or husband? And what does it mean for her to love me as I seek to help her? Or for each of us to love the tiny neighbour in her womb? What does it mean for us to love each other when we answer these questions very differently? These questions must precede any attempts to define and defend individual rights and duties or else we risk diminishing our shared humanity. We must recognize our humanity in our neighbour’s humanity, our story in his story, our future in her future. When we start with, What does it mean to love my neighbour? we reshape our lives toward the call to love in ways that show our willingness to help even at great personal cost.

We must recognize our humanity in our neighbour’s humanity, our story in his story, our future in her future.

Unexpected pregnancy makes us feel our vulnerability. We despise vulnerability because we can’t tolerate weakness. So we detach, maintaining self-righteous control to protect ourselves. We offer quick solutions and pat answers—whether to “get an abortion” or “carry to term”—that keep us from facing the reality that we too are often dependent, trapped, forsaken, powerless, and lost. Our lives are not all we might want or hope, and another person’s impossible situation reminds us that we do not have the power to avoid suffering and loss in our own lives. We so often turn to simple answers when what we really need is the courage to respond to the complexity of life with love.

Looking closer at Jesus’s parable to the lawyer shows us the true complexity behind the question, What does it mean to love my neighbour? The hero is a Samaritan, someone typically despised in Jewish society, and the victim was a fellow Jew. If the wounded man had been a Samaritan, the Levite and priest who walked by would have had moral authority to judge him, religious authority to avoid him, and social authority to reject him. But he was not. In telling the story this way, Jesus helped the man asking questions to see his own weakness—he was like the robbed, beaten Jew. At the same time, Jesus helped him see his inclination toward judgment and mercilessness—in the same situation, he too would have “passed by on the other side.” The lawyer’s need to have a neighbour exposes his vulnerability, and his failure to be a neighbour revealed his need for mercy. Jesus’s story helped the man consider a new, life-giving perspective.

At Avail, we believe that the moment we deny the perplexities and powerlessness of our own lives is the moment we have nothing to offer our clients. The first step toward meaningful connection with our clients is knowing we too are woundable. Avail’s advocates work with our clients shoulder to shoulder, approaching them as neighbours rather than overseers, because we all share in the same vulnerability of the human condition, and know the tenderness that it requires. We walk alongside, listen, acknowledge obstacles, and empower our neighbours to find solutions to the complexities they face. In this, we are vulnerable to grief, loss, and pain. But we are also witness to miraculous joy and hope in the lives of our neighbours.

Exuberant Joy

Emilia is one such neighbour. After moving to New York City to attend university, she began dating and eventually found out she was pregnant. Her boyfriend insisted on abortion. She wanted help to think clearly, so she looked online and found Avail. “I needed a safe haven to explore options and find support if I chose to parent,” she said. Emilia met with her client advocate more than fifty times, choosing to carry her pregnancy to term. “No one else was telling me I could do it. Avail helped me when I thought I wasn’t ready. They supported me when no one else did, and now I know I am not alone.”

Choosing to raise her son, Emilia took a leave of absence from her dream college. Her boyfriend became so abusive that Emilia moved out of their home and into a domestic-violence shelter. Avail walked alongside her through all of this. We helped her find secure housing with the Sisters of Life and connected her to regular practical companionship with the community at Safe Families. Emilia also enrolled in Avail’s parent education programs and received subsidized daycare through our Lend a Hand program after her son’s birth.

Shared joy and sorrow are made possible by the trust mutual vulnerability creates.

Her journey brought her more intimately into Christian community. One woman, Joy, heard Emilia’s story and sought out Emilia’s company because she had a son the same age as Emilia’s. She and several friends became advocates for Emilia, looking after her. They looked after Emilia’s son, hired her to babysit, helped her find affordable housing, navigated the city’s social-service systems with her, and coached her in job seeking. Through this all, Emilia and Joy’s friendship grew. They enjoyed simply hanging out, dreaming, even discussing the book of Mark. Joy says, “I was able to be there for her, especially during the years when she needed stability.” Now, years later, they have celebrated numerous birthdays and Christmases together. Emilia and her son found a home in the community.

Vulnerability makes room for our common humanity to be shared; it can erupt into exuberant joy in all of us.

We laugh a lot at Avail.

A Ministry of Tears

We share in vulnerability and joy—but that’s only a part of the equation. Sometimes vulnerability turns to suffering and being a neighbour means entering a ministry of tears. This was Julie’s story.

Julie was an international student applying for admission into prestigious law schools when she came to Avail. Her boyfriend had abandoned her, despite an earlier promise to marry her and raise the child they were expecting together. She was desperate for her family’s support—but instead faced their anger and threats. They said, “You will lose your whole family if you have this baby.” Nevertheless, Julie declared she would carry her baby to term. She learned the baby’s gender, had nicknames for her son, and gathered supplies to prepare for motherhood. Julie loved her unborn child.

Julie met often with Cindy, an Avail client advocate, and former Avail clients, one of whom had faced similar cultural pressures. She was surrounded by a new community of support. But over time, her family and cultural background broke her down. She told us, “I’m fighting; I’m doing everything I can to fight for this child,” but the fear of her family’s abandonment and the shame she’d bring on them for being a woman rejected by a man overwhelmed her. From overseas, Julie’s family hired a “nanny” to ensure she ended the pregnancy. Ultimately, this woman had to carry Julie into the abortion clinic.

Cindy started walking with Julie weeks before her unwanted abortion, and still walks with her. Both women have been changed by the experience. Cindy says, “Julie affected me, and still does. During her decision-making process, I struggled with powerlessness. . . . I was angry. I’m her advocate. My entire job is to fight for her for what she wants. I was angry at her parents and felt a strong tension, because Julie really wanted to carry to term. I am learning how to rest in God and trust him more.”

We cry a lot at Avail.

“But Who Is for Me?”

Shared joy and sorrow are made possible by the trust mutual vulnerability creates. In a world of cacophonous debate, women and men are asking, “But who is for me?” Avail answers, “We are.”

Leslie found Avail seven months after the birth of her first child. A thirty-three-year-old college graduate and paralegal working at a local firm in Manhattan, she found out she was pregnant again. She heard about the resources available to her, including Avail’s subsidized daycare, and initially wasn’t sure what she wanted to do. She had a decent-paying job with medical insurance and a partner of many years. But soon she decided her relationship with the father was too unstable and the risks to her physical well-being after a complicated first delivery too unknown. Abortion seemed to her the best choice. Within twenty-four hours she made her decision, booked an appointment, and got the abortion.

Her advocate recalls, “She was in a tough situation. Her boyfriend was really uncaring. He was unapologetically unfaithful and did not provide any financial support.” Leslie told no one but Avail about her pregnancy and abortion. Two days after her initial visit with an Avail advocate, she trusted us again and came back to talk, processing her decision with Avail for the next two weeks.

That wasn’t the last time Leslie honoured us with her trust. Months passed without any contact with Avail, until one day Leslie reached out seeking solutions to her financial stress. In particular, she wanted to inquire about support from Avail’s in-house daycare subsidy program. She remembered hearing about it when she came to discuss her unexpected pregnancy. With help from her client advocate, Leslie applied to receive support from state programs for child care, but her income was just high enough to make her ineligible—yet still low enough that she could not afford both rent and daycare for her now ten-month-old son. Normally, clients who receive Avail’s daycare subsidy are active clients who decided to parent. Though Leslie’s request was unusual, the Avail team decided that the only response was a definite yes. “This program is not a reward for a client carrying to term,” affirmed one staff person. Avail is called to love unconditionally.

Your Story Is My Story

The Samaritan encountered the man dying in a ditch as he walked the dangerous road between Jerusalem and Jericho. A priest and Levite happened upon the man too. The Samaritan stopped and helped, but the priest and Levite did not—rather, they intentionally avoided him. The priest and Levite said, “We have our own stories, and they do not include you,” whereas the Samaritan said, “Your story is my story, and my story is your story.”

This is why the question, “Who is my neighbour?” is so uncomfortable. It reveals that we have a common story we cannot ignore, a responsibility to others that compels action. This genuine love for our neighbour always comes at a personal cost. At his own cost, the Samaritan tended the man and invited a nearby hotel owner into this care. The Samaritan helped meet the man’s physical needs and engaged him in other supportive relationships. The priest and Levite chose the appearance of virtue—scrupulous adherence to rights and duties—but in reality had simply deserted their neighbour, unwilling to pay the price of true love.

Jesus’s question to the lawyer—“Which of these three, do you think, proved to be a neighbour to the man who fell among the robbers?”—is at the heart of the abortion debate. It reveals a weight of complexity for all of us. Loving your neighbour—and setting aside self-righteousness and judgmentalism—is a messy, complicated business. It asks more of us than others. This is the terrain that Avail walks every day.

People are sometimes tempted to say, simplistically, “The woman just has to see that the neighbour is the baby!” But our work at Avail shows that we must see and love the woman as our neighbour first, or she cannot be empowered to see the baby as her neighbour.

Ultimately the passion on all sides of the current abortion debate indicates how much people care for all those affected by an unexpected pregnancy. But the challenge of loving our neighbours well often tempts us to try to control others’ wills to shape them to what we think is best. What if to become better neighbours, we started by asking more of ourselves, not more of others? This would mean leaning into the requirements of our own worldview, not looking at others’ failure to live up to their own.

The challenge of loving our neighbours well often tempts us to try to control others’ wills to shape them to what we think is best. What if to become better neighbours, we started by asking more of ourselves, not more of others?

If we do this, we will come together to make a measurable difference in people’s lives, people like Emilia and Julie and Leslie. We might even discover a deep well of mercy for ourselves, like the lawyer did. All of our flourishing—women, men, children, the entire community—depends on this.

Our clients usually come to us believing abortion is their best or only choice, and we don’t lecture or refuse to deal honestly with their mounting pressures. We commit ourselves to understanding our clients according to their worldviews, serving them according to their complex needs, and caring for them no matter what decision they make. If we fail to respect our neighbours despite any differences, why should they trust us? But if we embrace the vulnerability of being a faithful presence, a guide and not someone who seeks to control, then we can earn trust. As we seek to love our neighbours as ourselves, seeing the image of God in all whom we encounter, we empower women and men to gain access to communities and solutions where pressures are often alleviated—allowing them to love and care for their unborn child. Each year, 68 to 78 percent of Avail’s reporting clients change their minds and carry their pregnancies to term.

Sometimes the failure of community support and related complexity is so great that even the woman who wants to see a way forward with her child feels she can’t—whether from external pressures or internal expectations—and she tragically terminates.

Abortion is a symptom of complex human suffering and sin. It shows that sin happens on many levels, individually and collectively, and that none can escape it. Responsibility is both personal and corporate. In any situation, there are often multiple victims and perpetrators . . . and sometimes one person is both. These choices and tragedies are as old as time. But until the final act of Christian redemptive history when all things are made new, we participate in that beautiful story from which all stories derive their meaning every time we affirm, as Desmond Tutu has reminded us, “I am, because you are.”

Mercy Triumphs

The Christian story is one of hope. When all seems lost with no way forward, God does the unexpected—he makes streams flow in the desert, rough places plain, and even dead bones come to life.

After Julie’s tragic abortion, she wanted to bury her son. She asked the abortion clinic for her son’s remains, and with the Sisters of Life, she memorialized her son’s life. The Sisters covered her in mercy.

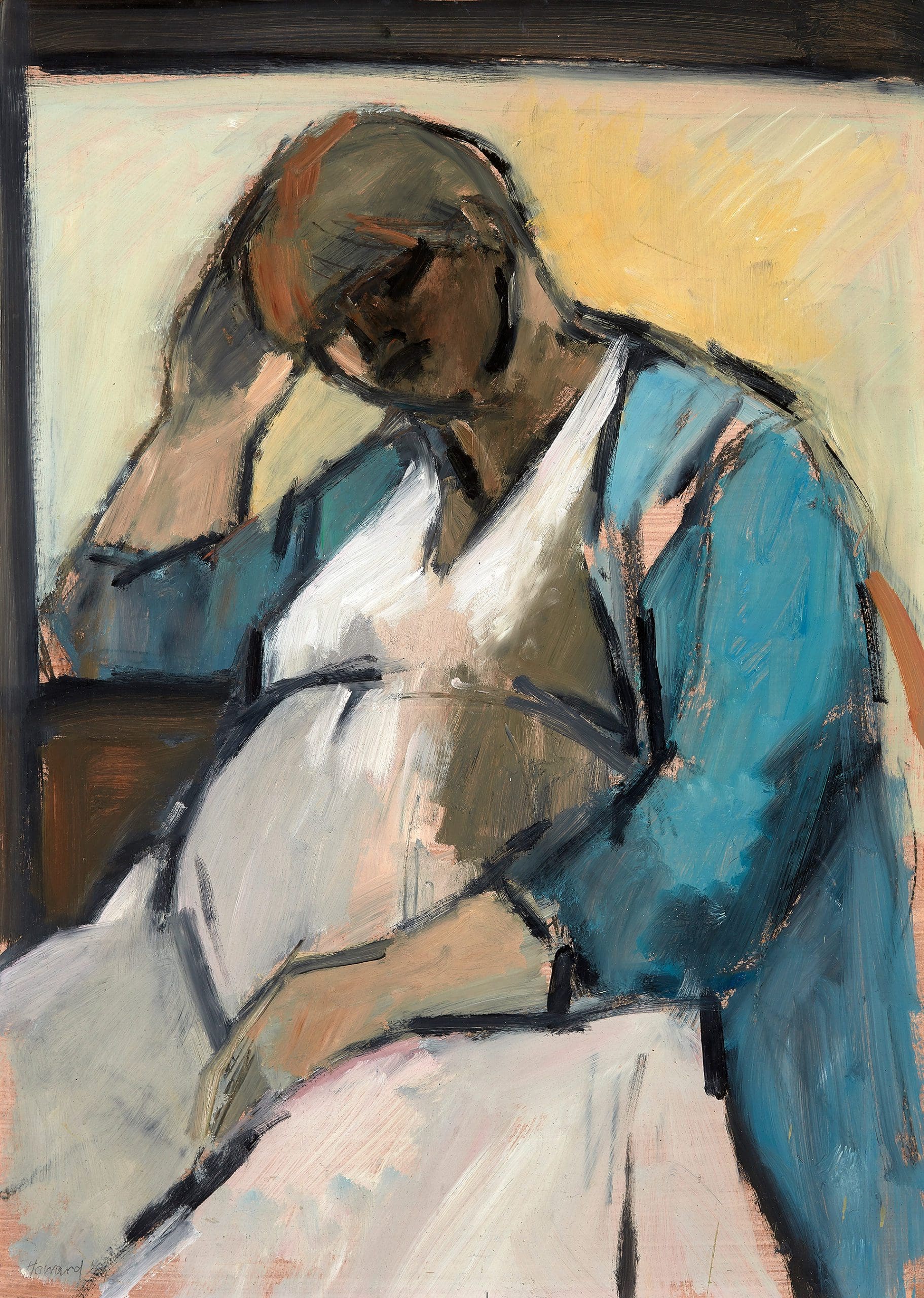

It wasn’t long before Julie started covering others in mercy. To cope with her grief, she began engaging online with pregnant women facing challenges. She sent maternity clothes to some and encouraged others to escape abusive relationships. For one woman experiencing a terrible loss like hers, she created a painting of Jesus holding a baby—her baby, her friend’s baby.

Julie was just starting to learn about Jesus when she created this painting. Yet God gave her the image of the Saviour cradling her lost infant. It’s a picture of redemption, death becoming life, something irreparably broken being made whole.

When all seems lost with no way forward, God does the unexpected—he makes streams flow in the desert, rough places plain, and even dead bones come to life.

One day Julie was in Washington, DC, and she walked into a church for the first time in her life. Unbeknownst to her, it was National Infant Loss Day. The sermon addressed the story of David’s mourning and other Bible stories about people experiencing God’s comfort through loss. The message touched her deeply. Since then, Julie is coming to understand better who Jesus is. It brings her great comfort to know that her child is safe with God.

Hope is not pretending everything is okay. Neither does hope moralize in the face of suffering or minimize complexity to persuade. Sometimes the choice is truly between what is bad and what is worse.

Hope is confidence in things unseen. Hope is an assurance that we are beloved by God no matter what, that mercy triumphs over judgment.

Abandoned on a lonely, dangerous road, the broken Jew had no reason to hope anyone would help him, especially not after two religious men walked away. But when the Samaritan stopped and invested in his well-being, they were bound together in a new future defined by mercy. As the lawyer listened to Jesus’s parable, he too was drawn into a new future. He had never considered a view of himself that put him out of mercy’s reach, and he found himself understanding the heart of the law for the first time: love.

Julie’s relationship with her family is not yet restored. She grieves the loss of her son. But as Julie has told Cindy, “If Jesus forgives everyone in the world . . . if he can forgive everyone’s sin and hurt, then I can forgive my parents and ex-partner.”

Because we know all things will be made new when Christ returns, we do not need to despair when this life disappoints, even shocks us. There’s hope because our stories are not yet over; God redeems. We can join Cindy in saying, “I can’t believe I get to be a part of this, to watch God do this in this woman’s life.” And in our lives too.