Near the end of his seminal New Yorker article “The Hot Spotters,” Atul Gawande recounts a story about Dr. Jeff Brenner, a physician who has pioneered efforts to help some of the most costly and difficult patients in the hospitals of Camden, New Jersey. During a community meeting at an apartment building that had been identified as a “hot spot” (frequently sending its residents to the ER), Brenner’s coalition put up some numbers for everyone to see: People in the building had received an average of sixty thousand dollars’ worth of care in ER visits and hospital stays over the past five years. When confronted with this figure, people were astounded. None of them could comprehend that such a sum had been spent—and no one felt like they were sixty thousand dollars healthier.

From every perspective, this story illustrates a problem both widespread and pernicious in the U.S. health-care system, though the problems are not absent in the Canadian and U.K. systems either. Many patients can recount hospitalizations where they spent much money but walked out with the same symptoms. Every doctor can tell you about services they have performed and documented to meet billing criteria they knew would have no effect on their patients’ health. The widespread overuse of health-care services doesn’t just waste money, though—it also puts more people at risk of being harmed by overtesting and overtreatment. Simultaneously, there are many people whose early death or disability could be but are not prevented—either because they don’t have access to lifesaving care or because they engage in unhealthy behaviours that are undeterred by frequent hospitalizations.

Vast sums of money are spent on behalf of patients every day, but the power such money represents usually bypasses the powerless. There is incredible potential both for better health outcomes and more community empowerment, but in order to accomplish these the health-care system must democratize primary care and shift the power from centralized government bureaus and massive health-care institutions to the communities where the sick live. There must also be a commensurate shift in the locus of health-behaviour change from offices and hospitals to homes and streets. While disassembling the current system will be very challenging because of the entrenched ways of distributing funds and power, we must view health as stewardship of all the resources available to us. And we must bring the resources (and power) within our patients and their communities to bear if we expect them to be healthy.

The Power of Communities

Where does all the money in Gawande’s example (and similar communities) come from, and where does it go? In the United States, for patients who have Medicaid and Medicare (the poor and the retired), hospitals generally go through an arcane series of negotiations with the state or another insurance company that manages the state’s money and use the payments they get for medications, lab testing, equipment, and salaries of support staff and health-care professionals who ostensibly address the health concerns of these patients before discharging them (though often not very effectively, as many come back to the ER dozens of times per year). Patients get interviewed, scanned, medicated, and advised—frequently with a negligible impact on their overall health.

Both patients and doctors feel trapped by the current system, which is well-suited to treat acute and life-threatening illnesses but has not adapted to adequately deal with chronic diseases. This dynamic is more prominent in emergency rooms and hospitals, but is also present in outpatient offices. Hypertension and depression are just as life-threatening as heart attacks or cancer, but take their toll much more slowly and are less responsive to the power doctors can exert. The tests and treatments now ordered—primarily based on those things that can be more “scientifically” measured and dispensed—form the hammers that define the nails health-care practitioners see everywhere. Diet, exercise, work, and social relationships have far more to do with cardiovascular health than cholesterol medication (it is estimated that unwise health behaviours are responsible for 30–50 percent of early deaths), but you can’t put exercise in a pill and make a billion dollars.

Frequently ensconced in beautiful but inaccessible hospitals and clinics, doctors feel like they have difficulty communicating with their patients in the fifteen minutes or fewer they’re allotted for visits and have neither the time nor the cultural intimacy to help patients make the changes that will lead to better health. Doctors then get frustrated when “noncompliant” patients won’t “do what they’re told,” but can’t imagine any tools besides the ones they already have because the existing payment systems and power structures have hemmed them in. Similarly, patients often feel like their doctors are hard to get ahold of and then feel rushed when they do get their fifteen minutes together. The advice doctors toss out—eat healthier, exercise, quit smoking—is easy to agree to in the exam room, but much harder to live out back home. One of my residency colleagues was perplexed when one of her patients would only eat prepared foods despite his desire not to be massively obese, but then quickly realized his predicament when she visited his apartment and found roaches in every corner!

All the while, doctors constantly feel financial pressure to stay busier (quite often to pay off hundreds of thousands of dollars in educational debt), and the current payment system provides a greater incentive to document properly in the electronic medical record than to have a conversation with their patients. Any service the hospital or clinic cannot bill for is tacitly considered a nice extra, if one has time to implement it, and anything a doctor could be sued for is forbidden. (One community health researcher told me that he found lay health educators and family members far more useful to work with because nurses were constantly constrained in simple tasks like filling pill boxes according to state regulations.) Clinicians understand the records themselves as clearly designed for the purposes of billing rather than for recording important information about patients, reflecting how perversely funding structures and licensing requirements have shaped—and continue to shape—the structures of our health systems.

Many attempts to force higher-quality interactions between patients and medical institutions are ham-fisted and rarely seem to produce the outcomes intended. For example, every nonprofit hospital is required to have a system in place to ensure that there is a “community benefit” from the hospital’s work, and new Affordable Care Act rules require a “community health needs assessment.” However, a recent article in the Stanford Social Innovation Review had to point out that a useful feature of evaluating a community includes spending time “with people from the community they are evaluating”! Such an “innovative” suggestion implies that community health still has a very long way to go in many places. Moreover, the class gap between doctors and their patients is exacerbated by the physical distance between where each lives.

The community—the homes and neighbourhoods where people live, work, and play—holds great untapped potential for improving the health of individuals. After all, it is in these places that any one person or family makes the individual, day-to-day decisions that constitute health: whether to smoke another cigarette or take one’s prescribed medication, whether to order a pizza or make a salad, whether to sit alone with the television or go for a walk with a friend. It’s no surprise, then, that the latest mantra in health recognizes that one’s zip code is more important than one’s genetic code. Two neighbourhoods just a few miles apart in Baltimore, for example, have a twenty-year difference in their respective life expectancies. Any smart doctor recognizes that the fifteen minutes a patient gets with them every three months is no match for the culture and environment a patient will return to; thus we doctors spend most of our preventive visits trying to elucidate which cultural and environmental factors have the most power over our patients and brainstorming ways the patient can exert power in their own lives.

Power, Behaviour, and Choice Architecture

The unhealthiest communities with the lowest life expectancies and the most health problems often have two strikes against them: they have little power over most of the environmental factors that contribute to health (or, more often, its detriment), and many of their internal predispositions toward poor health are deeply ingrained adaptations to the other challenges poverty brings.

In the first case, for example, the relatively low access to healthy, fresh food and the overwhelming accessibility of tobacco, alcohol, and drugs in urban neighbourhoods like mine are undoubtedly the result of businesses targeting these places for decades to sell certain products that make people sicker. Such efforts have helped to create generations for whom such products and the illnesses they foster are normative. Between this sociocultural inertia and the additional infrastructure required to stock and sell healthy food (e.g., refrigeration), there is little incentive for businesses to offer such food. If my neighbours have to choose between hiring a taxi to buy a tomato or walking down the street for a bag of chips, they’re incentivized to choose the latter. If my patients have to choose between waiting six weeks to schedule an appointment with a therapist to deal with their panic attacks and buying a Xanax from a friend, they’ll probably keep buying the Xanax until they can’t anymore.

In the second case, as I try to treat obesity, respiratory diseases, and substance abuse in my work at a clinic for the homeless in Baltimore, it is impossible to ignore the fact that the stress, depression, and anxiety generated by a life stuck in poverty are powerfully (albeit temporarily) alleviated by unhealthy food, smoking, and drugs.

Thus the lack of options within physical environments and the ingrained responses resulting from poverty become a lack of power that creates a culture of bad decisions. The capital and the government services necessary to alter these physical environments that affect health, disability, and longevity have been concentrated beyond the reach of these communities and their members. A good job is often very empowering (and for older people, it is often motivation to stay healthy), but when labour with a decent wage is an hour’s bus ride away, the power that such labour could bring is diminished. It is fair enough to suggest, as most liberals do, that the government provide more to the poor in the way of housing, food, and health care. What troubles me about this suggestion is that such programs—at least the way they’ve played out in places like West Baltimore—are usually wealth transfers from taxpayers via the government to absentee landlords, low-quality corner stores, and low-performing hospitals. The power bypasses the people.

The gravitational pull of poverty, then, is so strong that some of the most effective antipoverty programs involve displacing families, moving them into a different jurisdiction altogether. Such strategies, however, never ask how to change the power balance within these areas of concentrated poverty. This reflects a shallow understanding of poverty that sees it only as a lack of stuff, which can be remedied by giving poor people more stuff. However, in their book When Helping Hurts, Steven Corbett and Brian Fikkert point out that when you talk to poor people, they’re far more likely to mention “shame, inferiority, powerlessness, humiliation, fear, hopelessness, depression, social isolation, and voicelessness.” Additional resources are part and parcel of this—if you can’t pay for your asthma inhaler, you’re going to feel powerless—but until our fundamental commitment to addressing health disparities through community health is focused on restoring power to the powerless, we will continue to see the institutions of the powerful buttressed with tax dollars, leading to uncertain outcomes for the poor people they are supposedly helping.

This power dynamic can (and must) be altered.

The Limits of Politics

Most conservative solutions to America’s health-care crisis—when they get beyond “repeal Obamacare”—are too anaemic to be useful because they fail to address the opacity and wastefulness of the insurance industry. (For example, U.S. medical practices spend nearly four times as much as Canadian ones do on interacting with insurers.) The most promising decentralized proposal, Direct Primary Care, merits serious consideration for its desire to make relationships central to health care but still sacralizes the physician without truly democratizing primary care. (It also doesn’t answer the thorny question of how best to pay for the medications and lab testing that many chronically ill patients have difficulty affording.)

By contrast, liberal proposals beyond the Affordable Care Act generally focus on single-payer funding and access to treatment for all. Such access is crucial, but access guarantees neither responsibility nor the power needed to exercise responsibility. A great many patients who are still very sick and die young have had excellent health coverage through Medicaid for a long time. Conservative talking points about the relative value of Medicaid are generally off base (as many studies demonstrate that being on Medicaid is far better population-wide than not having any insurance), even as they often miss the fact that Medicaid (and Medicare) are massive subsidies to an industry that is only incentivized to provide better health care when the government threatens to withhold portions of it. The kernel of truth in these critiques, however, is that cultivating health in our bodies requires far more than health care. While a single-payer system would undoubtedly reduce bureaucratic waste and prevent death and disability in people who don’t have access now, opening the floodgates of access without fundamentally altering how we think about and deliver health care runs the risk of making the system even more unsustainably expensive and exposing more patients to the risk of overtreatment.

Health care cannot be divorced from politics because ultimately every government is interested in protecting the bodily integrity of its citizens. The challenge is that any top-down solution (e.g., cigarette taxes or a vaccine mandate) is far easier than creating conditions under which bodies thrive, but it’s just as easy to restrict freedoms or create unintended consequences. Conservatives often overstate the limits of politics in promoting health by underestimating how often the powerful abuse freedom to the detriment of health (such as in pollution and workplace safety). Liberals, by contrast, tend to underappreciate such limits when they assume that a top-down solution is invariably the best one.

Health-care markets work tremendously well for elective procedures; leaving chronic-disease management or emergency care solely to the vagaries of supply and demand is willfully ignorant. The places where the government should most strongly apply its often indiscriminate heft should be limited to preventing and treating the most life-threatening illnesses as well as the projects that give the most power back to individuals and their communities over their diseases.

Health Is Stewardship

What would a more democratic, empowering system look like? Foundationally, it would be based on the understanding that health is stewardship of all available resources, individual and institutional. It would maximize the power and utility of any health-care worker so that no one’s training would be put to waste doing tasks that someone else could do. It would use statistics to judge the effectiveness of different programs, but it would not constrain itself to such numerical assessments; a holistic approach to promoting health requires more than numbers to be considered successful. It would see any area of human life as open to intervention, but always ask what the least intrusive intervention would be.

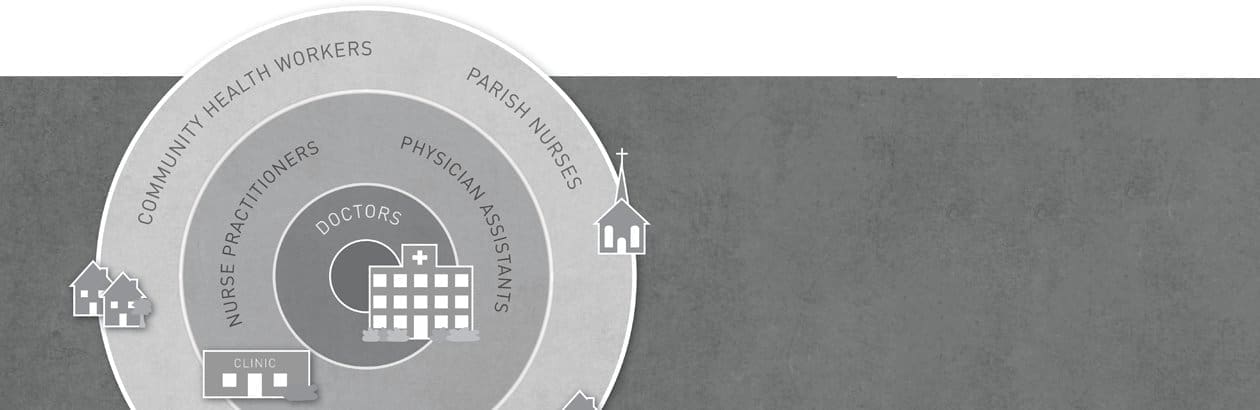

The first practical change we should pursue is directing the bulk of primary preventive care away from physicians’ offices and into the realm of community health workers (hereafter CHWs). The only benefit of the annual checkup by a primary-care provider is that it establishes a relationship with someone you can then trust if another health crisis emerges. It is a waste of time and money to pay physicians, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners to order flu shots and tell patients to eat healthier—both of which are often crucial elements of a typical annual checkup but don’t need to be tied to a physician. But that that’s how our current reimbursement practices work. The administration of universally applicable evidence-based treatments and counselling for a healthier lifestyle should be given to CHWs who come from the communities they serve, possess some sort of training that focuses on how to help individuals choose healthy behaviours as a part of public health, and control a budget for health-promotion initiatives in the community.

CHWs or nurses could also just as easily engage in secondary treatment of common chronic diseases and acute treatment of common maladies. One does not need a medical degree to prescribe a single blood-pressure medication or assure someone their cold doesn’t need antibiotics. As long as clear guidelines about what these health workers can and can’t do are followed, with anything that deviates from the protocol immediately kicked up to a higher level of care, a great deal of health care can be made more culturally, geographically, and financially accessible to patients for a lower cost.

These community-based health-care workers should be explicitly encouraged to work with other institutions in the community that “have a strong tradition of caring for others and that attract people who identify with this tradition,” as Richard Bennett and W. Daniel Hale put it in their book Building Healthy Communities through Medical-Religious Partnerships. They go on to point out that religious institutions not only fit this description perfectly but also have the added benefit of being uniquely suited to helping minority populations, many of whom suffer from worse health conditions. If we fear the encroachment of government regulation on one side and the poison of industrial agriculture on the other, explicitly favouring CHWs may be the best way to give the people more power to fight back against both.

If we lay the foundation of primary preventive care and the simplest of some chronic care in the community, more highly trained providers in bigger health-care institutions can focus on caring for sicker and more complex patients. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners are often just as good as physicians at providing many services; current regulations unnecessarily restrict them in many ways (like not being allowed to prescribe Suboxone for addiction treatment). Since they are already the frontline workers seeing acutely ill patients in emergency rooms, urgent-care centres, and hospital wards, these roles should be formalized and expanded such that physicians wouldn’t need to supervise their care unless something beyond their scope of practice or knowledge arose. There should also be an emphasis on their local nature, encouraging reciprocal relationships between mid-level providers and CHWs so they can collaborate and share information when patients get admitted to the hospital or go back to their homes.

Such collaboration would also be crucial for social workers and case managers (some of whom would hopefully also be able to release some of their usual duties to CHWs). Physicians would be involved with very sick or very complex patients, ideally in institutions that are rooted within the community or partnered with these local organizations of CHWs. Having had extensive and expensive training, physicians should apply their skills to problems that lower-level providers are less capable of while helping to oversee community-health efforts or provide input to CHWs on the technical aspects of their work.

Payment for services beyond what CHWs provide could simply be taken care of by a single-payer system, but they don’t necessarily have to be. At the very least, catastrophic care should be guaranteed for all, along with a basic list of essential medications (similar to what the Veterans Administration provides). People who wish to pay for insurance to cover everything in between—imaging studies, other medications, specialist visits, acute hospitalizations—can do so, although it would likely be far easier to let a transparent market emerge for these services that allows patients to shop around for the price and quality they prefer. People too poor to participate in such a market could have subsidized health savings accounts (HSAs) that could be used not just for medical services but for any health-related costs. For example, someone with diabetes trying to lose weight may want to purchase a gym membership, or a family whose child has recurrent asthma could use an HSA to pay for duct cleaning. One might even be able to imagine a whole community contributing a portion of their HSA together for a new community pool or startup costs for a farmer’s market.

A complete overhaul of our current health-care system isn’t necessary for churches and other intermediary institutions to help their communities and take hold of power that currently belongs to more aloof and far-flung entities. Many health-care organizations, realizing how limited their current infrastructure is, are looking for community partners who can assertively define how and where they can do a better job at cultivating health. Grants are another useful option for testing new ideas and building stronger community institutions; Lawndale Christian Health Center in Chicago is a great example of an organization that has sought to build as much as they can for the people in the neighbourhood, with tremendous success. Bennett and Hale’s previously mentioned book lays out a number of suggestions that any church could implement with or without such funding or partnerships, and their office in a Baltimore hospital has for years supported a lay educator program that partners resident physicians from the hospital with active community members to engage churches about crucial health issues facing their congregations.

The overall focus must and should always be in giving people more power over their own health, with the expectation that self-determining power—particularly when mediated through local institutions—is more effective at helping people take care of their bodies than being told what to do by larger and more distant institutions. The individual balances between state and citizen can be haggled out, but the current system—even if it moves to completely guarantee access for all—is still too top-heavy to meet the needs of individuals and the communities their bodies inhabit and interact with. Stewarding health in this way answers our call to steward creation, tending to and caring for our neighbours, who bear God’s image. Such work is integral to the justice and healing for which creation—and all too often, our neighbour—groans.