I

If you go to an elite conference or event of the Aspen ilk, you will hear steady, even relentless talk about non-profits. Non-profits are seen as a major vehicle for social change, in many cases the primary vehicle. It is common for attendees at such convenings to sit on the boards of non-profits, to become major donors, or even to found non-profits. Non-profits end up becoming part of a personal portfolio, a calling card, and a source of personal reputation, both as a hobby and as a passion. Many people will talk about their non-profits more than their actual line of work, and this is especially true for the high-net-wealth coastal elite.

Exactly when and how did non-profits become the assumed vehicle for social change?

Some of this development is simple peer pressure. If high-net-wealth coastal elites donate their money and time to non-profits, surely they must be important. The mainstream media helps cement this image. Ever seen the “How to Spend It” section of the Financial Times, or comparable supplements from the Wall Street Journal or the New York Times? Though most media figures are not high net wealth and have little to do with non-profits, they are pandering to the high-net-wealth crowd. So if the high-net-wealth crowd has a psychological bias toward non-profits, both elite and mainstream media will track and reinforce that trend.

These biases deserve to be challenged. Just how important are non-profits really? I think we still don’t know, and I have been involved with non-profits my entire life.

Exactly when and how did non-profits become the assumed vehicle for social change?

I would like to set out some alternative, stylized theories of social change with an eye toward putting non-profits into a broader social context. What are some of the broader factors determining whether we should assume non-profits to be a major vehicle for social change?

I will consider three theories in turn: the economists’ theory, the religion theory, and the television theory. I treat each of these as “ideal types”—that is, they are rarely held in pure form by any single individual. Most people will hold some composite of these views, but we can better understand them by considering them in their starkest terms.

The Economists’ Theory

Economists believe that for-profit firms, in the process of responding to consumer demand, are a central vehicle for social change. Human welfare increases when entrepreneurs innovate and create new ideas to benefit consumers. A nation then moves from an inferior equilibrium to a better equilibrium, with the essentials of that process being driven by commerce but with government and rule of law in the background.

If I think of my life improvements over the last twenty years, many of them stem directly from commerce. I have easy access to almost any book through Amazon, I chat with my friends over WhatsApp, I enjoy superior dining opportunities with regional Chinese cuisine, and the cars I can buy keep on getting better, even if only marginally.

And what have non-profits done for me as a consumer or user, putting aside the ones I work at—namely, George Mason University and the Mercatus Center? That is harder to say. They might have helped with my health care, except I haven’t been sick. They have contributed to the social fabric in ways I don’t always see directly. Without non-profits, perhaps my community would be more fractious and less generous and the streets would be dirtier. Maybe! But that is not as easy to see as an Amazon package left on the doorstep. Churches I will consider later.

So on the surface, the economists’ view does not seem absurd.

The economists’ view leaves room for government to be a major force for social change and economic improvement. If the government institutes congestion pricing, for instance, as it has done on Route 66 in my neighbourhood, it is much easier for me to drive home in the late afternoon. The greater mobility complements the commercial forces discussed above. If I can pay an extra three dollars and access the highway without a major traffic jam, I am more likely to take an afternoon trip to the shopping mall, or to stay later at work.

Even when government changes course, much of the real action occurs through the decentralized private response to the new policies. For instance, if congestion pricing is introduced, the actual change in the world is still brought about by the private-sector response. In this regard, the role of government in the economic model of social change is a kind of handmaiden to self-seeking and for-profit motivations and activities.

In the economic approach, non-profits have a very definite role, but it sounds a little underwhelming. Theory suggests that there are some “trust goods” that markets cannot provide very well. For instance, if you wish to donate to higher education, you might not trust a for-profit institution to husband your funds in the appropriate manner. Trust in this regard is much higher in (some) non-profits, and so all the major American universities are organized as non-profits. Charities typically are non-profits as well.

In the American economy in 2016, about 1.44 percent of GDP was donated to non-profits. That is not an exact economic measure of their relative social import, but it is a starting point for seeing their secondary role in the economic model.

Furthermore, microeconomics directs our attention to the fact that a lot of non-profits are not vehicles for social change at all, but rather opportunities for tax arbitrage. Do all those hospitals really need to be non-profits? Aren’t they just regular companies that managed to procure a tax exemption? Most of them make money, above and beyond any donations they might receive, and they are not always so kind when it comes to treating the indigent. From an economic point of view, it could be said that a fair percentage of America’s non-profits are phony non-profits of a sort. In these cases, the non-profit isn’t a major vehicle for social change; rather, it is a bunch of profit-seeking vehicles with a tax break, masquerading as non-profits. That makes the contribution of “true non-profits” smaller yet.

In my various jobs I mentor many younger people, who often ask for career advice. If a young person tells me they want to do something commercial, I do not try to persuade them to do non-profit work instead. In some cases, though not a majority, I try to talk individuals out of their non-profit plans and urge them to at least consider the for-profit sector. I tell them that non-profits can be less glamorous and more routine than it seems, that most of them do not in fact succeed in helping the world, and that they are becoming ever more bureaucratic. This advice, which is sincere, reflects my belief in the import and greater dynamism of the for-profit world. In this regard, Tyler the human being and Tyler the economist are pretty closely allied.

The Religion Theory

Religious belief is a central driving force behind social change, far more significant than non-profits. But in the United States churches typically are non-profit institutions, and in this sense religion generally can be considered as part of the non-profit sector for our purposes. Nonetheless, churches are very special non-profits, attached to the production of religious ideas, rituals, and social gatherings. Religions are thus special in a way that, say, March of Dimes is not. Again, I am setting up an “ideal type,” probably not held very often in its extreme, stand-alone form.

Arguably, religion sets the tone for the entire set of ideas in society. Most Western societies have predominantly Christian heritages, and this is reflected in their histories, their holidays and social customs, and most importantly their underlying codes of morality. Christian societies rate relatively high on individualism and share to some extent a common sense of charity and mercy. Christian societies are more likely to be stably democratic, although the lines of causation here are murky. Capitalism has blossomed in many Christian societies. In this regard, the religion model might try to subsume the economists’ model as a special case, with religious ideas being fundamental to the foundations of a market economy as well as to the broader constitutional order.

In the United States, the role of churches remains quantitatively significant. One 2016 study estimated that faith-based organizations have yearly revenues around $378 billion. That number might be lower today as a result of ongoing secularization and perhaps lingering COVID issues, but still that shows a good deal of commitment and possibly influence. In 2016 that sum was about 60 percent of media and entertainment industries, and about half of what all restaurants earned.

The notion of religion and churches being so fundamental persists in America today, most of all with churchgoers. Yet the hypothesis is especially unpopular among the coastal intelligentsia that has elevated non-profits to such a driving force behind social change. Most of those individuals are secular, or if they are religious, they usually prefer to present a secular face to maintain their status among the elite. So these individuals will attach to their non-profits, and promote them, in a way that they will not attach to their churches, temples, mosques, and synagogues. The relationship of American Jews to their synagogues might be a partial exception, but even then many of these individuals are secular in their intellectual orientation, and their attachment to Judaism is more cultural, familial, and historical than theological per se.

In the religion theory, non-profits can be seen as a partial substitute for religion and its social functions. Just as religions once gave people a sense of purpose and belonging, and for that matter collected donations, non-profits serve the same roles today. Furthermore, if past religiosity was a means of signalling virtue (whether accurately or not), arguably the same is true for non-profit support today. It is no accident that so many major donations are accompanied by “naming opportunities,” such as when a building or an academic school is named after the giving individual.

In one view, you can think of non-profits as the inferior substitute for religion, never filling the spiritual voids that may be left in our hearts. Can a non-profit really have the depth and all-encompassing nature of a religion and religious worldview? We are making do with something worse. Perhaps with the non-profit we are sometimes doing more good on some broad issues such as public health but doing less for our communities.

From another point of view, the non-profit is actually a superior and modernized competitor to religion, and largely a successful competitor. The non-profit sector has been growing, but church life is shrinking in most wealthy countries, including the United States. Perhaps religious outlooks are too all-encompassing, too demanding, and involve social ties with too many others in a manner that is too constraining. (Going to church every Sunday is harder than a yearly board meeting.) There are many more non-profits than religious denominations, so religions in this manner may not offer enough choice. Non-profits may be “religion lite,” but perhaps religion lite is what we want and all we can handle. Many non-profits also seem better suited to a country with falling birth rates, rising rates of single-parent families, and a rising status for women, since many of the major religions encourage childbearing, two-parent families, and some degree of sexual inegalitarianism. The non-profit is capable of reversing those status markers, at least superficially. And common stereotype has it that many non-profits are predominantly staffed by highly educated women with a relatively small number of children, or women who are single at above-average rates.

As an economist, and a secular one at that, I find it difficult to evaluate the religion hypothesis. Nonetheless, at the very least I see it as one way of taking non-profits down yet another notch, because religion is yet another social institution that seems to have more impact.

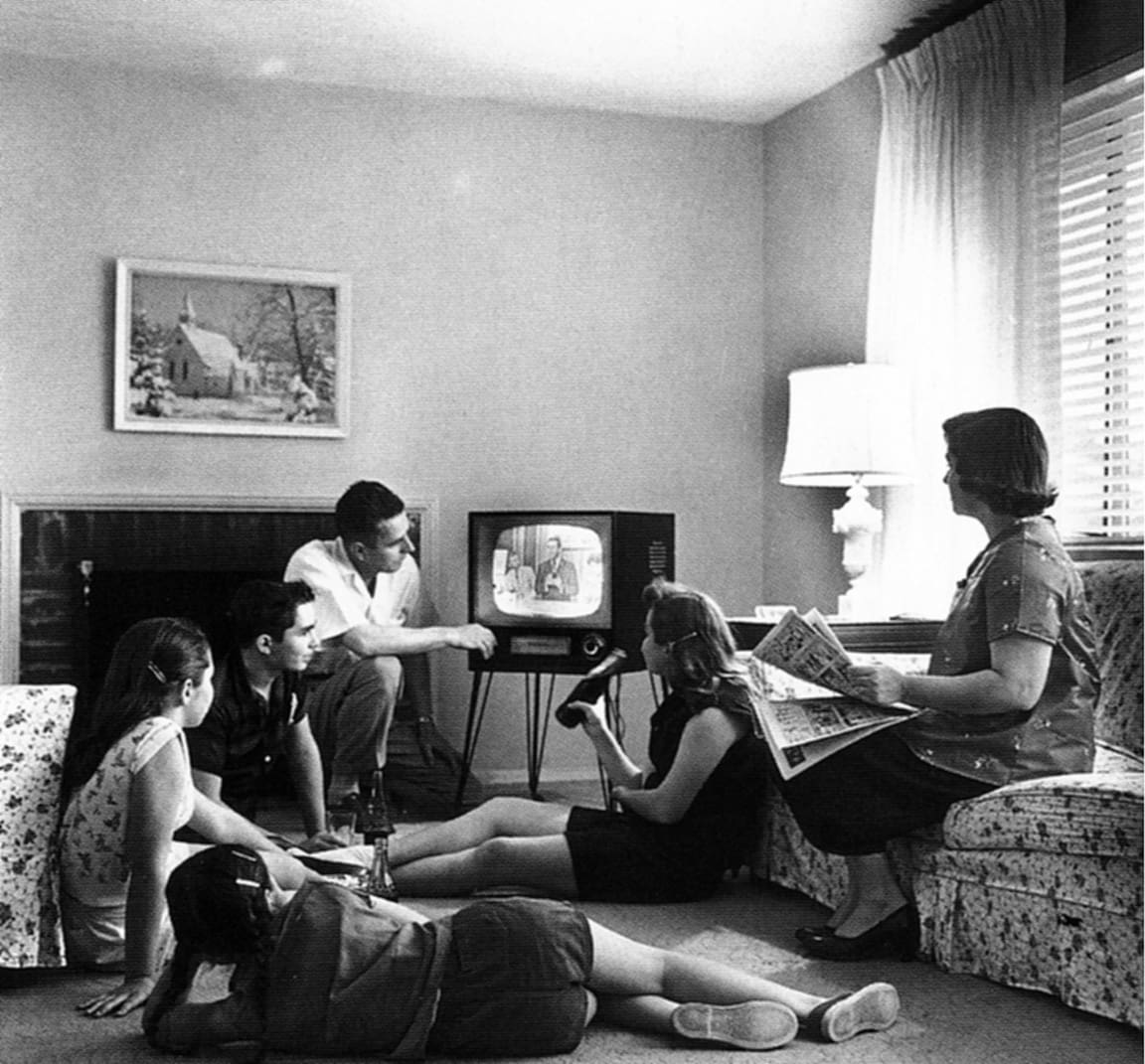

The Television (and Social Media) Theory

For short I’ll call this model “the television theory,” noting that other media can play a big role, depending on the years under consideration. Arguably, Donald Trump is an advocate of the television theory—namely, that what is on television truly matters and influences the American public on a mass scale. Radio might matter too, and more recently social media have risen in importance. In this view it is television and other media that measure which ideas are brought before us. Religion may have a background role, but most change, including religious change, happens in the media. Mainstream media is a small percentage of measured GDP, but its influence is disproportionate to its share in the broader economy.

Since most of these media are for-profit, you might consider this a subset of the economists’ view. But it adds two important components to the argument. First, ideas and visuals are needed to drive the import of the for-profit sector. Second, television and other media help make an idea’s growing importance common knowledge, which is necessary to spread the idea further. Once I realize that everyone is talking about a given topic, I need to inform myself about that topic. Some topics thus end up what is called “above the line,” and the media discourse on those topics can drive changes in public opinion, including in the sphere of religion.

In the television theory, non-profits may play an important role in seeding ideas into the media. For instance, effective altruism received a great deal of media coverage in the summer and fall of 2022, in part because of William MacAskill’s new book on the topic and in part because Elon Musk tweeted in support of the idea and the book. Yet many of the ideas behind effective altruism came from universities, whether in the form of Peter Singer, Oxford University, or the Center for Effective Altruism. Non-profits thus can serve as a kind of research-and-development lab for the media sector, which on its own is not always superbly innovative in its thinking. So non-profits re-emerge as having a significant role, but not the one that their advocates and promoters typically envision.

Putting It All Together

Once you put these accounts of social change on the table, you can see that each has some force, noting that opinions on their relative influence will vary. If we return to our central question—When did non-profits become the assumed vehicle for social change?—the word “assumed” seems to take on greater importance than before.

Religion and its role in American life created an underlying intellectual and ideological framework of “service” that non-religious non-profits were able to slot themselves into.

The most likely answer to the question is that incentives from media and the for-profit sector of the economy combine to elevate the status of non-profits in a particular way, most of all to elevate the status of elites. This hypothesis is consistent with the view that non-profits are beneficial and benevolent, but at the same time we ought to view their current status as largely the result of self-interested motives—motives that play out through a very specific political and institutional context.

Religion does not feed into this process directly in the same manner that commerce and media do, as religion is in some ways a competitor with (non-religious) non-profit organizations. Nonetheless, religion and its role in American life created an underlying intellectual and ideological framework of “service” that non-religious non-profits were able to slot themselves into. The history of religion in America thus led to an underlying infrastructure for the later expansion of non-profits.

When did this all happen? I would submit that the religious component dates back to the seventeenth century and the origins of American Protestantism. The histories of radio and television are long-standing, but their import for this question was elevated with the rise of a more significant inequality of wealth, which I date to the early 1980s. The more money there is to give away, the more importance non-profits will have and the more publicity they will receive. Not coincidentally, the 1980s also saw an extreme elevation of American celebrity culture, and so now an article about the Gates Foundation, in addition to its other roles, is also an article about celebrity. Finally, the import of social media in this whole process is quite recent. If I had to pick a year, I might say 2012 marked the beginning of the social media era. After that point, actions taken by celebrity-affiliated non-profits would be dissected endlessly on Twitter and elsewhere.

So when it comes to the elevation of non-profits, there are some very old pieces of the puzzle (American religion), some pieces of middling age (radio and television), and some very recent pieces (social media). The wealth inequality starting in the 1980s was a key driver of how all these pieces came together in a more intensified form in recent decades.

I do not expect this edifice to be dismantled anytime soon, and it may spread globally, most of all to burgeoning capitalist economies such as India. If anything, the already inflated social status of non-profits might rise even a bit more than is probably deserved. As those global economies develop, the forces driving their growth will sooner strengthen than disappear.