I have a lot of sympathy for Christians in public life. When you do political or public work, you inevitably end up rubbing shoulders with folks who don’t believe the same things you do. You make friends with atheists, agnostics, Muslims, Jews and others; you begin to see the fine work they do and the very excellent people they often are. This is more than merely the problem of religious pluralism—it is the inevitable outcome of doing public life rightly.

What I mean by “doing public life rightly” is closely tied to what theologians and philosophers call common grace. Common grace recognizes that God’s favour works on both the saved and the unsaved. It’s a framework to help us understand how the unsaved, apart from the specific saving knowledge of Jesus Christ, can produce and sustain acts of mercy, justice and beauty. And it is a framework that helps us see people as more than targets for Bible tracts. We become interested in them as people whose mixed passions and desires intermingle with our own, and whose company and conversation we come to enjoy and to miss when it is absent. We inhabit not merely their intellectual, but also their moral and emotional horizons. We respect and even love them. This means we take what they say seriously, value it deeply and allow them also to get to know us in ways that can be uncomfortably vulnerable.

Common grace suggests a radical openness to people who are not like us, and it poses two big questions. First, how can we have this kind of radical openness to people and still be rooted in the traditions of the Christian faith? Second, how can we work deeply in the systems and processes of North American public life—with its saturations of material wealth and power—and still be people of integrity?

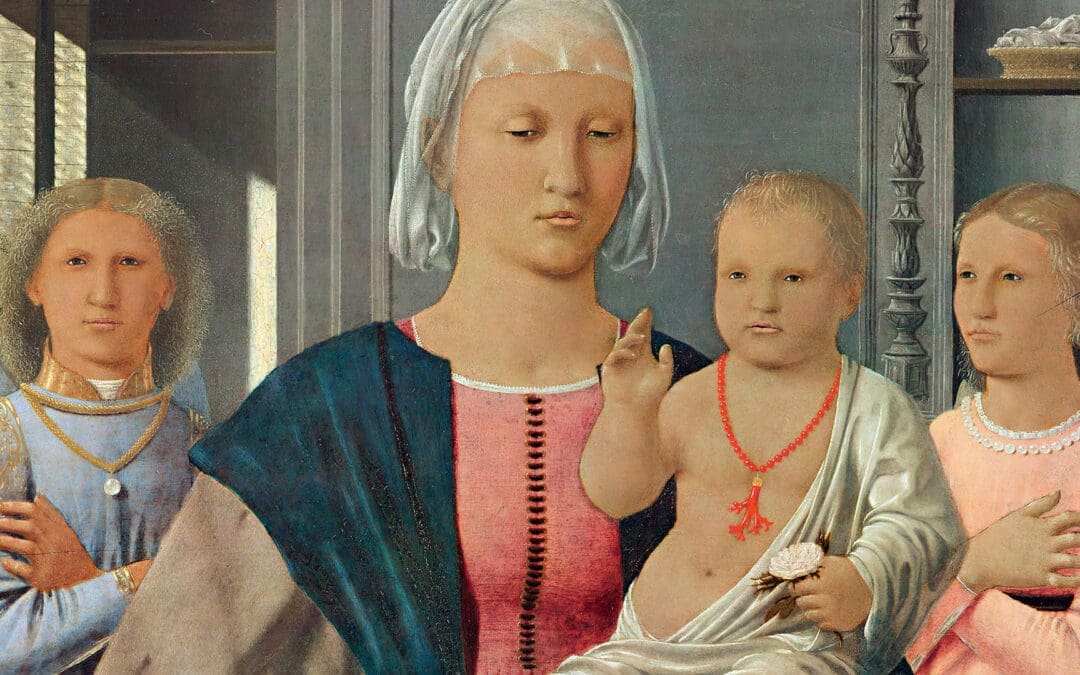

This is the question of the spiritual life. For me, the balance of these questions has become framed in a most inconspicuous source: Andrej Rublëv’s Icon of the Holy Trinity. This fifteenth-century Russian icon is at once an image of the Lord’s visit to Abraham under the Oak of Mamre, and an image of the Triune God: Father, Son and Holy Spirit. As I have prayed with this icon, I have found it encompasses the range of disciplines that fund sustainable spirituality for the Christian activist in North America.

Living in the House of Love

The first thing I notice when I look at this icon is the angelic visitors in the foreground. In their faces I see an intimate communion with an ancient history. It is timeless. Their love for each other is evident, as is their invitation to join in that communion. Thus, the first thought which comes to my mind is relationship—the gift of our relationships to one another.

For the Christian activist, this first gift can be the hardest to accept. Making a serious, sustained effort to be in God’s given communion—to be in the Church—is no picnic. Paul Tillich, in The Protestant Era, writes particularly of Protestantism as a “highly intellectualized religion” making “the minister’s gown of today. . . the professor’s gown of the Middle Ages.” Services and theologies can seem intellectual.

But look further into the background behind the visitors; see a hill, a tree and a house. The icon is drawing us into the Gospel story and its final consummation in the communion of the foreground. The authority of this communion, or of the Church and its pastors and priests, is not rooted in intellectual or rhetorical skill—it is relational. Truth is not a matter of logic, but of relationship. And so it is never something we possess, but something—or rather someone—we encounter, to whom we bear witness. This is what the Proverbs mean when they talk of the “fear of the Lord” as the beginning of wisdom—not merely as a good epistemological anchor, but a person who gives truth meaning, apart from which there is only meaninglessness.

I think of the role of pastor as more of an elder or priest in a tribal village: he or she is the keeper of the sacred stories, responsible for telling them over and over to provide unity, purpose and identity in the community. The authority of that elder is not intellect, but calling—an answer in relationship. They have been deeply formed in the story of the community and it is their task, in turn, to form us in that deep mystery. In her reflections on the Old Testament trinity, Frederica Matthewes-Green writes, “There is no such thing as theology that is purely intellectual. If it does not change you, if it does not flood you with light, it is not worth your time.”

As long as we think of the authority of the Church as an intellectual authority, public life Christians won’t take it seriously. After all, we know there are brighter people out there. It seems to me that this is often why activist Christians have a marginal enthusiasm for church or—and this is becoming more common—abandon popular evangelicalism altogether and embrace a high Anglo-Catholicism, which often takes more seriously the rooted traditions and story of God and his people. By rethinking church as primarily story-formation rather than intellectual edification, we begin to unpack why we are called and required to be in such a communion. Being part of the community of the people of God, where people might behave and look different but share the same hope, is not so much dressing on the work of public life. Stories must be told in community to be lived in authenticity, and the Church is God’s gift to that end.

Silence, Prayer and Sabbath

Second—notice that none of the figures are speaking. The icon draws us to silence.

Silence and solitude is not just “alone time” apart from our usual frenetic pace. It is more than a time-out from people. Henri Nouwen writes in Clowning in Rome that “solitude is the very ground from which community grows.” It is untrue that the only times we grow closer together are when we are with each other. If life is based on our proximity to each other, to our time speaking and practicing together, we quickly become drowned in a drone of activity and our lives fluctuate according to moods, personal attractiveness, mutual compatibility and utility. Solitude, by contrast, puts us in touch with a unity that precedes these things. Nouwen writes that when we enter into solitude, “we witness to a love that transcends interpersonal communications and proclaims that we love each other because we have been loved first.” Contemplative prayer reinforces this space for God, drawing us to an openness to taste and see God in the disparate spaces of our lives. It is directed silence, not merely imposed silence. The life of the Christian activist is filled with words and activity; silence and contemplative prayer are rituals that anchor us, again, in the drama of Scripture and story of Christ’s Church.

In silence we rediscover that we are utterly dependent on God. In conventional paintings, things grow smaller as they go into the distance, until a “vanishing point” is reached. But icons often play with perception, reversing or distorting perspectives to increase our awareness of being off-balance in an unfamiliar, powerful world where a scene rushes out at us. In Rublëv’s icon, the chalice in the centre presses itself our way, an urgent invitation to sacramental communion. The vanishing point becomes right about where the viewer is standing. And so the viewers are the vanishing point. The message is clear: but for God sustaining us, we would vanish.

Third—these figures are at rest. Sabbath is the work of silence. When our words stop, so also do our activities: for six days we labour and create in the world, but on the seventh we remember that we are creatures and so we cease—for a time—and are directed toward God. This icon tells us to stop, to be silent. But Sabbath, like silence and contemplative prayer, isn’t about a frustrated pause or like a trip to the spa to relax: it is a ritual that reorients us, especially activist Christians, away from our own skill, acumen and capability and calls us—in community—to know we are limited. A ritual Sabbath ensures that the bricks of culture that we lay are for Cathedrals, not Babels— oriented, even if in broken and partial ways, toward the true worship of God.

Space for God

Fourth—we see the open space of our own invitation. This sacred space is prepared for us, and yet is a space that also exists within us. The icon is made in the form of an invitation. Everything about it draws the viewer into the empty space to sit and join in the picture.

“Space for God,” curiously, is Thomas Aquinas’s definition for celibacy. Celibacy in contemporary usage seems more concerned with the act of sex than the space which its absence is intended to cultivate— more a commentary on our relationally degraded culture than the monastic practice itself. If work and words can overwhelm the activist, so too can human relationships. Certainly in the last few decades, the values of coming together, being together and living together have been widely recognized. What could be more important in a fragmented and isolated society, where people suffer deeply the brokenness of individualism run amuck?

Yet if the monastic literature on celibacy is any guide, we know that human intimacy—even that in the vocation of marriage—really can’t go about filling every space within and between us. We know this in our heads, but the loneliness of North American culture—mirrored in so much of contemporary evangelicalism—leads us to expect it anyway. Deep within the human heart exists sacred space in which God alone dwells. When we forget this truth we become disillusioned and easily become resentful, bitter, vengeful and even violent.

Sadly, I believe that when we “focus on the family,” our defeat is already realized. No loss in North American Protestantism so disillusions me as that loss of monasticism and celibacy. For in our rush to fill the voids, the emptiness and the meaninglessness of our materialist lives, we have retreated to the vocation of marriage and family as a final stronghold in which to find intimacy and communion. Ironically—and it is an unhappy irony—when we make the family our focus, our families are in more danger, collapsing under the weight of impossibly unmet emotional expectations.

The folly of celibacy, as Nouwen writes of the “clowns of Rome,” is the witness to the solution for those problems that vex us, and here we see it plainly in Rublëv’s icon: God. We have disordered loves—as David Naugle or Alasdair MacIntyre might argue—forgetting the source of our true good, by whose attainment all of our institutions and vocations (marriage among them) are daily renewed and restored.

And so interior celibacy is something that I am convinced even the vocation of marriage can practice. Marriage, after all, is not the lifelong attraction of two people, but a call of two people to witness to God’s love. The real mystery is not how their love helps them discover God, but how God’s love for them helps them discover each other. This picture of celibacy is akin to the holy invitation we see in the icon to take our place at the open side of the table preserved for us. And so we also preserve space within ourselves for God, and by so doing, learn to love more intimately and inclusively while weathering the storms of relationalities that come and go in the activist’s life.

The Narrow Road

How do we answer this invitation and take our place in the empty space? The Spirit—the third visitor—points to the answer, toward the tomb in the centre of the altar. Here in this rectangular space, we see the narrow road leading to the house of God. It is a road of suffering. While the four corners remind us of the created order, its position in the altar signifies that there is room at the divine table only for those who willingly participate in the divine sacrifice by offering their lives.

This narrow road ensures that we (in North America, particularly) take seriously Jesus’ warning that few things are harder than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven. We are awash in material wealth, but even more, we are deeply enmeshed in the story of global capitalism. Our calling is to live a very thin line between affirming the good potentials of business and markets and speaking prophetically against the abuses and extremes of an unrepentant consumerism. My hope is in what Jesus said: with man such things are impossible, but with God all things are possible. And this icon does give us a few clues about what sort of disciplines sustain prophetic witness in the midst of wealth, which so easily freezes the heart and mind.

First, we must give. Radical giving is an enactment of the story of the Gospel. It is gratuitous and outrageous to offer our first fruits—that which could be used for constructive (even Kingdom!) purposes. Yet, there is the Lamb of God at the altar across the table from us. What radical giving we have been called to imitate, that our love should mark us as God’s own! This kind of giving invites us to remember that God is, and we are not, the beginning and the end of cultural transformation, of capital market reformation and political emancipation.

Second, this kind of sacrifice invites us to live more simply. The monastic witness is voluntary poverty. But even outside the cloister, Christian simplicity can be an important discipline which preserves our life against the pernicious and subtle idols of unlimited growth. Wealth and luxury are no sin, but the temptation is real and the idols are subtle. It is wisdom in such a context, in the times in which we live, to stay alert to Jesus’ warning by ritualistically re-enacting the gratuitousness of the Gospel in radical giving and simple living.

God with Us

A final part of the icon I want to focus on is the paradox of the staffs that each of the figures have in their hands. Why a paradox? Look at the three angelic visitors. Each has a pair of majestic golden wings which—we are led to understand—are more than merely ornamental. Surely walking staffs are something far beneath such glorious creatures. Here we see that God is truly with us. Just as in God’s sacred visitation to Abraham under the oak of Mamre, we learn that, mercifully, our journey into the heart of God and into the hope of the world is not from merely within ourselves. We see in this icon that even the simple task of preparing that sacred space, that faith within our hearts, is an act first and foremost of God. Before we reached out to God, he reached out to us, became human and made his dwelling among us.

When I see these three angelic visitors bearing staffs, I am drawn to confess that no activity or talent of mine is sufficient for even my own salvation—to say nothing of the world. Ultimately, no combination of rituals or disciplines makes God present to us. It is he who chooses to join us, to enter into our journey, our slow movement across the face of the earth. We see here feet that are tired from dusty travelling. God is with us in the weariness of the human road, not floating majestically overhead. The message of this icon to the task of Christian activism is that while God is joined with us, we do well to remember that he was before we were and made himself known to us for the salvation of the world. Not even our simplest prayers take flight apart from the active sustenance of God. We are totally and utterly dependent on his continuing revelation.

Conclusion: Story-Telling

The question of doing public life and still believing “stuff” is ultimately one of narrative living—a storied enactment which provides us, again and again, with a rooted cosmopolitanism by which to live and work in the world of public life. Our traditions and our rituals are the sacred grist for the mill of public life; without a robust rediscovery of tradition and ritual—of daily practice—our journey collapses under the weight of unmet spiritualistic expectations. We continue to perform the actions, for a time, on autopilot. But these soon cease, striking us as empty and hypocritical. In some cases we break down. Other times we simply wither away and move off.

In After Virtue, Alasdair MacIntyre writes that we are storytelling animals. He argues we can only answer the question “What am I to do?” if we can answer the prior question: “Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?” The question of sustainable spirituality for activist Christians is essentially one of storytelling and formation. Public life believers have a barrage of contradictory narratives storming about them daily: stories about wealth, power, beauty, intellect, social status, accomplishment and intimacy. And this barrage is as it should be if we’re practising public life rightly. We should feel the tensions of our times and not close ourselves off to the passions and hurts of the people around us. But to be rooted in the Gospel in that context means we need to be up to more than the bare minimum: we need the resources and rituals of the Church’s history and hard fought disciplines that can sustain hope in troubled times. Then, as Jamie Smith writes in Who’s Afraid of Postmodernism?, our storytelling will be supported by our story living. And then—maybe—we can do public life and still believe stuff.