The story of Christian philosophers in the North American academy over the past thirty years provides something of a case study in persuasion. Fifty years ago, the discipline was staunchly secular and dismissive of religious perspectives. Today, Alvin Plantinga’s book on science and religion, Where the Conflict Really Lies, received an appreciative review from Thomas Nagel in the New York Review of Books, and Plantinga was invited to review Nagel’s latest book in the pages of The New Republic. In the meantime, Christian philosophers such as Eleonore Stump, Peter Van Inwagen, and Nicholas Wolterstorff, along with Plantinga, have served as presidents of the American Philosophical Association. Something changed. But how did that happen?

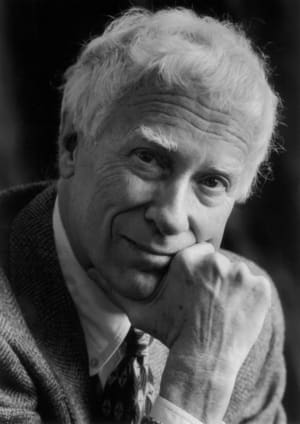

I sat down with Nicholas Wolterstorff for a conversation about how that change happened—and how it might be instructive for people in a wide array of fields. As part of the generation that challenged the assumptions of the discipline, Wolterstorff is both a respected scholar and a public intellectual—as interested in the shape of the academy as in the life of the church. After teaching for thirty years at his alma mater, Calvin College, Wolterstorff became Noah Porter Professor of Philosophical Theology at Yale University, a position he held until his retirement in 2001. He is now a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia. (His latest book, Justice in Love, is reviewed elsewhere in this issue by Cardus Senior Fellow Jonathan Chaplin.)

JS: Over the past thirty years or more, there’s been a renaissance of Christian philosophy. I wonder: when you were entering the field as a young scholar, would you ever have envisioned that as possible?

NW: No. When I entered the field as a grad student in 1953 at Harvard there was no course in philosophy of religion. Or if there was, it was so inconspicuous that I took no note of it. I did not find my professors hostile. They knew who I was. I think their attitude was maybe the typical Weberian attitude, that religion is a relic. “He seems like a bright young fellow. A bit idiosyncratic in being religious, but so be it.”

Logical positivism was in its heyday. When I was a grad student, probably in my third year, an anthology came out edited by Antony Flew and Alasdair MacIntyre, New Essays in Philosophical Theology. I was eager to read it; I bought a copy almost as soon as it became available. I was extremely disappointed. It would be interesting for me now to reread it sometime.

The tone that came through was a very worried tone. It was a positivist worry: can we even talk about God? It was not really philosophical theology; it was instead reflections on the question, “Can there be such a thing as philosophical theology?” written by people who quite clearly wished there could be such a thing. But it was not philosophical theology.

Then what happened? What happened in my field of philosophy was that positivism collapsed. Oxford ordinary language philosophy, which had been competing with positivism for a decade or so, collapsed at about the same time. Consequently, by the early ’60s to mid-’60s there was no longer any big program in philosophy; none; and there still isn’t. The big programs in contemporary philosophy had all been gatekeepers: the positivists were saying that one can’t even talk about God, the ordinary language people were worrying whether language is being used improperly when we talk about God, and so forth. The collapse of the big gatekeeper programs meant that there was nobody around anymore who was saying, not with any plausibility, anyway, that it’s impossible to make judgments about God, impossible to talk about God, etc. All of those programs collapsed. They did not collapse because of what they said about the impossibility of religious/theological language; they collapsed for other reasons.

What this collapse meant was that religious/theological discourse was now open. People would disagree with it; but they could no longer say, “You’re talking nonsense,” or “That’s not what one would say if one were speaking proper English,” or “What you are trying to say is beyond the bounds of the sayable,” or anything else of that sort.

JS: The implosion of the discipline’s gatekeepers opened the space for Christian philosophers to be able to speak.

NW: Of course there had to be some people who would walk into that space; if the door had been opened, but nobody had walked through it, nothing would have changed.

JS: Would you have guessed, when you decided on philosophy as a vocation, that these changes suggested an agenda for you?

NW: No.

JS: So it was not like there was this group of Christian philosophers in some smoky backroom who were sitting around hatching a plot to change the field?

NW: No. We began with much more modest ideas than that. I was a graduate of Calvin College, a convicted Kuyperian. So I did not think that philosophy was some sort of “neutral” enterprise. I thought one engaged in philosophy qua Christian, or qua materialist, or whatever. My hope was that there would be space for me, and friends of mine, to engage in philosophy qua Christians. I don’t think we visualized much more than just having space to do that.

JS: Did you have a sense that there were others of your generation who had come to a similar place? Or is it only looking back now that we in following generations see, well, a kind of “crew?”

NW: A phalanx of a sort.

JS: And a vanguard in many ways.

NW: My sense at the time, as I recall, was that initially it was Al Plantinga and myself. We talked to other people. George Mavrodes from the University of Michigan soon came on board. Al had gone first to the University of Michigan as a grad student and then to Yale. He had Bill Alston as a teacher at the University of Michigan, so he knew Alston. And Alston became sympathetic. But we did not think of there being a big phalanx.

The next thing that happened, as I recall, was this: after a short time, Al and I were both back together as young professors at Calvin College. We said to ourselves, “We should really talk to the philosophers at Notre Dame; we should get together on a regular basis.” So we did that. Twice a year we got together with the Notre Dame philosophers, once at Calvin, once at Notre Dame. We must have done that four or five years running. As I recall, it was really out of that back and forth between the Calvin philosophers and the Notre Dame philosophers—of which there had been nothing of the sort before—that the Society of Christian Philosophers was formed. Contacts among Calvinist and Catholic philosophers who were all trained in American universities within the analytic tradition.

JS: You went on to become president of the American Philosophical Association. For my generation, that’s still a remarkable achievement. Obviously that meant you were getting a hearing and were respected well beyond the confines of Christians. I don’t think anybody would ever confuse your strategy with some kind of strident apologetics or something like that.

NW: (Laughs) No.

JS: Yet you are unapologetic, right?

NW: That’s a good way to put it, yes.

JS: You are unapologetic; but your mode of operation has clearly not been to trump. You’re not any sort of academic bully. Have you thought much about what your methodology was? How did you position yourself in the field to get that kind of hearing and respect?

NW: I suppose a good deal of it was this: I was not trained to think of my role, as a Christian philosopher, as mainly that of combatant. I don’t know that any of my teachers at Calvin ever sat me down to say the following, but nonetheless what came through was this: philosophy is a human enterprise. It’s not a Christian enterprise. It’s not a humanist enterprise. It’s not a naturalist enterprise. It’s a human enterprise.

And we participate together in this enterprise, in so far as that is possible, talking with each other, discussing issues together, sometimes agreeing, sometimes disagreeing, and taking it from there. That’s the picture I received: being a participant in the shared enterprise of philosophy—from my own worldview, however, participating with others who engage in the enterprise from their worldview. I think it was this sense of being a participant in this shared enterprise, rather than a combatant against the enterprise, that was crucial.

JS: In a way there was a levelling of the playing field because of the earlier implosion [in the discipline]. You felt that we did not have to apologize for sharing in the enterprise but doing so from your own Christian worldview.

NW: Right.

JS: But then you also didn’t think that you had to run the show.

NW: Right, both of those. Nobody was saying, “Your perspective is illegitimate” or anything like that. But we also weren’t trying to run the show. Another important point is something that I repeatedly point out to young people: you have to be good at it. You have to work hard, and be well-trained. People who think they can just lob grenades and gain a hearing, they’re just wrong about that.

JS: You have to earn your stripes. Do your homework. Be a full-fledged participant, just as you said, because it’s a human, shared project; don’t instrumentalize your participation with the aim of taking over.

NW: Exactly. I participate in this shared human project of philosophy. I speak with a Christian voice and think with a Christian mind; but I do so as a participant in this common project. My first book was in fact not about religion but about universals; it was a book in metaphysics.

JS: Yes. Your earliest work, when you start making this dent, was not about religion.

NW: Al’s work from the very beginning was about religion; but I had become intrigued with metaphysical questions.

JS: And then later aesthetics.

NW: Then later, aesthetics.

JS: Then your work on Locke, and then, obviously, justice. All of these are themes that have purchase beyond the Christian community.

In the introduction to your big book on Justice, you describe your approach as “Anselmian.” What did you mean by that?

NW: “Faith seeking understanding,” basically: thinking about the issues of justice from the Christian perspective or worldview. (I don’t much like the term “worldview,” but I’ll go with it here.) Not trying to give an apology for my worldview, not trying to defend it, also not setting it off to the side. None of those; but thinking about matters of justice from within my Christian worldview.

It appears to me that almost all analytic philosophers have tacitly settled into an Anselmian understanding of what they’re doing—though most of them would not call it that.

JS: Yes. You say something similar in that same introduction, and I remember being struck by it: the Christian philosopher is in the same situation in this respect as most philosophers. We all begin from some sort of set of fundamental commitments. We are not trying to demonstrate those or prove those, but trying to answer the question, “What does justice look like, if that’s my starting point?”

NW: “How do philosophical issues look from a naturalist perspective, for example.”

JS: But clearly your audience isn’t people who only share your worldview or your commitments.

NW: Right.

JS: So how does that work? How do you say, “I’m going to think through, say, these matters of justice, and here’s my starting point. But I don’t just want to write for an enclave. I want people to hear this as a viable argument in the public sphere of ideas.” How do you do that without losing people who don’t share your starting point?

NW: Roger Lundin, from Wheaton, once suggested to me a good metaphor for this. He said to me, twenty years ago, I suppose, “You philosophers found a voice long before the rest of us did.” That’s a very good metaphor. You have to find a voice whereby what you say can be heard. When I try to explain that idea to fledgling students, I give them an actual example from my Yale classroom. Every fall I would teach a sizable lecture course on the philosophy of religion, around a hundred students. They would be from all over the university: undergraduates of all stripes, people from the divinity school, sometimes some from the med school, from the law school, or wherever.

There would always be students in the class who had graduated from some evangelical college. And invariably it would happen, about five weeks into the course, that a male from an evangelical college, never a woman, would raise his hand and say something to this effect: “Well, as Jesus says in John 5 verse 37 . . .”

JS: End of conversation.

NW: End of conversation. By then I more or less knew which of the students were Jewish, which of them professed to be atheists, and so forth. I would look out at them, and their eyes would be getting round. They would be squirming, whispering to each other, and so forth. So always after class I would take this student aside. I remember one of them, David, very vividly. I took David aside afterwards and said, “Look, David: you can ask approximately that same question, but you have to remember that this is not a Wheaton campfire Bible study. This is a Yale philosophy classroom. You have to ask your question in the right voice.”

Then David says, “What’s the right voice?” I said, “I don’t know how to explain it.” (Laughter) “You seem bright. Why don’t you just hang in there for a while and listen. I bet you’ll catch on.” David caught on very well.

JS: Interesting. Part of finding the right voice is knowing how to translate yourself for wider audiences and, I guess, expecting a certain sympathy—or hoping to earn a certain hearing for your voice, because you’re being hospitable by meeting people where they are.

NW: Exactly. How can I tap into their mode of speech, their concerns, their wishes and questions? In my experience, what often happens is that evangelicals speak in a thoroughly non-accommodating evangelical voice, to which they get a perplexed if not hostile reaction, and then they say, “See? There you have it once again. The university is hostile to evangelicals.” My reply is, when you talk like that, what are the other people supposed to do with what you say?

JS: Right. They can’t even receive it, in a way.

NW: They can’t even receive it.

JS: And to those who would worry that what you’re describing sounds like concession. . . . In fact it’s not because, again, I’m thinking now of the end of the Justice book where you make this really remarkable and quite bold argument that the secularist doesn’t have the resources to ground human rights. You suggest that it seems that the only way to truly ground human rights is to ground them in the fact of every individual’s being loved by God.

NW: Right.

JS: But you present your argument in a way that, while unapologetically Christian, can at the same time be genuinely heard by others.

NW: I trust that it does not come across as “in your face.”

JS: No, not at all.

NW: It’s preceded by lots of pages in which I say, “Let me hear what arguments you have.”

JS: At points you are almost sympathizing with the plight of the secularist, like, “I wish we could ground human rights more broadly.” So I think your strategy there is really instructive for folks who are trying to do work in public spaces where they actually want to move the conversation. How was that last part of your argument in Justice received?

NW: With annoyance by some people.

JS: Is that right?

NW: Yes.

Jeff Stout, for example. You know Jeff?

JS: Yes.

NW: Jeff was annoyed with it.

JS: In some ways I thought Jeff was the consummate audience for that point.

NW: Yes, in some ways he was.

JS: He would be so sympathetic with everything else that you were saying.

NW: Right. So I told Jeff, and others who wrote me about my argument, “Look, I’m open to your giving me a successful secularist argument.” He offered me one that was, in my judgment, very weak.

JS: So this is still happening on the terrain of arguments. But somehow it seems to me the strategy here is a mode of persuasion that is different from a knockdown, dragout proof. Do you know what I mean? Is that the “Anselmian” part of it?

NW: It’s an aspect of the “Anselmian” approach, yes. It’s not an argument that says it’s inherently impossible for a secularist to find a good defense or grounding of truly human rights. It’s rather, “I looked at your arguments; none of them seemed to me to work, and I can’t think any of any arguments along the lines that you propose that will work. I’m open to suggestions. But as things now stand . . .”

JS: I’m wondering whether your epistemology primed you to see why not all of your arguments would be successful in persuading those who don’t share your starting point?

NW: Yes, you’re right about that.

JS: So in a way what counts as success for you is going to be different because of that epistemological framework. Is that right?

NW: Yes.

JS: Do you judge the success of that last section of Justice on its ability to change people’s minds, or on something else? Would you have said, “That argument really worked because now Jeff Stout thinks differently,” or is it something else? Have you at least moved the conversation in a way, and does that count as a success?

NW : Yes, I certainly think I moved the conversation. Some people thought that I was arguing that it’s irrational for a secularist to believe in human rights. That’s not my view. It’s the philosopher’s standard predicament to be thinking about some phenomenon that he or she thinks exists, and to be unable to account for it. You believe, for example, there are obligations, so you think hard about trying to explain what grounds obligations. But you find yourself unsuccessful. But you don’t then say, right away, “There must be no obligations.”

So from the fact that secularists have not found a successful grounding for human rights, it does not follow that they should give up on human rights.

JS: Which would be the last thing you would want.

NW: It would be the last thing I would want. Part of what was going on in my line of thought was this: as you know, a standard story about human rights is that they are the invention of the secular, anti-Christian eighteenth century Enlightenment. Some people think, “Hey, bravo. Really, really good.” Other people (Hauerwas and others) think it’s horrible. But they all accept the story.

A big part of my argument in the book is that the story is mistaken. I would not have known that it was mistaken if I had written the book twenty years earlier, before research appeared on what the canon lawyers of the 1100s were saying. What that research shows is that the twelfth century canon lawyers were systematically employing the idea of human rights. I did not myself do that research. It just appeared at the right time for my work.

Part of what was going on in my book, then, was the systematic pursuit of the implications of that new story. Not only is it not the case that human rights were the invention of anti-Christian eighteenth century secularists. It’s the other way around: Christianity is the source of the idea of human rights. Further, it can provide a grounding of those rights whereas the secularist cannot—or has not.

JS: There are two flanks that you’re countering. On the one hand you are countering those Christians who demonize the rights tradition as if it were only a secular project, while at the same time you are pressing the secularists to realize that they don’t have the ontological resources to ground rights. They don’t have an account.

NW: As it turns out they also do not have the historical story correct.

JS: I find that interesting. A big part of it, then, is retelling a story.

NW: Yes. I think of the book in good measure as retelling the story.

JS: It strikes me that there is a mode of persuasion that is uniquely narratival. In that sense, even though you are writing different books, this is very similar to what Charles Taylor is doing in A Secular Age where he counters just-so stories about the emergence of the secular. He says, “No, actually there’s a different story to be told here.” It strikes me that there’s something unique about narrative, stories, and alternative stories as modes of persuasion, that’s worth thinking about.

NW: You’re right. Of course one has to have the evidence for one’s re-telling.

JS: Of course.

Let me circle back at the end here to one thing that you said before. Roger Lundin said to you, “You philosophers found a voice early on so that you could be heard by your fellow philosophers.”

NW: And he was comparing philosophy to other fields.

JS: I know that when I talk to people in other disciplines they are often sometimes a bit envious of the legacy that people of my generation have because of the vanguard work that you folks did. Now one can see this starting to happen in other disciplines. I am thinking, for example, that a lot of Christian Smith’s methodological work in sociology today is, in a way, trying to push back on the standard sociological story and its big account of what human beings are.

NW: Yes, he and James [Davison Hunter] push back on the reductionist metaphors that have haunted contemporary sociology.

JS: Exactly. In turn, they get incredible pushback. In some ways it would be interesting to compare whether you guys [in philosophy] felt the same amount of resistance that these sociologists are feeling today. I don’t know. Maybe the discipline of philosophy was in a different state.

NW: Hunter and Smith do get a lot of push back. I looked up, for example, whether Hunter was in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He’s not. [Robert] Wuthnow is; but James is not. But James is as distinguished in the field of sociology as pretty much anybody.

JS: This probably says something about the regnant orthodoxies within the field.

NW: Right.

JS: So I wonder: if someone was looking at philosophy as a case study of how Christians can have a persuasive influence in the field, do you see anything that’s transferrable for scholars in other fields—in terms of mode of persuasion, the way one works to change minds in one’s field, and so forth?

NW: Part of why Chris and James get the push back, more so than, say, Allan Wolfe and Bob Wuthnow, both of whom do many of the same things, is that they challenge the methodological assumptions more directly. That’s true. Wolfe and Wuthnow just proceed.

JS: Yes. They do very, very good and careful work in their field; so they’ve earned respect because of that.

NW: Right. Hunter keeps telling me that most sociologists have hired themselves out to the government as statisticians. I imagine that’s a bit hyperbolic. (Laughs) But a lot of sociological work does indeed consist of gathering statistics for governmental agencies. If a fellow sociologist then comes along and says, “Look, the methodological foundations of what you are doing are just rotten,” he will be seen as imperiling the livelihood of half of the profession. He can be assured of getting pushback. You and I don’t imperil the livelihood of any of our fellow philosophers. (Laughs)

JS: It maybe speaks to the fact that disciplines have histories, which means that one is always at a particular time at a particular place in one’s discipline. So any mode of persuasion is always going to have to be contextual. What you’ve been saying is there was this right season of opportunity in philosophy that is probably not replicated, or even replicable, in other fields, at least not yet.

NW: Exactly so. In the field of literature there was nothing like these big-brand gatekeepers who then suddenly died off.

JS: It’s probably helpful to know that what happened in philosophy cannot be reduced to some formula that can just be applied in other fields.

NW : What happened was indeed highly contextual.

Not entirely contextual, however. There are some transferable lessons: the matter of finding a voice, for example, of being well-trained, of working hard, and so forth. But the situation in philosophy had its distinct contours; and those made possible what happened.

JS: And if people want to make an impact on their own fields, it’s really crucial that they be attuned to the particularities of their context, time, and so forth.

NW: Right. I sometimes use the following metaphor when I speak to upcoming scholars: You have to find the points where you can rest your pry bar.

JS: That’s great.

NW: The point where you can start prying, so that the other person says, “I hadn’t thought about that. I’ll have to go home and think about that for a while.”

JS: And the place where you can rest your pry bar will be different in each field.

NW: I as a philosopher cannot tell the person in English where to rest his or her pry bar.

JS: I think that’s a really good lesson. Otherwise we fall into the same trap that churches fall into: “This church was really successful. Ergo, let’s go replicate that church in this other context.”

NW: Yes; seven steps to success, and so-forth.

JS: Exactly. I think it would be really helpful if folks would come away from your reflections on these matters and say, “Okay, there’s no formula here. But there are goals and intentions that can be pursued.”

NW: A person in literary studies, for example, has to ask, “What is the state of literary studies now? Where are the weaknesses that I can probe in such a way that my colleagues will say, ‘Hmmm . . . you’ve got a point. I’ve got to think about that.'”

JS: It would be great if we could count it a success to get our peers to say, “Hm.” It’s not a culture wars agenda. It’s much more modest than that.

NW: One would like to persuade. But before the persuasion, the goal is to get the person to say, “Hm. You’ve got a point. I’m going to have to think about that.”