So you say you want a revolution? There are plenty on offer. Indeed, who’s not staging a revolution? The billboards on both the left and right shoulders of the campaign trail offer a revolution to suit your fancy—whether it’s the demolition of government as we know it or the demolition of capitalism. Bernie Sanders’s campaign embraced this revolutionary branding, and even when he finally endorsed Hillary Clinton he promised that “the revolution continues.” His forthcoming book leaves little doubt: it’s titled Our Revolution.

But so-called conservatives are no less prone to revolutionary intentions. The anti-government senator Ted Cruz regularly promises a “new revolution” that starts by razing half of Washington, DC. And the Republican nominee Donald Trump, who has torn up every page of every prior playbook, launched his unlikely campaign by hoping for “a positive revolution.” (Not to be left out, we might note here in Canada that the video game Deus Ex: Human Revolution drafted Justin Trudeau as prime minister four years before it happened.)

You half expect a leftist senator who honeymooned in the USSR to promise a revolution. And you pretty much expect a disappointed and deflated younger generation to join the cause. But when even conservatives—people who are supposed to value conservation—march under revolutionary banners, it signals a paradigm shift: revolutionism is now the ethos of our society.

Revolutionary fervour is the new status quo. In a sense, our politics has really just caught up to the culture of the 1960s, a decade that launched revolutions of expressive individualism that snowballed into the sexual revolution, the upending of higher education, the dissolution of industries, and more.

You can barely get a hearing anymore unless you plan to burn everything to the ground (as long as Twitter and Snapchat are left unscathed so the revolution can be broadcast). From presidential campaigns to campus politics to the entrepreneurial penchant for “creative destruction,” an almost flippant craving for revolution mobilizes voters, consumers, and even slacktivists who rarely consider just who pays the price for their revolution or that their revolutionary energy feeds on stability.

Now, there is something understandable about this. If the only options are the status quo or revolution, who wouldn’t man the barricades? We are all too familiar with the failings of the status quo and the injustice of the regimes we inhabit. We live with a constant awareness of having been dismissed and barred from Paradise, still a million miles away from kingdom come. No one needs to convince us there’s something wrong. Isn’t it up to us to put the world to rights?

In this respect, our public imagination has been hoodwinked by a false dichotomy: either the status quo of injustice or the justice of revolution. But whenever someone offers you two options you should immediately ask: Isn’t there a Plan C? And more poignantly: whenever someone promises the Revolution will solve our problems, you should always wonder: Who’s “us”? And who are we entrusting ourselves to? What fallible human beings have the wisdom to start over from scratch? What sort of hubris does it take to assume that everyone before us had it wrong? Why should we think we’re any different?

Every revolution is rooted in confidence in some new Enlightenment. As Françoic Furet comments in his classic study, Interpreting the French Revolution: “Every revolution, and above all the French Revolution itself, has tended to perceive itself as an absolute beginning, as ground zero of history, pregnant with all the future accomplishments contained in the universality of its principles.” The revolutionary, we might say, elides the Creator/creature distinction and assumes the role of ex nihilo creator. Revolutionaries refuse any inheritance, deny any debts, confident that their technocratic enlightenment is just what the world has been waiting for. Behold, we make all things new. In this issue of Comment, we critically consider the way this revolutionary zeitgeist has affected the family, business, art, politics, and more—and suggest a different way forward.

What has been eclipsed in our revolutionary age is precisely a robust vision for reform as a wise, strategic, faithful pursuit of justice and the common good. There might be ways to effect change that don’t require scorched earth, all-or-nothing reengineering of everything that’s preceded us.

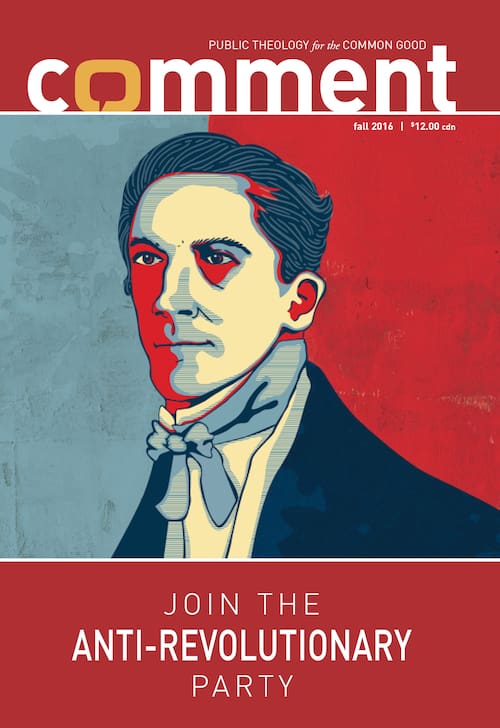

We’ve been here before. In fact, some of the intellectual lights of the Reformed tradition—ones that illuminate our work here at Comment—shone brightest in the shadow of the French Revolution. In 1845–1846, the Dutch statesman and historian Guillaume Groen van Prinsterer delivered a series of lectures that would later be published as Unbelief and Revolution. Akin to Edmund Burke and anticipating Tocqueville, Groen was interested not only in the revolutions of the past but also in a new revolutionary ideology that had taken hold of Europe (1848 was just around the corner). Based on the abstractions of Reason and a supposedly timeless ideal, this revolutionary zeitgeist treated all of society as a blank slate for rationalist social engineering, unhindered by tradition or tribe. The result was a “nation-building” project as if the nation was born yesterday.

Very much related to this, on Groen’s account, was the link between revolution and unbelief: encasing the political within immanence, the revolution would divinize the state, deify the Volk, and realize a rationalist heaven on earth. Heaven help the people who stand in the way of revolutionaries who know what’s good for “the people.” Indeed, it’s unsettling how much Groen saw the future that is our present. In a dire but prescient footnote he observes:

The most remarkable, indeed the most awesome thing about these [revolutionary] doctrines, once you are pleased to notice the source of the universally accepted Revolution principle, is not their fallacy but their irrefutable correctness: where there is no belief in the living God, socialists, communists, atheists, the champions of the Republic of the colour of blood, are in the right. Only when he keeps this revolutionary consistency in mind can one account for the fanaticism which regards realization of the doctrine as the most noble mission, resisting it as the most culpable crime.

This critique of revolution would be woven into the DNA of Abraham Kuyper’s political and social vision. In fact, the political party he founded took on the moniker the Anti-Revolutionary Party. It’s a party we invite you to consider joining. But this isn’t just an invitation to a political endeavour. It’s an invitation to a different posture, one that resists the revolutionism of our contemporary zeitgeist precisely because we, as an eschatological people, inhabit time and history differently. That’s why we think we have something to learn from those who have preceded us, who can teach us why reform is a more faithful, more just endeavour.

At the time that Groen delivered his lectures, the French Revolution was only fifty-six years in the past—exactly our distance from 1960, the beginning of the revolutionary era we still inhabit. So perhaps it is an apposite moment to revisit his seminal critique of the revolutionary ideology—especially since it now seems to be the default of late modern liberal societies, the water we swim in without noticing.

So this issue of Comment is unapologetically “educational.” We want to introduce contemporary readers to the anti-revolutionary posture of the Reformed tradition, and the Christian tradition more broadly. (One could easily imagine G.K. Chesterton or Christopher Dawson nodding in agreement with much of Groen’s concern.) But we are not interested in this merely as a historical episode. Rather, we see this Reformed critique of the revolutionary zeitgeist as an instructive model for today. The cautionary posture, the incisive critique of idealism, forthrightly pointing out the implications of unbelief—these are lessons that are as timely as ever in our current milieu, where a revolutionary zeitgeist captures both left and right. Ultimately, refusing revolutionary hubris is a way to relearn how to be creatures, but now in a way that is tied to eschatological hope. Because we await the parousia, we are liberated from revolutionary hubris, even while we are called to—and caught up in—Christ’s renewal of all things.