One of the saddest books of the modern world is Mark Bittman’s How to Cook Everything—not because the plot is heartbreaking (it’s a cookbook) or because it documents the ravages of hunger. What’s sad is that we need it: it’s a cookbook for a society that forgot how to cook.

In The Table Comes First, Adam Gopnik sketches the evolution (or rather, devolution) of the cookbook. In former versions of the “kitchen bible”—those go-to helps every cook has shelved in the kitchen, like Rosso and Lukins’s The New Basics Cookbook—“the tone is chatty, informal, taking for granted that the readers know the old basics: what should be in the kitchen, what kinds of appliances to use, how to handle a knife.” The imagined readers of The New Basics Cookbook have been apprenticed by others, welcomed into culinary traditions, heirs of habits and practices that have been handed down over generations. They bring a know-how they’ve learned elsewhere to the cookbook, they’re not looking for know-how in it.

Gopnik contrasts this with the assumed reader of How to Cook Everything: “Bittman assumes that you have no idea how to chop an onion or boil a potato, much less how chopping differs from slicing or dicing.” So he has to explicitly detail every step, teaching you how to slice with a knife, how to sauté, even how to boil water. So while Bittman’s book does teach you how to cook, Gopnik also notes something sad about this: it’s like learning to speak French from a grammar book rather than having a family to induct you into a mother tongue. It is a way of learning abstracted from any social context, from any history or tradition—unhooked from “the dialogue of generations, the commonality of the family recipe.” As Gopnik puts it:

It’s as if someone wrote a book called How to Play Catch. (“Open your glove so that it faces the person throwing you the ball. As the ball arrives, squeeze the glove shut.”) What it would tell you is not that we have figured out how to play catch but that we must now live in a culture without dads.

How to Cook Everything is a cookbook for a society with culinary amnesia, whose devotion to the supposedly liberating powers of progress and technology has brought us to the point where someone has to instruct us how to boil water. When it looked like the burdens of history and tradition would hobble our confident march into the future, we lopped off our memory, as if tradition was what was holding us back. But now we have to prop ourselves up with mnemonic prosthetics. It turns out forgetting hobbles progress too.

Which makes it tempting to lapse into the sweet sadness of nostalgia—that memory-substitute that remembers only backward, and selectively. Nostalgia is the selective memory of traditionalism. Instead of drawing on the past like a well to nourish our imagination going forward, nostalgia mourns a mythical “golden age” while conveniently forgetting the injustices in that history. Nostalgia invokes “the tradition” as a white knight while deflecting your attention from the serfs crushed underfoot. Nostalgia ends up being its own form of forgetting.

Strung between novelty and nostalgia, a biblical imagination remembers forward. The remembering enjoined by the Torah looks forward to a “time to come” (Deut. 6:20). The biblical command to remember is written in the future tense.

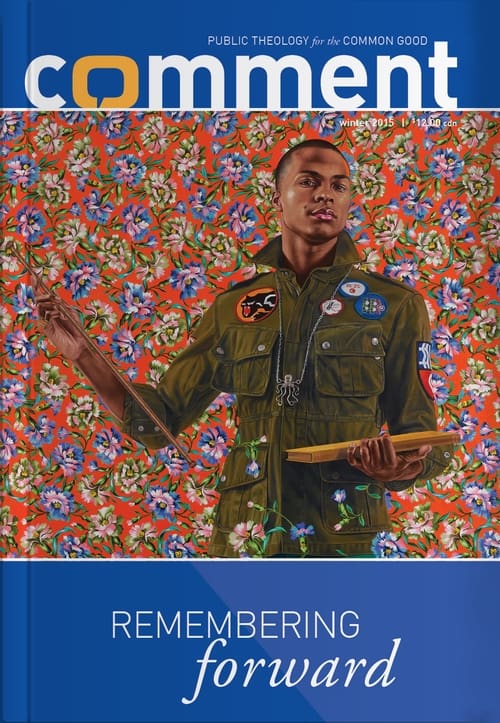

It is this vision of faithful, honest, hopeful memory that we explore in this issue of Comment. We are the thought journal of Cardus, a think tank that is devoted to the renewal of North American social architecture “drawing on more than two thousand years of Christian social thought.” As such, our forward-looking work in the hope of cultural renewal is nourished by a deep sense of memory and the conviction that we still have much to learn from those who have gone before us. Our hope is staked on memory. Those Christians who want to be faithfully present in contemporary society do well to cultivate ancient friendships.

In our age, bent on “progress,” remembering is a revolutionary act—a subversive vote for Chesterton’s “democracy of the dead.” We’re convinced that there are all sorts of buried treasures in our tradition that can be mined for contemporary challenges. Nourishing intellectual water lies in the deep wells of Christian heritage—and yet, all too often, we don’t realize we’re dying of thirst even while slurping up any “new” thing. There are bottles of joy and wisdom and imagination in the Christian cellar that prior generations have abandoned. The goal of this issue of Comment is to unlock that cellar and invite you to taste and see. “Take, eat, remember, believe”: this is the rite of a stretched people who know how to hope because they know how to remember.

However, remembering well always requires overcoming nostalgia—overcoming our selective memories, owning up to our forgetting. Remembering for the future has to face up to what we’ve repressed—shining a light on the shadow side of our traditions. This is why Christians invested in the goodness of creation can’t fall into the trap of Golden Age–ism, because to remember creation is to long for the new creation. There is something inescapably eschatological about Christian remembering.

Willie James Jennings calls us to the hard but hopeful work of remembering in his remarkable book The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race, a work that is a gift precisely because it is a challenge—like Mark Charles’s challenging article on the Doctrine of Discovery in this issue. As Jennings admits, “I anticipate some resistance to the fundamental claim of this work, that Christian social imagination is diseased and disfigured.” A Christianity that hasn’t reckoned with its infection by colonial imaginaries is a Christianity that chooses to forget. Jennings calls us to the difficult work of remembering our complicity so that we can “recognize the grotesque nature of a social performance of Christianity that imagines Christian identity floating above land, landscape, animals, place, and space.” But the reason to do so is to remember a biblical, gospeled vision that is older than this modern hybrid, which makes possible “a Christian act of imagining” that is nothing less than “a compelling new invitation to life together.”

Jennings’s proposal rings with the cadences of biblical memory. The Scriptures, remarkably, canonize lament, heroes of faith are presented with all their tarnish, scoundrels show up in the genealogy of Jesus. This is honest, hopeful memory.

Which is why the church inhabits a different script—one you can see in the season of Christmastide. Since at least the fifth century, just a few days after Christmas, the church has observed the Feast of the Holy Innocents on December 28. Not surprisingly, it’s hard to arrange a furniture clearance sale around this story, so this feast hasn’t made its way into our commercialized Christmas scripts. But that it is embedded in the Nativity narrative, and has been woven into the church’s calendar, is a signal that biblical Christianity is honest about the challenge of evil. After the choir of angels sings about “great joy,” Rachel weeps for her children. Singing “Joy to the World” doesn’t mean we have to paper over the horrors. The Bible doesn’t; why should we? But the good news announced by angels to shepherds turned out to be the incredible news that love conquers death. “He is risen!” is the joyous shout of a people who remember he was buried.