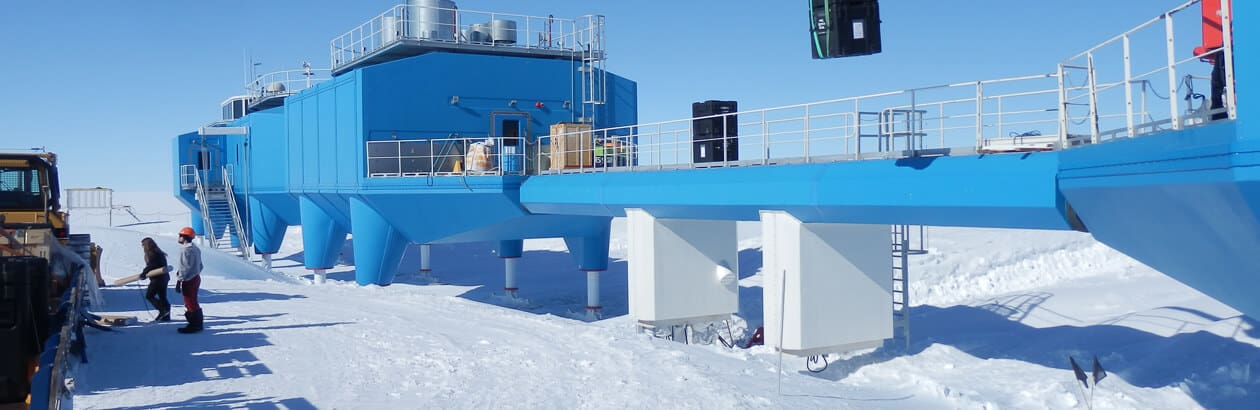

I can think of no better parable for technology and human civilization than the construction of Halley VI, the British Antarctic Survey’s research station planted on the bottom of the world. After the previous five stations were gobbled up by the hungry ice and accumulating snow of the Brunt Ice Shelf, the BAS enlisted Hugh Broughton Architects to design a durable, habitable oasis for work in the frigid desert of the Antarctic. What they dreamed up—and made reality thanks to engineers and contractors—is something you could also imagine seeing on Mars or The Jetsons: a stunning, bright feat of design that combines awareness of the harsh realities of its environment with equally attentive concern for humane living. Resting on telescoping hydraulic skis, the entire station can move across the ice and rise above accumulating snow. But inside, the Robert Falcon Scott module includes pool tables, a TV lounge, and a second-story bar. Enjoying the comforts of a Bristol pub, you could almost forget you’re playing darts on an ice sheet.

In Ruth Slavid’s fascinating book about the project, Ice Station (filled with James Morris’s rather Bauhaus photographs), she gives us a glimpse into Broughton’s thinking. “The team went through a lot of what he considers traditional architectural moves, in other words thinking about how people would interact with space. Thus, at the end of each module the corridor widens in front of the bathroom to facilitate informal interactions as people pass. Each desk contains a flip up mirror so that people can check how they look before joining their colleagues.” (It’s charming to think people still care what they look like when sequestered with the same small group of people in the long darkness of Antarctic winter.)

Perhaps most intriguing is Broughton’s concern to balance comfort and exposure. “Floors are carpeted,” Slavid notes, “and Broughton worked with a colour consultant to ensure that the décor would encourage feelings of calm and comfort. At the same time he felt it was vital to have views of the surroundings and of the sky, as well as a brief outdoor trudge between the two sides of the station, so that people would not become too comfortable and forget where they are.”

The station (and its construction process) are marvels of technological accomplishment, a triumph of human ingenuity in the face of daunting conditions—not unlike the basic human endeavour of making a home amid a cursed garden. Halley VI could be celebrated as a harbinger of humanity’s seemingly unlimited technological power and ingenuity, engendering the sort of self-congratulatory hubris that makes us think we’ll colonize Mars or overcome mortality. Maybe God can build quaint tables in the wilderness (Ps. 78:19), the technological saviour smugly dismisses, but we can build a bar in Antarctica!

But we should note that this sort of confidence in technological prowess does not infect the creator of Halley VI. To the contrary, Broughton thinks it’s important that people not become too comfortable nor “forget where they are.” To my ears, that sounds like an almost biblical caution. Like the human race, Halley VI is suspended between a remarkable endeavour and an inescapable vulnerability: have dominion over the earth, and remember you are but dust. This issue of Comment invites you to think in this space.

These are not new questions, even if they take on a new shine in the age of pixels and SpaceX. Technology is as old as Eden. Tools for tilling the garden were anticipations of quill pens and steam engines and the smartphone in your pocket. The first “hack” was a needle that sewed together Adam and Eve’s fig leaves. We are called to shape and form worlds. So it’s not a question of whether we’ll employ technology in our cultural labour; the only interesting question is how.

But these worlds also shape and form us. Technology is never just an instrument we use; it also uses us. As James Poulos points out in a recent National Affairs essay, “Technology and Political Theory,”

Although the ongoing revolution conjures up visions of even more staggering achievements, these do not require the imaginative leaps that took us from the telegram to the internet, or from the home phone to the smart phone. Today, the real surprises in store are not about what technology can do for us, but what technology is doing to us. Recognizing this makes us better suited to grasp the meaning of the revolution we are living through.

This issue of Comment hopes to do some of that work of grasping the revolution we’re living through. That means taking responsibility for the worlds we make that, in turn, make us. Whether technology inspires or worries us, it is never an “it,” out there: it is not a god who descends nor a “rough beast” that slouches toward us from parts unknown. It is an idol or monster of our making.

Or it can be a gift created in response to a call to love our neighbours and unfurl creation’s potential. The question behind the “question concerning technology,” as Heidegger put it, is really a more fundamental question: What do we want? What sort of a world do we want to create? And how do we become the kind of people who want the right things?

Those are the sorts of questions we’re asking. We’ve convened a conversation that considers technological innovation and its future as it intersects with various realms of work and culture. In a playful gambit, we’ve organized this issue around the revolutionary yet enduring technology of Gutenberg: the book. Riffing on important recent books, you’ll read Albert Borgmann on mortality in “the fourth dimension,” Noah Toly on “smart cities,” and a multidisciplinary symposium on the provocative new book by Richard Susskind and Daniel Susskind, The Future of the Professions: How Technology Will Transform the Work of Experts. And you won’t want to miss my interview with Peter Thiel, cofounder of PayPal, doyen of Silicon Valley, and author of the innovators’ bible, Zero to One—a veritable claim to human creation ex nihilo. As you can imagine, we had a lot to talk about.

So in this issue of Comment, we consider how technology is being deployed in different spheres of society and different professions that serve the common good. Our goal is to identify the technologies we take for granted as if they were “natural,” critically consider whether and how they shape our common life, and imagine possibilities of reform and renewal.

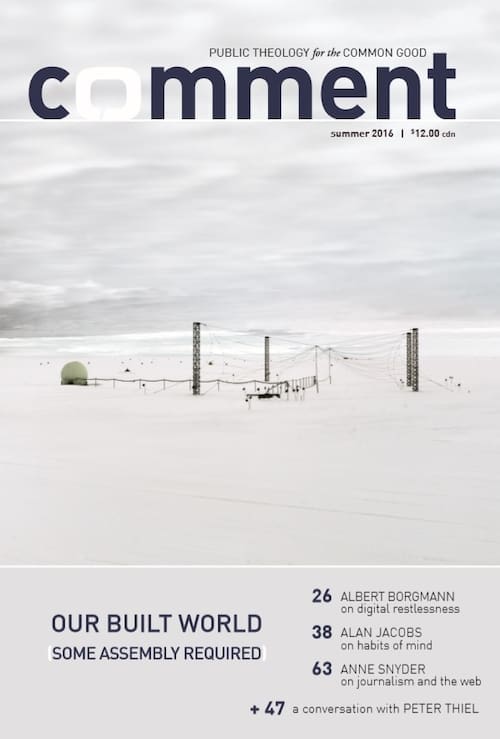

On the cover of this issue is another photo from Halley VI. It’s a stark image of the communications installation in the midst of the bleakness of terrain that dissolves into sky—a visual anchor in what might otherwise induce vertigo. You can feel the tenuousness of these towers and lines when you imagine howling winds and pelting ice. And yet there they stand, a human layer of creation that exhibits the remarkable image-bearing capacity of humanity. It’s no wonder we’re tempted to imagine ourselves gods. It’s why Broughton’s architecture pushes the scientists outside: to remember where they are, and what they are—creator and creature, ingenuous and vulnerable, heroic and mortal, inspired and embodied.