For a boy growing up in Ontario, it was never a question: you’re going to play hockey. Though Embro was a village of only 600 people at the time, we had a new arena, a robust minor hockey system, and a long legacy of the sport encoded in our civic DNA. So at four years old, we all moved from the pond to the ice pad, donning the purple hockey sweaters that many of us wore until we were twenty.

This was also part of something bigger. You could count on neighbouring villages like Drumbo and Plattesville and St. George having minor hockey systems, all webbed together by the OMHA.

When you’re ten years old, you think this is just part of the furniture of the cosmos; something given, natural, and taken for granted—that Saturday morning clinics and Tuesday night practices are just part of the rhythm of the universe, as if when God said, “Let there be light,” the big klieg lights in the rafters of the arena also came on. You never really think about what sustains all this, and if you do, you just imagine some anonymous “them” holds it all together, a vague, distant “they” who are responsible for all of this.

But when you’re an adult you realize: this doesn’t just happen. That something as mundane and yet enduring as Embro minor hockey is not a given; it is an institution. It is only because it is sustained by communities. It is bigger than the people who inhabit it, but it also depends on the people who embody it. The “they” you never saw in your youth turn out to just be people like you who have taken the reins and taken ownership. We could only take minor hockey for granted because, in fact, each generation received it anew, owning it, tending it, reforming it, and passing it on to the next generation.

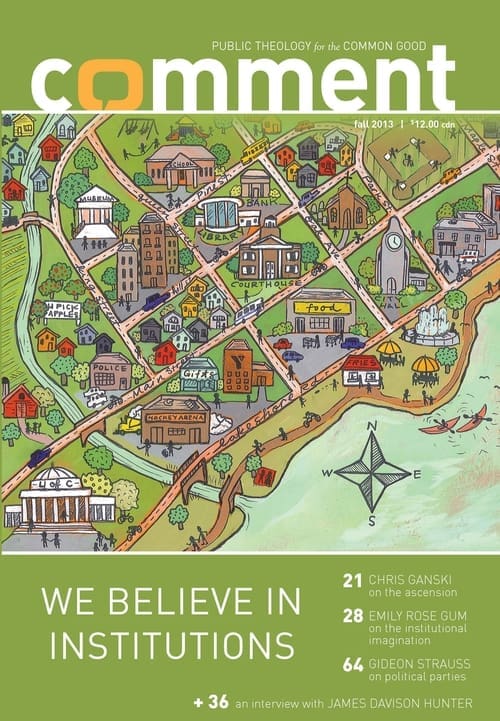

In this issue of Comment we proudly profess that we believe in institutions. It is part of our creed. The lilt of this profession carries echoes of The Creed in which we profess, “I believe in the holy, catholic church.” But that’s not the only institution we believe in. We also believe in institutions like Embro minor hockey, the Hamilton Public Library, the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, Surrey Christian School, the Calgary Planning Commission, the United States Congress, and that quiet but powerful culture-making institution that is the family.

In a cynical age that tends to glorify “startups” and celebrate anti-institutional suspicion, faith in institutions will sound dated, stodgy, old-fashioned, even (gasp) “conservative.” So Christians who are eager to be progressive, hip, relevant, and creative tend to buy into such anti-institutionalism, thus mirroring and mimicking wider cultural trends (which, ironically, are often parasitic upon institutions!).

And yet those same Christians are rightly concerned about “the common good.” They are newly convinced that the Gospel has implications for all of life and that being a Christian should mean something for this world. Jesus calls us not only to ensure our own salvation in some privatized religious ghetto; he calls us to seek the welfare of the city and its inhabitants all around us. We love God by loving our neighbours; we glorify God by caring for the poor; we exhibit the goodness of God by promoting the common good.

But here’s the thing: if you’re really passionate about fostering the common good, then you should resist anti-institutionalism. Because institutions are ways to love our neighbours. Institutions are durable, concrete structures that—when functioning well—cultivate all of creation’s potential toward what God desires: shalom, peace, goodness, justice, flourishing, delight. Institutions are the way we get a handle on concrete realities and address different aspects of creaturely existence. Institutions will sometimes be scaffolds to support the weak; sometimes they function as fences to protect the vulnerable; in other cases, institutions are the springboards that enable us to pursue new innovation. Even though they can become corrupt and stand in need of reform, institutions themselves are not the enemy.

Indeed, injustice is often bound up with the erosion of societal institutions. For example, Nicholas Kristof’s reporting from Africa constantly observes that tyrants and warlords flourish precisely in those places where their rogue armies are the only durable institutions, preying upon the absence of any other institutions that might resist.

The destruction of institutions actually makes room for injustice. You might say that the devil also believes in institutions, which is precisely why his minions are often so deviously patient and persistent in their goal of eroding them. You can imagine Screwtape writing to Wormwood with a key piece of advice: “Evil triumphs in just such a vacuum, so patiently chip away at the institutions of civil society. We’ll reap the rewards later.”

So we believe in institutions because we oppose injustice. But we fundamentally believe in institutions because we believe in the Scriptures and the cultural commission given to humanity in the Garden. To be fruitful and multiply is to begin—and inherit—the institution of the family. To cultivate creation is to fill the earth with institutional life that was begging to be unfurled—in museums and schools, in legislatures and libraries, in universities and unions. Institutions are durable, communal ways that we can act in concert with our neighbours to achieve penultimate goods. So instead of thinking about institutions as big, hulking, static behemoths, think of institutions as dynamic, social enactments. Try to imagine “institutions” as spheres of action. Institutions are not just something that we build; they’re something that we do.

Institutions are strange realities. On the one hand, they are bigger than us. They are bigger than individuals, certainly, but they are even bigger than any particular group or generation. They endure. We inherit them. Institutions are the sorts of social realities that come before us, that are part of the environment we take for granted. Even though institutions were founded (“instituted”) at some point, many institutions are now so woven into our world that it’s hard for us to imagine a world without them. These cultural products seem as natural as rivers and as old as mountains.

On the other hand, institutions can’t live without us. They are bigger than us, but they also need us. The only survive and endure if each subsequent generation receives them, tends them, and sustains them. And at some point, we have to recognize: we are that generation.

I recently overheard a commentator on National Public Radio observe, “In the history of the world, no one ever washed a rental car.” What he meant was simply that we don’t care for what we don’t take ownership of. Growing up—becoming an adult—is recognizing that the institutions you take for granted actually depend on you. There’s no “them” out there other than (people like) you. All of the folks on the local school board or church council or Little League committee are people just like you who have taken ownership of the institutions that they inherit, recognizing their indebtedness to them and wanting to bless others through them. These institutions are channels of blessing for the common good and to devote oneself to their welfare is to seek the welfare of the city.