Y

Your life is in your throat: the substances of life—breath, water, and food—pass through it constantly. So, it’s an intimate horror when cancer grows in your throat. Sometime on July 2, 2020, a tumour broke through the tissue at the base of my tongue. I was diagnosed with throat cancer in an emergency department at 3:00 a.m. on July 3, 2020.

Suffering and death’s approach will change your life. Projects that define your life become pointless, while actions you once performed as if half asleep suddenly disclose meanings you have no words for. Cancer transformed how I understood love and, with it, how I experienced the Eucharist.

If you had asked who I was before cancer, I would have answered with a list. I was a husband and father of five, a child psychologist, a statistician, a researcher, a medical school professor, and a Christian. But that’s too much and too little. A Buddhist teacher once told me that “you are what you worship,” by which she meant that worship is “what engages you and that to which you are devoted.”

What did I worship? My mother raised me in the church, and as a child of the 1960s, I was catechized by Protestants committed to Martin Luther King Jr. and justice. They didn’t speak of hell. God was mentioned frequently, so contrary to rumour, he wasn’t dead but didn’t seem to be gainfully employed. I internalized that view.

Suffering and death’s approach will change your life. Projects that define your life become pointless, while actions you once performed as if half asleep suddenly disclose meanings you have no words for.

I did well in school and entered Harvard, hoping to find a vocation. I failed to find one. Harvard consecrates you in the meritocracy: my classmates expected to serve the Pax Americana and, through jobs in government, law, or finance, to rule the world. I couldn’t. Alasdair MacIntyre wrote that

a crucial turning point in [the] earlier history [of the West] occurred when men and women of good will turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that imperium.

The Pax Americana of my childhood was a world of burning cities, napalmed children, and martyrs murdered by death squads. I graduated in 1976 and worked as a child-care worker for institutionalized mentally ill children. After several years of minimum-wage mental health work, I had a vocation: these children mattered. Unfortunately, our treatments weren’t helping them. Child psychotherapy in the seventies was dominated by charismatic charlatans. I started graduate training in psychology and statistics. I joined the effort to make psychology and psychiatry into empirical sciences, with methods for caring for sick children that worked.

Research is competitive—many are called, few are chosen—and you must do it well or not at all. I came to a view about how best to accomplish this: do things the hard way. I cultivated fortitude and cognitive virtues: rationality, open-mindedness, integrity, and perseverance. I threw myself at challenges with objective criteria for success—publishing in highly selective scientific journals, mountaineering, triathlons—tests where you can fail because that’s how you learn. Nietzsche got this perfectly in Beyond Good and Evil:

The discipline of suffering, of great suffering—do you not know that only this discipline has created all enhancements of man so far? That tension of the soul in unhappiness which cultivates its strength, its shudders face to face with great ruin, its inventiveness and courage in enduring, persevering, interpreting, and exploiting suffering . . . —was it not granted to it through suffering?

I’ve learned that I was mistaken in thinking that the stress of the hard way was great suffering; thank you, cancer. Nevertheless, these pursuits forged me as an agent, someone who could do things.

So, what did I worship? The strenuous pursuit of scientific excellence. And I valued the pursuit of excellence as highly as its achievement.

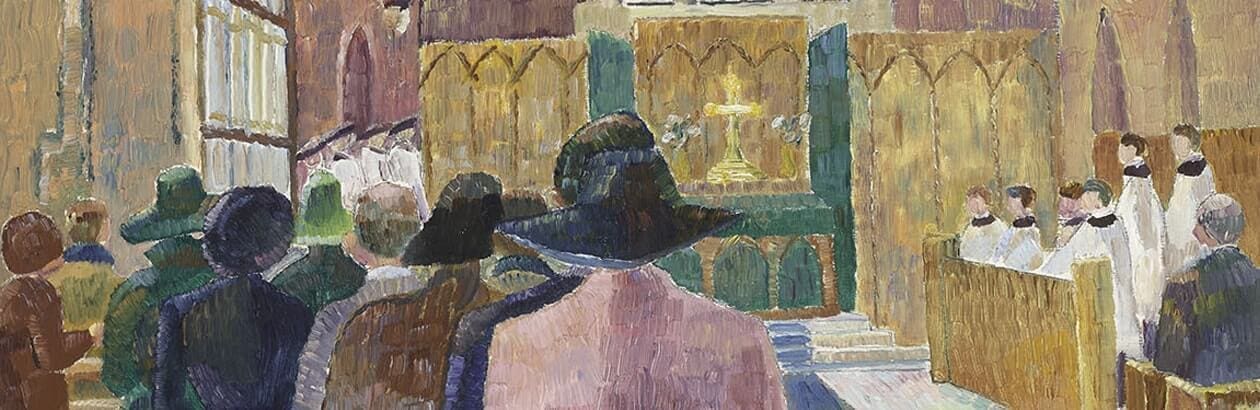

But didn’t I worship God at church? I believed in God because, Deo gratias, I had experienced God’s direct presence during a crisis in my youth. Still, my empiricism required that I keep my distance from him. I was a churchgoing Anglican because I loved ancient English choral music and the Book of Common Prayer, but I prayed only when the liturgy required it. The Eucharist was a curious ritual. The symbolism was apt because the hospitality of Jesus’s table fellowship with all, sinners included, captured the egalitarian justice I longed for, a community without distinctions of rank. But it was just a memorial of the martyrdom of Jesus. I wasn’t worshipping in the Buddhist teacher’s sense of deep engagement.

I began radiation treatment soon after I was diagnosed. Radiotherapy put me in a machine that focused X-ray beams on the tumour at the base of my tongue to burn it to death. However, the X-rays also extensively damaged the healthy tissue outside the focus. My throat pain increased as treatment progressed. I lost my ability to taste, then my ability to swallow. I had to feed and drink from a hanging bag, through a tube that snaked into my nose, through my sinus cavity, and past the tumour down my throat.

I’m in a field where projects take years. Cancer laughed: “Do you even have one year?”

Cancer humbled me, breaking the foci of my identity. Nietzschean struggle won’t cure cancer. Yes, the body is linked closely to the mind. Unfortunately, there’s little evidence that your attitudes can affect tumour growth. (Your attitudes matter, however, for how you will live, given you have cancer.) My status in the hospital changed. At work, I wore a badge on a lanyard, a talisman with my degrees and the title “Professor,” a meritocratic coat of arms and a reminder that I am here for science. It’s the others who are here because their bodies are growing masses that may kill them. After the diagnosis, however, I was no longer “Dr. Gardner”; I was “Mr.” like any other patient. The diagnosis had converted me from an agent to a patient. (“Patient” derives from a Latin word that means “to suffer or endure.”) Cancer also limited my ability to do science. I’m in a field where projects take years. Cancer laughed: “Do you even have one year?”

What can patients hope for; what can power us out of despair? Cancer patients kill themselves at many times the rate of matched peers. I have lost a close friend to suicide following a cancer diagnosis, and I recently learned of a school friend who jumped from his building.

But in any situation, there are opportunities to serve. When word spread that I had late-stage cancer, many friends asked for Zoom calls. (These were the early days of Covid.) At first, these meetings were uncomfortable; I am an introvert and don’t want things to be about me. Yet I saw that many virtual visitors suffered because they didn’t want to lose me, and cancer frightened them. I began working on being a “good listener” who focused his attention on the other.

Valuing another’s suffering as highly as you value your own, and engaging with them, is an act of love.

Simone Weil, however, said that being a “good listener” isn’t enough. To find the other, you must suppress your concern with your self-presentation and suspend your emotional self-protection from the other’s suffering. Otherwise, good listening is performative. This profound shift of attention from yourself to another can open you to respond compassionately. Direct experience of another’s suffering transfixes you, which can hurt, and you can flee or engage. Valuing another’s suffering as highly as you value your own, and engaging with them, is an act of love. It recognizes—and communicates—the other’s value as a person.

I had thirty-five radiation sessions over two months, and the flesh in my throat smoldered for weeks after the treatments ended. But after a while, I could swallow food, and later my ability to taste returned, at least in part. I resumed daily yoga and exercise-bike workouts. My throat stopped hurting. I was getting better.

That didn’t last. In the winter of 2021, my throat pain returned. A surgeon did a biopsy. The tumour was back and, just months after treatment, growing. The survival chances for someone with recurrent throat cancer are much worse than the odds for someone with newly diagnosed cancer. The surgeon gave me a prognosis of “months, not years.” He offered me palliative care or medical assistance in dying (MAID); he believed there were no other realistic treatment choices. I refused MAID “for religious reasons.”

But believing that it would be wrong to kill myself is not the same as being able to say why I want to continue living. What can I hope for when there is no cure?

I can hope to know God. Aquinas taught that union with God is the most perfect human happiness and the ultimate goal of human life. But union how? I began a practice of daily prayer and lectio divina, prayerful Scripture reading. I applied Weilian attention to listening for God and discovered I could vividly hear the evangelists and apostles responding to God’s presence. One Sunday, however, soon after our parish reopened from Covid, I was the lector, the layperson reading one of the Scripture portions. I read St. Paul, “Don’t you know that all of us who were baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death?” (Romans 6:3).

I believed that, in a sense I couldn’t explain, Christ was present in the Eucharist, and I was joining his life by taking Communion. But what does it mean to be baptized into Christ’s death? How can you join that?

Despite the surgeon’s view that there were no treatments, I got access to a new immunotherapeutic drug, pembrolizumab. I started getting infusions every three weeks. There were side effects, but I was clearly doing better in a couple of months.

So began a happy time. Covid travel restrictions were lifted, and we could spend time with family and friends. I started to triage my remaining scientific projects, focusing on completing those that presented my ideas for improving the child and adolescent mental health system.

On Pentecost 2022, I was struck that many members of my family were all at the same service, albeit in churches across the continent. When priests utter Jesus’s words instituting the Eucharist (quoting, for example, Mark 14:22, “Jesus took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, ‘Take it; this is my body’”), we all heard Jesus. Heard him where? Christians gather at different altars, but if Christ is the high priest presiding at the Eucharist, we are all at the same altar, joining our voices with angels and archangels and sharing one communion with all Christians across the globe. And when is the Eucharist happening? God created time and is outside the temporal framework of the universe. God’s knowledge and action encompass all points of time simultaneously. Hence, all past, present, and future events are simultaneously present to Christ. Every local Eucharist connects to the one on Holy Thursday in the upper room, where Jesus ate with his disciples. The Eucharist is more than a ritual of remembrance: We are all at that table.

Believing that it would be wrong to kill myself is not the same as being able to say why I want to continue living. What can I hope for when there is no cure?

The good times with pembrolizumab lasted only eighteen months. I began experiencing increasing throat pain, coughing, and swelling of my mouth and tongue. On April 13, my wife and I met with my radiation oncologist. He used a long, thin, flexible cable with a tiny video camera and an LED at one end. The other end was plugged into a large video monitor. He inserted the cable into my nostril, pushed it through my sinus passage, and down my throat. It’s not as difficult as it sounds.

What we saw was horror.

A large, irregular grey mass covered the root of my tongue, as if a vast fungus had colonized the back of my mouth. We were silent; no one expected this. I said, “What is that?” My wife, a physician, answered: “Necrotic throat tissue, killed by the tumour.” The cancer was growing again. Immunotherapy was no longer working, and my medical oncologist discontinued it. I’m now on palliative chemotherapy. That means there are no reasonable hopes for a cure, but it may be possible to slow disease progression. Every three weeks, I spend six hours connected to intravenous pumps getting a cocktail of carboplatin and paclitaxel. Nothing about my future is inevitable, but my oncologist is reluctant to speak of more than a year.

I began looking for saints, people who had endured great suffering through their relationship with Jesus. Bonhoeffer was one, another was Fr. Pedro Arrupe, SJ, the former secretary general of the Jesuits. In December 1941, while serving as a missionary in Japan, he was arrested by Japanese security forces and placed in solitary confinement for thirty-three days. Each day he expected to be executed. After release, he served in Hiroshima. On August 6, 1945, he was near ground zero, but was spared because a small hill shielded the mission house from the direct blast. A former physician, he rushed into the devastation and was among the first of first responders.

Arrupe got through these experiences by companionship with Jesus in hours of daily prayer. He wrote that “nothing is more practical than finding God, that is, than falling in love in a quite absolute, final way. What you are in love with, what seizes your imagination, will affect everything. . . . Fall in love, stay in love, and it will decide everything.”

Like many Jesuits, Arrupe had a special devotion to the Sacred Heart, including prayers in which you visualized Jesus’s heart and the love it contains. The image of the Sacred Heart, on fire and pierced by a spear, had always repelled me as Catholic kitsch. Yes, Jesus is God incarnate, but that incarnate?

Cancer, however, is that incarnate. You think about what the moment of death will be like. Will I be starved for oxygen, breathing in agonal gasps, crushed by chest pain? One of the attractions of physician-assisted death is that you can escape that. Conversely, if you are committed to living with cancer, you must prepare yourself for dying. I began a practice of preparing myself for Eucharist by prayers devoted to the Sacred Heart.

The Eucharist gathers all of us at the foot of the cross, but it’s more than a fellowship meal. We’re watching a man dying in torture. Why this agony? God knows everything across time and space. Since God is compassionate, he experiences all the suffering of creation. I don’t understand why creation must suffer. My guess is that there are mathematical constraints such that living systems must be built by evolution, with the suffering that entails. Mathematics is outside creation—God cannot make 2 + 2 = 5—so these constraints make suffering an inescapable cost of life. Luther wrote that the cross reveals that our God is a suffering God, and his constant renewal of what exists is a continual mounting of the cross. So life requires the acceptance of some—not all!—suffering and death, until the construction is finished.

I began using the Sacred Heart to visualize Jesus’s suffering: the shock when hard men pounded spikes into his wrists, the acceleration of his heartbeat when the collapsing of his lungs deprived him of oxygen, and the piercing of the spear after his death.

But there is a dual space here: each moment of suffering maps to an act of love. God created time, space, and matter knowing what it would cost him. He knows each sentient creature’s suffering; each point in suffering space maps to a specific intention of love for that creature. Gathered beneath the cross, we witness infinite suffering and endless love. When the Sacred Heart is pierced, water and blood flow out. It is suffering and life, caught in a chalice and given to me.

Receiving this outpouring of love, I fall forward into the moment, the way the lily bends forward in the breeze (Matthew 6:28). It’s the falling of Mary in response to Gabriel’s news in Botticelli’s Cestello Annunciation, as if she had been shaken by a gravitational wave through space-time. Cancer showed me a door that is always open, a path that we can always follow; we can always yield ourselves to the call to love creation and its creatures. What love will require can’t be fully specified in advance: that’s the point of Weilian attention. But if Christ experienced my suffering to give me life, how can I reject the call in good faith? From the view of eternity, he has already been through what’s ahead of me. There’s no trick to offering my suffering to Christ; he has it already. I’m simply joining him and his community of disciples. I can offer my death and suffering by living out the time in faith, hope, and love, in union with Christ’s sacrifice, and in this small way participate in his redemptive work.

This is the baptism into Christ’s death. It doesn’t mean my suffering is comparable to or replaces Christ’s. But through wholehearted acceptance of providence, I am sharing in the sacrifice he has already made. Benedict XVI defined worship as the right way to relate to God, which is the right way to live in the world. The right way to connect to God is to fall in love. It’s a different way of being. Proper worship lets light from heaven fall into our minds and gives us a taste of a perfect future.

Near the end of his life, Arrupe suffered a stroke and was unable to continue leading the Jesuits. In his last statement to his Jesuit brothers, he said, “More than ever, I find myself in the hands of God. This is what I have wanted all my life from my youth. But now there is a difference; the initiative is entirely with God. It is indeed a profound spiritual experience to know and feel myself so totally in God’s hands.”

July 23, 2023. I am on the kneeler in a pew, praying before the service of Holy Eucharist. It used to be a sung Eucharist. I miss that. I have a crucifix cupped in my hand. I visualize the Sacred Heart of the man dying on the cross, the heart of the second person of the Trinity, the heart of God, and of the Holy Spirit. In my hand, pressed against my chest.

St. Paul contrasts the spirit and the flesh. We moderns misread this psychologically, as Paul’s report of how his superego cannot rule his desires. We miss Paul’s deeper point. We are spirits transfixed by what’s happening to our flesh at this moment, enslaved by worries about our daily bread, outside Christ, and estranged from God. As if under a spell, we cannot understand what being in Christ could mean.

This morning, on my knees, I am not that slave; I am freed from that spell. Think it through. Christ called me to serve him in others. Jesus said I will meet him in the prisoner and the homeless person. This hardly seems credible because if I can serve others in Christ, then others can serve Christ in me. That could happen only if, shockingly, Christ is in me. Right. Now.

Time stops. I am in the Heart cupped within my hand, pressed against my chest, baptized into his death and his love. The Sacred Heart is his heart—my authentic heart—already dwelling within me through the Holy Spirit. It is your authentic heart. We are all here, already in Christ. The heart of the universe, cupped in my hand.