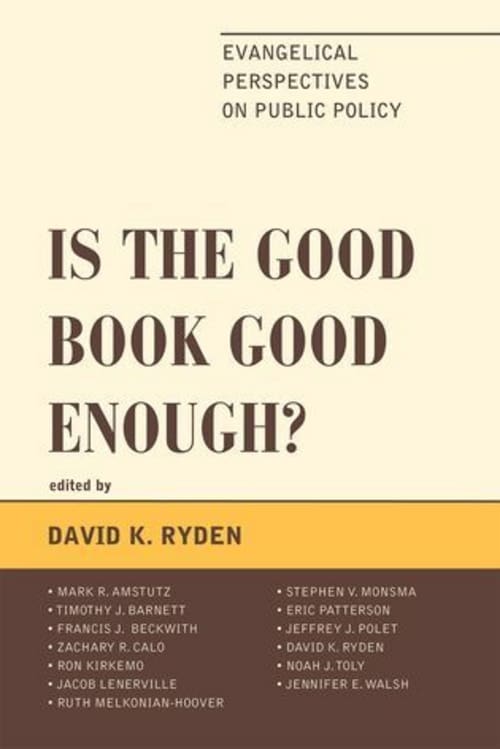

The evangelical political mind is . . . changing. That is the intriguing story told by a newly published collection of research essays on evangelical public policy and activism: Is the Good Book Good Enough? Edited by David Ryden, professor of political science at Hope College, the book convenes fifteen scholars—mostly political scientists—to explore and evaluate how evangelicals in the United States think about and do public policy. The book serves simultaneously as a mirror held up to the evangelical movement, a critique, and an excellent primer for those seeking to understand the history and current state of evangelical contributions to public policy.

The chapters survey recent evangelical engagement in a wide range of areas: the environmental movement, social welfare, criminal justice, immigration, racial reconciliation, economic policy, the same-sex marriage debate, national security, human rights and humanitarian intervention, and foreign policy. After examining developments in all of these arenas, the authors pose a fundamental question for evangelicals involved in politics and public policy (and for citizens in general). It is an especially significant question for the next generation of evangelicals and emerging Christian leaders. The evangelical political mind may be changing, but is it maturing?

The signs of change are difficult to deny. Evangelicals in the U.S. have expanded the range of issues on their agenda. They can no longer be fairly stereotyped as belligerent culture warriors with only a single-issue or double-issue focus on abortion or gay rights, for example. Decades of discussion and debate about the Christian worldview’s relevance to every area of life and the Bible’s mandate to do justice may just be beginning to bear some very good fruit. American evangelicals are recovering an intuition that politics can advance justice, although many continue to hold to a far more suspicious and skeptical view of government than their counterparts in other countries.

Of course, not all evangelicals think alike. Stephen Monsma contributes an excellent chapter on the history and current challenges of the American social welfare system. In it, he charts out an evangelical view on poverty and justice that advocates a limited role for government while also affirming a robust role for the state to protect the vulnerable in partnership with civil society institutions, including faith-based organizations. His more nuanced public policy proposals show that some evangelicals have been hard at work developing alternative approaches to statecraft that fit neither the libertarian nor “big government” models.

However, the book describes how, over the years, many negative examples of Christian engagement have tarred all forms of Christian politics with a certain guilt by association. This has at times marginalized the insights and action of those evangelicals who marched to a decidedly different drumbeat than that of the Christian Coalition, Pat Robertson, or Sarah Palin—or whoever the increasingly secular public mind may temporarily select as the Christian ogre of the month, intent on subverting the separation of church and state and establishing a theocracy.

The evangelical students of 2011 on Christian and secular university campuses inherit this very polarized and secularized context. They are seeking and discovering new ways to engage faithfully. They are finding their voice and elevating public policy concerns that range from climate change to global poverty to sex trafficking to state-sanctioned torture.

They also no longer fit the profile or media stereotype of the conventional religious conservative. If, as Jim Wallis has provocatively said, “the monologue of the religious right is over,” then it is reasonable to ask, what comes next? The book’s authors hint at—but unfortunately do not develop the case systematically—that the answer may not be the development of a stronger religious left, but instead the emergence of a new “evangelical center” in search of “a broader policy framework around which evangelicals might coalesce.”

College students and recent graduates are not the only ones broadening the evangelical policy agenda. Established evangelical public policy and advocacy organizations such as the National Association for Evangelicals, World Vision, Evangelicals for Social Action, the Center for Public Justice, and International Justice Mission are leading the charge too. In fairness, many evangelicals in public policy and many engaged citizens have been hard at work for decades crafting such an agenda and praying for such a moment as this. However, their efforts have received far less media attention for a variety of reasons, and are only now being discovered.

It is regrettable, in fact, that this volume gives scant attention to the important labours of many evangelicals in developing the kind of alternative intellectual framework that the authors repeatedly note has been lacking in most evangelical political advocacy. In fact, in Ryden’s final chapter one might be led to conclude erroneously that evangelicals today have no tradition of serious political reflection to turn to when new opportunities for influence arise. He asks, “If evangelicalism can be seen as a semi-coherent discernible policy perspective, what are its defining traits? The short answer to the question is that there is no comprehensive evangelical policy framework to be found, at least in the sense of a perspective akin to liberalism or conservatism . . . “

But that does not necessarily mean that no such perspective exists or could be developed. If an evangelical political mind in the U.S. has been quietly maturing out of the spotlight, it is thanks to the dedicated work of a minority of evangelicals who have never felt entirely at home with many of the political or public policy options on offer in either the conservative or liberal camps, as they have tried to influence politics-as-usual in Washington or through state or local governments. They have also left a long paper trail of research and writing on the role of the state and a Christian theory of society and justice. This intellectual spadework could inform the advocacy of the newly mobilized evangelical activists described by Ryden, who are rightly dissatisfied with the status quo and are seeking to build a new “evangelical centre.”

They could consider as well international sources of Protestant Christian reflection and activism that the book does not reference. A quick glance at web pages of various Christian democratic movements shows there is much insight to be gained from sources that the U.S. evangelical movement has yet to engage seriously. The experience of established Christian political parties, leaders, and think tanks such as those associated with the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) and the Christen Unie (CU) in the Netherlands offer important lessons in Christian public policy formation and governing. See, for example, the Standpoints document of the Christen Unie or the resources at the CDA’s website for a quick overview. Their profile reflects an orientation to a type of “new evangelical center” that many evangelical activists and scholars in the U.S. are seeking. These parties and initiatives differ significantly from both the American Democratic and Republican parties, in that their policy platforms and proposals do not remain confined within the traditional conservative/liberal constraints most American evangelicals have come to expect. These resources can equip evangelical policy makers with the insights and strategies and principled policies required for building effective coalitions with Roman Catholic, Jewish, and other voters who desire government policies that advance justice on a broad range of specific issues up for debate in public life and on Capitol Hill.

The book’s main critique accurately portrays how much evangelical political thinking and action has rested on poorly thought out foundations or approaches that are arguably in conflict or direct opposition to biblical principles. Ryden warns evangelicals of today to avoid the mistakes of past generations who were co-opted into the service of ideologies, political party platforms, and excessive partisanship untrue to their faith that stunted the development of a more consistent Christian political witness. In their proper rejection of reactionary postures and policies of the religious right, Ryden argues, younger evangelicals and other leaders should also guard against their own cultural capitulation and a too quick accommodation or “subordination of theologically grounded thought and action to the dominant values and ethos of the broader secular culture.” In becoming so at home within the broader culture and adept at a less confrontational style, new evangelical elites may lose the prophetic edge that some take pride in recently reclaiming. Ryden explains, “The danger is that they never take an adversarial stance to the culture. The confluence of Christianity and culture carries with it the temptation to dilute stances considered controversial or retrograde by the broader secular culture, lest one risk its antagonism or derision.”

This is a particular risk if evangelicals do not do the hard work of grounding their more comprehensive policy agenda in an equally comprehensive Christian political philosophy or principled framework. He concludes:

The danger is that policy positions are derived not from intellectual or doctrinal roots, but from intuition, warm sentiments, and a desire for validation for embracing what is enlightened by today’s secular culture. Unless evangelicals can arrive at a theologically grounded set of reasons for pursuing the new set of issues, they will be no more reflective of God’s presence in the world than those obsessed with single-issue politics. It is simply trading in one form of co-optation for another, exchanging the lure of party or ideology for the approval of the secular world.

In his chapter describing the emergence of evangelicals as “the new internationalists” defending human rights on the international stage, Zachary Calo issues a similar challenge to evangelicals to seek out solid principled grounding for their new and increasingly lauded activism. This will be a key step in the maturing process. Calo explains, “The recent explosion of evangelical activity on behalf of human rights issues has largely focused on political organization, activism and institution building. Evangelicals have given far less attention to intellectual and theological reflection on the issue of human rights and the role of the church in global politics more generally.”

One mark of maturing would be for evangelicals to cast off the populist anti-intellectualism and oversimplified approaches that have often hobbled the movement. Some authors see the beginnings of a new model taking hold that instead reflects a high regard for the life of the mind and Christian and secular scholarship in the service of the public good. Calo concludes:

A significant challenge confronting the evangelical church as it moves forward will be to develop an account of human rights informed by both the Christian theological tradition and broader intellectual currents in politics, law and philosophy. Theory and practice must unite if the evangelical human rights movement is to emerge as culture forming movement.

The authors conclude that it may be too early to tell whether the changing evangelical political movement reflects a maturing political mind. However, they make a convincing case that this moment presents remarkable opportunities to shape the movement’s future direction.

To that end, the book prompts a few action items to consider from one’s own position of influence. Now may be the time for new cross-border (US-Canada) and other international partnerships between Christians engaged in public policy. We have much to learn from one another’s different (yet similar) political challenges. The views, goals, and strategies of American evangelicals may not be as different from their peers in other countries as has sometimes been assumed.

The Good Book also suggests repeatedly that evangelicals in politics could benefit from a sharper, more focused political-philosophical framework. Resources are out there, but connections need to be made.

Finally, Christian public policy practitioners should reflect and strategize together about how they can act now to build a more mature Christian political mind and movement over the next thirty years. It is not an overnight task. It is the work of generations. St. Paul grasped something of this when reminding his flock that God was at work in them and through them. God can do infinitely more than we can ask or imagine—even in politics.