When it comes to the quest for wisdom, few intellectuals living today have the gravitas of Leon Kass. A physician, a scientist, a humanist, and an educator, his writing has been singular, his teaching legendary, and his fifty-four-year marriage to the late Amy Kass a witness to the generative power of two becoming one. Since her death in 2015, he has lived for extended periods in Jerusalem, where a group of Jewish scholars from Shalem College became his friends and study partners, meeting regularly with Kass to ponder the book of Exodus and mine its riches. While Kass had been teaching the book for fifteen years at the University of Chicago, it was these conversations in Israel, the relationships encircling thought, that began shifting Kass’s relationship to the text. What does it really mean to be called a kingdom of priests and a holy nation? What does it mean to be God’s gift to the larger world? What follows is an exploration of these questions past and present, from one who’s studied them deeply, and found himself changed.

—The Editors

Anne Snyder: Why does formation of a people matter? Why should we learn about the ways and means of forging coherence and, eventually, national identity?

Leon Kass: English has two words that we often use interchangeably, “people” and “nation.” The root of the meaning of “nation” is people who have common descent from a common ancestor. They are somehow biologically related. But a “people” is defined in terms of a common history, common mores, common songs, stories, culture, a common way of life, common aspirations.

We live in a world in which many of the old nations, particularly in Europe, can’t decide whether they want to be a people at all.

But even in the United States, the question of what makes the United States a people is now a contested question. There’s a great deal of difficulty if people don’t have something deeply in common that can hold them together amid all of the political and cultural struggles that inevitably arise in a democracy.

AS: You talk at the beginning of this book about coming to see, through your reading of Exodus, that it’s impossible for there to be an enduring, thriving people without a communal story, shared moral norms, or common national aspirations. When those things die, eventually the people or the civilization dies. How might you talk about those three ingredients in the US today?

LK: I’m really quite worried about us, on all three counts. I grew up in the immediate postwar period, and it was a wonderful time to be an American—partly because of what we had achieved in the war. One could feel good about the country that it lent its weight, power, blood, and treasure to fighting perhaps the most barbaric and cruel despotism the world has seen. And it stayed the course and held the line against Stalinism. Opportunities were open for immigrants and children of immigrants like myself to go forth and make of yourself what you can.

Yes, there were struggles, including the civil rights struggle, which is still with us, but the story of America was a wonderful story. There were portraits of Washington and Lincoln in the classrooms. We celebrated those birthdays on the actual days when people were born. We knew something of their stories—maybe not the stories that adults would hear, but these were large figures and we revered them. When the holidays went the way of “George Washington’s Birthday Mattress Day Sale,” and we focused on three-day weekends rather than celebrating the national story, things got lost.

It’s different today. A conversation with my twenty-three-year-old granddaughter features 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, the Great Recession, a failed war in Iraq, the election of Donald Trump, George Floyd, et cetera. Oh, and COVID. This is her growing up period; it’s very different from my first twenty-three years.

AS: Alexis de Tocqueville observed a variety of distinctive qualities about America in the early years of the nation’s existence. Let’s look at the distinctiveness as told in the birthing stages of this other people in the book of Exodus: the nation of Israel. What was different about the people formed in Exodus at that time? How were they distinct from every other civilization on earth to date?

LK: There are three great national or civilizational alternatives at the time of the exodus. There are the Mesopotamians, who first begin to measure the stars, who build the Tower of Babel, where all humankind comes together to build a technological refuge for humanity where man might be a god to man.

It’s going to take a lot more time to get Egypt out of the slaves than it took to get the slaves out of Egypt.

The second is Egypt. It boasts the fertility of the Nile, technology, architecture, administration; people who have sophisticated magical powers to manipulate certain kinds of phenomena. It has nature worship, but the human being has no special dignity in the cosmos. One man, Pharaoh, believed to be a god, rules despotically over all the others, primarily in his own interest.

The third alternative is waiting for them back in Canaan when they finally return. If the Egyptians are rationalist technocrats; the Canaanites are Dionysiac, earth-worshipping, fertility obsessed, and licentious. They are an orgiastic people in their celebrations.

The Israelites are neither the rational technocrats nor the Dionysiac wild people, but neither are they the mean between the two. They are something else entirely. For Israel, the human being is the Godlike creature among the creatures. It’s the only creature that is made in God’s image, with all the peril and promise that entails. It is because we are the free creature that we can live worse than the animals, but it is also because we’re the free creature in God’s image that we can rise to live a life of righteousness and holiness.

What you have in Exodus is the attempt to take a multitude living in slavery in Egypt and turn them into a people that will carry God’s way—begun in Genesis with Abraham—as a witness to the rest of the world. And that pilgrimage begins by making them see what Egypt is so they can become, first of all, an anti-Egypt.

The contest with Egypt, manifest in the plagues and the deliverance, and God’s announcement, “I am the Lord your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage,” says, “Look, Israel, you basically face two alternatives. Either you’re going to live in relation to me, or you’re going to live at the behest of some man who acquires power and who does not respect your dignity as a human being. You’re going to wind up in a house of bondage—not just of labour—but bondage over your soul and your heart and what you believe.”

Exodus presents an either/or. You start in Egypt, you learn what Egypt means, and you learn what you owe for your deliverance. At the same time, it’s going to take a lot more time to get Egypt out of the slaves than it took to get the slaves out of Egypt. And for that, they have to get a comprehensive teaching of the way of life. And it’s in this comprehensive teaching where one sees the decisive differences between Israel and the surrounding nations.

Three critical things come up in the teaching. Two of them are in the Ten Commandments. The first one is: “Remember the Sabbath day, and keep it holy.” And the second one is: “Honour your father and mother so that your days may be long upon the earth that the Lord your God has given you.” These are the only two positive commandments among the Ten Commandments, and they are absolutely new under the sun. The Sabbath teaching is for everybody—it’s not just for the master, and not just for the lady of the house. No, everybody sets aside their work for a day of rest, and the reason given is because God himself rested from his work on the seventh day.

It’s an invitation to the lowest among the low and the highest among the high to imitate God in his creation—that you have that kind of dignity to partake in a divine activity that is somehow time out of time—for gratitude, for appreciation, for worship. Not to continue to accumulate, not to toil, not to slave away your days.

And that’s in a way the beginning of a humanistic politics. The surrounding codes have separate laws for the nobles and laws for the slaves.

If you read the Code of Hammurabi, there are different punishments for killing a nobleman and for killing a commoner. In Israel, the law is given to everybody in the second-person singular, all at once. There are no distinctions.

And I think these two commandments account, in part, for the durability of the Jewish people over the centuries—two thousand years with no land of their own, often living under conditions of hostility, to say nothing of persecution. The teaching to “honour your father and mother” is the introduction of a certain reverential distance in the household, which otherwise, in other cultures, can be a den of iniquity, a nest of incest and patricide and things of that sort.

The teaching to “honour your father and mother” is the introduction of a certain reverential distance in the household.

You’ve set up certain kinds of restraints and a sacred distance in the household so that the household really can be a vehicle of transmission. In Egypt, they’re trying to find a cure for mortality. In Israel, they bury the ancestors, but teach the story of their deliverance and transmit a way of life. So the family, the sacredness to the family structure, is indispensable for a way of life that rests on the parents teaching the children to go forth in the light of what you learned, and to improve on it.

These are things that are still of interest to us. If we set aside some time from getting and spending—set aside a day of gratitude, or a day of worship, or a day of appreciation, or a day of just recognizing the astonishment of what it is to have a world and to be alive in it, not because we merit our presence here—and then to look on the parents with gratitude for their share in our coming into existence, and seeing them as the first beneficent creatures that we meet, through which we learn something of God’s beneficence, and we get from them their instruction to make a life for ourselves on a moral plane—it’s astounding.

AS: Rituals and practices are introduced that make you aware of the givenness of it all.

LK: Yes.

We started with deliverance from Egypt, and even before they go out of Egypt, they’re commanded, “Every year at this time, you will celebrate Passover, you will sacrifice the paschal lamb, you will eat flatbread, and you will tell your children of this story on that day.”

The third part of Exodus is all about the building of the tabernacle and is one of the most beautiful things. It deals with the human impulse to be in touch with what’s highest. And if they’re not told what or who is highest, they’ll sacrifice to whatever they can find. Chesterton has this line that people who don’t believe in God don’t believe in nothing; “they become capable of believing in anything.” You see that principle at work in the golden calf when Moses is gone: the people are afraid they will no longer have any access to the divine.

The tabernacle is a place where people are given the opportunity to express their longings for some relationship with God. To make offerings of gratitude or of atonement. To come together communally. To sacrifice in worship, and eventually in song. To feel something of the experience of the divine presence in their midst. The tabernacle is a place built under the architectural instruction given by God himself, who was even a furniture designer. They have to erect this building in partnership with him, like Noah’s ark.

Just as God gave instructions for the ark, and Noah built it, he gives instructions for the tabernacle, and the people erect it. Inside the tabernacle is the ark containing his law. They gather together in a building that he designed and they erected. God says, “I took up with Israel. Why? So that they might know me and that I might abide among them”—a beautiful sentence. The whole story of the creation depends on God’s being known by his creature, the one who is most alike to him, and they encounter him—his presence—in their everyday life.

Here is an answer to people’s longings for something more than comfort and safety, something more than being recompensed for torts or putting the bad guys in prison.

We all have some deeper aspirations for something eternal, for something true and good. It was the genius of this founding to address it. There are many ways in which that kind of religious impulse can go wrong—it can go wrong in tyranny or theocracies; it can go wrong in cancel culture; it can go wrong in licentious, wild, orgiastic practices. Yet this is a way that, despite all the odds, survives. Thanks also to Christianity, some of its teachings spread through the West, and they are one of the indispensable threads of the civilization that we are blessed to be part of.

AS: I get goosebumps when I hear this. Thank you.

In my journalistic work, when I’ve outlined the principles of flourishing community life that endure across time, some people in our secular age say, “Well, those principles sound religious.” There’s an anthropological genius in religion—I would say all religions—that seems to be singularly smart about human flourishing, human relationship, human longing. Does formation of a people and divine revelation need to be connected?

LK: I don’t want to say that there has to be something like Sinai or the coming of Christ in the New Testament to be the telos and the anchor point of a community. I don’t think I know enough to say that that’s necessary. But there has to be some intimation, it seems to me, of something eternal, something greater than ourselves.

Here is an answer to people’s longings for something more than comfort and safety, something more than being recompensed for torts or putting the bad guys in prison.

It doesn’t sound like religion of the sort that we know, but the insight of what the world somehow requires for its existence, its directed strivings and movements, its intelligibility. There have been people outside the Judeo-Christian tradition who’ve had glimpses of this—Plato for instance. Whether those philosophical teachings sustain a civilization . . . that’s a different question. There are no Platonic cities, but there is Western civilization.

So I don’t want to answer your question simply in the affirmative, even for the world at large. But I do think that something opened up into the world that changed the course of its history. You can call it prophecy, you can call it revelation. Somebody was in touch with something absolutely out of this world, and it’s made all the difference in this world for the people who heard it, talked about it, and passed it on to the young. It’s made all the difference for those who communed with it, as communities, in their places of ritual and worship. That in itself is astonishing. It’s just astonishing.

AS: Exodus does seem to suggest—and certainly the rest of the Torah and subsequent prophets that follow do too—that people-building is very hard, disappointing work over generations. It’s not guaranteed to succeed.

Throughout history and certainly today, we’ve asked questions about the rise and fall of nations. But the people of Israel is unique in their enduring power. Could you describe some of the repeated pitfalls that are part of this story, where there’s a lot of disappointing God? And then, to borrow a Christian word, the patterned graces in the story?

LK: This is good, because if you stopped at the end of Exodus, you might be very hopeful. And the story, at least in the Hebrew Bible itself, is really more a story of failure than of success. The very end of Chronicles is bad news; pretty grim. But God gave Israel a huge project: to be a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. For a bunch of ex-slaves to be given this kind of call was, on the one hand, really exciting, and they could probably take a big part on the historical stage. But who were they to undertake this?

They’re subject to all the foibles of human nature that Genesis makes perfectly evident to us: Fear, greed, envy, pride, stiff-neckedness. God gives the commandments, but then he gives rules about how to deal with when (not if) people break those commandments. In fact, they start murmuring against Moses right after the deliverance.

Then you’ve got the elite who are filled with envy, and you have the rebellion of Korah. There is murder, jockeying for power, adultery. The demands of this observance are very, very great.

I think the episode with the golden calf is deliberate. Sooner or later, the people would fall away, so let’s find out early what happens when they fall away completely into apostasy. As a result of that, Moses has to plead for their existence with God, and he gets a brief revelation—not of God’s nature, but some of his qualities from the backside. What he learns for the first time—and it’s absolutely indispensable—is that God is filled with forgiveness and grace. He’s not just a just and fiery God or a man of war. He’s capable of forgiveness, and that means that the people are willing to aim high even though they know they’re going to fail, because there is the possibility to repent regularly, to seek forgiveness, to start over.

That’s a remarkable God. And in the absence of some kind of assurance of that grace, no one would even aim high. There’s something built in here to deal with the problem of human failure.

Let me say one further thing.

Maybe to be a kingdom of priests and a holy nation isn’t a recipe for surviving politically on the earth. Maybe you’re there to be a moral witness. And I don’t know to what extent the failure is that they were given a call to be different from all the other nations in the world, but were somehow not able to survive very well among them.

AS: Forgive me for jumping forward thousands of years again, but let’s return to this notion of failings. I take it well when you say these failings were, in some sense, just human failings. But is there wisdom to be gleaned from Exodus around dealing with sin and transgression within your own people?

I think about this in our particular current American context. However secular we’ve become, we’ve simultaneously embraced a language that acknowledges systemic moral issues. A lot of people are asking, “Okay, we’re increasingly taking to heart this history we’ve inherited that is far from perfect, and yet many of us want to be in the business of perfecting and not destroying.” Is there wisdom to be gleaned from the book of Exodus in navigating these waters? I ask in no small part because the United States has often treated the Exodus narrative as a motif of its own identity—the immigrant journey, the slavery to freedom journey. But if that narrative is no longer resonating with younger generations, maybe we need to start thinking more in terms of redemption, not simply exodus. Is there practical wisdom embedded in this book for how we take responsibility for transgressions that may have come before us, but nonetheless implicate us?

LK: I think you’re right that if you treat it non-cynically, and you try to put the best construction on some of today’s calls for an accounting of our historical sins, there seems to be a quasi-religious demand for repentance, expiation, and rededication. It’s the language of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg, and in his Second Inaugural Address. It’s the language of Martin Luther King Jr., who summoned the country to be true to its original and most edifying principles. In King’s case, he could repair to the Declaration of Independence and to the founding sentiments of the preamble of the Constitution and to the brotherhood of man under the fatherhood of God. Because the civil rights movement of the ’60s was a movement led by the churches and sung in the churches, marched for religiously. The whole notion of civil disobedience required purification, and accepting the consequence of breaking the law was aimed at pricking the conscience of the nation to return to the better angels of its being.

That was also the way that the biblical prophets of Israel always summoned Israel to return to the original call, to the original covenant. To be true to what we promised, to be true to what’s been expected of us—in Hebrew, to do teshuva, which is to return, turn around. It’s very hard to try to teach the lesson of turning around when the angry people want to condemn the only principles in the name of which you could ask people to turn around. If the roots are simply poisonous, then the only remedy is to uproot them, and that’s really a call for overthrow and destruction.

You want to talk about housing, you want to talk about schools, you want to talk about family structure, you want to talk about work? Let’s talk about those things. Where are we to go for rectification if not “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal”? Where are we going to go if not to remember, you too were strangers in a strange land, so treat the outsider who lives among you or the widows or the orphans or the poor with a dignity that any creature made in God’s image is entitled to?

In America, the moral founding is not merely in politics. It’s also in the biblical religion that is the moral founding of the societies, the families, and the people in their locality. So you have liberal political institutions and a certain Christian moral social order. Both of them are things to which we could appeal today if one wanted to try to heal the country—not in its tribal structure, but in its Unum. That’s the task; there are principles of the Unum that any decent American today could subscribe to.

AS: Turning now to your own reading of the text: Was there a particular character that really gripped you?

LK: Moses is the central attraction. Born a Levite, raised in Pharaoh’s house as a prince, we have no idea what he was taught, but he got a princely education. He comes out from the palace for the first time, and he can’t stand bullying: he responds with anger and fellow feeling three times on behalf of the underdog, and he fails in two of them.

In the third one, he gets himself a wife from Jethro in Midian, and then Moses goes to see why the burning bush isn’t consumed. The patriarchs never asked why, but Moses has a philosophical interest in the causes of things—that’s his Egyptian education. Moses goes with a philosophical question, and God turns the philosophical question on its ear. He asks for God’s name, he wants to know God’s essence, and God gives him a mysterious non-answer: “I will be what I will be. Pay attention, Moses, you’ll know about me from what I say and do. That should be enough for you.” For the time being, it’s enough. Moses will ask him later on, “Let me see your glory, I really want to know you much better.”

There are no Platonic cities, but there is Western civilization.

He gets to know God in a conversation face-to-face, as one speaks with a friend. And in the last encounter, he comes down with God’s light shining off of his face. He’s been touched by this divine encounter and radiates that light into the community. He gets this voice in his head when he’s eighty years old, and the voice talks to him, and he learns from this voice. He learns somehow to anticipate where the voice is going and takes some initiative on his own. Sometimes it backfires, but you see a man become a prophet right under your nose.

And what a charge he has. Six hundred thousand slavish men, grumbling, murmuring. He doesn’t know what to do with them. He sees that they get a law, he gets them through dire straits, they win a victory against the Amalekites . . . it’s a stunning story.

AS: How did the book at large start to take a hold of you?

LK: The book did something to me in the last two years of working on it.

I never paid the tabernacle any attention at all. I thought the tabernacle was a place that you had to build in order to restrain or confine the wild passions of the people who have to get drunk on Saturday night or have some orgy when they want to be together.

I was never one for rock concerts. I’m more Apollonian than Dionysiac. I thought this was just a concession to human weakness. But if you’re saying, “Let’s be faithful to the text,” then who’s to decide but the text what the important passages are? They’re all in here for a reason. Figure it out.

I got to work on this. The instructions for building the tabernacle are seven chapters long, and Moses doesn’t say a word. God is speaking as if he cares about footstools and designs every detail. Seven chapters of boring detail, and then again almost verbatim in six more chapters at the end, describing the building of the tabernacle according to the instructions. The golden calf is sandwiched in between them as if to say the tabernacle exists to sandwich the passions that erupt in the episode with the golden calf. And that was what I thought it was. It was as if you had a split screen: watch what the people are doing downstairs, while Moses is getting the instructions up here for correcting what the people are doing there. You want to have sacrifices, you want to have dancing, you want to have this stuff? Here’s how we’re going to do it.

But then I stumbled on this passage where God says that he’s taken up with Israel so that he might abide among them, that he shall be known by them. And then you see that the tabernacle is filled with all kinds of allusions to the story of Genesis 1 and the creation—six days of this and that, and he saw that it was good, and he blessed them. All kinds of things that are echoes of the beginning. The last ten pages of my book treat the tabernacle as the completion of the creation, where God’s creature, made in his image, finally gets to know of his existence—not just once at Sinai, but every day. To experience his presence in the ordering of his everyday life in the place where people come to be in touch with him. Exodus seems to be a story about Moses and the tabernacle, but it’s really about God—the same mysterious God we read about in Genesis.

This coincides with certain experiences in my own latter-day synagogue experience, and it makes me think I may have some idea what they’re talking about here. When the community gathers together and lifts its voice in song and in prayer, something happens to you. You’re encountering something. I can’t put a name to it. But you’re experiencing something that lifts your soul up to a new place, and you encounter something that you didn’t have when you walked in there. So it’s a very pleasant surprise in my old age.

AS: The core thing that always hits me, in both reading you and watching you in the early days of my own career, is how much the reading of a text for its own sake is always a sacred task to you. This particular book you’ve written is detailed, yes—you go through every verse—but it reads very much like a narrative. There’s a tenderness to it; a reader picks up that a deeply intellectual human being been profoundly changed by a text, and that you are inviting people into that same experience. I find this so rare—so many of us tend to over-apply a text, I commit this sin often myself in trying to respond earnestly to the crises of my own time. But something in your book bade me slow down. You allowed a window into the hunger in your soul that tapped my own.

LK: I’m touched by how many people are actually interested in Exodus. People are interested in Genesis, but that doesn’t get you very far into religion; God doesn’t ask anything much of anybody. So you can read it for these nice stories, and you can feel superior to all those people because this one killed his brother, this one cheated her husband, et cetera, et cetera. But I find that for some reason, Exodus is really on people’s minds.

AS: I agree. I think there’s something specifically going on in the United States vis-à-vis Exodus, a reckoning with this narrative that we relate to as a nation. There has been a revival of interest in the basic building blocks of a society that so many worry is crumbling. There’s this hunger, more than I can remember even five years ago, to understand how we got here, and where we can pick up the pieces from here. And Exodus hints at answers.

LK: Actually, what you’ve just said taught me something that I’d never seen before. And it’s what I should have said right away in answer to the question about divine revelation. I was thinking about whether there has to be a divinely given teaching. But it really is that moment at Sinai.

The children of Israel are so frightened that they stand far off, and I doubt they heard a word of the Ten Commandments, because they say to Moses, “You speak to us lest we die.” So the text says, “The people saw the thunder.” And the translators can’t translate that because you can’t “see” thunder. So they say “perceived.” But they have this synesthesia, where the senses are mixed up together. At that moment, every single Israelite has the same exact encounter with God. That is the moment that they are all together, addressed all together, but in the second-person singular. That’s where they’ve been offered an opportunity for a permanent covenant with God.

AS: That fundamental relationship with fidelity.

LK: Yes. Everything else we can argue about, you could say. But as long as we have that, we share a common directionality.

Irving Kristol had a nice formulation. He described himself as theotropic. Have you heard that before?

AS: I haven’t.

LK: Plants are called heliotropic because they are directed toward the sun or the light. Irving described himself as directed toward God. He didn’t say what he meant by it, but that’s another way of describing the latent longings of human beings. If they have this moment where that latent longing is actually satisfied by an encounter, that’s permanently transforming—so long as they tell the story.

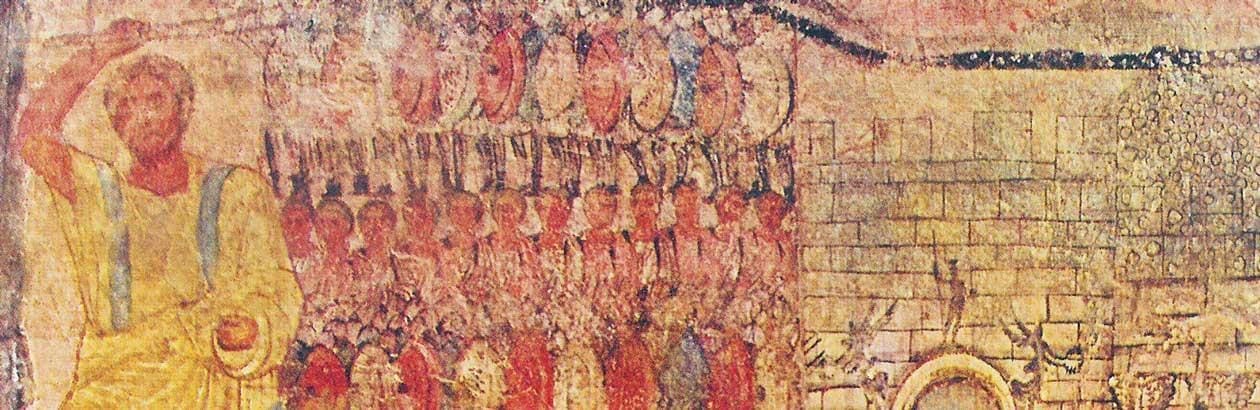

Image: Wall painting depicting Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt, from the synagogue in Dura-Europos, Syria, circa 245 AD.