M

And if he refuses to listen . . . let him be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector.

—Matthew 18:17

My father was my first teacher in forgiveness. His frequent absence, sporadic contributions to assist my mom with my care, and unfair ability to cause me to forget all his failings with a smile made loving and liking him hard. I lit up any time he entered a room, and I painfully longed for his presence and affection when he didn’t. I was a daddy’s girl without a dad, who spent countless days standing by the screen door, eagerly waiting for him to fulfill his promise that he would come. Though I had the constant love and affection of a fierce grandmother and a mother who drew strength from the Lord daily to ensure I had everything I ever needed or wanted, I spent most of my childhood trying to answer this nagging question: Why isn’t my dad here?

The answers were in the tingly smell that often came with hugs and the slur of his tongue on the rare occasion he called. But as a kid, you don’t know the signs of alcoholism; you don’t even have a word for it. All you know is the pain that your dad isn’t there.

This pain would be one of the first I took to Jesus. I was nineteen, excited about my new-found relationship with him, and ready to pick up my cross and follow him wherever he led. My zeal quickly faded, however, and my grip on the cross weakened when I encountered Jesus’s teachings on forgiveness. Every time I read these passages in my Bible, thoughts of my dad would flood my mind, and I would try to turn them off like a faucet. I told myself why he was undeserving, how his alcoholism made him unsafe relationally, and how I didn’t really know how to get in touch with him anyway. Even if I was interested in adjusting my grip on the cross and following Jesus down the path that leads to forgiveness, what was forgiveness supposed to look and feel like? Did it mean sending birthday and Father’s Day cards? Did it mean not being mad at him anymore and making another go at being a daddy’s girl? What was Jesus expecting and requiring of me?

What does forgiveness mean, I wondered, and how could I be assured I’d done it? What is the defining measure of reconciliation? Is there ever any recourse for extending forgiveness but withholding reconciliation?

For years, with my Bible open and in thoughtful conversations with others, I wrestled deeply with these questions. I felt stuck. Even when my heart was ready to forgive, I wasn’t sure where to start. I didn’t fully know what it meant. I wanted to be reconciled to my dad, but I didn’t know whether that was wise. What does forgiveness mean, I wondered, and how could I be assured I’d done it? What is the defining measure of reconciliation? Is there ever any recourse for extending forgiveness but withholding reconciliation?

Many of us wrestle with these questions. But the Bible does provide answers, laying out for us the terms and conditions under which forgiveness should and should not be followed by reconciliation. Forgiveness and reconciliation are often conflated and thus misunderstood. So before we get to the terms and conditions, let’s look at the terms and definitions.

Terms + Definitions

Here is my definition of forgiveness: Forgiveness is the committed decision of the offended to not retaliate against an offender and instead release them from receiving the just punishment their offence deserves. It’s the choice to acknowledge your offender’s wrong but, in mercy, not to harm them in return or to require restitution for the rupture their offence has caused to your overall sense of safety, security, and shalom. Reconciliation, on the other hand, has a different definition: Reconciliation is the committed decision of both the offended and the offender to do the hard work of restoring safety, security, and shalom to the relationship. It’s the two of them rolling up their sleeves, getting into the dirt of their relationship to uproot the weeds of distrust, shame, and distance, and sowing seeds of changed behaviour, vulnerability, and practices of trust.

Understanding this distinction between forgiveness and reconciliation is pivotal for anyone seeking to engage in the work of either of them. And let me be clear: it is work. It is not a feeling, and the work is not complete after you have uttered, privately or publicly, the words “I forgive.” This distinction also clarifies that forgiveness is the solo work of the offended, and reconciliation is the shared work of both the offended and their offender. You have the agency and ability to forgive someone apart from their confession or apology. You are free to release them from paying back what they owe you because of their sin against you. This is good news! You don’t have to wait for their apology or restitution to have your sense of safety, security, and shalom restored. Depending on the offence, even your offender’s best efforts couldn’t restore what was lost. Only God himself can “restore, establish, strengthen, and support” you and cause you to make a full recovery from the pain and fallout of the offence (1 Peter 5:10). You can abandon your inclination to retaliate and resolve your anger in the truth that “‘vengeance belongs to me; I will repay,’ says the Lord” (Romans 12:19). You can set the offender free and leave them in hands that are more just than yours. Your ability to obey Jesus’s command to forgive so that you will be forgiven is not contingent or dependent on them (Matthew 6:14; Mark 11:25; Luke 6:37). Forgiveness is a work solely contingent and dependent on you and your obedience to Christ. Reconciliation is not.

As Christians who have been forgiven and reconciled to God through the shed blood of Jesus Christ, it is fitting for us to long for forgiveness to bear the fruit of reconciliation. We are people not only whose fate is contingent on this work but also whose faith centres on a God who pours his whole self into the work of reconciliation in the person of Jesus Christ. From the moment Adam and Eve rebelled against him and were consequently removed from his presence, God has been on a singular mission—to reconcile all things to himself. In his letter to the church at Ephesus, the apostle Paul pulls back the curtain and centres our attention on this mission: “[God] made known to us the mystery of his will, according to his good pleasure that he purposed in Christ as a plan for the right time—to bring everything together in Christ, both things in the heaven and things on earth in him” (Ephesians 1:9–10).

It’s as if Paul were saying, “Do you want to know what God has been up to since the beginning of time? Do you understand why he sent his Son Jesus into the world? Do you know what’s at the centre of his heart and all his activity in the world? It’s this: to repair every tear, crack, and break in his good creation. It’s to restore wholeness to his broken and fallen world by reconciling all things everywhere back to himself and to one another.”

If this God is our Father by way of the reconciling blood of Jesus Christ, then reconciliation is embedded in our spiritual DNA.

If reconciliation is at the centre of our God’s heart, then it should also shape the hearts of his people. If this God is our Father by way of the reconciling blood of Jesus Christ, then reconciliation is embedded in our spiritual DNA. I wonder whether this reality is what has created so much curiosity and angst around the question of whether it is possible to forgive someone but not reconcile with them. Like our God, we long for our stories to end with reconciliation. We long for what has been broken by sin to be restored to shalom. Isn’t this the crux of our faith? However, we also wrestle with curiosity and angst around this question because we don’t want to get hurt . . . again. We just can’t take the risk of incurring more pain or dissonance. Plus, what if the person is unwilling to reconcile? What if they are unwilling to get into the dirt with me? Then what? Do I give up or keep calling? Or, even more importantly, what if the person is physically, emotionally, and spiritually unsafe? Does Jesus really want me to turn the other cheek, stay in the relationship, and give the person an opportunity to slap me over and over again? Under what conditions should forgiveness be followed by reconciliation?

Terms + Conditions

If you’ve ever felt guilty about posing these questions to God in prayer or in conversation with others, let me assure you of these two truths: you are not alone, and Jesus doesn’t condemn you for asking these questions. In fact, he anticipates them and provides us with answers that are clear, practical, and compelling. In both his life and his teaching, he lays out for his disciples the terms and conditions for when to move beyond an offence toward the hard yet worthy work of reconciliation.

As for his life, Jesus spells out for his disciples the terms and conditions for forgiveness and reconciliation through his atoning work on the cross. Jesus does the solo work of providing forgiveness for the entire past-present-future human race. His death was a forgiving act of his own choosing, and it was done apart from the apology, retribution, or repentance of his offenders. While we were yet sinners, Christ died, and even as his body transitioned from life to death, he called on God to forgive our senseless actions (Luke 23:24; Romans 5:6). He forgave us willingly, freely, and fully. When it comes to his work of forgiveness, there are no terms and conditions that predicate its existence.

However, there are terms and conditions for the joy of its experience—faith and repentance. We must claim Jesus’s atoning work on the cross as the only means by which our relationship with God can be restored. We must respond to Jesus’s call to “repent and believe in the gospel” (Mark 1:15). Those are the terms and conditions for experiencing the gift of God’s forgiveness and being reconciled to him. It’s to those who receive him and believe in his name that Christ gives the right to become the reconciled children of God (John 1:12).

Through his life, Jesus leaves us this guiding principle: extend forgiveness to everybody, but reserve reconciliation for the repentant. With his life he says to us, “Beloved, even if they never apologize, join me in willingly, freely, and fully forgiving them. They may stiff-arm your forgiveness, but don’t stiffen your arm against my call to extend mercy and grace. Even if they sin against you seventy-seven times, with eyes fixed on me and my death for your list of sins that no one could count but me, forgive.”

Jesus never asks us to do something he has not already done. He is not a “do as I say, not as I do” kind of rabbi. He is a “come and follow me” kind of rabbi. He set the tone, providing us with inspiration and the blueprint for graciously forgiving others. But that’s not all he does; he also provides us with inspiration and a blueprint for reconciliation. Only those who confess, repent, and believe in him are reconciled to a relationship with him. Without confession, repentance, and faith in him, reconciliation is impossible, and the relational distance remains. If these are Jesus’s terms and conditions for restoring relationships with those who have sinned against him, how much more should they be ours?

As for his teaching, in Matthew 18:15–20 Jesus shares these words with his disciples:

If your brother sins against you, go tell him his fault, between you and him alone. If he listens to you, you have won your brother. But if he won’t listen, take one or two others with you, so that by the testimony of two or three witnesses every fact may be established. If he doesn’t pay attention to them, tell the church. If he doesn’t pay attention even to the church, let him be like a Gentile and a tax collector to you. Truly I tell you, whatever you bind on earth will have been bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will have been loosed in heaven. Again, truly I tell you, if two of you on earth agree about any matter that you pray for, it will be done for you by my Father in heaven. For where two or three are gathered together in my name, I am there among them.

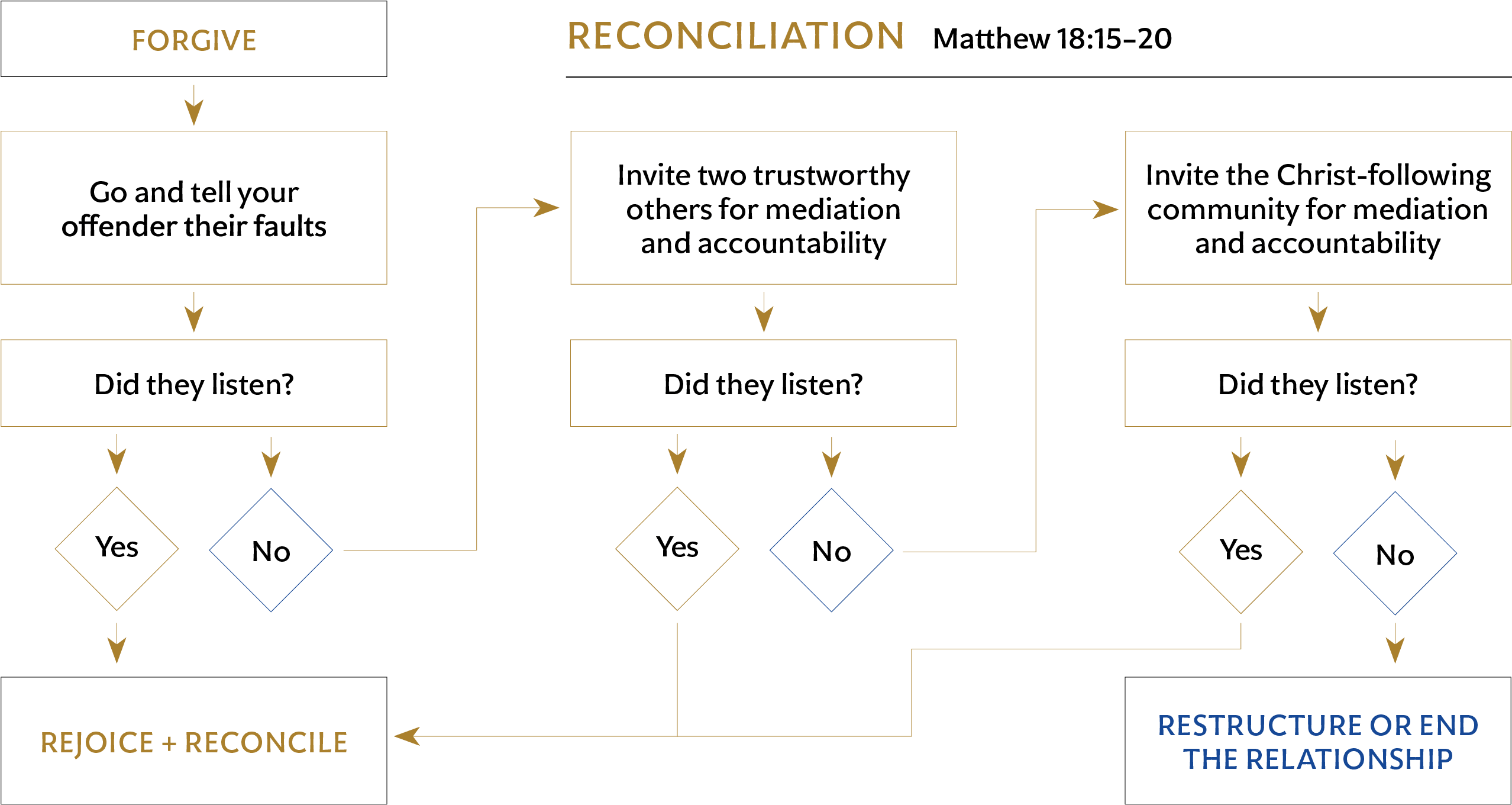

To guard us from making hasty decisions to restructure or end relationships with those who’ve hurt or harmed us, Jesus puts some terms and conditions in place for us to follow. He commands us to first go to our offender privately. Then, if the conversation reaches a dead end, he counsels us to invite two trustworthy people into the dialogue for mediation and accountability. If both of these efforts fail, Jesus then instructs us to invite the church—the Christ-following community—to compel the offender to confess and repent. His instructions in Matthew 18:15–20 read like a kind of flow chart.

The terms and conditions for reconciliation are listening. If the person denies, blame-shifts, gaslights, or reinterprets the truth, Jesus calls for a relational shift. If their listening doesn’t yield the fruit of confession and repentance, Jesus says to regard them as a brother or sister no longer and instead treat them as a Gentile and tax collector. “Confession” and “repentance” are also words that often get conflated. Confession in Scripture is an admittance of wrong that agrees with God’s definition of right and wrong—not our own. When we confront a person about their sin against us, we must be sure our offence finds its credibility in God. And if the two of us, along with the two trustworthy witnesses we’ve brought in to mediate and the Christ-following community brought in for accountability, can’t agree on whether the offence is founded, reconciliation isn’t possible.

In the Scriptures, listening is more than merely hearing what another person has said; it is agreeing and believing that what has been said against an offender is true and responding or repenting accordingly. Repentance is turning away from a way of thinking or behaving in opposition to God and his ways and, instead, bringing our way of thinking and behaving in alignment with him. Once again, the emphasis is on God and his ways, not our own. When our calls for repentance don’t find their credibility in what God desires, we are likely demanding or requiring more from others than what God requires. We are asking them to live up to our standards, not God’s. But when our calls for repentance are anchored in God and his ways, we have the blessed assurance of knowing that what we are asking is fair. However, if the offender does not agree with or believe God and his ways, Jesus calls us to restructure the relationship by establishing stricter boundaries and altering our relational rhythms, or ending the relationship altogether.

When our calls for repentance don’t find their credibility in what God desires, we are likely demanding or requiring more from others than what God requires.

Though Jesus’s teaching on reconciliation is straightforward, depending on the nature of the relationship, we are often tempted not to follow it. We can hang on to the relationship for too long because the pain of bringing it to an end seems more unbearable than the pain of staying in it, or we can let go of it too soon because we anxiously feel the need to protect our peace. When it’s the latter, our modus operandi is to skip Jesus’s instruction to confront the offender privately and instead vent and gossip to a friend. And even if we do confront the offender privately, we end our pursuit of reconciliation there. If they are unwilling to cooperate, we inform those closest to us that the relationship is over and stop inviting the offender to the cookout or the group chat or the family gathering. I know all this because the “we” in these sentences is me. However, as I’ve pored over this text and applied its wisdom, I have come to understand the brilliance of Jesus’s instruction.

When we are hurt and in the thick of conflict with someone we love, we are not always good judges. We need to bring in others to ensure that we are seeing things clearly. We need the two witnesses to help us discern whether our complaint is justified. We need the Christ-following community to help us discern whether reconciliation is possible and, if not, how to move forward. These principles can still apply even when our grievances are with a person who doesn’t know Jesus and is not a part of our Christ-following community. The conversation will no doubt look different, but as followers of Jesus we are still called to confront those who offend us. Bringing in a trustworthy friend from church to mediate a conflict may be unwise, but we can bring in a counsellor, a wise auntie, or a trusted co-worker. Likewise, we may not always be able to bring in our pastor or Christ-following community to help, but we can always seek them out for counsel.

So, is there recourse when forgiving is possible but reconciliation is not? Yes, but it is difficult. Yet the last three verses in the Matthew passage fill me with a deep sense of gratitude. Knowing how painful it would be to restructure or end a relationship with someone we love, Jesus adds these reassuring words:

Truly I tell you, whatever you bind on earth will have been bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will have been loosed in heaven. Again, truly I tell you, if two of you on earth agree about any matter that you pray for, it will be done for you by my Father in heaven. For where two or three are gathered together in my name, I am there among them. (Matthew 18:18–20)

Jesus knows ending a relationship with someone we love and once trusted hurts. He knows that we will be reluctant to part ways with a spouse we vowed never to leave or forsake apart from death, or with a family member whose love we’ve always longed for, or with a friend we never categorized as seasonal. He’s aware that we will question our decision to leave, even if it is in agreement with the principles he lays out. He’s acquainted with the pain of irreconcilable difference. He knows that we have a tendency to misread, misinterpret, and misapply his commands to love our enemy and turn the other cheek. In his closing statements to his teaching on reconciliation, he says in essence, “If your offender will not listen and the judgment of the Christ-following community is to end the relationship, I’m with you. Whatever the Christ-following community decides, I will have your back.”

Jesus’s closing statement has brought me so much comfort through the years. Whenever I have questioned whether I made the right decision to restructure or end a relationship, I return to these words for clarity and direction. Sometimes the clarity affirms my decision and directs me to keep the relationship the way it is while still praying for reconciliation. Other times it does not and directs me to go back to my offender to seek reconciliation. Upon more reflection the Spirit may reveal that I didn’t fully pursue reconciliation, or new evidence about my offender, their offence, or even myself might beckon me to try again.

All throughout my twenties, the Spirit did this kind of work, revealing to me the depth of my father’s alcoholism, reminding me of how present he was during his seasons of sobriety, and exposing how my unforgiveness and bitterness were making the relationship worse. So I readjusted my grip on the cross, chose to forgive, and began pursuing reconciliation with my father. I was initially met with painful dead ends. I couldn’t tell whether he was genuinely uninterested or just too bound by shame. Either way, after years of trying and years of collecting the pain of new hurts, I was advised by those in my Christ-following community to restructure the relationship and resolve to pray for God to change my dad’s heart.

Though I often questioned whether I made the right decision to step back from the relationship with my dad, I found solace in Christ’s teaching. Reconciliation takes two, and I couldn’t will it on my own. So I prayed and waited at the screen door of my heart for my dad to make repentant steps toward me.

Just as I was settling into my thirties, my dad called asking for forgiveness. He was sober and wanted to build a relationship. We were able to write an alternate ending to our story. We only got two years together before he passed, but I’m thankful. I got my dad back. I still endure the pain of broken friendships and familial relationships; our world is filled with such sorrows. Even so, I wait with hope that these stories will find their alternate endings. Because through my dad God taught me not only how to do the hard work of forgiveness but also about the joy of getting into the dirt for the sake of reconciliation.