F

Forgiveness may be one of the most difficult words to pronounce in the Christian vocabulary. We find it hard to utter not because it is spelled in a way that is difficult to enunciate but because its experience so often eludes us. How dare we invoke a concept that can feel like a slap in the face of sustained injustice?

Yet forgiveness is a foundational concept of the gospel of salvation and a basic conviction of Christian discipleship. So how do we handle something this potent and not misuse it? Is there evidence that human beings can be trusted with the sacred?

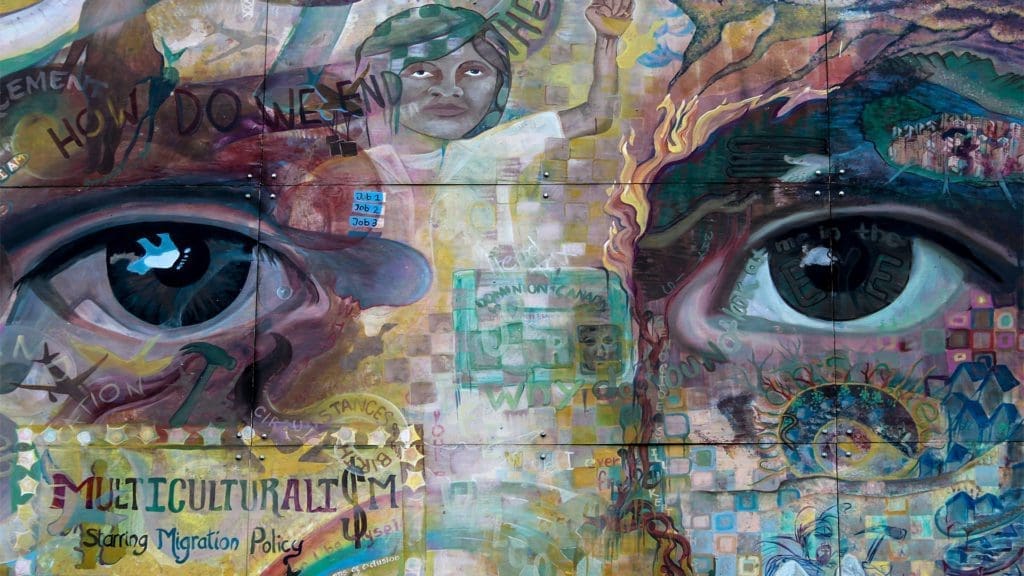

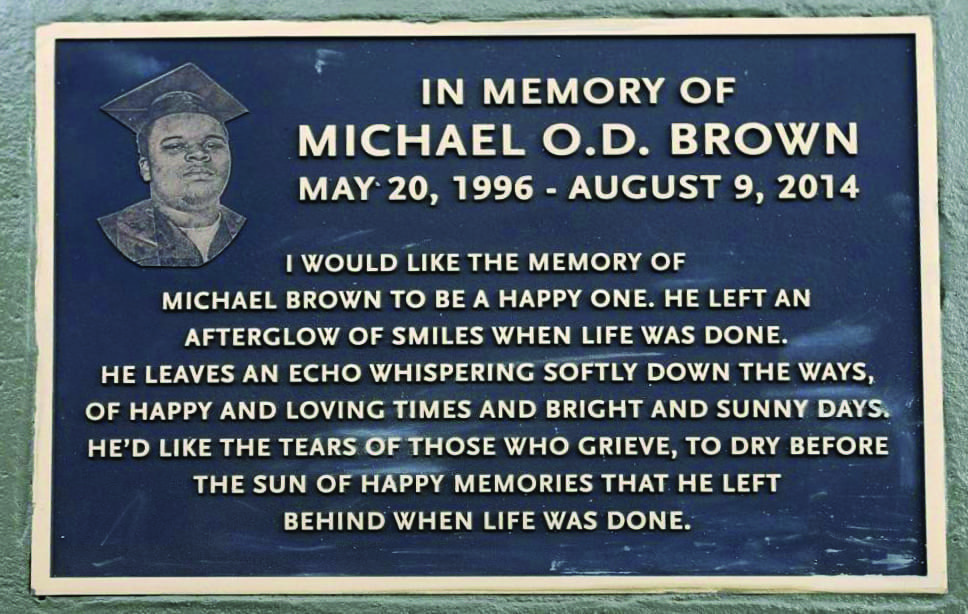

This summer I moved from Chicago to St. Louis, a city that has been grieving the tenth anniversary of the death of unarmed eighteen-year-old Michael Brown Jr. at the hands of a white police officer in neighbouring Ferguson. There have been many occasions of remembrance, and I have participated as a way of listening to the mourning song of this city I am learning to call home. I’ve stood in solidarity with Brown’s still-grieving family, and I’ve walked the neighbourhood where he was killed. I’ve listened to the various groups that were born in the aftermath of Brown’s murder to demand justice, and I’ve accompanied St. Louis’s Christian community as its varied strains grieve and remember. Amid the deep emotion still pervading St. Louis one decade later, I have wondered about raising forgiveness as a topic of discussion. It feels necessary but also risky. How does one invite the regenerative power of forgiveness without re-wounding a traumatized community?

As they have with other words in the Christian lexicon—think “sin,” “sacrifice,” “submit”—Christians have tended to convert discussions of forgiveness into awkward, even harmful expressions when applied to situations like Mike Brown’s death. Targets of racism bear a societal expectation to forgive racists, and often we do, assuming that Christian kindness displayed over and over can alter a racist worldview. Not dissimilarly, abuse victims are routinely expected to forgive and forget, re-subjecting themselves to malevolent imitations of Christ. Such experiences begin to persuade a person that it’s safer to live a Christian life without reckoning with the requirements of forgiveness—both the word itself and its practice.

Yet as a Christian at home inside a tradition of black Christian protest, I would like to encourage us not to flee considerations of forgiveness in the wake of Ferguson’s trauma. Brown’s murder played a catalytic role in awakening Americans to all that remains wrong in our shared—and yet also traumatically unshared—civic life. It is a great American irony that forgiveness is that part of the Christian story most likely to go unmentioned in our secular public square at the very moment it inhabits a nearly unrivalled note of stillness—and thus power—in bearing political hope. Genuine forgiveness is foundational to sustaining a society not only in its capacity to reconcile broken relationships but in its healing of the rancour that harmful encounters deposit within our souls. Unfortunately, much of today’s discourse around forgiveness has a specious quality: the word moves a crowd emotionally only to be manipulated to prop up the same old hierarchies. Barack Obama was applauded as he sang “Amazing Grace” at the funeral of Clementa Pinckney, who was murdered by a white racist in a state that still flew the Confederate flag at its capital building. Meanwhile, Colin Kaepernick was denounced for his ingratitude as he knelt during the national anthem in tribute to US victims of white supremacy.

We have to get clear on the ways in which our language around forgiveness can be abused before we’re able to recover healthier possibilities for genuine communion.

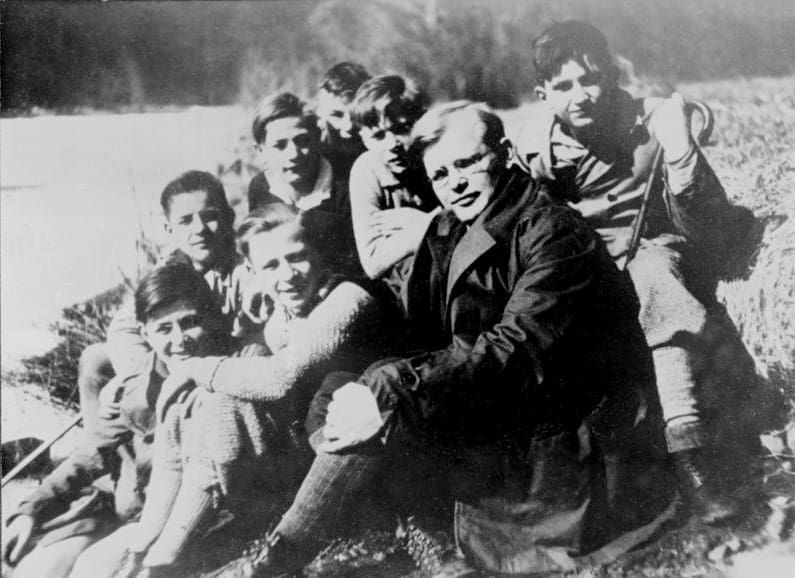

Learning from Bonhoeffer

As a word, “forgiveness” means letting go. It is the release of obligations or accrued debts. In the New Testament, forgiveness is God’s gift of mercy to a fallen world through Christ. It is the reversal of Genesis 3, when relationships were broken between God and humanity, between humans, and between humanity and the rest of creation. Forgiveness is how peace, redemption, and the recovery of right relationships are made possible.

But how does this work in the context of our collective life? Can forgiveness find a footing in broader systemic realities?

Dietrich Bonhoeffer located the birthplace of forgiveness in the personhood of Christ—that singular point offering a path of redemption for our relational lives. For Bonhoeffer, forgiveness is not merely an action that one performs as a matter of conscience; it accompanies confession in the practice of being-for-others. Being-for-others is who Christ is, what Christ does, and what Christ enables in us. Christ is the second Adam who vicariously stands in for us before God and before others as mediator, voluntarily taking our shame and suffering, and releasing us from the captivity of the heart turned in on itself, into the capacity to be free for others. To be in Christ is to participate in this life of the mediator—to turn from judgmentalism toward a willing embrace of your neighbours’ shame and suffering, which also means toward forgiveness. As Clifford Green describes, Christ does not mediate as one who presides over a dispute, but rather mediates the way our beliefs, images, and stereotypes do: Christ’s presence in and with his followers reshapes the way we perceive and relate to other people and groups. “This is quite evident in people with strong racial or antisemitic prejudices,” writes Green, but “Bonhoeffer argues that in Christian community it is Christ who is mediator of all experience and relationships.”

Bonhoeffer’s concept of forgiveness is importantly communitarian: it is not merely an aspect of a private Christian life; it is a social practice that is intended to help members of a covenantal community overcome the effects of the fall. But it gets more complicated when we consider Bonhoeffer’s understanding of forgiveness within a society that is as racialized as the United States.

In our political practice of life together, demands for justice routinely highlight how black people shoulder the sin and shame of society. One need only look as far back as this summer’s political theatre, when US vice presidential candidate J.D. Vance doubled down on claims that a black population of Haitian immigrants were abducting and eating the pets of residents of Springfield, Ohio, to see an ongoing pattern of highly targeted scapegoating. We must speak plainly: black people remain the imputed embodiment of the nation’s ills. In the words of James Cone, they become sin for the guilt-shaped society—stereotyped, typified, castigated—and are placed on crosses, which is to say, sacrificed through disproportionate use of state-sanctioned violence against them, to secure the good and holy community idealized by a racial imagination.

In 2012, two years prior to Mike Brown’s lethal encounter with law enforcement, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a report with the following findings:

Consistent with prior research, black victims were substantially over-represented [as victims in a lethal encounter] relative to the U.S. population, comprising 34% of victims but only 13% of Americans, and with legal intervention death rates 2.8 times higher than those among whites. Black victims were also more likely to be unarmed than whites or Hispanics, and less likely than whites to have evidence suggesting an immediate threat to law enforcement.

To some, these findings from the CDC indicate that blacks have more contact with law enforcement because of higher propensity toward criminality. But that is not how the report reads. The report includes the assessment that “racial inequities in legal intervention fatalities may reflect differences in the way that some [law enforcement] officers or agencies perceive and interact with black community members and suspects.” Perceptions determine quality-of-life outcomes in a racialized society.

Perceptions are symbolic guides that specify the norms for our responses to one another.

For Christians, it may help to consider the CDC’s claims about perceptions in this way. Black demographics within a white racial imagination are lives that represent the passion of Good Friday—instrumental suffering and death—while the idealized white demographic is Easter morning, “risen with all power.” Here we see two separate cultural iterations of Jesus within the lived experience of a society where race so profoundly determines life outcomes and possibilities. It is impossible to have one without the other. Black is an (im)moral status, and black suffering is imperative to realize the life of the Risen One, to whom all power in heaven and on earth has been given.

As Bonhoeffer advocates the Christian imperative of vicariously appropriating another’s sin and suffering, he unwittingly sanctifies the condition of society’s scapegoated, Good Friday people, who have no choice in suffering. Choice is a privilege of status that is not afforded to those who are relegated in the sacred hierarchy of human difference. To encourage them to see their suffering as righteous obedience to God in Christ is to sanctify a perpetual social death. Without Christian practice interpreted in this manner, there is little glory in supremacy.

Mike Brown as a Symbol

These problems with forgiveness are not part of common conversation. Rather, they are implied, and they are lived. We see them when we look at Mike Brown Jr.’s death and the surrounding events: He was killed while walking with a friend on a neighbourhood street in Ferguson, Missouri. The residents who witnessed the horrific scene were further traumatized as his body was left lying in the street for more than four hours, inescapably within view for anyone who ventured outside.

Competing accounts of Brown’s actions preceding his death are as polarized as partisan politics in the United States, and they track largely along racial and political lines. Dorian Johnson was the friend walking with Brown when the incident took place, and his account of what happened is a sharp departure from that of the officer who claimed to have fired in self-defence at an unarmed teen who was running away, wounded. For those who remain upset about what happened in Ferguson ten years ago, it is implausible that Brown was of any real threat when he was finally shot to death in a volley of bullets, at a distance, unarmed. Those who support the officer see things differently—Brown’s death makes perfect sense. But in truth the details of that moment are more complex than the facts that are disputed across the racial and political divide. What mattered was people’s perceptions of Mike Brown—that is, the expectations that his living body elicited from his community and the officer who killed him. In a society with histories that function as interpretive tools for current realities, Mike Brown’s body was a symbol occupying a place in a racial order and carrying meaning beyond what he knew of himself or could possibly control. Mike Brown, the living symbol, meant something nefarious to the armed representative of the state.

Eyewitnesses in his black, north St. Louis community described Brown as a “boy.” He had just graduated from high school and was anticipating the day that was fast approaching when he would say goodbye to his family and community and head off to college. And though he was larger than many within his peer group, like them, Brown was still seeing a pediatrician. Dorian described him as “a friend.” Dorian’s friend was wearing basketball shorts on that fateful day, which meant that he had no pockets in which to carry a weapon. Indeed, Dorian recalled that his friend, Mike Jr., was frightened and angry that they were being fired on while unarmed—and he was in the process of calling out for the officer to stop shooting before the final, fatal shots were fired. But the officer who killed Mike Jr. saw something very different. The officer described him as “a demon,” a tormenting evil spirit from the abode of the dead, charging him with intent and ability to destroy him with his bare hands. Perceptions are symbolic guides that specify the norms for our responses to one another.

Forgiveness as a Guide

As Bonhoeffer and others indicate, the prominence of forgiveness in the Christian story makes it normative for our social life together. It, too, serves as a guide. At this point I want to highlight the fact that Christianity in the United States is also a cultural possession of the West in general and is embedded within the larger history of our national life together. When we think through forgiveness, we are not only considering its meaning to those who self-identify as Christian; we are also discussing a religious expression that is latent within our national and civic life. Even in this iteration of religion in the political life of the nation, forgiveness is a guide, connected to the doctrine of salvation, and it influences our life together. It is present in the yearning for an ideal society that results in the disproportionate number of blacks dying at the hands of law enforcement. It is the claims that go unuttered, written on bodies as aesthetic signalling systems, read by our basic convictions of human worth and acted on as moral norms.

When we think through forgiveness, we are not only considering its meaning to those who self-identify as Christian; we are also discussing a religious expression that is latent within our national and civic life.

Within a racialized society, our interpretation of forgiveness is informed by the social, cultural, and political content that mediates reality and the meaning of redemption to us. In moments of racial distress, forgiveness becomes a reflex response that serves the social maintenance of racial hierarchy. It is a pre-conscious stimulus that emerges within the ideal of American exceptionalism, the “city on a hill” that is a light to the world. J. Kameron Carter describes this practice of forgiveness as ritual within what he names “the religion of whiteness”:

Forgiveness (as a ritual) functions publicly, to script roles around blackness and death within a society organized around whiteness as the sign of proper life, or the life that is properly human. In this context, police violence and forgiveness rituals work to secure the common good and civil society. They work to secure America as a project of religion. Such religion may be thought of as “the religion of whiteness.”

Carter further explains how this American Christian civil religion, whiteness, operates after racial distress. Whiteness turns to rituals of forgiveness that are necessary from those who are structurally positioned as black to redeem the ideal of the nation as a beacon of equality and freedom. Said differently, in the wake of unarmed black death, black forgiveness reconstitutes the trauma to reify the ideal of American liberty and justice for all. Black anger at injustice is untenable; only forgiveness will save the social order.

Ironically, in such moments of racial distress, this ritual practice of forgiveness is a two-edged sword. It is an imperative for those structurally relegated by whiteness to maintain the ideal of a just, Christian society, while it is simultaneously a thing demanded by a white society against that same relegated demographic. The awful thing isn’t spoken aloud, but it is implied as the killer is defended by peers: blacks are malevolent and need to repent. And all the while there is no possible repentance that would undo the perpetual malice associated with the structural position of black people in a racial hierarchy. There is no forgiveness for being black, as that space is needed for the white ideal to be legible to itself. Forgiveness becomes a ritual for the redemption of the civil religion of whiteness and simultaneously a lethal weapon of that same religious order.

On the evening of the tenth anniversary of his son’s death, Mike Brown Sr. said it best when referring to his pursuit of justice for his son: “No one wants to see an angry black man; they’d rather see us in tears,” which is to say, contrite within his place and not demanding something different. Brandt Jean, the brother of Botham Jean, performed this ritual impulse in court with the officer who shot Botham to death as he sat watching television and eating ice cream in his own apartment. Brandt stepped down from the witness stand after declaring forgiveness and held the killer in his arms. Relatives of the nine members shot to death by a young, self-avowed white supremacist during weekly Bible study at Mother Emanuel AME in Charleston performed the ritual on a day that their loved ones’ killer appeared in court. One after another they declared their forgiveness, including their desire for the killer’s well-being. To be clear, I do not judge anyone’s chosen response to their family’s most tragic moment, nor their intent to understand the meaning of their deepest-held convictions under duress. Rather, I simply want to highlight how the common ritual of forgiveness works in moments of racial duress. Police in Dallas rewarded Brandt Jean’s affirmation in his tender moment of forgiveness as he also sought to demonstrate that not all black people are dangerous. President Obama declared that their statements of forgiveness demonstrated how the members of Mother Emanuel AME represented the “decency and goodness of the American people,” which, like Brandt, also affirmed the national apparatus. What if forgiveness meant much more than this?

Turning Toward Cone

For centuries black people have had the enduring task of thinking through the meaning of the Christian faith in the context of duress. What does Christianity mean to those who are structurally relegated and harmed? Forgiveness on its own can be a harmful guide when it serves to sanctify the political apparatus derived from human hierarchy. In his magisterial text God of the Oppressed, James Cone argues that forgiveness is not the problem; rather, the problem is typically those who are asking that blacks perform it:

They who are responsible for the dividing walls of hostility, racism, and hatred want to know whether the victims are ready to forgive and forget—without changing the balance of power. They want to know whether we have any hard feelings toward them, whether we still love them, even though we are oppressed and brutalized by them.

In other words, those at the top of America’s status hierarchy need assurance that the world of liberty and justice for all is yet operational in the face of the obvious violence of black suffering. Justified death, or black forgiveness, makes that operational status possible.

In his theological considerations of these tragic dynamics, Cone links forgiveness with reconciliation as the point of departure for recognizing the meaning of the gospel in racial duress. Forgiveness becomes a matter of reconciliation in an overall work of liberation that God accomplishes in Christ. Liberation is the work of the gospel and the mission of the church. Cone emphasizes the way of Jesus as the way of justice, which is to say that God has preference for the poor and oppressed. For some, the claim that Jesus is for justice asserts that Jesus is not loving, as justice would mean that we get what we deserve and are not forgiven. Hence, there is no justice in the way of Jesus, only love and forgiveness. Against this Cone states,

A black theological analysis does not spiritualize Christ’s emphasis on love as if love is indifferent to social and political justice. We black theologians must refuse to accept a view of reconciliation that pretends that slavery never existed, that we were not lynched and shot, and that we are not presently being cut to the core of our physical and mental endurance.

For Cone, forgiveness must lead to a new relationship with people created by God’s concrete involvement in the political affairs of the world, where God “sides with the weak and the helpless.” Forgiveness is inseparable from reconciliation, which is a term that speaks to sin as a social category. To be in Christ and reconciled to God is to be on the side of justice, doing the work of rectifying relationships that are distorted by practices of abuse and domination.

Another Way

In this extended reflection on the killing of Mike Brown Jr., I have endeavoured to demonstrate how old ideological harms within our national narrative are preserved as religious practice in our unexamined life together. We see this most clearly with the Christian doctrine of forgiveness, which is burdened with the histories of social and political ambitions that are unrelated to the gospel of reconciliation. It is only with honest and unavoidably vulnerable reflection that we may unburden ourselves of the histories that embed our sacred convictions and prohibit the possibilities for healthy life together.

Forgiveness is crucial to the maintenance of a healthy political and civil life. But outside its public function, we must seek it and perform it in the maintenance of intimacy with one another, and for our personal well-being. In relationships, we can give only from what we have to offer, and forgiveness is the acknowledgement that what some have to offer does not serve the efforts of healthy connection. When we forgive, we refuse to allow dysfunction to dictate how we view ourselves and relate to others; we decline to receive or hold on to acrimony from those who have only that to offer us. Honest reflection acknowledges that I, too, have given what I did not intend to give, and would rather take it back and offer something more meaningful instead. Some may not be capable of such honest self-reflection, and in the absence of that ability from an offending party, forgiveness means that we choose the healthier possibility for ourselves by not becoming a repository for someone’s acrimony. The demand for justice includes this ability—the acceptance of right relationships and the healthier social content that accompanies them. In Ferguson, within the nation, and at home, to forgive is to choose a better way to live together, and to remove the obstacles that prohibit our ability to connect with one another in healthy relationships.