T

Is it possible for peace to walk in power anymore?

The events of October 7 have left me haunted by this question. The horrors of that day for Israel, followed by a retribution that will scar generations of Palestinians, are a living hell. Inhabiting the Christian faith an ocean away feels weak, ponderous even: a prayer-for-both-sides kind of luxury. What does our Lord require of his followers in times like these?

Call it tragedy or providence, but just before Hamas terrorized Israel, I had determined it was time for Comment to explore the dynamics of violence in our own society. Not because violence is anything new, but because it seems to have grown into an untreated tumour in the North American headspace: dominating our news feeds, lurking behind our big decisions, striking the public spaces—schools, grocery stores, bowling alleys, music festivals—whose repeated massacres ever more deeply traumatize the public square that Comment labours to heal. Humans properly fear violence, all forms of it. But what feels like a less healthy development is how much violence itself—avoiding harm or threatening harm—is dictating the norms by which we negotiate a common life.

Some of this is a legitimate response to current realities. Large-scale wars are being waged in Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan, and Myanmar, destabilizing our sense of security. Closer to home, I no longer select a melon in the produce aisle without turning my head every few seconds to gauge an escape route should gunshots ring out. Our richest and most unequal cities have suffered an exodus: the second most common reason cited by those leaving Seattle, Washington, DC, New York City, and San Francisco is safety and security. For those trapped in neighbourhoods long scourged by poverty, racism, gun violence, and drugs, the days are distorted by ever-present danger.

We have become addicted to threat perception, forgetting the skills and dispositions required to imagine a more generous peace.

But some of our obsession is narrative-driven. As the white blood cells of a healthy society disappear—loving communities, trustworthy leaders, and everyday kindness—our individual ability to weather turbulence also frays. We start to crave a story with clear villains and victims, and we start trading in predictions. Sooner or later, we find ourselves standing at the edge of anticipated apocalypse, feeling alone yet somehow collectively petrified. Eight out of ten Americans believe that the United States faces a threat to its democracy. Since 2021, one in four have come to believe that political violence is justified to “save” the country.

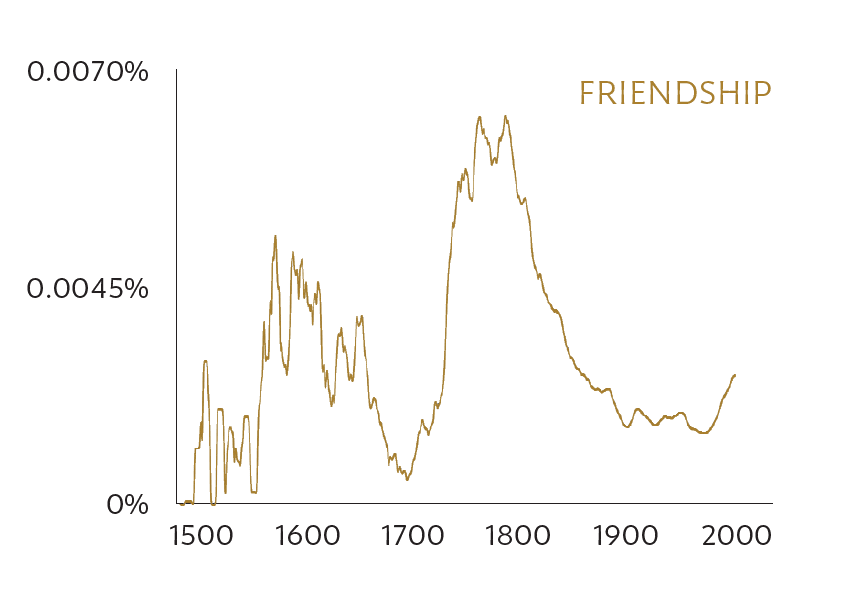

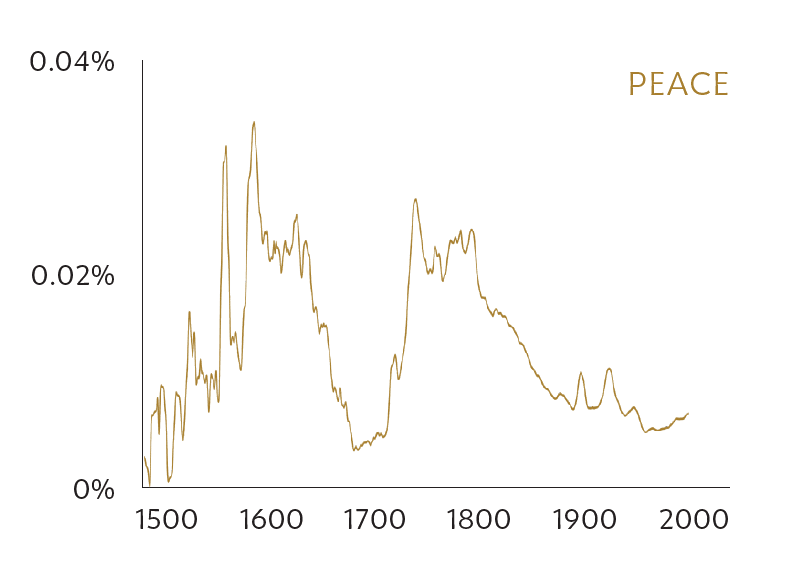

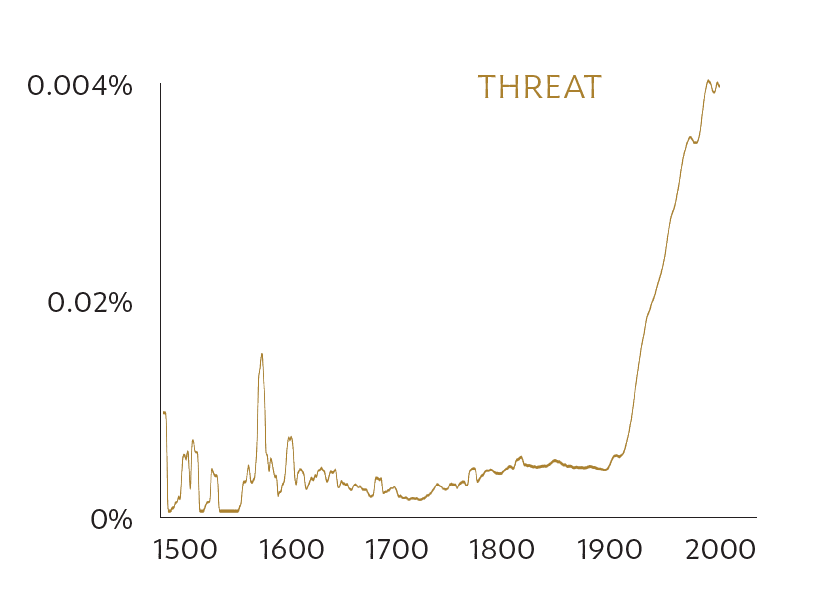

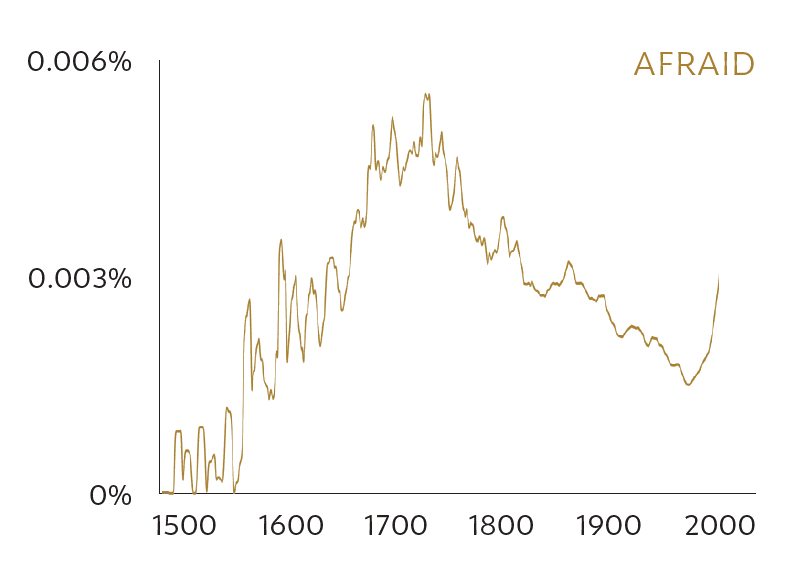

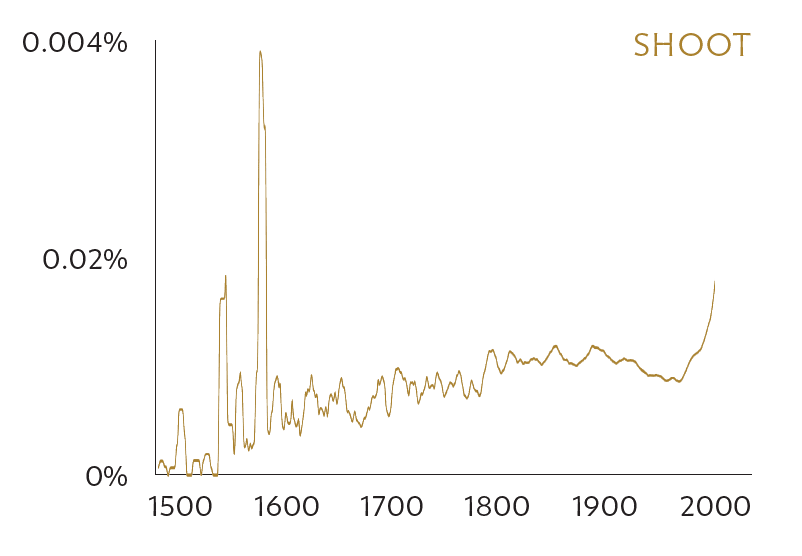

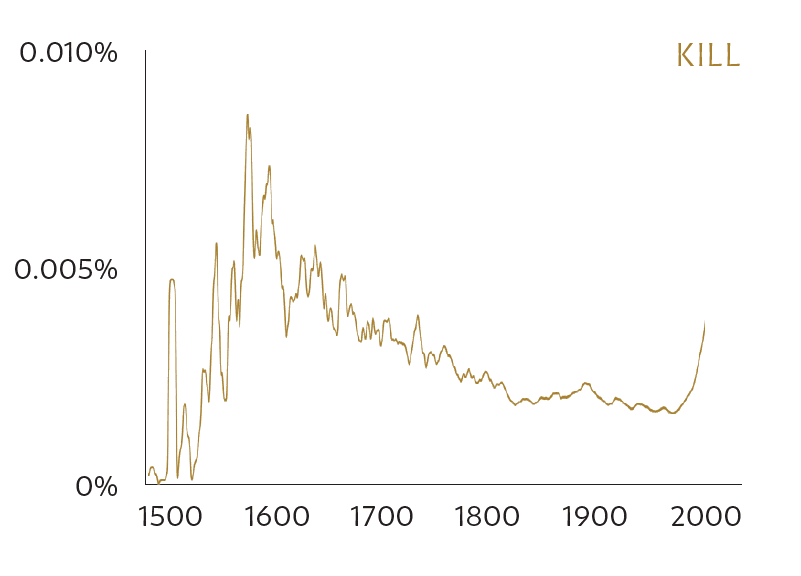

It’s like everyone is walking around with untreated PTSD. We have become addicted to threat perception, forgetting the skills and dispositions required to imagine a more generous peace. We fight over idols like “protection” and “safety,” staying sufficiently vague about what or who is at stake until our own back is against the wall. Two-thirds of Americans now own a gun or could see themselves buying one in the future, 72 percent of them explaining that they feel an increased need to protect themselves. When members of Gen Z are asked, “Can other people be trusted?” only 19 percent say yes, while 51 percent say that “some people deserve to be cancelled.” Words connoting trust and harmony are down in historical use, while words depicting paranoia and violent acts are spiking.

Ngram Graphs, 1500–2000

Is there a way out? This issue was born out of that question. And while I think the answer is yes, the path to get there is an important pilgrimage. I hope this issue arrives as a sherpa you can trust, one whose traversing through the dark night abroad and the dreaded day at home illuminates the paths, not to war, but to renewal.