Theologians have no special experiential knowledge of the terrain of death, though we are often asked to comment on it. The questions I am asked are often very particular ones about the living conditions of our future abode. The thing is, the Bible is actually quite minimalist in its account of the life to come. We are told of “pearly gates” (Revelation 21:21) and “many rooms” (John 14:2), of a place of “no more death or mourning or crying or pain” (Revelation 21:4), but this is not nearly enough for those of us who want more details. We want first-hand knowledge from a person who has been there and can describe the interiors. The problem, of course, is that those people who have been there cannot return. The door once closed is sealed tight.

Mormons have cornered the market on descriptive real estate in the celestial city. The Book of Mormon famously teaches that “families are forever”; the lives that we build for ourselves will continue seamlessly in the lives to come. Our children are returned to us and we rule with our spouses, populating a home similar but perfected, different from our current lives only in duration. This vision is not without problems: what happens, for instance, if one spouse dies and a second is added? Who gets to be married in the next life? And yet it is not surprising that this vision is compelling. I’d love nothing more than the promise of my children around my table forever.

In his book The End of the Christian Life, Todd Billings describes a Christian vision of the life to come that is more than an extension of our present happiness. The problem of death is not simply of happiness’s interruption. Billings is one of those who has had to learn to live with death, or perhaps it is more accurate to say that he has had to learn to live while dying. Diagnosed with stage 4 cancer in his late thirties, Billings writes of his presence in this strange land of medicalized death and dying. He and other late-stage cancer patients are a new breed created by the accomplishments of modern medicine. Ten years ago such patients did not exist. But now, with the cooperation of chemotherapy and genetic technologies, those who would certainly have died may now live with the knowledge of their certain death. It is a gift of a sort, but not one without strings attached.

There are at least two models for living after the knowledge of one’s imminent death. The first is the “live like you were dying” model that encourages “sky-diving” and “Rocky Mountain climbing,” as if terminally ill people had gobs of pain-free time and bank accounts untouched by medical bills. The second is of the patient curled up on himself, settling in at home to die quietly without troubling anyone else. Both of these reflect the self-centredness of a culture that assumes death is largely about resources. You either avail yourself of pleasure, or you ensure that you require no resources from anyone else. If pleasure is life’s currency, then death has no place in the economy. It is best to deny death as long as one can, and then get on with it quietly.

If pleasure is life’s currency, then death has no place in the economy.

With terminal illness there are at least two kinds of loss. There is losing what you love, the grief exacting in its puncture, marking a wound that will always remain. And then there is anticipated grief, the feeling that you will lose what you love but haven’t lost it yet. You cannot cauterize this wound. This one you live with. It remains as long as you do. Anticipated grief, this knowledge of loss that you haven’t lost yet, is a companion but never a friend. It is the narrowing of options, the sound of a door closing.

My one wish for death is not to see it coming. Death, you see, will be the end of me—if it occurs quickly enough, I will not have to contemplate my end. The heaviness of grief is doubly so when you must contemplate it and see in a glance what you will lose (a child, a beloved) and what they will lose (you). It is my loss, but also theirs, that would accompany every waking moment. To die having not lived with that would be much lighter.

Though he writes about the pain and grief of his own illness, Billings does not dwell on these losses. Rather, he tries something difficult and sorely neglected in modern theology, which is to quietly unseat pleasure as life’s currency in order to speak rightly about death. The book itself is somewhat eclectic, discussing the prosperity gospel, the Old Testament tabernacle, and near-death experiences. Billings’s chief concern, I think, is this shift of priorities. What he is trying to unearth is the seat of Christian hope. The problem with much of the hope professed by Christians, he writes, is that it is neither Christian nor all that hopeful. It is a hope that is continuous with modern, secular concerns—a hope that seeks to articulate an eternally extended pleasure. It wants the pleasure that we know now, just more of it. And just as there is nothing uniquely Christian about this hope, there is nothing uniquely Christian about this view of life and death.

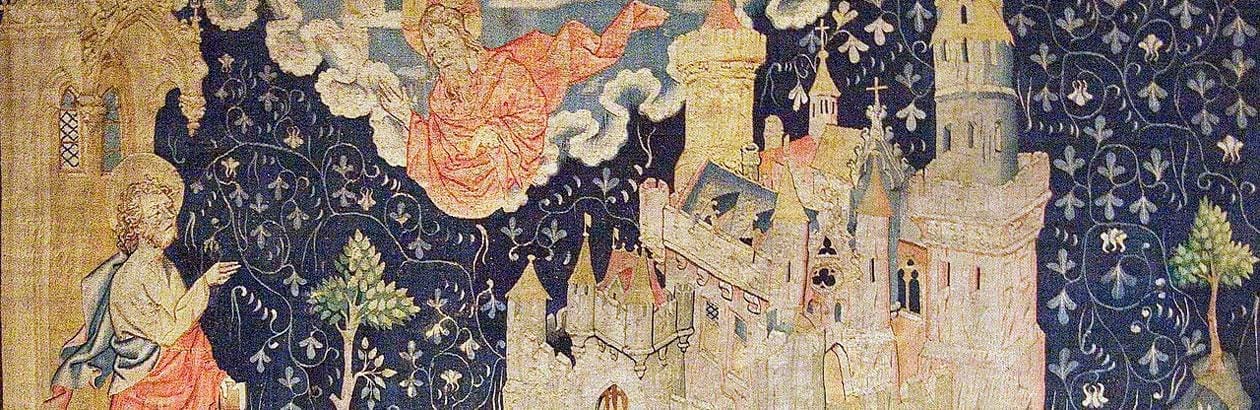

In highlighting this contrast between modern, secularized hope and true Christian hope, Billings works with two chief images of the life to come: the family reunion and the temple. He is rowing us away from the former and toward the latter. This is hard work indeed.

The problem with much of the hope professed by Christians is that it is neither Christian nor all that hopeful.

Witness the family-reunion vision of heaven, the vision that is operative for many Christians. In this picture we are reunited after death with those we have lost, meeting them after our death as they were when we lost them. Billings writes that this image looms large in the cultural imaginary. He quotes the service for George H.W. Bush, in which family members expressed hope for his reunion with his lost daughter Robin, the one “who he’ll see first.” Billings writes that even in a culture where religious belief is in decline, such a view populates the cultural imaginary. An attempt to “mend our stories,” this hope for reunion with those lost is shared by Christians and non-Christians alike.

But again, even if we work to reconcile these chronologies, Billings would have us know that if our only hope for the life to come is found in reunion with those we have lost, what we have is not really Christian hope. Rather “Scripture speaks about the age to come as a theophany, a coming and appearance of God.” In the words of Revelation,

See, the home of God is among mortals.

He will dwell with them;

They will be his peoples,

And God himself will be with them. (Revelation 21:3 NRSV)

Here the family-reunion model is inverted in at least two ways. First, unlike a vision where mortals “fly away” to be with God, Revelation’s vision has God returning to mortals. God “will dwell with them” and make his home among them. And second, the reunion that occurs between mortals is mediated through this initial reunion with God. The distance that humans have experienced from God is removed in that day when God will make his home with us. It is there that we are then reunited with one another.

The language of God “renewing creation,” therefore, is not a metaphor. What God has made will not be cast aside but reinvented from within; this is the logic of resurrection, not making ex nihilo, as with the initial act, but remaking in its intended form. But our hope is often too small to grasp this. As Billings writes,

This coming of God in Christ to renew the creation is the breathtaking Grand Canyon of Christian hope—so wide and deep and expansive that we are left in wonder. It’s hard to take in. And our life stories, which can seem so big when we’re driving on a winter road or when a loved one dies, are tiny, miniscule, like specks of dust in the midst of staggeringly deep valleys, high cliffs, and wide-open spaces.

To truly conceive of Christian hope, Billings wants us to regain this sense of proportion; our smallness and God’s magnitude. Terminal diagnoses can deliver this recalibration, but otherwise our lives recommend against it. Everything in our emotional and cultural experiences recommends against forming our emotional lives to this sense of scale. What we know and love in this life we hold tightly to. Mothers are surrounded with tools to tighten this grip. I take pictures and compile albums. I have purchased monogrammed baby bibs, certain to be quickly soiled. I have eased chubby toddler feet into stark white shoes. I have knit immeasurable booties that slid off and dropped beneath the carriage, discarded for the next walker to find. I have folded and saved tiny dresses that will never again be worn. I set aside cast-off toys and dog-eared board books, longing to be reunited with time that is now lost.

Perhaps only a mother can love more in remembering than she loved in experiencing (infant socks have not always made me weep—for years they were just laundry), but this is the shape that memory takes. It is also I think something innate in us, this longing for the restoration of time. That we are set in time is one of the characteristics of our creatureliness. Unlike God, who is outside of time and so experiences its fullness perpetually, this world is characterized by time’s passing. We deny this reality as best we can, holding on to moments and memorializing life occasions and marking holidays with competitive fervour. And yet the day after Christmas will come; the nursing infant will begin school. Seasons pass and then return again, though different in the next installment. Nostalgia is love of a thing plus the space time has set between you and it. It can be both a gift and a burden as time moves us further away from that child, that mother, that season of life. The love of that object grows deeper as we are distanced from it, and the knowledge that it will never return takes what might be tender and cuts toward the bone.

How do we love something, then, knowing that it won’t always be ours? How can we live as parents and children and lovers in bodies that slouch toward death? How can the Christian curate the gifts of this life and treasure them without allowing their inevitable loss to deaden the senses, to send us toward anxiety and fear? (Is $100 eye cream anything other than denying that eternity is God’s alone?) How can we renew Christian hope as something other than the restoration of mortal things, even good mortal things?

In On Virginity, Gregory of Nyssa makes a surprising argument for virginity that is resonant here. By Gregory’s account, virginity frees the Christian from anticipated grief. Better to be free in this life, and enjoy eternal bliss in the next, than to enjoy bliss in this life that is only a shadow and is constantly plagued with the knowledge of love’s inevitable loss.

Gregory lays it out plainly: “Let us sketch a marriage in every way most happy; illustrious birth, competent means, suitable ages, the very flower of the prime of life, deep affection, the very best that each can think of the other.” All seems well, Gregory writes, for a time; “but observe that even beneath this array of blessings the fire of an inevitable pain is smouldering”:

Whenever the husband looks at the beloved face, that moment the fear of separation accompanies the look. . . . When he marks all those charms which to youth are so precious and which the thoughtless seek for, the bright eyes beneath the lids, the arching eyebrows, the cheek with its sweet and dimpling smile, the natural red that blooms upon the lips, the gold-bound hair shining in many-twisted masses on the head, and all that transient grace, then, though he may be little given to reflection, he must have this thought also in his inmost soul that some day all this beauty will melt away and become as nothing.

The same for Gregory is true for the love of children that marriage brings:

The danger of childbirth is past; a child is born to them, the very image of its parents’ beauty. Are the occasions for grief at all lessened thereby? Rather they are increased; for the parents retain all their former fears, and feel in addition those on behalf of the child, lest anything should happen to it in its bringing up; for instance a bad accident, or by some turn of misfortunes a sickness, a fever, any dangerous disease. Both parents share alike in these.

Marriage and children are so lovely, so desperately precious that they carry with them the knowledge of their inevitable loss. Gregory’s chief argument for virginity, therefore, is that it yields a life free from such premeditation. The virgin can live untethered to anything but Christ. Such a one “is always in the presence of the undying Bridegroom; it has the offspring of devotion always to rejoice in; it sees continually a home that is truly its own, furnished with every treasure because the Master always dwells there; in this case death does not bring separation, but union with Him Who is longed for.” To live with such is to be “fixed on heaven.” Only such a person can truly live as a creature: “You will understand, if you have a comprehensive view of things as they are, that nothing in this life looks that which it is.” It feels like the ultimate thing, but is only a shadow.

If our only hope for the life to come is found in reunion with those we have lost, what we have is not really Christian hope.

Billings rows us toward such a comprehensive view of things. The picture of this new reality is already given shape in the Old Testament tabernacle. The tabernacle was the house of God among God’s people. Concrete specifications that in their ordering symbolized all of creation as the place of God’s rule: The candlestands are heaven’s lights. The array of decorative symbols stood in for nature’s variety. The boundaries of the tabernacle reflect the world’s order into light and dark, water and ground, order and chaos.

“Biblical hope,” Billings writes, “centers on the presence and dwelling of God in a renewed creation. . . . The climax of God’s covenant promise is a great, cosmic encounter with the Lord himself, and a reconciled communion with others flowing from that.” This is true Christian hope: “The final Christian hope, the end of the Christian life, is not life extension or self-fulfillment. It is for God to ‘tabernacle’ among his people—as in the garden, as in the people of Israel—as those united to Christ by the Spirit in the church, culminating in fullness in the age to come.” Perhaps we cannot get to such hope ourselves; our love of this world’s good gifts is too dear. And yet perhaps even the reminder that these loves are but a shadow could remove a bit the sting of death.

We do not have many details of the life to come. The best picture I have is of being somehow present to my children in every moment of their lives all at a glance; to hold again the fresh newborn, the nursing infant, the chubby sticky toddler, the firm hand of a preschooler crossing the street—to have all of this in an instant. I have given them my time, my youth, my ambition sacrificed for presence. To know my children in the plenitude of their lives, as they are now and as they were, to have them back and all the time passed in their presence—this is the best hope I can imagine. But by itself this hope is not Christian enough.

The only way Christian hope makes any sense is if the Song of Songs is read as a symbol, an image of the love between Christ and the church. The Lover beckons, “Arise, come, my darling; my beautiful one, come with me.” So Christ speaks to the soul, to us all. I cannot easily put in order my loves here. I hope that in the life to come my children remain mine, that they know me and I am known to them fully. But I believe too in a risen Lord whose love will place the desires of the heart in stark relief. As Gregory writes, there is an inevitable problem with loving things that you will lose. It is so hard to imagine that it is this married life, populated with children, that is the allegory, and union with Christ in the life to come that is the real. But arise, come, says the bridegroom, and we will follow, to that place where “the winter is past and the rains are over and gone.” The hope of the Christian life is to take such a comprehensive view, to love more the things you will gain.