Memory

It is something that my granddad has lost. His memory is a faint picture, a brief remembrance of that which was. He has dementia. It’s quite a painful thing to watch. There are moments of joy but also moments of sadness. Like that time when I came home to visit and he didn’t know who I was. All of the good times we had seemed to fade away each passing day.

But not all was lost. I asked him recently, as we were laughing together on the couch, “Granddaddy, do you still got your dance moves?” He paused, as one trying hard to travel down memory lane. He rubbed his bald head, looked at me in a way that spoke more than words. “I don’t know. But I’m still here.”

I’m still here.

That struck me. He may have lost some things, but he’s still here. That is our story. Our black story. The story this nation, and its people, have tried to steal from us. We have lost, but we remember. Maybe that is why memory is so powerful: it is the unbreakable cord that binds the pains of the past to the problems of the present and the possibilities of the future. Memory has a particular way of allowing us to ponder the actual and imagine the possible.

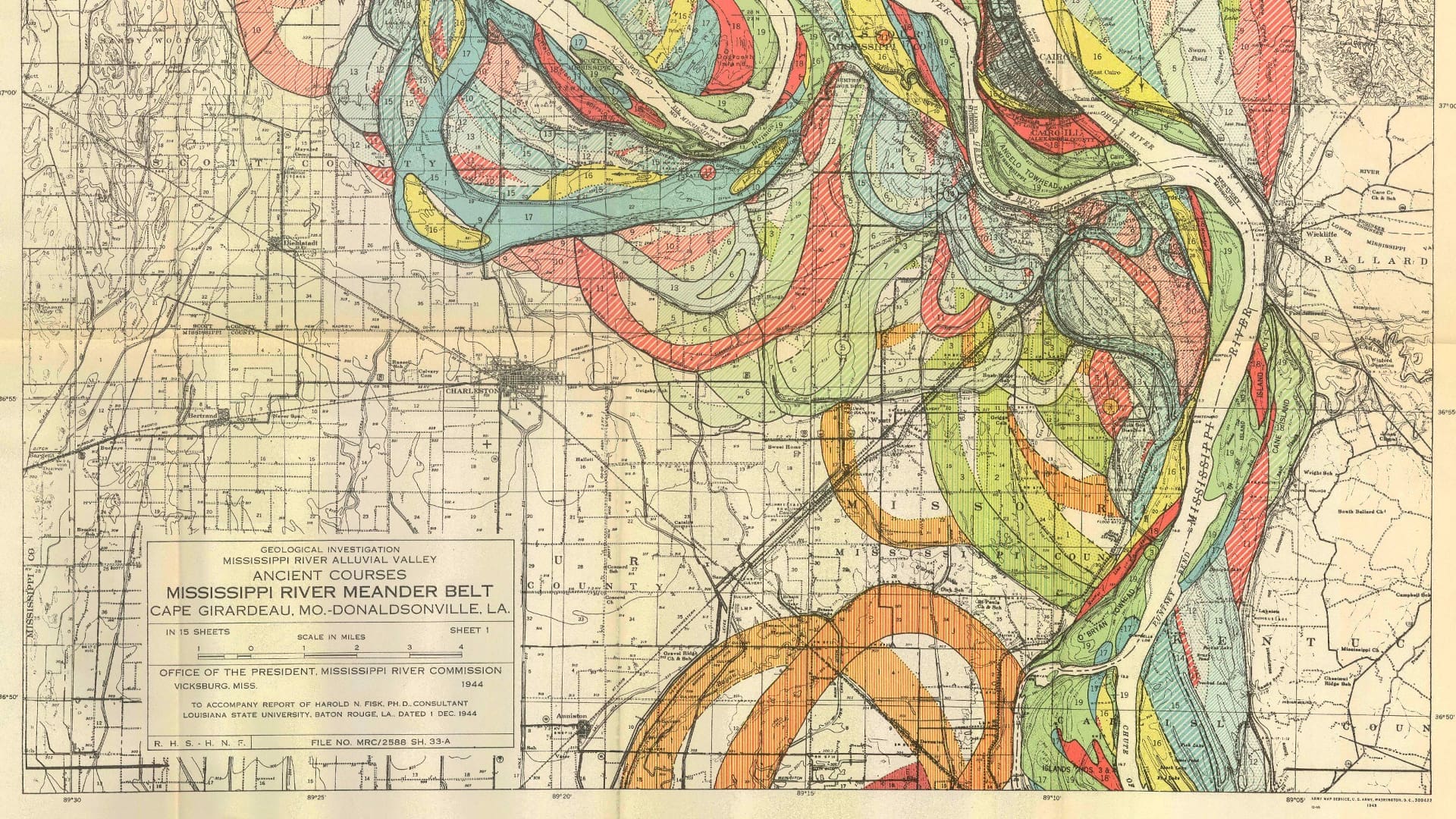

Writing in her beautiful reflection The Site of Memory, Toni Morrison says that “the act of imagination is bound up with memory.” She recounts how the Mississippi River was straightened out to make room for houses and livable conditions. From time to time, the river floods these particular places. Morrison stops and examines the word “flooding.” What is happening when the water comes over the banks is not flooding, she says; “it is remembering, remembering where it used to be.” All water “has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back where it was.”

Morrison takes us back to the memory of black people’s literary genius. Out of the imagination, they dreamed of a new world. They told a story of the dreams and hopes of those who are bound simply trying to get back to where they were. Through many toils and dark nights of the soul, a people dreamed of a better day of freedom—a kingdom of peace where the souls of black folk can be free.

She remembers the story of Olaudah Equiano’s adventure-packed narrative. She remembers Harriet Jacobs’s story of quiet desperation. She remembers the political savvy of Frederick Douglass and the honest vulnerability of James Baldwin. All of these black folk told stories of hope in the midst of despair, anger in the midst of oppression, power in the midst of pain, love in the midst of brutality. And this rush of imagination, Morrison writes, “is our flooding.”

We return again and again to that flooding, the stream from which we have come: a people’s journey, a nation’s story.

History

History that becomes witness is history that shapes the paths of the living, bound up with their heartbeats and their breathing. Witness reveals the telling of history without false pretense of history for history’s sake. Witness is history being honest about its wishes.

—Willie James Jennings

We remember Auschwitz and all that it symbolizes because we believe that, in spite of the past and its horrors, the world is worthy of salvation: and salvation, like redemption, can be only found in memory.

—Elie Wiesel

As I sit at my computer this morning, it is February. It is Black History Month. It is a time in which we once again tell the story of black resilience and resistance, endurance and engagement, suffering and sacrifice. It is a time where we pause, we hear. We remember.

In the New York Times’s 1619 Project, Nikole Hannah-Jones writes, “Black Americans have been, and continue to be, foundational to the idea of American freedom.” On the four-hundredth anniversary of Africans arriving to this land as slaves, she makes the case that “it is we who have been the perfecters of this democracy,” that black Americans have pushed toward the country’s ideals despite their circumstances.

I’ve heard it said by Daniel Migliore that history is a “dangerous” memory. It never lets us go until we attest to the wounds and commit to healing. It presses on us that piercing but powerful word: love, love, love. Love never quite lets us get away with our forgetfulness, our disregard of how power has been abused, and our ethical commitment to change.

Maybe that is what makes history so powerful. It tells of struggle. It is always being woven in front of our eyes, always inviting us to perform a world, to dream of a reality.

Willie James Jennings, professor of theology at Yale Divinity School, writes that the goal of telling history is not simply being a historian or thinking historically. Rather, we must see “a past unfolding in a future and making intelligible the present.” The goal is historical consciousness. This consciousness “does not romanticize the past.” It is keenly “aware of suffering and those who cause it, and it also sees God working toward the good in the midst of pain.” The history of the past always bears witness in the present.

What is the aim then? Jennings writes that it is simply: witness. History that becomes witness “is history that shapes the paths of the living, bound up with their heartbeats and their breathing.” This witnessing, this telling of a story long remembered, is “being honest about its wishes.” It is a being honest about the history that we enter, a history we tell, and a history that we realize.

As Elie Wiesel wrote of the memory of Auschwitz that resides deep in his bones, black Americans too remember the memory deep in our bones of life in America. One cannot speak of being black and being American without being forced to deal with the complexity of such a paradox. This ever-present “two-ness,” a warring between the selves, that W.E.B. Du Bois speaks of is the shadow of a past that we have tried to forget. One of the crucial things to see is that black history, as with Israel’s story in the Bible, takes place in diaspora.

Jennings writes that “diaspora means scattering and fragmentation, exile and loss.” It means a longing, a searching for a place to be, a place to stand. Though we have pushed the country in the pursuit of its highest ideals, it is done in the soil of forced migration. This life is a life “crowded with self-questioning and question for God concerning anger, hatred, and violence visited upon a people.” This should not escape our attention. In our people’s sojourn in this strange land of America, we remember the story of loss. We are striving not simply to be perfecters of democracy in America, but to obey the command of Christ, and be the perfecters of Christian love in the church in this desperate land.

For many, this story has become a myth of progress. A symbol of the progress of America, particularly white America, to finally “get it.” To finally stop hating black people enough to afford them the opportunity for that great triple promise of the democratic creed: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Jeanne Theoharis captures the heart of this myth. As she reflects on how we remember black people’s struggle in America, she writes that “a movement that had challenged the very fabric of US politics and society was turned into one that demonstrated how great and expansive the country was—a story of individual bravery, natural evolution, and the long march to a more perfect union.” The re-narration suggests that racial injustice, Americans’ original sin and deepest silence, “derived from individual sin rather than from national structure.”

Thus the progressive and expansive vision of the black freedom struggle became passive and privatized. The dream, diluted and distorted. Stripped. Silenced.

I have often thought of the night James Baldwin heard of the death of his friend Martin Luther King Jr. As he sat by the poolside, the phone rang. It was the news of tragedy. Martin was dead. He wept bitterly. Then, finally, he entered into a shocked and helpless rage. For years, Baldwin would try to forget that night. “It’s retired into some deep cavern in my mind.” But he still remembered. Though the nation would try to wash Martin and the history of the black freedom struggle away, James held on to what little piece he had: memory.

In truth, that’s all we have.

The memory of a dream. But memories are not powerless, as Morrison has already reminded us and as Baldwin likewise expresses: “Intangible dreams have a tangible effect on the world.” And diaspora life is not simply loss but also power. It is the power of a conviction to survive and the power of a confession to never yield to the forces that would destroy them. This life is life by any means necessary. It is a faith that God will bring hope in the midst of the worst of circumstances. It is the audacity to survive.

Even if we don’t have all the answers now, we must bear witness. We must tell our story. As Cheryl Townsend Gilkes, writes, “We are here because we believe we have a story to tell to the nation, and our experience has something special to say to the world.” Our language and storytelling have a way of helping us in the dark. In a time of religious, social, economic, and political chaos, it seems critical that we sit at the feet of these stories of freedom.

So we remember history. We remember our striving.

We believe with Elie Wiesel that “in spite of the past and its horrors, the world is worthy of salvation: and salvation, like redemption, can be only found in memory.”

Terror

American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.

—James Baldwin

In that era, the lynching tree joined the cross as the most emotionally charged symbols in the African American community—symbols that represent both death and the promise of redemption, judgement and the offer of mercy, suffering and the power of hope.

—James Cone

One cannot speak of memory and salvation, history and hope, without visiting one of the most devastating periods in American history: racial terror lynchings.

After slavery was formally abolished, writes the Equal Justice Initiative, “lynching emerged as a vicious tool of racial control to reestablish white supremacy and suppress black civil rights.” More than four thousand Americans were lynched across twenty states between 1877 and 1950: that is fifty-five murders per year. The effects of this can still be felt in the present day. Baldwin was right to conclude that American history is “longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.”

In our day no one has narrated the theological importance and implications of this era better than the late black theologian James Cone. In his book The Cross and the Lynching Tree, Cone writes, “The lynching tree joined the cross as the most emotionally charged symbols in the African American community—symbols that represent both death and the promise of redemption, judgement and the offer of mercy, suffering and the power of hope.” Both the cross and the lynching tree represent the heart of paradox: the worst in human beings and the refusal to let suffering have the final say.

The lynching tree presents a deep challenge for Americans. It is an era that many feel but cannot speak of. When one has been raised in a place that believes itself to be exceptional, to be the moral leader of the “free” world, it is quite easy to forget from whence we came, to forget the cries of blood from the ground. This does not present a challenge for Americans in general. Cone felt this presented a particular challenge to black people and our theology: to explain from the perspective of history and faith how life could be made meaningful in the face of death, how hope could remain alive in the world of Jim Crow segregation.

At no time, he writes, was this more difficult than the lynching era. The lynching tree is “the most potent symbol of the trouble nobody knows that blacks have seen but do not talk about because of the pain of remembering—visions of black bodies dangling from southern trees, surrounded by jeering white mobs—is almost too excruciating to recall.” The sufferings of black people did not end with emancipation but took on different forms and means to achieve the same goal: the oppression of black people.

In 1915, The Crisis, a newspaper that chronicled lynchings, recorded the horrifying story of the lynching of Thomas Brooks in Fayette County, Tennessee. Hundreds had gathered. Camera clicks abounded. People came from far and wide, in automobiles and carriages. School had been delayed, routines stopped, just so that young boys and girls could view the trophy to which their people flaunted their “authority”: the lifeless “corpse dangling at the end of the rope.” The dream of freedom hung in the balance at the horror of the “nightmare worse than slavery.”

These lynchings, Cone writes, were “the white community’s way of forcibly reminding blacks of their inferiority and powerlessness.” This claim was not simply social but went far deeper to the psychological and religious. It was a sort of voyeurism and fanaticism. It was grounded in “the religious belief that America is a white nation called by God to bear witness to the superiority of whites over blacks.” This symbol of the lynching tree meant fear, terror, horror.

One cannot speak of these senseless horrors of yesterday without speaking in the same way of the terror visited on many black children, women, and men in our country who have become hashtags.

In an essay titled “Cries of the Unheard: State Violence, Black Bodies, and Martin Luther King’s Black Power,” Darrius Hills and Tommy Curry simply state, “They were murdered . . . all Black Americans. . . . All dead at the hands of police.” In response, #BlackLivesMatter became the theological and political “demand for Black personhood.”

“No Justice, No Peace.”

“No Justice, No Peace.”

“No Justice, No Peace.”

These were the cries of many of our young black people as they sought to give voice to the deep pain and disappointment that reverberated throughout the nation. Black blood cried out from the ground. Hashtag after hashtag.

Looking back over the time, experience, and the making of a movement, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor simply asks, “Five years later, do black lives matter?” In the five years since Mike Brown Jr. “was murdered and the streets of Ferguson, Missouri erupted, police across the United States have killed more than four thousand people, a quarter of them African American.” Whether we believe they were justified or not, we cannot deny the absurdity of what these lifeless children, women, and men mean to our public memory. These experiences of modern racial terror in our country were never just about abusing black and brown people, Taylor writes. It has always been “a means by which the most powerful white men in the country have justified their rule, made their money, and kept the rest of us at bay.”

As the body count rose, there was horror. “Black bodies bled in the street with such regularity,” writes Barbara Holmes, “that it took our collective breath away.” It seemed all the young people had were their bodies and their cries. Our bodies. Our cries.

Many would like to believe that our lives and our deaths do matter; but if one is honest, it is quite clear that there is what Eddie Glaude calls the “value gap.” The structural principles, policies, and practices in America that make this value gap a reality bear witness in our belief that black lives are less valuable than others. Inequalities in power, wealth, education, health, income, and incarceration bear witness to this ever-increasing gap. Taylor writes that the crisis goes far beyond these statistics of inequality. Deeply ingrained in the American psyche are “stereotypes of African Americans as particularly dangerous, impervious to pain and suffering, careless and carefree, and except from empathy, solidarity or basic humanity.” The living memory of this narrative of racial difference and white fear still lives with us today. We can feel it in the air that we breathe, though we don’t like to believe it: it’s killing us, all of us. We are living in one nation but in two Americas.

The question Cone wondered, and which is before us today: How did black people survive such unspeakable horrors?

They remembered.

Memory, history, were their weapons of resistance. The living memory of the crucified Messiah that lived deep in their bones was and is profoundly real in the souls of black folk. As Miroslav Volf writes about remembering rightly in a violent world, “To remember a wrongdoing is to struggle against it.” To be black and to be Christian is to remember the brutality of our experience and the brilliance of our resistance. It is to remember, as Cone writes, “God’s message of liberation in an unredeemed and tortured world.”

Christ crucified “manifested God’s loving and liberating presence in the contradictions of black life.” This memory empowered black folk to realize that ultimately in God’s future, they would not be defeated by the world’s horror or terror. Despite such terror blacks refused to let joy be completely squeezed out of their lives in the midst of “the white man’s dehumanizing disregard for their humanity.”

The more they struggled, the more they saw the connections between the cross and the lynching tree. It represented what the Greeks of old would call a figura: a reflection of the solidarity of Christ with the crucified of the world and a projection of loving resistance in the midst of violence. If God’s revelation in Jesus is found among the crucified of the world, Cone writes, “then God is also found among those lynched in American history.”

As the cross is a paradoxical religious symbol that inverts the world’s value system with “news that hope by way of defeat, that suffering and death do not have the last word,” so the lynching tree inverts the American value system. It inverts it by actually forcing us to deal with what we have long denied: that black people are actually right about our suffering and that we have refused to allow the world in which we are bound to stop our song.

The final word about black life in America was not death of the lynching tree but redemption found in the cross. The cross was God’s critique of power—white power—with “powerless love, snatching victory out of defeat.” Cone powerfully writes that the lynching tree is the metaphor for white America’s crucifixion of black people. Yet God took the evil of the cross and the lynching tree and “transformed them both into the triumphant beauty of the divine.”

If America, and the church, has the courage to confront the legacy of lynching and the ongoing and ever-present realities of our history that are tethered together, then can there be hope beyond terror.

There can be salvation in our memory.

Life

Breathing life back into the past, pulling from the ranks of your history, is how you build yourself. You are born to something and someplace; you become of a living accord and road. This is how we move forward.

—Imani Perry

As God is directing everything that has happened, does happen, and will happen, God will not let God’s people witness in vain. This is the import of the title “Alpha and Omega,” which John applies to both God and Christ. Ultimately the end is not a place or a time, but a person. History reaches its goal in Christ.

—Brian Blount

There was something about my grandfather and his piano. When I was younger, I would visit their house, walk in, and hear him playing his favourite tune. His feet would be stomping. His head would be bopping. As he played, it was as if he were raptured up in the love of the moment—just him, his piano, and his God. I remember that joy. I remember how deeply it struck me as a kid. Maybe I can attribute my love of music to those early moments.

One thing about my grandfather was that he never wanted to experience it alone. He would always beckon us to come. I would sit beside him. Look at him playing in amazement and start playing my tune as well. There I was: hands going. Feet stomping. Head bopping. Caught up in the improvisation of love. I surely didn’t know what I was doing, and I’m sure it sounded horrible on top of what he was playing, but he didn’t stop me.

He must have known something that I didn’t. He must have known that if I could simply sit, be willing to join, willing to live, but also willing to listen, then one day, I too would make a beautiful melody capable of capturing hearts. I too would invite others into an experience of love.

Image courtesy of Dante Stewart

Though my granddad has lost so much, so much of his memory, so many of the stories that brought us over, one thing he didn’t lose is the tune of love in the midst of such damning brutality. He has refused to give up hope and joy. In those bones of his, the story so deep, is the building of a self, the building of a new reality. There indeed is the possibility of faith in the midst of misfortune, brilliance in the midst of brutality, resistance in the midst of rejection.

This is the place I was born, in the shadow of memory. The memory of our collective struggle. The memory of those who cry no more. The memory of those little babies torn from their homeland never to dance in the ring no more. The memory of the mothers and fathers jumping overboard to escape from hell. The memory of the many bruised and abused bodies. The memory of broken promises and policies. The memory of our beautiful children lifeless in the streets and over social media.

Our memory tells of two stories: one of hurt and one of hope. Not simply for the suffering endured, but also for the resilience and resistance of a people who had the audacity to survive. We are still here. But we are also headed somewhere. As we tell our story, we know, as Brian Blount writes, that “God’s people witness will not be in vain.” Ultimately the end of memory is not a place or a time, but a person. History reaches its goal in Christ.

The question that is laid before me, and all of us today, how will we remember?

In our memory is the imagination of a new world.

In our memory is our salvation.

In our memory is our life.

Header image: Plate 22, Sheet 7, Ancient Courses Mississippi River Meander Belt by Harald Fisk, 1944.