I

It’s no secret that young people these days are skeptical of institutions. Everyone is, according to the data, and members of Gen Z are the most skeptical of all. But is this a hard and fast rejection of the organizations their parents and grandparents devoted their lives to? Or is something else going on?

A curious phenomenon has emerged: members of Gen Z, born between 1997 and 2012, seem to want to join institutions, but only under certain very rigorous conditions. Whereas millennials wanted to bring their whole selves to work, Gen X was focused on salary, and boomers just asked to be able to do an honest day’s work, members of Gen Z (zoomers) want their workplace to offer everything: community, cosmic purpose, radical transformation. Millennials wanted work to allow them to be everything they are; zoomers want their workplaces to be everything they are. Older generations asked their local governments to provide basic services in a timely fashion; zoomers ask their local governments to be embodiments of their national political vision on a micro scale, enacting innovative social justice practices or, on the other end of the spectrum, clear assertions of the value of the family and insistence on work as a prerequisite for receiving social services. Places of worship are under strict scrutiny for consistency with the moral, ethical, and political values of young would-be congregants. And let’s not even start talking about the standards applied to corporations.

A Brittle Idealism

There is a noble idealism present in this attitude toward institutions, but it seems to be somewhat brittle, at least flighty. Recent Harvard graduate Alisa Regassa has watched her peers apply for their dream jobs, which typically involve an inspiring vision of contributing to the world via science or teaching or social entrepreneurship. Then, when they don’t get the post, they switch immediately to lucrative but soulless investment-banking or consulting jobs. “I’ve been surprised that they sell out completely rather than accepting second best,” she says, “especially because the causes they give up on were what seemed to define them completely all four years of college. Like, this is who you were, this is what you were about.” She tells the story of a young man who spent his college years working on an innovative medical treatment and upon graduation applied to work for the lab that develops it. But when he learned he wouldn’t receive an offer, he refused to seek out other, “lesser” labs and instead became a banker. Celia, another recent graduate, reports to me that she’s seen friends win offers at elite law firms but refuse to work for them because they “aren’t abolitionist enough,” in some cases choosing unemployment over work at an establishment that doesn’t meet their ethical criteria. Millennials joined institutions they viewed as ethically imperfect and began to change them when they gained power; zoomers refuse to join institutions in the first place unless they already align with their values.

Social class seems to partially determine which institutions zoomers apply these criteria to. Elite students seek this totalizing belonging and identity in their workplaces, whereas working-class zoomers seek it in voluntary associations, companies they patronize, hobby groups, or other structured social entities. Regardless, the essential criteria appear to be the same. Alisa describes “exhaustion and confusion” with these questions, particularly “how to relate to the System—do you pay the moral price of participating or the financial price of exiting?”

Zoomers appear to be deeply conflicted: they feel a strong pull toward institutions, but also a strong repulsion at anything that doesn’t feel appropriately ethical, pure, communal, or powerful. As Ross Irwin, COO of national collegiate non-profit BridgeUSA and an exceptionally sharp zoomer leader, comments, “They’re looking for a place to put an identity . . . but they’re suspicious, too, so it’s a high bar.” He goes on to observe, “There’s a sense in which people in my generation have no idea what community and purpose actually are, so they’re looking for something that doesn’t quite exist: purpose and community and meaning all wrapped into one.”

Of course, prior generations wanted this too, and institutions have fallen short of those ideals since the beginning. But the way prior generations resolved this challenge was profoundly different: they simply accepted that any given institution existed for a function within a sphere, and that was that. There was less idealism and more diversification: if church wasn’t your jam, you joined the baseball team. If you couldn’t swing a bat, you got involved in the local store. Older generations simply did not ask as much of each institution as these young visionaries.

Why is it that young people crave the specific ballast that institutions offer but seem almost incapable of walking into them and accepting the humble, sensible realities they embody?

And so zoomers often reject the institutions they encounter. Online life, after all, is a series of split-second dopamine hits: flat, pure, fast, and explicitly moral. By contrast, institutional life is slow, complex, and defined by tedious wrestling with the obnoxiousness of being human. On some level, zoomers sense this. They feel the speed of online life and seek something that takes its time; they feel the reductiveness of online life and desire something that honours complexity; they perceive the ephemerality of online life and yearn for something steadfast.

But that doesn’t mean they have the patience to tolerate it. And there’s the rub. Why is it that young people crave the specific ballast that institutions offer but seem almost incapable of walking into them and accepting the humble, sensible realities they embody?

Extrinsic Self, Intrinsic Anxiety

The answer has to do with how they’ve been raised. It is hard to overstate the consequences of the shift, chronicled by Jonathan Haidt in The Anxious Generation, from a “play-based childhood” to a “phone-centric childhood.” A careful understanding of the ways phone-centric life shapes—and warps—the development of healthy inner and relational life provides the Rosetta stone for how young people relate to institutions today. The most obvious shifts have to do with social life. Everyone is laser-focused on social media; nearly all important social interactions are navigated online. Constant engagement is expected, and inaction, not just “wrong” action, is punished. If you don’t “like” your friend’s pro-Palestinian post within the first four hours it’s up, she has the social permission to be upset with you and to publicly imply that you might not be on the side of justice. As John Tomasi, Brown professor and head of Heterodox Academy, puts it, “If I had to describe today’s students in one word, it would be ‘vigilant.’”

Even more damaging, if more subtle, is the effect of phone-based childhood on development of the self. In this intensely digital existence, how you show up online feels almost more real than your flesh and blood. Cole Johnson, lead designer for StoryCorps’s One Small Step programs for college students, observes, “The students I work with seem to have a harder and harder time constructing a coherent internal self.” Today’s experience of growing up involves much more “extrinsic” exploration of identity—engaging with socially defined ideas about identity in a public way—and much less “intrinsic” exploration of self (e.g., time spent getting to know oneself through interior sensing and discovery). In caricature, today’s youth spend much more time figuring out what to tell others their pronouns are—or how to make a meme that will inflame those who police pronouns—and much less time walking in nature and exploring what it feels like to be in their own skin.

The problem is that the inner self is not something that can be extracted piece by piece and plastered on a social media feed. It is shy, changeable, deep, multi-faceted, and strange. Knowing oneself is a lifelong endeavour because at the core of each of us is a mystery we will never fully penetrate. This is one reason the distinction between public and private spheres has existed in most societies: because some of the purest human realities show up only in contexts that feel “private.” These parts of us are precious, tender, and essential: one cannot have a fully formed adult self without them.

Young people today are shaped by a context that all but prohibits them from forming this kind of inner self. It would be hard to create a more damaging environment if one tried. Can you think of a more effective strategy than giving giant corporations major financial incentives, nearly unlimited funds, and the world’s most brilliant minds to addict underdeveloped, socially motivated brains to a product that directs their attention outward?

Research suggests that teens and young adults create more and more sophisticated “presented selves” that may or may not mirror their “authentic selves.” Perhaps because of the developmental requirement of individuation, people at this age are acutely aware of any gap between the authentic self and the presented self—and the social media–driven social world that today’s youth grow up in causes that gap to become larger and larger.

At the core of this problem is confusion over this question: What is an identity? Human societies have generally provided for identity development simply via daily life structures, but today’s society does not equip youth even to understand what a robust identity is, let alone practice it. Instead of providing experiences that can be containers for nuance and complex inner realities, today’s developmental environment provides words and labels and flat categories.

Irwin asserts that “we have a different relationship to personality traits than you [older generations] do.” There has been a proliferation of attribute words that young people “identify as”—ranging from asexual to BIPOC to neurospicy. This is ultimately an attempt to capture all that is human in categories that can be named, chosen, pinned down, and affirmed.

TLDR (more slang): the tools young people have at hand to create an identity are different from those of prior generations, and they are not adequate. The severe increase in mental health problems today’s youth exhibit is a natural consequence of this developmental environment. First, the authentic self is a vexing thing; adults at every age struggle to deal with its warts and vicissitudes, and young people receive essentially no tools to deal with it. Second, enlargement of the gap between authentic and presented self is psychologically uncomfortable at any level, and it ultimately pre-empts the experience of unconditional love. Presented selves are by definition curated: they are designed to accommodate the conditions individuals perceive are required for acceptance—for example, I post only pictures of myself that I think others will find pretty. But the most important thing for a young psyche to feel is unconditional acceptance, and paradoxically, the more I hear positive reactions only to my presented self, the more certain I become that my authentic self would be rejected. And so I am more careful to ensure that no one ever sees the ugly “real” me—and my sensation of intrinsic worthlessness grows and grows.

Thanks to this extrinsic-centric identity formation, young people struggle to navigate their own experience, and they struggle even more to navigate the world.

What Institutions Are For

In The Ethics of Authenticity, Charles Taylor deftly articulates the role institutions play as crucial mediating structures that help individuals, especially the young, navigate the relationship between personal meaning and collective life. Their role, however, goes far beyond practical function: institutions shape how we understand ourselves and our place in the world by embodying and transmitting “social imaginaries”—the shared frameworks of meaning that undergird an individual’s understanding of their relationships, their purpose, and their own soul.

In Taylor’s thinking, young people are not wrong when they reach toward institutions as they seek to connect to something greater than themselves. Institutions embody an epistemology, an ontology, and a narrative about what constitutes a meaningful life. This is especially vital for the young, who suffer particularly severely from what Taylor calls the “malaise of modernity”—a sense of flatness, meaninglessness, and disconnection from larger purposes beyond individual self-fulfillment. Young people are fired by the moral ambition described of Dorothea in George Eliot’s Middlemarch: they still have stars in their eyes, a sense of their own potency, and a vision of the good as yet unpoisoned by the world’s bitter truths. The “disenchanted” world Taylor observes in secular reality leaves this moral ambition no place to go, so it manifests itself in zealous political energy or fizzles into video game–distracted ennui.

Institutions are the entities that teach people how to take the raw materials of their souls and make of them a life worth living.

Institutions are the structures that teach people how to bring that moral ambition into contact with the world in a way that is productive, sustainable, resilient, and ultimately fulfilling. In simple terms, they are the entities that teach people how to take the raw materials of their souls and make of them a life worth living.

Without them, as Taylor points out, young people are at risk of falling into what he terms “the culture of authenticity” gone wrong: an excessive focus on individual self-expression that lacks grounding in shared goods or transcendent experiences. Anyone who has spent even a modicum of time on TikTok can see this culture running rampant.

Hannah Arendt’s understanding of institutions articulated in The Human Condition provides a helpful complement to Taylor’s. She views institutions as constituting “the world”—a shared, durable space between people that outlasts individual lives and provides the stage for human action and speech. To Arendt, institutions are what give the world substance beyond the fleeting realm of subjectivity. The distinction between public and private is thus essential to their function: institutions are the public, shared knowings that are more concrete and have been tested by the process of coming to (at least partial) consensus among diverse, subjective minds. They are necessary because they create the possibility of real human community. Without them, all that remains is a facsimile.

Arendt was already worried in her time by what she called “the rise of the social,” a sense that modern society was becoming dominated by “social” concerns at the expense of genuine political life. She would be horrified by the world Gen Z has walked through, one marked by a dangerous trifecta: worldlessness, the loss of plurality, and the collapse of the public-private distinction. Here is how this trifecta works itself out: zoomers’ primary social experiences happen in spaces that aren’t durable or shared in the way Arendt meant. Platform algorithms create individualized environments that feel social but are actually private, so they are not part of a genuinely shared world. This feeds into the lack of plurality. Real plurality, for Arendt, requires people to appear before others as distinct individuals. Social media platforms tend toward conformity and performative identity rather than genuine plurality. And in the case of the public-private distinction, young people are developing in an environment where private thoughts and feelings are constantly made public on social media, while “public” discourse is increasingly privatized and individualized by fragmented media streams that micro-target each “discourse” consumer.

This last point is perhaps the most key. As we have seen, Gen Z has grown up in an environment with a fundamentally dysfunctional arrangement of extrinsic and intrinsic identity formation. The performed self has been overemphasized; the authentic self nearly forgotten. Existence is not palpably separate from performance. Without a distinct private sphere, there is no distinct public sphere, which is where institutions would live. So zoomers engage in a way that blurs interior self and external representation, corrupting all the elements involved.

Public life feels inextricable from private reality, which makes them hypersensitive to whether the external representation of anything they’re part of fits their self-concept. Additionally, without the grounding in the messiness of internal complexity, public expressions become shallow and shrill, demanding with progressively louder megaphones that the world conform to an asserted order of justice that has no room for human variation. The quality of public and especially political life deteriorates.

Private life is de-emphasized and partially erased. But, of course, it cannot be eradicated, so it festers instead, rumbling in the deep, periodically casting forth uncontrollable fears and hopes and sensations that cannot possibly be ignored or rendered rational. And zoomers have only thin, pop-therapeutic concepts to try to make them tolerable.

Perhaps worst of all, the relationship between public and private life is warped beyond recognition, which amounts to the breakdown of relationship between the individual and society. The young person longs to be part of something and to offer herself for something higher, and society craves young energy and fresh dreams. But as things are presently constructed, the two can never meet.

Out of the Morass

So how should institutions, inherently built as paths to cross this chasm, respond? What should their leaders do?

The task is daunting. Essentially, we must remediate the blurring of the performed and the authentic, the extrinsic and the intrinsic self, and simultaneously guide the rising generation through the normal lessons of meeting the world as it is rather than as it should be. If we can do this, we will re-ground public life, teach private life, and repair the relationship between individuals and the societies in which they live.

One of the virtues of youth is its allergy to wrong. Young people are not yet desensitized to the ubiquitous presence of sin, injustice, agony, and evil, in all their blatant and implicit forms.

This is at core a gift to the world, and it is what gives the youth of any era a prophetic personality. They insist on the good, the true, and the beautiful in utter defiance of what they see around them. When the Lord makes all things new, he will remake them in a way that the young would not only delight in but expect with confident trust.

In the meantime we need help to navigate the wrong all around us. Institutions are mediating structures with this fundamental purpose. The private sphere is essential because it can be a safe home for the holy. It is a deep internal space that can hold both purity and nuance, dreams and individual experiential truths. Institutions are bastions of the sensible and by their nature are accommodations between competing interests; sometimes they are testy but stable resolutions of deep tensions (or arrangements that are good enough for now). We need this separation for both to be able to retain their core nature: one a container for the pure and one for negotiating the realistic.

Institutions have a few core truths that young people desperately need to learn. There is a fallacy central to Gen Z thought: that compromise is betrayal. But compromise is the only way to have relationship, whether between a husband and wife or between a young person and society. Young people do not want to compromise their values for the sake of the world’s “reality,” but in refusing to do so, they ensure that their values will never become the world’s reality.

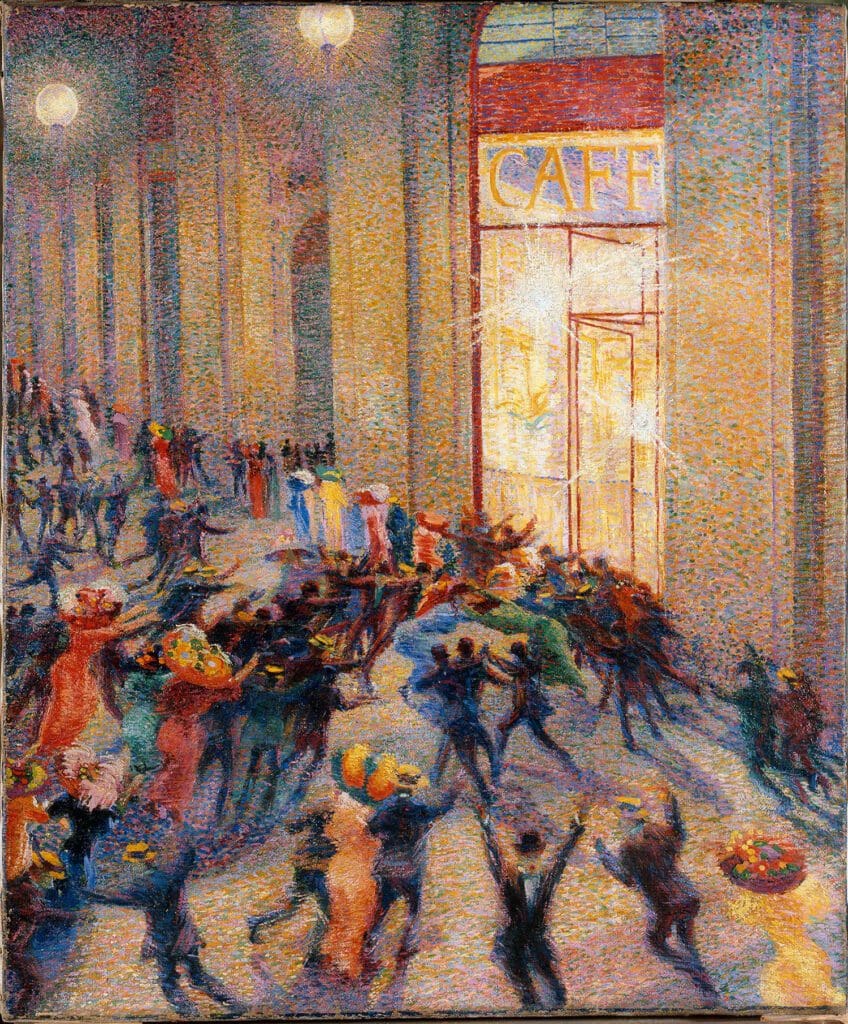

It is easy to look at inspiring pictures of the March on Washington and feel your heart skip a beat. Images of the saints, whether sacred or secular, have always been moving in their purity. But the beloved community will never be created via marches alone, much less by just the right hashtag. It will be created via the slow negotiation of one group’s interests in tension with another’s. The achievement we call the civil rights movement was a careful cultivation of tolerable alliances between bitterly divided factions much more than it was of march-planning. The work that went into forging and maintaining those alliances dwarfs the amount of time and effort that went into planning the March on Washington by a hundredfold.

And this is why we need institutions: they are the arrangements we’ve already come to, the protocols we’ve found to make things work well enough for now. They represent the problems we’ve already solved, or at least have mitigated enough that the real work can move forward. They enable us to stop talking about whether poor whites have a place in the civil rights movement and get to the business of marching.

Better yet, in Taylor’s terms, institutions are the hermeneutic structures we can use to make of ourselves something truly worth being. They offer us the handholds that empower us to climb out of simple understandings and desires for the good into a form where we can actually create the good. Institutions gift us with the best of our ancestors’ understanding of who and what we are, and how we can pour our spirits out into the world with maximal effect. They are the road map toward the beloved community, in boring, grey, stubby little packages.

One of the only words that speaks to every group—whether black or white, liberal or conservative, spiritual or secular or religious or “none”—is “dignity.” Young people want to make the world just, make it dignify everyone. What they don’t understand, through no fault of their own, is that dignity isn’t usually dramatic. Yes, sometimes people are struck by the vision of a Rosa Parks and her inalienably dignified spirit. But more often dignity is shown in the way someone lets you go in front of them in the airport line, or in the appreciative and respectful way they talk about someone they think believes something totally wrong. Or when your friend hangs out with you when you’re feeling bad, even though he doesn’t really understand why. Or when the insurance agent on the other end of the line can’t actually fix your problem, but she listens to you all the way through, and you feel heard.

It’s the slow, daily, deontological honouring of dignity in a thousand small moments that ultimately adds up to the relationships that can transform a life or a nation.

Dignity seems easy when you’re looking at slogans, but life requires dignity in the tense, difficult moments. Most people can accept all kinds of hardship if they feel they are treated with dignity. People can be fired from jobs they love; spouses can leave them behind—but how this is done, with what measure of dignity the act is conducted, will stay with them for the rest of their lives. The same goes for communities and for societies. This is the kind of dignity institutions teach and express: the protocols that recognize the respect each person or group deserves to receive, the needs they deserve to have met. It’s the slow, daily, deontological honouring of dignity in a thousand small moments that ultimately adds up to the relationships that can transform a life or a nation.

This kind of dignity is, frankly, hard to learn and harder still to act out. It requires constancy, and each instance is small. The youthful prophetic spirit is drawn to big, dramatic action that can (we imagine) remake the world in one fell swoop. But for the most part, that’s not how things change. Even the pinnacle achievements named in history books were the culmination of countless small labours; the Civil Rights Act of 1968 was built on hundreds of thousands of semi-successful pedestrian efforts over dozens of years.

Institutions Gen Z Style

In a way, members of Gen Z need institutions even more than the usual crop of up-and-comers, because their ability to run into the real world without cracking is weaker than that of prior generations. They are already encountering these challenges, and the results are not good. The prophetic spirit is known as prophetic partly because it is alien to the world. It isn’t fun to be a prophet. Today’s young people need to learn how to hold the purity of their dreams in a way that is resilient to the avalanche of failure and sin the world will pour on them. Like all of us, zoomers need to learn complex ways to engage their moral yearnings. They need the practices of lament, grief, prayer, and ultimate hope to withstand the slings and arrows the world will sink into their hearts. Right now, there is an open question: When hopeful members of Gen Z encounter the world, will they be desensitized and crushed, or can they take their lessons and transmute them into wisdom and strength?

They will need institutions if they hope to achieve the latter. The sad truth is that when youthful dreams meet the world’s patterns, the world usually wins. Institutions offer the only reasonable path to victory, and they must show young people that this is true.

To achieve this, we need an unusually gifted generation of institutional leadership. It is difficult to lead institutions these days, not least because what they must achieve is reform, and they’re working with revolutionaries. But it’s not impossible. Some of their adaptations should be Gen Z–specific: collective narratives, for instance, need to be simpler, reflecting the frames Gen Z is accustomed to. Narratives now tend to be flatter and less nuanced, shaped by decentralized, egalitarian, social media–driven movements—think BLM or MeToo—that operate by a logic nearly identical to individual morality. This logic sidesteps the sacrifices and tensions inherent in groups and institutions that endure over time. At the same time, new institutional leaders must be humble: zoomers do understand many social dynamics more deeply than anyone else alive today, having come of age within the social and technological architecture that is currently driving everything.

One thing we have on our side is that the forms of engagement young people are demanding will also, if conducted wisely, revitalize our institutions. They will force our structures out of some of the calcification that caused the mass loss of faith in them to begin with. It will be a process of creative destruction—make no mistake, this will not be smooth—but it’s ultimately in the direction of life.

Let’s take churches and other religious institutions as one example. Churches are in a unique position to teach interiority, as they explicitly deal with the unseen. Christian activity in the world can—in fact, should—be an expression of the desire for a world much better than the one we see. Religious institutions are in an ideal position to add the depth needed to ground shrill activist sentiments, and at the same time they must teach the humility needed to engage the real world—their credibility depends on it. Most importantly, they must teach that the gospel is deeper and bigger and more radical than any political movement. Religious visions are the only ones that are adequate to the intensity of Gen Z’s moral ambition.

If churches can demonstrate both—acting in the world and developing interior life—and illustrate the relationship of deep intertwining between the two, then they can provide a foundational service to young minds and hearts, which will then offer vibrancy to the entire community. It’s not easy to demonstrate this in a way that will compel Gen Z, though. As noted, they are suspicious and skittish. They will come only for the real thing. We must imitate Jesus if we hope to compel their trust. And if we can do that, we will win powerful passion and devotion.

Perhaps this could push the American church toward the style of Christianity practiced by Jimmy Dorrell’s Church Under the Bridge in Waco, Texas. Dorrell is a pastor who began holding church services under a local highway overpass, because that’s where the people society had left behind were. Rather than wondering why they didn’t come to church, he took church to them. That’s inspiring.

Very similar things could be said of universities and their relationship to Gen Z. They have a mandate to teach a credible, grounded interiority and how it should manifest itself in the public sphere. And they have a structure of mentorship that, done properly, should cultivate effective relationship between the two. Ultimately, what leaders of any institution must do in this era is not altogether different from what leading young people has always meant. We need leaders who can speak to the moral passion these folks bring, meet them there, and then guide them, walking side by side, toward the way this passion must meet reality. They must model the messiness and struggle and, most crucially, the integrity in that. And in doing so they must model maturation: the practiced balancing of cherished dreams and humility before the world’s challenges, holding on to a form of ultimate hope that is resilient in the face of even the worst obstacles.

If institutional leaders rise to the challenge, members of Gen Z will learn that they do not have to choose between their prophetic yearnings and the strictures of the world. If they work with institutions and allow themselves to be formed, they can learn a way of moving in the world that brings the one into the other, shifts us closer to the beloved community, and refines us, person by person, along the way.

Institutions promise this to young people, and Gen Z aches to come through the door and walk this path. May we steer our institutions with the wisdom, creativity, and hope that will enable us to deliver on this promise.