L

Late in 2022, a researcher at Cambridge University preached a sermon at an Evensong service in Trinity College Chapel that reportedly left some congregants in tears. Normally a homilist might take such a response as a feather in her cap, but in this case the tears were apparently born of outrage rather than gratitude or devotion. The preacher, Joshua Heath, a doctoral supervisee of the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, began his sermon with a prayer and then offered a meditation on several pieces of visual art in which the crucified Jesus is depicted as (how best to summarize it?) ambiguously gendered.

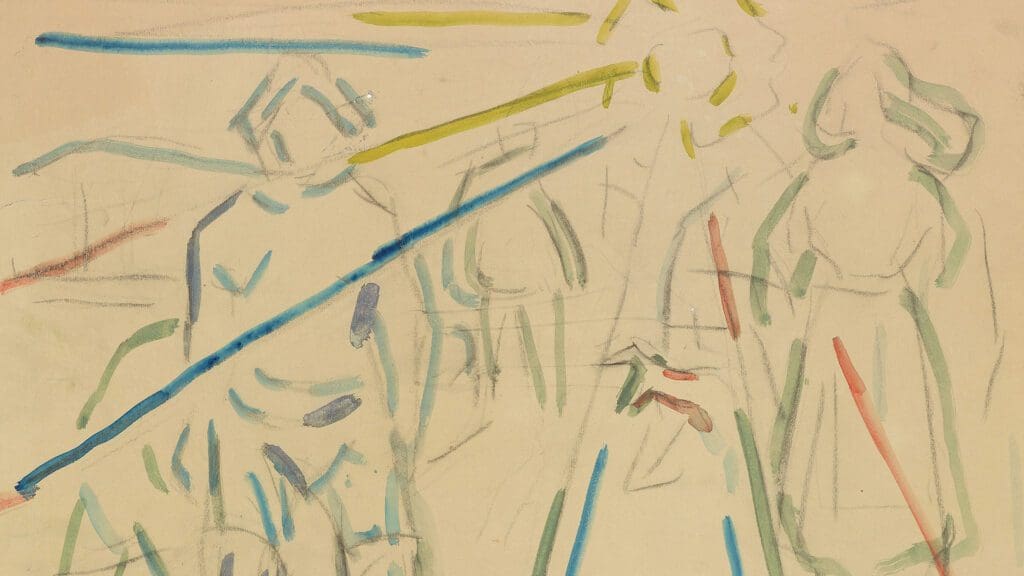

His chief example was from the French artist Henri Maccheroni. From 1985 to 2002, Maccheroni worked on a series of engravings of a male torso. The works are abstract, but the inspiration seems clear enough. In one piece, virtually the whole canvas is taken up by a ribcage whose diagonal slashes could be read as bone protuberances or marks of flagellation; darker smudges suggest open wounds; shadowed armpits stretch and yawn, as if the subject’s arms are splayed crosswise; and—most prominently and provocatively, forming the centrepiece—an inverted triangle, vulva-like, angles up to meet horizontal shadows that mark the beginning of pectoral muscles. Some of these engravings were published along with poetic texts in a 1993 book titled, with a deliberate lowercase, christs. They’re works about Jesus, but, they suggest, Jesus’s body is also ours—male as well as female.

In his homily, Heath stressed the long Christian pedigree Maccheroni drew from in crafting these works. Representing Christ “in ways that make matters of sex, gender, and sexuality unavoidable is an important part of the inheritance of the Western Christian tradition,” Heath said. “Maccheroni’s images . . . reactivate that tradition, proving in some ways more in keeping with the historic spirit of Christian devotion than our [modern] prudishness about matters bodily.”

Heath refers here to the tradition stretching from Julian of Norwich and Catherine of Siena to the Anima Christi prayer attributed to Ignatius of Loyola, in which Jesus is portrayed with motherly imagery, not just fraternal (as he is in the New Testament), and the faithful pray to fold themselves into the incision in his side, the gap opened by the soldier’s spear, from which blood and water flowed as they do in childbirth. The thirteenth-century abbot Aelred of Rievaulx called the wound a “hole in the wall of his body, in which, like a dove, you may hide while you kiss” his scars one by one. Multivalent, as theologian Graham Ward has said, Jesus’s pierced side is “both a lactating breast and a womb from which the Church” is born. Here matters of sex, gender, and sexuality aren’t merely unavoidable; they’re intertwined and entangled in sometimes bewildering and beguiling ambiguity.

From a historical vantage point, neither Maccheroni’s modern etchings nor Heath’s homiletic riff on them should be understood as a shocking new departure. It was the conclusion Heath drew in the end that set off the culture-war powder keg: “If the body of Christ is, as these works suggest, the body of all bodies, then his body is also the trans body, and [the] word [of trans bodies] is his word.”

That’s the point when the congregants’ tears of confusion and dismay started flowing.

As I write, it is Pride month in 2023, the annual celebration of the dignity, achievements, and rights of LGBTQ+ communities. Even small, heartland-of-America towns like the one I live in are hosting parades and outdoor parties. The White House is currently flying the Progress Pride Flag, a modified traditional rainbow flag meant to signal transgender and nonbinary advocacy alongside lesbian, gay, and bisexual affirmation. Meanwhile, the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest Protestant denomination in the United States, just passed a resolution to “condemn and oppose so-called ‘gender-affirming care’ and all forms of ‘gender transition’ interventions” as “direct assault[s] on God’s created order and . . . futile quest[s] to change sex (an impossibility).” Across the Atlantic, Britain’s National Health Service has just announced a curtailment of puberty-suppressing drugs for children in clinical trials, citing lack of evidence of effectiveness. The Western world, at least, seems poised to erupt over gender identities and expressions.

What difference does Jesus make? Does his life—a wholly divine life, lived fully in male Jewish flesh, for the sake of women, men, eunuchs, the entire disparate lot of humanity—help us navigate the troubled waters of gender?

For Christians, Joshua Heath’s Cambridge sermon asks the most important question amid this maelstrom: What difference does Jesus make? Does his life—a wholly divine life, lived fully in male Jewish flesh, for the sake of women, men, eunuchs, the entire disparate lot of humanity—help us navigate the troubled waters of gender?

Some Christians have underscored the strangeness of Jesus’s sexed, gendered life. Put in the simplest terms, as Amy Peeler does in her recent book, Women and the Gender of God, the Gospels portray Jesus as “a male-embodied Savior with female-provided flesh.” From the beginning of his life, Jesus’s unusual paternity begins to scramble our categories of “normal.” Beyond the canonical depictions, other clerics, visionaries, and artists have made Jesus’s gender atypicality a central theme of their work, sometimes to the point of scandal. On Maundy Thursday in 1984, the English sculptor Edwina Sandys, a granddaughter of Winston Churchill, had a 250-pound bronze statue of a crucified female—titled Christa—displayed at the high altar in the Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan. After hate mail began to pour in (the bishop himself declared the piece “theologically and historically indefensible”), the sculpture was removed but not before the point had been seared in the cathedral’s consciousness: Jesus might be depicted with breasts, wide hips, and no beard, a victim and saviour for whom female flesh was no more distant than male.

Before I knew the word “gender,” I became aware of the tremours the gendered body of Jesus can set humming in other bodies. I grew up in a fervently Christian household. We were fundamentalists, but we weren’t iconoclastic Presbyterians: Images of Jesus pervaded my childhood. Our shelves (and floors) were covered with Christian books, most of them filled with pictures, and my earliest memories are crammed with visions of the stripped, contorted body of Jesus on the cross. I gazed at reproductions of the crucifixion for hours on end in the days before the internet, leafing through black-and-white images in encyclopedias, religious almanacs, children’s Bibles, and anywhere else I could find them, fascinated by the audacity with which the artists rendered minutely the details of the male form: musculature, hair (mostly its absence), nipples. There were, among others, the curvaceous Christ of Rubens, in the process of being hoisted upright on the crossbeams; the spent, pallid Christ of Velázquez, lank hair hiding half his face; the pious Christ of Bonnat, veins and ribs popping, fingers curled like arthritic talons around the nails in his palms. I pored over these depictions, my face sometimes flushed with awkward self-awareness, torn between the chaste devotion I supposed they were meant to evoke in me and the more carnal curiosity they inevitably churned up.

When, much later, I encountered the infamous judgment of evangelical celebrity pastor Mark Driscoll—“I cannot worship the hippie, diaper, halo Christ because I cannot worship a guy I can beat up”—I was already primed to understand the sentiment. I had seen firsthand how literary, even scriptural, and artistic depictions of the crucified Jesus, with their evocations of gender trouble, had the power to summon devout if conflicted attraction, confused revulsion, or some inchoate mixture of the two.

Jesus is decidedly not female—and certainly not trans or genderfluid—in this understanding, but he hasn’t stopped serving as a screen for anxious projections of our contemporary gender troubles.

One Protestant pastor, Dale Partridge, author of a book titled The Manliness of Christ, recently scorned what he calls “the anemic and soft-smiled Roman Catholic paintings where Jesus looks like He’s just put on a fresh coat of blush and tweezed His eyebrows.” Rather, “God, at a physiological level, sent His Son Jesus into the world with a male, testosterone-producing body that equipped Him with the masculine attributes required to fulfill His physical duties as Messiah. He was not toxic or effeminate. He was wonderfully and perfectly masculine.”

Jesus is decidedly not female—and certainly not trans or genderfluid—in this understanding, but he hasn’t stopped serving as a screen for anxious projections of our contemporary gender troubles.

The language of “sex” and “gender,” not to mention any neatly corresponding concepts, were of course entirely absent from the world of the writers of the New Testament. Even so, it’s possible, I think, to trace a line from features of the Gospels’ rendering of Jesus’s character and life to our modern worries and questions. Luke mentions Jesus’s circumcision when he was eight days old (Luke 2:21; cf. Leviticus 12:3), gesturing toward his sexed body: Jesus was a Jewish male with, presumably, intact genitalia (see Leviticus 21:16–24). At the same time, as the New Testament scholar Brittany Wilson has shown in her book Unmanly Men: Refigurations of Masculinity in Luke-Acts, Jesus’s expression of his masculinity—his “gender performance”—in the remainder of Luke’s Gospel fails to conform to the elite Greco-Roman ideals of the first century. According to Wilson, it was broadly agreed that elite men should not act like women or resemble too closely those “non-men” who did. Men should exhibit control over their bodies, maintaining composure and self-restraint. And, crucially, men should wield power.

By all three criteria, Jesus failed. Unlike most men of his circles, he remained unmarried, foregoing or sublimating sexual potency. He left home and opted for a kind of nomadic existence: “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head” (Matthew 8:20). Luke’s account of Jesus’s passion, in chapters 22 and 23 of his Gospel, highlights his progressive loss of bodily self-mastery: he sweats in agonized prayer before his arrest, as if secreting blood; he is manhandled; he is blindfolded and battered; he is mockingly costumed; and he is flogged. And although Luke has him die with last words of apparent serenity and calm (“Father, into your hands I commend my spirit”), Wilson argues that this nod to the Greco-Roman tradition of a noble martyr’s death still places the accent on his powerlessness, his being “unmanned.” Jesus is, in Luke’s portrayal, “fully God and fully ‘man-nonman’”: divinely omnipotent, with what Wilson calls “powerless power,” as an emasculated, criminalized outcast.

Outside the Gospels’ narratives of Jesus’s ministry, trial, and death, the picture becomes even more complicated. In the first portions of the New Testament to be written, the letters of Paul, we learn almost nothing about Jesus’s life and character prior to his death on a cross. Instead, Paul focuses relentlessly on the shame of Jesus’s death. For Paul, Jesus is defined by his self-giving, and the victory he thereby achieved is thus a highly ironic one. Jesus “emptied himself, taking the form of a slave . . . and became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross” (Philippians 2:7–8). As a result, God has raised him from the dead in the power of the Holy Spirit. In order to encounter Jesus now, one must look for him in the loaf of bread and the cup of wine at the eucharistic table (the emblems and tokens of his death), and in the community gathered around the table who share those elements (whose lives of humility are meant to mimic his). If you want to “get at” the gendered Jesus, in other words, you have to look for his body in what isn’t simply and biologically male: in food and drink and in what Ward calls “the multi-gendered body of the Church,” the family of women and men who are enlivened and impelled by his Spirit.

In what was probably the last book of the New Testament canon to be written, the Apocalypse of John, Jesus appears at first glance almost cartoonishly masculine. He rides a stallion at the head of an army, eyes blazing, ready to “wage war”: “From his mouth comes a sharp sword with which to strike down the nations, and he will rule them with a scepter of iron; he will tread the winepress of the fury of the wrath of God the Almighty.” It may seem hard to gainsay what Driscoll says about this passage: “Jesus is a prize-fighter with a tattoo down His leg, a sword in His hand and the commitment to make someone bleed.” But also here, in this most pugilistic of passages, the imagery turns out to be less than straightforward. As the Anglican ethicist Oliver O’Donovan has pointed out, there’s “something highly paradoxical about the picture of the Prince of Martyrs constituting himself the head of an army of conquest. It is an image which negates itself, canceling, rather than confirming, the significance of the . . . categories on which it draws.” Several details give the game away: Jesus’s robe is dipped in blood before the war commences (implying it is his own blood, given freely), the sword he wields he holds in his mouth (it is the “sword” of his speech, his summons to repentance and forgiveness, not a literal blade), and the name he bears—“King of kings and Lord of lords”—suggests that while he may wield the trappings of earthly warmongers, his authority ultimately transcends those outward markers, willing and securing the eternal good of his enemies, rather than their destruction.

Rogers Brubaker, a professor of sociology at UCLA, has proposed a template for thinking about different kinds of self-understanding among transgender persons. In the first instance, there is the “trans of migration,” a movement from one clearly defined category to another (male to female, or female to male). This is perhaps the most popular way to understand trans experiences by those who are content to identify with the sex they were assigned at birth, as well as among many trans people themselves: Transgender persons are “born in the wrong body.” This is also the understanding of trans experience that some of the congregants who heard Joshua Heath’s Cambridge homily objected to. “I am contemptuous of the idea that by cutting a hole in a man, through which he can be penetrated, he can become a woman,” one hearer wrote to the chapel Dean. “I am especially contemptuous of such imagery when it is applied to our Lord, from the pulpit, at Evensong.”

Then, says Brubaker, there is the “trans of between,” the experience of skirting or missing the dominant binary choices, of finding one’s gender identity somehow out of sync with prevailing norms. Last, there is what Brubaker terms the “trans of beyond,” the quest to discover or explore a gender identity on the frontiers of what is currently thinkable: hence terms such as “genderqueer” or “genderfluid.” Although these categories may be less familiar in mainstream discussions, they underscore the inadequacy of the born-in-the-wrong-body framework for capturing the nuances and complexities of many experiences of gender transition.

Keeping in mind the constant danger of anachronism, might we at least wonder whether the Jesus of the New Testament could be newly approached within this framework? Or, just as importantly, might our contemporary response to him also be freshly understood by, as Brubaker recommends, “thinking with” trans experiences?

On the one hand, the sexuate body of Jesus doesn’t seem especially ambiguous in the New Testament, especially the Gospels: He is a man, whose penis is circumcised, addressed and spoken about with male pronouns. Nor does he shy away from identifying with Israel’s greatest masculine warrior king, David, whose heir he claims, directly and indirectly, to be. Yet if, as Scott Bader-Saye has put it, gender is “a complex relationship between one’s sense of self, one’s bodily sex traits, one’s experience of the attention of others, one’s location in the gendered social system, and one’s understanding of human purpose,” then the picture becomes murkier. Jesus’s sex traits may not be uncertain, but the way others perceive him suggests that he destabilizes cultural norms of what it means to be an upstanding man in his first-century world. His place in his gendered society becomes increasingly fraught and confused, the closer he moves toward his humiliating, emasculating execution. And as his ultimate aim—to redefine a militarized office of kingship by an act of radical self-abnegation—becomes increasingly clear, his place in the hierarchy of “manly men” is forfeited, so that even his closest allies abandon him to his ignoble fate.

All of which raises the question: what does this mean for those of us who wish to follow and worship him as God?

The central confession of the Christian faith is that Jesus of Nazareth, uniquely one with the eternal Source of all life, is at the same time completely and unassailably human. As we say in the creed, the Son of God “for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man.” The point here is the total solidarity of Jesus with the entirety of the human family, without exception. His maleness is secondary to his humanity: He is no less capable of identifying with and saving women than he is men, and vice versa.

At the same time, the particular human life assumed by the Son was male, though Christian theologians in every generation have debated what significance they ought to assign to this fact. Augustine, taking male priority for granted, assumes Jesus “had to be that”: “he came as a man, to show his preference for the male sex, and he was born of a woman, to give comfort to the female sex,” which might otherwise despair of its inclusion in the circle of redemption. Thomas Aquinas, likewise, argues that because of male headship in marriage, the Son had to be male because he came to be the head of the church, his bride. Many others from across the ecclesial spectrum have followed suit.

The problem with arguments like this, however, is that they too quickly elide the distinction between gender as we know it now and gender as divinely envisioned and intended. Augustine and Aquinas, never mind their lesser heirs, do not, I think, sufficiently interrogate how far their conceptions of male dominance and authority owe to the world’s fallenness rather than anything delivered by divine revelation. It seems that empirical observation of the relations between the sexes bears more weight in their arguments than it should, leaving little room to say about the present order that it’s not the way it’s supposed to be.

But Christian theology should pay equal regard to two poles, not just one. Because we affirm that God is the maker of all things, Christians ought to look for ways to celebrate and honour the givenness of creation and its essential goodness. Sexed bodies, gendered selves—as Augustine knew better than any early church father—are the stuff of God’s design and will somehow be reclaimed and restored in God’s future, rather than set aside. That future restoration, though, is the second, crucial pole in a Christian understanding of gender, which presses us to say not only that gender is good and will be preserved but also that its present instantiations differ significantly from how they will appear in their eschatologically redeemed form. In the second of C.S. Lewis’s Space Trilogy novels, Perelandra, the protagonist, Ransom, meets the king and queen of Venus, who are untainted by original sin as earth dwellers are, and exclaims, “I have never before seen a man or a woman. I have lived all my life among shadows and broken images.” Maleness and femaleness, masculinity and femininity, as we citizens of a fallen world know them now, are only pale reflections of what they were meant to be—and what they ultimately will be.

Theologian Sarah Coakley, who has probably done as much as anyone on the contemporary scene to press home this latter point, has argued that Christian theology can go a long way in tandem with secular gender theory in critiquing “cultural presumptions about gender that are often unconsciously and unthinkingly replicated” to the detriment of persons who struggle to discern where or how they fit in the so-called gender binary. Whereas gender theory recommends a self-styled parodic resistance to that binary, however, Coakley turns to specifically “theological concepts of creation, fall and redemption which place the performances of gender in a spectrum of existential possibilities between despair and hope.”

We have not (yet) seen what true masculinity and femininity look like. At present we live among shadows and broken images. But one day, we believe, the shadows will give way. And even now we may begin to take some halting steps toward the Light who will dispel them.