I

In 1967, at the age of forty-four, John Senior transferred to the University of Kansas. He came there from the University of Wyoming, where he had been a member of the English faculty. At his new home he met Frank Nelick, who had been teaching there in the English Department for sixteen years, and Dennis Quinn, who had been in that department for eleven. These two had known each other even before their time at KU and were already collaborating in their teaching. Nelick and Quinn immediately hit it off with the newcomer. The three professors were in deep agreement concerning the fundamentals of Western civilization, they all loved poetry, and they believed that in a university setting teaching should have primacy over research and publication. Most especially, all three saw the need to form students’ imaginations and emotions as well as their intellects. They recognized the importance of forming underclassmen instead of leaving them to graduate assistants.

The professors decided to teach a class together for freshmen and sophomores. More than a class, a program. Given their communion of ideas, they quickly drew up its essential structure and direction. It would be integrated—that is, it would group together the disparate strands of the freshman-sophomore liberal arts core curriculum into one two-year program so that the different subjects could be seen as organic parts of a whole. It would be a humanities class—that is, the goal would not be to transmit techniques or information but to humanize. And the professors judged that the most effective means to help students in the art of being human was, as Senior explained in a paper defining the program, “to read what the greatest minds of all generations have thought about what must be done if each man’s life is to be lived with intelligence and refinement.”

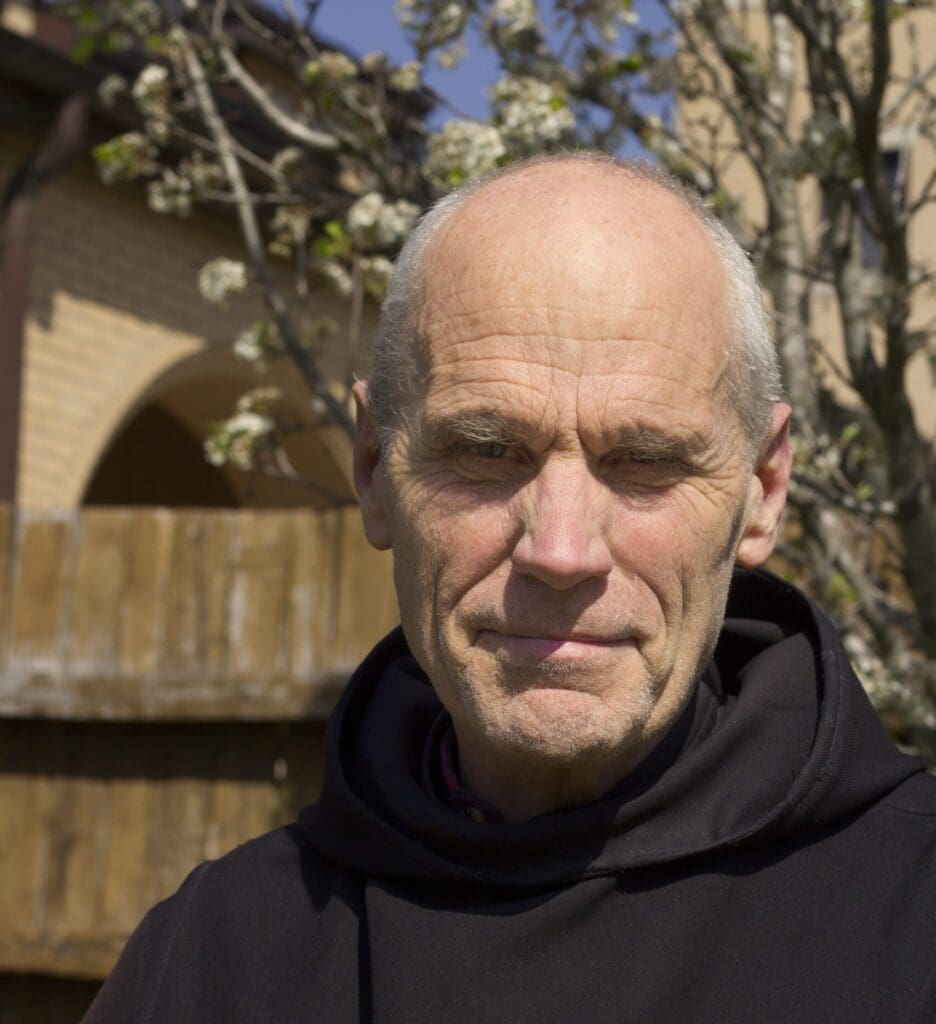

Thus was born the University of Kansas’s Pearson Integrated Humanities Program, or IHP, as it was called by those involved. In the short time of its existence in the 1970s, at a secular university, during a time characterized by drugs, rebellion, and rock and roll, hundreds of young adults were turned instead to tradition, to the great books, and to Western civilization. Many, in the end, turned to God and to Christ. The three professors jokingly called the program an “experiment in tradition”—as if traditional education were an unsure, untried novelty!

But IHP was a sort of novelty. It was certainly new for the students. And the professors found ways to renew tradition that had wide and sweeping effects beyond the classroom and the university campus.

Forty years after the program’s end, its influence endures and continues to grow. The institution from which I write, Our Lady of Clear Creek Abbey, in the foothills of the Ozarks in eastern Oklahoma, in some ways owes its existence to the program. Wyoming Catholic College was founded largely on IHP’s principles. Many teachers and even some university departments have made attempts to imitate it. Numerous schools in the fast-growing classical school movement are directly inspired by it. Two boys’ schools, St. Gregory the Great Academy and St. Martin’s Academy, are built on Senior’s principles. In fact, any place you can find a Catholic great books program, it is not uncommon to find a “Pearson family” (or two or three) near the centre of it. John Senior’s books grow in popularity and have been translated into Spanish, Portuguese, and French. And several academic studies of Senior and the program, at both the master’s and doctoral level, are completed or currently underway.

We are made for the stars but rooted in the soil. We are made to seek spiritual realities, but we must use this world, this visible creation, to do so.

A line from Senior’s book The Restoration of Christian Culture goes to the core of IHP’s perspective: “There is something destructive—destructive of the human itself—in cutting us off from the earth from whence we come, and the stars, the angels, and God himself to whom we go.” We are made for the stars but rooted in the soil. We are made to seek spiritual realities, but we must use this world, this visible creation, to do so. This is the path God gives us to rise to him. It was also the characteristic principle of IHP.

In what follows I mainly quote Senior since he wrote much more than the other two professors, but what he says represents the three professors’ educational views and the methods they used to apply them. The situation they faced is not all that dissimilar from those that professors and their students face today. It has been pushed further to the extreme, but it has the same underlying currents. Perhaps, then, we may take inspiration from their example.

Teaching Discovery

The general features of the Integrated Humanities Program resemble those of the great books programs begun in the 1920s at the University of Chicago and which Senior had enjoyed at Columbia, and which other schools were pursuing at the time. But these programs centred mainly on philosophy. The three professors knew that their students were not ready for such studies. As Senior said concerning these programs in a letter to his mentor and friend Mark Van Doren, under whom he had studied at Columbia, “[You shouldn’t] send a young person to college without his having been to [high] school. The liberal arts college begins with wonder and ends in wisdom. But the freshman has had wonder pretty much crushed out of him. It seems criminal to teach [the mathematical science] of astronomy to someone who has never looked at the stars.”

When the professors had taught philosophy directly in their classes, there was little echo in their students’ souls. They soon realized that this lack of response came not simply from the fact that their students had never studied logic or some other preparatory study. The problem was not only ideology, not only bad ideas that hindered their receptivity to what the professors wanted to convey. More fundamentally, the students lacked the preparation of healthy outdoor experience, and of loving familiarity with good literature and poetry. Beauty, the professors found, opened their students’ minds and hearts, making them capable of receiving truth.

Aristotle and St. Thomas teach that the human person, as a union of body and soul, lives an integrated life in which the intellect and will rely on the senses, the imagination, and emotions. The professors recognized that the new generation of students was sensibly and emotionally disconnected from reality. Their technology, their whole environment, pre-internet though it was, cut them off from God’s creation, inclined them toward fantasy. Their basic correspondence to reality, to the true, good, and beautiful, had been blunted. They were not interested in real things, were restless, could not focus.

Before undertaking any high, theoretical study, these students needed to get the feel and attraction for concrete things, to relearn the spontaneous conviction of the existence and goodness of reality. As Senior writes, “No serious restitution of society can occur without a return to first principles, yes, but before principles we must return to the ordinary reality which feeds the first principles.”

Experience, Delight, and Wonder

Throughout most of human history, people walked, rode horses, hunted, worked with hand tools, sang, and read together. But in the modern era all that had changed. Quinn, Nelick, and Senior intuited there must be a deliberate effort to restore to students healthy experience and fundamental culture, to compensate for the lack in home and society. Learning is gradual, and first things must come first. This recognition led them to reflect on the first two of the traditional steps in education.

The first step is what the Greeks called gymnastic, what we would today call physical education. The traditional perspective, however, had in view not mere recreation, muscle development, or even coordination but rather a healthy experience of nature, exercise of the senses, and the training of perception so that one discovers the rich goodness of the world, feels the immediate appeal of things.

The Greeks called the second step music, which encompasses not just what we think of as music but all that belongs to the domain of the Muse—literature, stories, dance, and drama as well as song. Here one cultivates especially the imagination, memory, and emotions in order to attune them to the beautiful, the noble. Plato writes in the Republic, “Let’s begin with the acknowledgement that education is first given through Apollo and the Muses. If one has no contact with the Muses in any way, the soul becomes feeble, deaf and blind, because it is not aroused or fed, nor are its perceptions purified and quickened.” The modern educator Allan Bloom writes along the same lines: “Education is the forming of the passions as art, with the goal of harmonizing the enthusiastic part of the soul with the rational part, by providing a continuity between what the students feel and what they can and should be.”

Senior devised a formula to synthesize these first two steps, which especially brings out the central emotion to be cultivated at each level: gymnastic begins in experience and ends in delight; music and poetic education begin in delight and end in wonder. Delighting in reality, wondering at its mysteries, with a healthy imagination, a memory full of stories, songs, poems, experiences, one would be ready for life and eventually for more elevated, abstract studies.

The Primary Things of the World

“IHP was a [high] school occupying a college,” writes Senior. “We did the poetic work that was skipped.” Educational theory tended in those days to neglect the elementary levels because human separation from the natural world was rather recent, and so deficiency in that domain had not yet taken full effect. Analysis had replaced direct experience and wonder.

IHP’s fundamental orientation is echoed in its motto, which was suggested by a student: Nascantur in admiratione—“Let them be born in wonder.” As Quinn observed, “The Program should be regarded as a course for beginners, who look upon the primary things of the world, as it were for the first time.”

The professors chose readings that were poetic and gymnastic—that is, texts the students could sensibly and emotionally participate in. About a third of these were poetry and literature: for example, Homer, Virgil, and Dickens. About a third were historical but narrated in story form and usually consisted of eyewitness accounts or autobiographies: Herodotus, Caesar, Francis Parkman. The others were didactic, with some philosophy, but philosophy that was literary and imaginative, open to a poetic approach: notably Plato and Boethius.

The professors also helped the students learn how to read. On the gymnastic and musical levels, this meant direct reading, done basically to enjoy, opening oneself up to a writing’s beauty. Although, Senior clarifies, “such experience is not sufficient . . . for science and philosophy,” it is “indispensable as the cultural soil of moral, intellectual, and spiritual growth.” Experience comes before analysis. One must first be moved by a work of art and delight in its beauty. The intuitive and the emotional precede rational discussion of causes and structure.

There was then and is now little room in a university course for direct gymnastic exercise, but the professors did urge work and play closer to nature, organizing camping trips, taking walks, advocating discipline in the use of TV. For freshmen, stargazing sessions were arranged in which older students pointed out the constellations and narrated the pertinent classical Greek myths. Perhaps for the first time since childhood these young adults felt free to respond emotionally and sensibly to the stars. In awe and admiration they experienced the call of beauty and realized there is more to reality than quantity and technology.

There were other activities, both gymnastic and poetic or musical. The professors encouraged learning calligraphy and some handcrafts. Waltzes were held; there were fairs and even trips to Europe to experience more traditional cultures. A major pursuit was memorization of poetry and songs—Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Frost—with again the emphasis on enjoyment. It would be difficult to overestimate the importance of these poems and songs in nourishing the students’ link to reality, in rousing their slumbering sensibilities and emotions to the beauty and variety of nature, to friendship and fidelity, to love.

The professors recognized that the new generation of students was sensibly and emotionally disconnected from reality.

The classes themselves consisted substantially of two team-taught classes each week. All three professors were involved. Once a week smaller question-and-answer meetings were held with one or other professor, as well as a rhetoric class with assistant teachers. Taking Latin with Dr. Senior was recommended.

The main biweekly class was unique in history. It was not a lecture in the strict sense, but simply a conversation among the three teachers. Usually one of the three would read a passage from the currently assigned book, and then the three would meditate with the students on a theme that grew out of the reading. Here were three friends who enjoyed looking at beautiful things together and helping students discover them. In an interview, Senior compared the three professors to a jazz band improvising on familiar themes: “It’s as if one of us were on clarinet and another on trumpet and another on piano. One of us starts to talk, the other picks up the tune and the other one gets the beat.”

The professors preferred this spontaneous way of doing things in order to render the class more lively and provide better opportunity for the students to glimpse something beautiful, to be attracted to great truths. The students weren’t allowed to take notes. At this stage the experience itself was more important than getting clear ideas and definitions down on paper for later. They had first of all, most of all, to delight and wonder.

We students were indeed fascinated, lifted on the wings of these teachers, as silent in class as we would be at a movie or listening to beautiful music. We came out stimulated, talking with one another about our discoveries. We could not get enough of these classes. Senior, playfully pointing to the joy of such classes, said,

Schools, because learning is a self-diffusive good, pour down love and knowledge on their pupils like voluntary rain. Ever since the Fall, men have worked in the sweat of their brow and women labored in pain. But schools (Puritans be damned!) are fun. Learning for its own sake calls them forth. The yachtsman hears the wind and waves, the hunter the horn and hounds; zealous teachers and eager boys follow the buzz, as of bees in the brain, of sensitive, affective and intelligible delight.

The Ends of Education

The professors reflected in class not in a philosophical, abstract way but by telling stories and quoting literature and poetry. They presented rather than argued, awakening and cultivating in their students attention to the natural world and to human life. This style rested on the conviction that there is a correspondence between the mind and reality, that reality itself would lead the students to the truth. For them the teacher discreetly helps students in their own natural, personal activity of intellectual enlightenment, like a coach guiding the athlete, or a mother bird helping its fledgling to fly. The professors disposed the students by desire and wonder to see significance and beauty. Their task, they believed, was to assist the books in doing their work, and they accomplished that task simply by underlining points, making connections, showing how what the author spoke of was part of the students’ experience, involving the students in the text.

The professors chose the reading passage for the day’s talk in view of a fundamental theme, such as the home and the banquet in the Odyssey, the nature of duty and “the tears of things” in the Aeneid, or “the good life” in the teachings of Socrates. Yet they did not seem to have any special long-term goal in mind. Class by class, week by week, they meandered through various themes—home, friendship, justice, work—apparently going nowhere.

Despite appearance, however, in their various meditations the professors were gently leading the students toward two goals. First, by pointing out so much beauty, they were bringing students in an experiential way toward the normal trust that the real is really real, delightful, mysterious, interesting—to wonder, as the program’s motto says. Even if the students were as yet incapable of arguing successfully in a debate, nothing could eliminate what they had seen and tasted—the splendour of the stars, or the beauty of a generous human action. The students knew viscerally that things are real, good, and true. They knew the world is filled with mysteries, beyond what our instruments can measure. Senior writes, “I retired to Kansas . . . to teach philosophia perennis by indirect means, forcing myself to rectify our students’ imaginations by teaching . . . poetry.”

The second goal was to bring students to the recognition that the Western cultural heritage could be a fountain from which to draw and not just a system to be dismantled. There again, this was accomplished by immersion in beauty. As Senior writes, “If you get someone into Plato or Newton or Shakespeare, he will see for himself why men have fought and died for western civilization.”

Delighting in reality, wondering at its mysteries, with a healthy imagination, a memory full of stories, songs, poems, experiences, one would be ready for life and eventually for more elevated, abstract studies.

As Christians, the professors also, most of all, hoped to help students come to Christ, the end of all things. But they did not push in that direction. They trusted in the intellect, but also in grace. They knew that their role was mainly to knock down obstacles and dispose. They simply kept to their leisurely meditation on what the great authors were saying, following each theme for itself and letting it eventually lead on its own in the direction of Christ, sometimes pointing forward a little. A good illustration of this realist pedagogy can be found in the counsel Senior gave teachers of high school natural science: “Don’t intrude religion. Just let the world be there. Let God teach as He intends in the language of nature which He Himself invented for the purpose. . . . Wrestling in the dirt under a clean sky in the flat light of an October sun, licked by the fiery tongues of maple leaves as they roll in them, the cool indifferent pines observing—well, you don’t have to say God made all this; it’s in the excitation of their blood.”

And about IHP readings he writes, “Grace attaches to nature. Students were converted as much by reading Plato as by Augustine. . . . When we taught the beauty of a poem or Homer’s Odyssey, we were not faking it, or trying to imbue the text with some phony Catholic gloss. The truth is always the truth, and if it is really true, it will lead you to the transcendent truth.”

The students once interested in things, looking at reality with normal human eyes, imagination, mind, and heart, and listening in delight and wonder to the great authors, would be motivated to seek the great truths and know where to find them. They could go forward from there on their own. And indeed they did.

Continuing Influence

Despite its popularity, a program so unapologetic in its embrace of traditional thought, values, and methods could not but find itself out of step with the priorities, agendas, and specializations of the modern research university. What’s more, in the eyes of administrators, an alarming number of students were converting to Catholicism. Some had even entered the monastic life! According to a summary report from an investigative committee, the program exhibited “a lack of tolerance for divergent points of view.” Through a series of bureaucratic manoeuvres and internal investigations, the program was slowly sidelined in the university curriculum and stripped of resources. Without the university’s support, and amid continuing hostility to its aims and purposes from administrators and professors, the program was shut down in 1979, not ten years after it had begun.

Given its short tenure, why did this program have such a decisive influence, a real culture shift for its students? The role of experience seems to be a key. The students experienced the beauty of great ideals of loyalty, love, fidelity, chivalry, the family, the community. They shifted course from rebellion to immersion in tradition. That foundational view would then inform the rest of their lives, not just in academic habits and careers, but in all their relations: their family life, the education of their children, their recreations, their habitats would flow out from those central certitudes. That holistic, experiential approach to reality creates a desire among those who come into contact with it to experience it for themselves, and to re-create it in their own ways and in their own communities.

The Spanish novelist and journalist Natalia Sanmartin Fenollera gives us an authentic painting of the program:

When I discovered what John Senior, Dennis Quinn and Frank Nelick did in [Kansas] I seemed to be contemplating a modern epic. The image of those three teachers in the auditorium of the campus, talking quietly among themselves about Homer and Plato, reciting poetry and telling stories, before an audience of astonished youngsters, made me think of three Greek heroes beginning an inspired fight against the modern world. It is a great story—how these students were rescued from a skeptical and sterile world and led through literature, poetry, and experience of reality to truth, goodness and beauty, with conversions, vocations, and a multitude of stories born in the Pearson program, and the silent adventure that goes from the campus of Lawrence to the Abbey of Fontgombault in France and the cloister of the monastery of Our Lady of the Annunciation of Clear Creek in Oklahoma—it has all the elements of a trip to Ithaca.

I was dazzled by the tremendous and beautiful footprints that Providence left impressed in Kansas; no noise, no large organizations, but by a sort of heart-to-heart contact. That is how God acts in the world.

Despite the particular context of the Integrated Humanities Program, the teachers’ fundamental views on education are universal and timeless. And as I have already observed, the deviations they fought are still with us. Students are more than ever cut off from reality by both ideology and technology, particularly social media. One cannot teach them unless one first turns the gaze of their eyes and heart toward reality. One must help them open to the great authors and point to the beauty of their teachings.

In 1995 Senior composed a little poem for the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the beginning of IHP. It conveys a sense of the mutual affection that existed among the students and teachers in a common gaze on the beautiful, the good, and the true. He says that springtime of discovery has proved itself to be genuine; its life has not withered:

This April neither fades nor feints

where we at Beauty’s Truth first kissed,

like the communion of all saints

whose lips touch in the Eucharist.